Robert S. Burrell

China’s gray zone conflict. Russian hybrid warfare. These terms have emerged to describe belligerent activities that standard US military operations struggle to address. Although these adversarial approaches remain central to today’s security environment, they are absent from the current joint doctrinal framework. Even the new joint doctrine note on strategic competition (JDN 1-22) fails to address hybrid warfare at all and there is only one mention of the gray zone. In fact, these two methods of conflict should remain front and center. Since the inception of joint doctrine, the United States has generally envisioned conflict in a linear fashion where peace and full-scale war occupy opposite sides of a continuum, with varying degrees of each in between. Doctrine’s evolution has made little change in this concept of a conflict continuum over time.

The 2022 US National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy made progress in detailing a more comprehensive approach to conflict. But much more can be done to incorporate both deterrence and competition, as well as irregular warfare, into operational design. As Eric Robinson detailed in an Irregular Warfare Initiative essay in 2020, there are four foundational ways of responding to belligerents: traditional warfare, deterrence, irregular warfare, and competition. If planners adopted this framework, they would have a full spectrum of conflict design that would help them to integrate ends, ways, and means into a coherent campaign plan. And they would also be better able to understand the activities of the United States’ most important competitors.

Understanding Conflict—From One Dimension to Two

The US joint force has attempted to define different forms of conflict for decades, but it has failed to move beyond a linear understanding. A competition continuum was introduced in a 2019 joint doctrine note, with cooperation on one end, adversarial competition below armed conflict in the middle, and war on the other end. This one-dimensional concept has been adopted by other doctrinal publications, such as Joint Publication 1 (the joint force’s capstone doctrine) and Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations. While this is the most recent conceptualization, for the past two decades doctrine has only slightly redefined categories between war and peace through minor revisions to descriptions and these changes have added little significance.

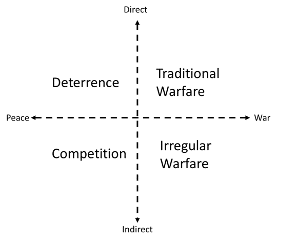

Connecting ways and means to strategic ends remains the essential task of strategy. Thus, adding a second means-based dimension to the existing continuum creates a full spectrum of conflict design, which dramatically improves our understanding. This second dimension—which serves as the y-axis in Figure 1—is similar to Herman Kahn’s work on escalation. While escalation of means varies with circumstances, means can generally be employed directly (and overtly), indirectly (including covertly and clandestinely), or somewhere in between. The full spectrum of conflict design creates a holistic framework that clarifies the relationship between means (the resources used in conflict) and ways (how those means are employed). Figure 1 illustrates the two-dimensional framework where the x-axis delineates the continuum between war and peace while the y-axis delineates the military means utilized. Together, these axes produce four ways: (a) traditional warfare, (b) deterrence, (c) irregular warfare, and (d) competition.

Figure 1: Full Spectrum of Conflict Design

Traditional warfare. This quadrant is characterized by the authorized use of conventional military force to defeat an adversary’s army. Traditional warfare also includes the implementation of a diplomatic treaty for the purposes of combined warfare. Conventional forces primarily dominate in this quadrant.

Deterrence. In this quadrant, a government prevents adversaries’ aggressive actions by threatening the use of traditional means. In addition, a peacetime coalition of treaty allies or the buildup of weapons of mass destruction can also deter aggression. The deterrence quadrant is characterized by nonviolent and low-intensity conflict between competitors—reinforced and backstopped by hard power.

Irregular Warfare. This quadrant identifies violent activities waged against an opponent through nontraditional and indirect methods, such as foreign internal defense and unconventional warfare (either conducted to support resilience and resistance). Special operations typically dominate in irregular warfare, and the means utilized are typically more population-centric tools than those utilized in the direct approach.

Competition. This quadrant is characterized by rivalry between nation-states or nonstate actors where the means utilized fall short of violence. This includes nonproliferation activities to deny competitors arms or equipment and sanctions imposed on persons, groups, and nations. It also includes persistent engagement by special operations forces to prepare an environment for violent irregular warfare if required. Finally, humanitarian assistance and stability activities occur in this space as they alleviate human security demands in unstable regions where rivals operate (like al-Qaeda and ISIS).

The Relationship Among Quadrants

These four ways directly relate to one another; they are not independent, and a nation can employ all of them simultaneously. For instance, deterrence fundamentally connects to traditional warfare because they both use the same means, from nuclear arsenals to aircraft carriers. In other words, weapons of mass destruction or conventional arms can be used for war or deterrence equally. One could also use traditional warfare and deterrence simultaneously, such as employing military forces while threatening the use of a nuclear response.

Likewise, competition and irregular warfare are directly related. Each can take deliberate actions in opposition to a state (or nonstate) competitor with indirect application of military means. The main distinction between the two is that irregular warfare simply uses more violence than competition. For instance, foreign internal defense might assist a partner force to ensure fair elections in a fragile state. This nonviolent activity occurs in the space of competition. However, that same military force can be used in a different way—to counter irregular threats with violence.

The five recognized components of irregular warfare (foreign internal defense, unconventional warfare, stabilization activities, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency) actually span the breadth of both competition and irregular warfare—a subject I published on in 2021. In fact, activities like stabilization primarily exist in nonviolent competition in most situations, rather than irregular warfare. The full spectrum of conflict design better allows the visualization of indirect use of military means in both competition and irregular warfare. Indirect uses of military power include (a) support to another regime’s resilience to protect its society from threats like subversion, lawlessness, and insurgency, and (b) supporting indigenous resistance against an adversary’s governance to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow the regime. Neither of these two methods (support to resilience or resistance) are constrained to violent means and concurrently exist in both the irregular warfare and competition quadrants. It is precisely for this reason that Joint Special Operations University has transitioned to the terms “support to resilience” and “support to resistance” as opposed to “irregular warfare.” These terms acknowledge the interdisciplinary nature of conflict in these quadrants, which serves to offer more comprehensive solutions that include diplomatic, informational, military, and economic aspects.

Military planners can more holistically address irregular threats by including both competition and irregular warfare as separate but related ways of dealing with violent and nonviolent threats. With this framework planners and operators will be prepared for nonviolent activities to evolve into irregular warfare, or for violent activities to revert to competition. Operation Restore Hope in Somalia is a good example of military force initially utilized for peaceful humanitarian assistance quickly evolving to employ violent means to establish rule of law. My 2021 article further illustrates such shifts.

In short, the full spectrum of conflict design framework should not be used to compartmentalize any nation’s activities into a single quadrant or type of military means as conflict rarely relies exclusively on one type of means. Figure 1 uses dotted lines to indicate that conflict might (and likely will) include activities in more than one space. As further explained below, activities that span multiple ways result in hybrid warfare or gray zone competition.

Clarifying Gray Zone and Hybrid Warfare

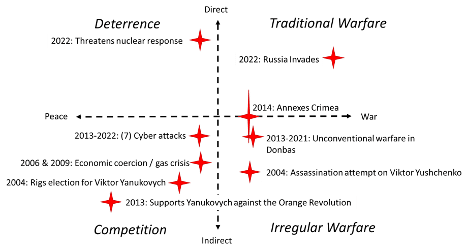

By employing multiple means illustrated in the full spectrum of conflict design framework, nations may specifically operate near the axes where activities are blurred to intentionally complicate an adversary’s response. Fortunately, the framework allows scholars and practitioners to visually identify gray zone conflict and hybrid warfare as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Identifying Gray Zone and Hybrid Warfare

In the figure, gray zone conflict occurs along the y-axis, because the gray zone blurs the line between war and peace. For example, the Chinese Communist Party tends to operate aggressively in the gray zone, as this gives it freedom of action without consequences. In the South China Sea, it often employs a maritime militia, instead of its navy, to enforce recognition of its territorial claims to disguise its intentions where actions are not clearly identified as warlike or peaceful.

Hybrid warfare occurs along the x-axis by purposefully implementing both direct and indirect means. In 2014, Russia invaded Crimea by sponsoring proxies and inserting Russian operatives without uniforms. At the same time Russia used its air force and navy to enforce air and maritime exclusion zones. Further, Russia used economic pressure and nuclear threats to ensure noninterference from NATO. Russia also established and maintained its narrative through propaganda with domestic and international audiences to justify its aggression.

Applying the Full Spectrum of Conflict Framework

One application for the full spectrum of conflict design is to map out major events in a struggle, to better appreciate the ways and means utilized and to identify the inherent nature of the conflict or the strategies of the participants. Applied to Ukraine, as an example, the product is a graph illustrating major Russian actions taken against Ukraine from 2003 through 2022.

Figure 3: Full Spectrum of Conflict Design, Russian Aggression, 2004-2022

In general, the graph demonstrates that Russian aggression has been escalatory in terms of military means over time. Russia began its campaign with influence, cyber, and economic coercion (2003–2013), subsequently transitioned to irregular warfare supported by traditional warfare (2013–2021), and finally transitioned to traditional warfare (2022) while simultaneously making threats of a nuclear response for the purposes of deterrence (2022). Russia’s activities occupy all four quadrants, generally employing a hybrid warfare approach (particularly in 2014) and leveraging multiple ways and means in achieving national objectives.

The Way Ahead

Today, both the State Department and the Department of Defense often identify belligerent aggression that does not fit neatly along a linear conflict continuum, resulting in a bewildered and delayed response. Hybrid warfare and gray zone aggression will likely continue to be the foremost methods for employing ways and means in twenty-first-century conflict. As such, a full spectrum of conflict design framework better allows for collaboration within the US government in matters of national security. As Philip Kapusta argued in 2015, understanding the gray zone can “enable early application of U.S. instruments of power . . . by shaping the arc of change closer to its origins.” Utilizing the full spectrum of conflict design better identifies origins in the gray zone.

Employing means in multiple ways creates the advantages of hybrid warfare and gray zone competition, but current joint doctrine and its linear approach to conflict limits the US military’s ability to detect or employ these methodologies. Joint doctrine can broaden conflict analysis by adopting a framework that integrates the distinct ways of (a) traditional warfare, (b) deterrence, (c) irregular warfare, and (d) competition. The full spectrum of conflict design allows for increased understanding of the linkages and relationships between direct and indirect means across the continuum of peace and war. This framework provides a fuller picture of multiple efforts oriented toward the same desired outcome. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a prime example of how the use of the full spectrum of conflict design can be applied to better illustrate and articulate aspects of conflict in one graph.

Military planners can adopt the full spectrum of conflict design to synchronize activities throughout engagement and contingency plans, as well as major operations and campaigns. This simple framework allows practitioners to analyze and integrate multiple ways and means into one planning frame, as well as to synchronize resources and actions to achieve strategic ends. Finally, the full spectrum of conflict design can help scholars, planners, and theorists graphically appreciate, and potentially anticipate, the strategies of opponents.

No comments:

Post a Comment