Peter Layton

High-flying espionage went out of fashion in the 1960s, but the most recent sky crisis has reignited tensions.

Bizarrely, the Chinese have sent a high-flying spy balloon deep into the American heartland. The logic is that such balloons fly more than 22.2 kilometres above the surface. Under international law, a nation’s territorial seas and the airspace above it extend to 12 nautical miles (22.2km). Accordingly, China’s high-altitude balloons are arguably flying in international airspace. It’s plausibly legal but also highlights the fact that if a balloon overflies a country below 22.2 kilometres altitude, that country’s sovereignty has been infringed and the craft can be legally shot down. Both happened in this case over the weekend.

High-flying balloons are very common. Some 800 small weather balloons are launched daily and fly up to 40 kilometres altitude. The United States launched hundreds of spy balloons over the Soviet Union in the 1950s. The Soviets grumbled that these were “incompatible with normal relations between states”, and they had a point. Some 90 per cent failed, and then came the development of spy satellites that were more capable, reliable and less provocative. Using balloons for long-range spy missions went out of fashion.

China describes its balloon detected over the U.S. mainland last week as an airship with a limited self-steering capability. It was very large, with its instrumentation payload of surveillance equipment approximating the size of three buses, and solar panels some tens of metres in length. Unalerted observers on the ground could see it clearly in the sky; it was a second moon.

While space-based systems are at least as good in intelligence collection, they have very predictable orbital dynamics, giving adequate warning time for activities on the ground to be concealed. Balloons, though, can take advantage of winds and ascend or descend to a limited degree. Such controllability means they can loiter to some extent, unlike satellites.

Balloons go where the east-west high-altitude winds push them. Last week’s Chinese spy balloon flew across the Pacific through the western Aleutians, into British Columbia and across Montana into Missouri, finishing up being shot down 10 kilometres off the South Carolina coast – by coincidence, a course taking it across several sensitive U.S. strategic nuclear deterrent sites. The balloon’s role was most likely signals intelligence collection concerning communication systems and radars. The balloon probably transmitted the information collected back to China via a space-based communications relay satellite in real time.

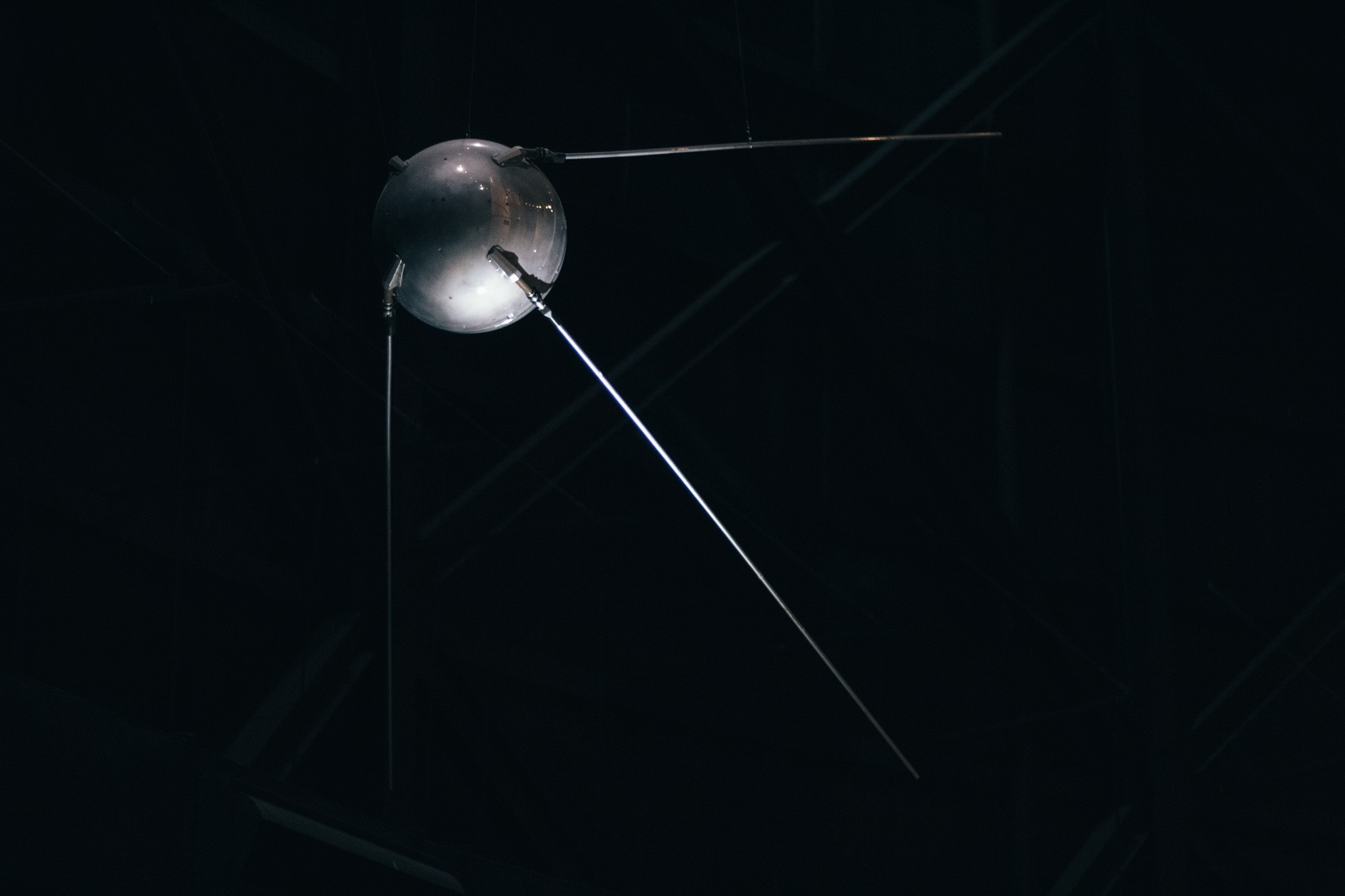

In many respects, China's spy balloon represents a Sputnik moment that dramatises to the American public the China challenge (Sean Foster/Unsplash)

That is the technical side, but there is more to be considered.

First, the balloon fits grey zone activity parameters – being well planned, purposeful and avoiding violence. Given this, it sets a new normal. It suggests that like earlier grey zone activities in India, the South China Sea, East China Sea, Taiwan and South Korea, this will happen again. Indeed, this is not the first time, simply the first that has been publicly acknowledged. Other Chinese balloons have flown over Taiwan, near Guam and Hawaii, across Columbia and Venezuela and apparently over the continental United States during the Trump administration.

Second, in many respects this is a Sputnik moment that dramatises to the American public the China challenge. If office workers and households across the American heartland can look out their windows and see a Chinese spy balloon the size of a second moon cruising past, this creates a powerful strategic narrative. China deliberately acted to inflame America’s China hawks while simultaneously trying to embarrass the Biden administration. Instead of proactively placating the administration, China employed obfuscation and denial. Worse, if China really didn’t mean to inflame tensions, it suggests Beijing’s crisis management techniques are poor and very worrying for a major nuclear power.

Third, this might be an opportune moment for a revamped open skies initiative. Agreed to post-Cold War, there were 34 members before the Open Skies treaty fell apart due to Russian violations. Open Skies participants made their territory accessible to overflights by unarmed observation aircraft. The nations could restrict flights for safety reasons, but couldn’t obstruct or forbid flights, including over military installations. If China thinks it needs overflights, maybe now is the time to publicly push countries towards a modern open skies treaty. China has already called for setting guardrails.

Fourth, China’s chutzpah is always impressive. Having created a major diplomatic incident, they now accuse the United States of recklessly shooting down a globe-trotting Chinese government-owned airship that was operated covertly and flew inside U.S. airspace for days. This is an airship that flew over Billings, Montana at 18.2 kilometres (60,000 feet), well below the 22.2-kilometre national airspace limit. China knowingly infringed U.S. sovereignty as they controlled the sensors and steered the airship.

Last, the great hopes that China was moving away from wolf-warrior diplomacy to become a more responsible member of the international community seem dashed. China appears to be its own worst enemy. Recent American efforts to isolate China in areas such as microchip imports and production are starting to seem prescient. And worryingly, an escalating trend seems apparent with the occurrence of other recent Chinese grey zone incidents. Looking forward, China seems to be “pushing the envelope” towards an alternative future where it is increasingly bellicose, and increasingly willing to use uncrewed systems aggressively.

There’s more to come on this story. It’s not just all hot air.

No comments:

Post a Comment