Neil Shearing

There is now broad agreement among economists and commentators that the world has reached peak globalization, but there is little consensus about what comes next. One view is that we are entering a period of ‘deglobalization’, in which global trade volumes decline and cross-border capital flows recede. An alternative and more likely outcome is that the global economy starts to splinter into competing blocs.

This would result in an altogether more volatile macroeconomic and market environment which would pose a formidable challenge to some countries and companies operating in vulnerable sectors. But this process needn’t involve any significant shrinkage of international flows of goods, services and capital, nor a broad reversal of other gains of globalization.

Whereas the period of globalization was driven by governments and companies working in unison, fracturing is being driven by governments alone.

This most recent era of globalization was underpinned by a belief that economic integration would lead to China and the former Eastern Bloc countries becoming what former World Bank Chief Robert Zoellick termed ‘responsible stakeholders’ within the global system.

But China has instead emerged as a strategic rival to the US. This strategic rivalry is already forcing others to pick sides as the world splinters into two blocs: one that aligns primarily with the US and another that aligns primarily with China.

Increasingly, policy choices within these blocs will be shaped by geopolitical considerations. This process can be thought of as ‘global fracturing’. Whereas the period of globalization was driven by governments and companies working in unison, fracturing is being driven by governments alone.

The effects of fracturing

Viewed this way, ‘deglobalization’ is by no means inevitable. There are few compelling geopolitical reasons why the US or Europe should stop importing the majority of consumer goods from China. Roll the clock forward ten years and it is likely that the West will still be buying toys and furniture from China. Instead, fracturing between the blocs will take place along fault lines that are geopolitically important.

In some aspects, the effects of fracturing will be profound. But in other areas, warnings of a seismic reordering of the global economy and financial system will prove wide of the mark.

For example, the politically-driven nature of fracturing will have a significant impact on the operating environment for US and European firms in those sectors that are most exposed to restrictions on trade, such as technology and pharmaceuticals. And all firms and investors will be operating in a different environment in which geopolitical considerations play a greater role in decisions over the allocation of resources.

In cases where production does shift location, it is likely to be to other low-cost centres that align more clearly with the US. There will be no great ‘reshoring’ of manufacturing jobs.

But where production is moved to alternative locations, this is likely to only involve the manufacture of goods that are deemed to be strategically significant. This may include those with substantial technological and/or intellectual property components: think iPhones, pharmaceuticals, or high-end engineering products.

What’s more, in cases where production does shift location, it is likely to be to other low-cost centres that align more clearly with the US. There will be no great ‘reshoring’ of manufacturing jobs.

Within this process, trade linkages will be reordered, rather than severed. This will result in trade’s share of global GDP flatlining in the coming years, rather than shrinking outright, as is being forecast under many attempts to quantify deglobalization’s potential impact.

Finances of global fracturing

There will be a substantial financial component to global fracturing, but once again the implications are likely to be more nuanced than the current debate suggests. Cross-border financial links are likely to grow more slowly, and the overall stock of cross-border claims will plateau relative to global GDP. But whereas the first era of globalization in the 1870s was followed by a broad retreat in global capital flows during the interwar years, the same is unlikely to happen today.

Beijing will increasingly push its partners to settle trade in renminbi but this is unlikely to seriously challenge the dollar’s position.

Similarly, while financial fracturing will fuel growing speculation about the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, reports of its impending demise are exaggerated. Beijing will increasingly push its partners to settle trade in renminbi but three factors suggest that this is unlikely to seriously challenge the dollar’s position.

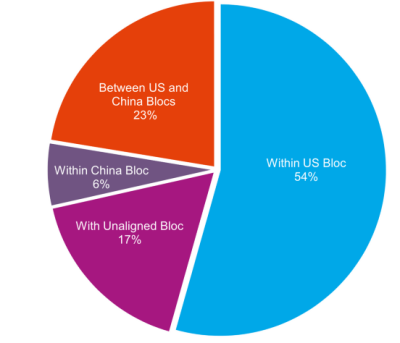

First, while trade between China and its partners is growing, it still accounts for only six per cent of global trade. Most trade still happens between US-aligned countries, and will continue to be denominated in US dollars (see chart).

Second, China runs a large current account surplus, which will make it harder for the renminbi to supplant the dollar. High demand for reserve assets means that reserve countries tend to run current account deficits.

—

—Share of global goods and services trade (%) Source: Capital Economics

Finally, the dollar still has several things working in its favour. For a currency to be widely used as an international medium of exchange, it must be readily and cheaply available around the world. In turn, that depends on foreigners being willing to hold it in large volumes: in other words, it must function as a store of value.

Our flagship newsletter provides a weekly round-up of content, plus receive the latest on events and how to connect with the institute.

Dollar not only currency cont.

The dollar is not the only currency that could perform this role. But any alternative would need to share similar attributes: it would have to be backed by strong and stable institutions and issued by a central bank that operated an open capital account.

What’s more, any currency that had these characteristics would have to overcome the strong network effects that underpin the dollar’s global dominance. All of this is likely to work against the internationalization of the renminbi on a scale that threatens the dollar’s position.

The world economy is fracturing rather than deglobalizing: global flows of goods, services and capital won’t shrink in aggregate and in some areas integration will deepen. But, with geopolitics back in the driving seat, it will be a more uncertain economic environment as trading relations adjust to a bifurcated world economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment