Matt Fratus

Military service draws recruits from all walks of life — from inner-city kids and country folks to Ivy Leaguers and corporate dropouts. Included in this diverse group are people with the potential to become great authors. And sometimes those people leave the military with enough story material to fill a book or two — that, or simply the discipline and drive necessary to pursue a serious writing career.

Of course, not every author who served chooses to write about the military. Likewise, not every author who writes compellingly about the military served themselves. Some of America’s greatest novelists fall under this category. Both Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck tried and failed to join the military, yet each drew from their experiences as civilians in conflict zones to produce some of the most captivating war novels in the genre.

All of this is to say that there is no exact definition of a “military writer.” Nevertheless, we have compiled a list of 10 American authors to whom the term can be truthfully applied. There are many more writers who belong on this list, but for the sake of brevity we whittled it down to our all-time favorites.

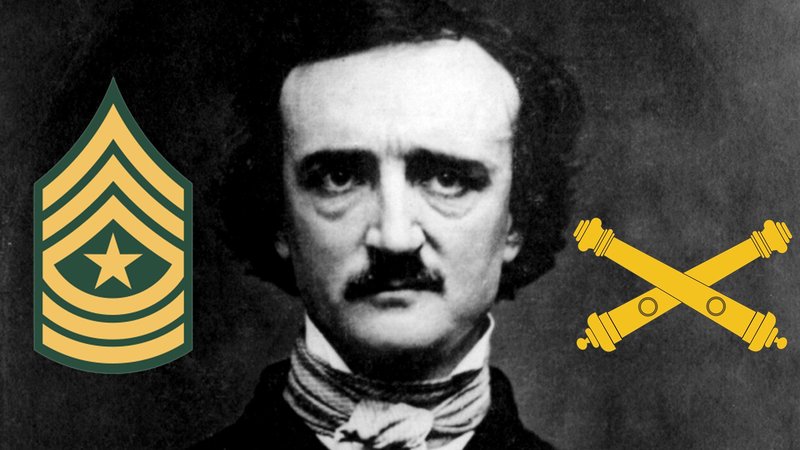

Edgar Allan Poe

Before Edgar Allan Poe was a famous poet, he was a sergeant major in the US Army. Composite by Coffee or Die.

Edgar Allan Poe enlisted in the US Army in 1827. He gave his recruiter a false name — Edgar A. Perry — and claimed he was 22 years old even though he was only 18 in order to meet the minimum age to enlist at the time. Poe served first as an artilleryman in Boston Harbor and then later as an artificer, i.e., someone who prepared and handled explosives. Within two years of joining the Army, he was promoted to sergeant major, the highest rank attainable by an enlisted soldier.

Despite his big promotion, Poe soon decided that he’d had enough of soldiering. So he made a deal with his commanding officer to enroll at the United States Military Academy in exchange for an early discharge. Once at West Point, however, Poe quickly realized that he wasn’t cut out for the life of a cadet, either. Over the next several months, he worked hard to get kicked out of the prestigious academy, accruing 44 offenses and 106 demerits during his first semester.

Ultimately, Poe’s bad behavior paid off, and he was released back into civilian society before completing his plebe year.

In 1831, the same year he left the academy, Poe used donations he collected from 131 fellow West Point cadets to publish Poems. His donors expected a book of witty poems poking fun at their West Point instructors. But instead of the humorous poetry Poe used to recite for the entertainment of his classmates, he used the money to republish old material. The only mention of West Point appears in the book’s dedication: “To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated.” His classmates were not pleased. Apparently, some even threw their copies of Poems into the Hudson.

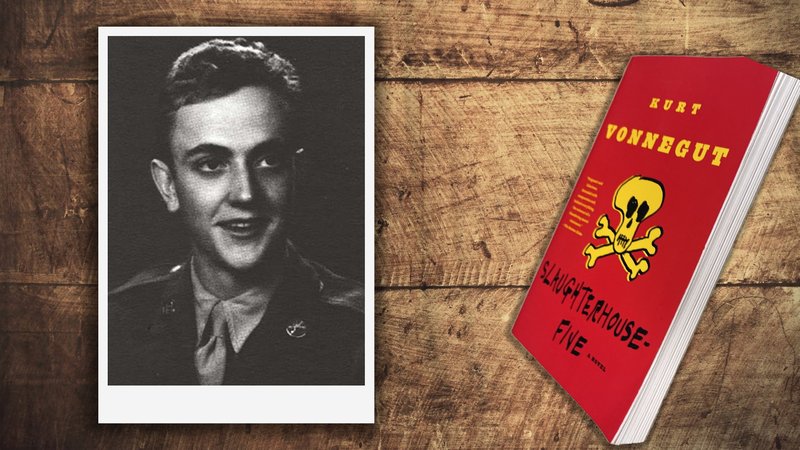

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut wrote about his experiences in Slaughterhouse-Five. Composite by Coffee or Die.

From January 1943 to June 1945, Pfc. Kurt Vonnegut served as an intelligence scout with the 423rd Infantry Regiment of the US Army’s 106th Infantry Division. The regiment was sent to Europe and ended up in Nazi Germany along the Siegfried line, a defensive barrier of bunkers, tunnels, and tank traps. In December 1944, Vonnegut and some 6,697 other soldiers from his division were captured by the Germans while fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

Troops taken prisoner of war in Europe were often transported to detention camps by train. To reduce the chances of the train being targeted by Allied planes, the Germans would adorn them with Red Cross symbols. However, this was not always the case.

There were no Red Cross symbols on the train that carried Vonnegut and his comrades through Germany toward the Stalag IV-B POW camp in Mühlberg. On Christmas Eve, the train was strafed and bombed by British aircraft. The airstrike killed about 150 men. After the dust settled, Vonnegut and the other survivors, still crammed into the train’s cold, unventilated boxcars, continued their journey and arrived at Stalag IV-B on New Year’s Day 1945.

Vonnegut and approximately 150 others were soon transferred to a work camp in Dresden. They were housed in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof 5 (in English: Slaughterhouse 5). For months, the 22-year-old future novelist endured forced labor, working long hours in a German malt-syrup factory. Then, in February, the Allies firebombed Dresden, killing an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people. The firestorm spared Vonnegut as he hunkered down in an underground meat locker. When it was finally over, Vonnegut and other POWs were tasked with carrying the corpses of men, women, and children to massive funeral pyres around the city.

Dresden was liberated from the Nazis by the Soviet Red Army in May 1945. Two and a half decades later, Vonnegut published his famous anti-war novel, Slaughterhouse-Five. The novel follows the protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, a chaplain’s assistant who, like Vonnegut, gets captured by the Germans, is interned in a POW camp, and witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

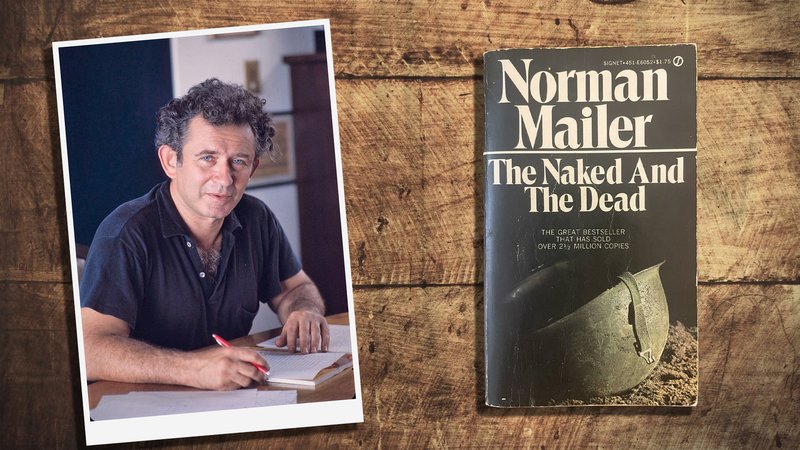

Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer served in the Pacific theater and later wrote about his experiences in his novel, The Naked and the Dead. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Norman Mailer was 21 years old, newly married, and had just earned a degree in engineering from Harvard when he received his draft notice in 1944. He attended basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. With a college degree from an Ivy League school, Mailer could have easily attained an officer’s commission. Yet he chose to serve as an enlisted soldier, believing it would increase his chances of seeing action on the front lines. He underwent training in the field of artillery fire control and then received orders to deploy to the Philippines with the San Antonio-based 112th Armored Cavalry Regiment.

In early January 1945, Gen. Douglas MacArthur landed his massive invasion force on the fortified beaches of Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands. Mailer was close by, waiting on board a troop ship as the assault got underway. He eventually joined his company inland and worked as a typist for the intelligence and operations section of regimental headquarters.

Eager to get closer to the action, he got himself transferred to a platoon responsible for repairing and laying communication wires. The assignment put Mailer in the field working alongside small units in the villages, rice paddies, and hills of Luzon. Still not satisfied, he requested another transfer and was sent to the company’s reconnaissance platoon. As a recon soldier, he carried a rifle and conducted numerous patrols. However, according to Mailer, he only saw “modest bits of action.”

Immediately after the war in the Pacific ended, Mailer was assigned to duty in occupied Japan. He spent the remainder of his military service in Tateyama and Chōshi working as an Army cook.

In 1948, Mailer published his bestselling novel, The Naked and the Dead. The book is loosely based on Mailer’s experiences on one particular reconnaissance patrol. Mailer spoke about the process of fictionalizing that experience in a 2004 interview with the Academy of Achievement. “I chose to take this small patrol, which seemed very dangerous in the beginning to us, but ended in fiasco,” he said, “and that patrol took several days in The Naked and the Dead and got much exaggerated.”

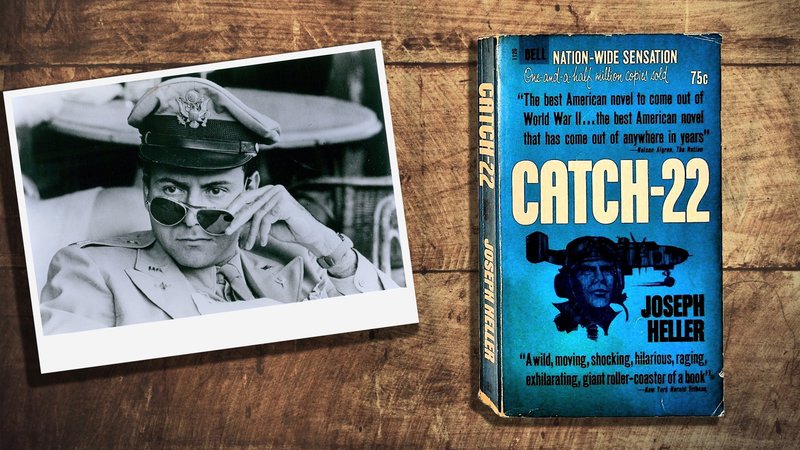

Joseph Heller

Alan Arkin, left, starred as Capt. John Yossarian in the 1970 movie adaptation of Joseph Heller's book, Catch-22. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Joseph Heller enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in 1942 at the age of 19. Two years later, he deployed to Europe with the 488th Bombardment Squadron, 340th Bomb Group, 12th Air Force. He served as a bombardier aboard a B-25 — one of the most dangerous jobs in the military at the time — and managed to return home in one piece.

By the time his tour was finally over, Heller had flown approximately 60 missions over France and Italy. In an interview with Playboy magazine in 1992, Heller spoke about his homecoming. “I felt like a hero,” he said. “People think [it’s] quite remarkable that I was in combat in an airplane and I flew sixty missions even though I tell them that the missions were largely milk runs.”

Heller spent much of the 1950s writing his first novel, Catch-22. The book was published in 1961 and became an instant hit. Generally considered an anti-war novel, Catch-22 focuses on the crazy and often hilarious escapades of Capt. John Yossarian, a US Army Air Corps B-25 bombardier stationed near Italy, who spends his tour doing everything he can to avoid being killed in action.

It’s natural to assume that Yossarian is a caricature of Heller himself. However, according to the author, that is not the case. In a letter he penned to a college professor in the 1970s, Heller explained that, unlike his famously cynical protagonist, he actually liked being a bombardier. “In truth,” he wrote, “I enjoyed it and so did just about everyone else I served with, in training and even in combat.”

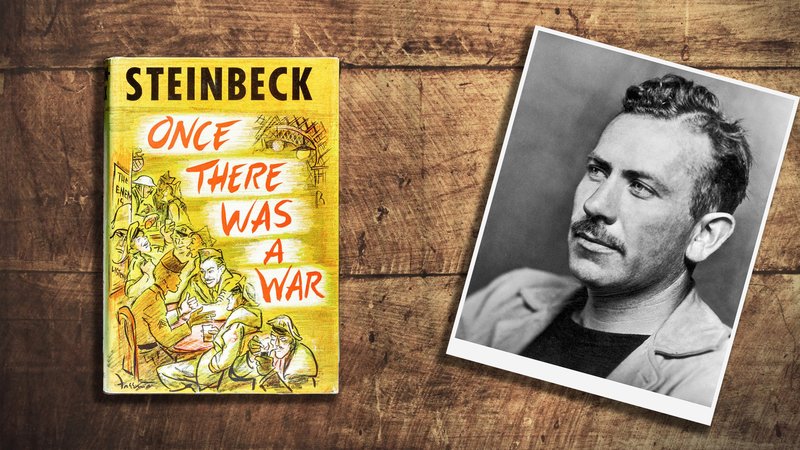

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck didn’t serve in the US military, but he did embed with a shadowy Naval Special Warfare unit during World War II. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

When the US entered WWII, John Steinbeck had just received a Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Grapes of Wrath. He was already a major celebrity and, according to the draft board, too old to serve his country in war. But as droves of Americans half his age were being marched off to fight and die on the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific, the great novelist refused to hang back and do nothing. He was determined to support the cause.

Steinbeck’s first contributions to the war effort were two works of propaganda — a novel titled The Moon Is Down, which he wrote at the behest of the Office of Strategic Services, and another novel, Bombs Away, which was commissioned by the Office of War Information. Then, in 1943, at the age of 41, he took a job as a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune.

While most military reporters focused on the war as it was being waged at the strategic level, Steinbeck was determined to capture the gritty experiences of soldiers on the ground. He eventually attached himself to a shadowy naval special warfare unit known as the “Beach Jumpers.” The Beach Jumpers utilized fast, agile boats to conduct false amphibious invasions on Axis-held beachheads, the goal being to confuse the enemy and draw their attention away from the places where Allied forces actually intended to land.

Steinbeck embedded with the Beach Jumpers in Italy. He shadowed their leader, a Hollywood actor turned Navy commando named Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Like Steinbeck, Fairbanks had put his celebrity life on pause to serve overseas. Having removed the insignia that identified himself as a journalist, Steinbeck accompanied Fairbanks and his men on missions and even carried a Thompson submachine gun. (It is unknown whether he ever fired the weapon.) Steinbeck’s 1958 collection, Once There Was a War, included compelling dispatches about these exploits. However, Steinbeck didn’t mention the Beach Jumpers or Fairbanks by name due to the wartime censorship and secrecy of their operations.

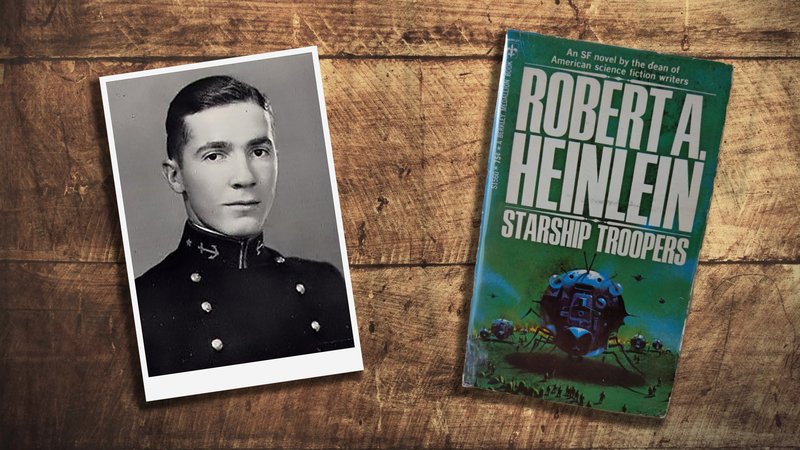

Robert A. Heinlein

Robert A. Heinlein served with the US Navy. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Robert Heinlein graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1929 with a degree in naval engineering. The new ensign joined the crew of the USS Lexington aircraft carrier and was responsible for operating radio communications equipment and coordinating with planes. Heinlein was later assigned to the USS Roper Wickes-class destroyer. He achieved the rank of lieutenant, but in 1934, at the age of 27, he was medically retired after contracting pulmonary tuberculosis.

In 1939, a popular science-fiction magazine called Thrilling Wonder Stories encouraged new or unpublished writers to submit their stories. Heinlein was inspired to write “Life-Line,” about a professor who builds a machine that can predict the life expectancy of people. It was published in Astounding Science Fiction, which paid a higher rate.

After the attacks against Pearl Harbor, Heinlein attempted to reenlist in the Navy during World War II. He was denied. So, instead, he took a job as a civilian engineer at the Naval Air Experiment Center in Philadelphia.

In 1959, Heinlein authored the sci-fi classic Starship Troopers, which follows a young soldier’s journey from recruit to officer during an interstellar war fought between humans and arachnid aliens. The story was later loosely adapted into a feature film that became a cult classic.

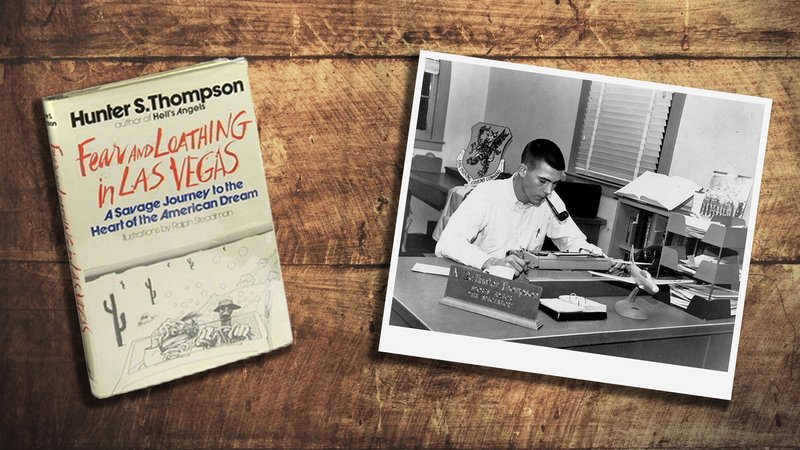

Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson, right, served in the US Air Force in the 1950s. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

At the age of 17, Hunter S. Thompson was arrested and charged with accessory to armed robbery. He spent 60 days in Jefferson County jail in Louisville, Kentucky. Then a judge gave him an ultimatum: He could either go to prison or join the military. Thompson chose the latter and enlisted in the US Air Force in 1955.

Thompson applied to become a pilot, but his application was denied. He took a job working with electronics at Eglin Air Force base in Fort Walton Beach, Florida.

In 1956, Thompson came across a job posting for a position as a sportswriter at the military newsletter Command Courier. The future gonzo journalist lied about his credentials to get the job. As a sportswriter, he drew scorn from his superiors with his heavy use of innuendo and exaggerated writing style. Before he was honorably discharged in 1957, Thompson penned a fake press release about “one of the most savage and unnatural airmen” any senior leader had ever seen. The kicker: The subject of the story was Thompson himself.

After the military, Thompson went on to have a monumental journalism career and wrote several famous novels, including the bestseller, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

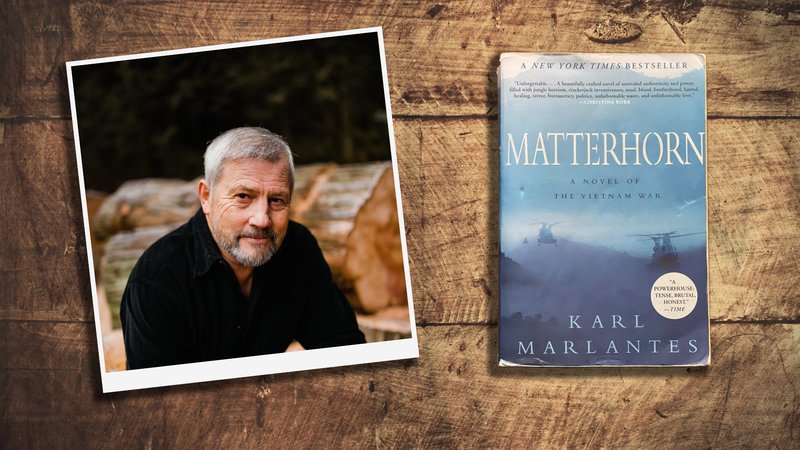

Karl Marlantes

Karl Marlantes received the Navy Cross while serving as a Marine in the Vietnam War. He later wrote about his experiences in his books. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Karl Marlantes joined the US Marine Corps at 19 and served as an infantry officer.

In October 1968, Lt. Marlantes went to Vietnam for a yearlong tour with 1st Battalion, 4th Marines. He earned a Navy Cross — the second-highest award for valor that a Marine can receive — for leading two platoons of Marines in an assault on a hilltop bunker complex. During his tour, he also worked as an aerial observer. As a result of his actions while serving in that capacity, he was awarded a Bronze Star, two Navy Commendation Medals with “V” device, two Purple Hearts, and 10 Air Medals.

Marlantes left the Corps in 1970. Many years later, he published his first book, Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War, a semi-autobiographical novel about a young Marine lieutenant leading a rifle platoon in the highlands of Vietnam. Marlantes also authored a memoir, titled What It Is Like to Go to War.

Tim O’Brien

Tim O’Brien served in the US Army during the Vietnam War and wrote about his experiences in numerous essays and books, including The Things They Carried. Photo by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Tim O’Brien was drafted into the US Army in 1968 at age 22. He would later say that the training he received before going to Vietnam didn’t adequately prepare him for guerrilla warfare. Sgt. O’Brien served as an infantryman with 3rd Platoon, Company A, 5th Battalion, 46th Infantry Regiment, 198th Infantry Brigade, in Quang Ngai province, Vietnam, from 1969 to 1970. Early on in his tour, O’Brien and his company were ambushed near a small hamlet dubbed “Pinkville.” At one point during the firefight, a grenade landed between O’Brien and another American soldier. The blast hurled shrapnel into O’Brien’s legs and backside.

After Vietnam, O’Brien wrote about his experiences in numerous books and essays, including in his award-winning novel, The Things They Carried.

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway may have not served in the military, but he tried. Still, he wrote some of the best novels about the subject in the 20th century. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Technically, Ernest Hemingway never served in the military. He tried to enlist in the US Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, but was rejected by all three because of his bad eyesight. Then, at the age of 19, he volunteered to serve in Italy as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross.

In June 1918, Hemingway was struck by an Austrian mortar while handing out chocolate and cigarettes to Italian troops in the trenches. Although dazed and wounded by shrapnel, he helped carry an Italian soldier out of danger and took a bullet just below the right knee in the process. Years later, he drew on his experiences in World War I to write his acclaimed novel, A Farewell to Arms.

In 1922, Hemingway worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, and traveled to Turkey to cover the Greco-Turkish War. He published Three Stories and Ten Poems the following year. In the 1930s, Hemingway covered the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance. His experiences in Spain also provided the basis for his 1940 novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

No comments:

Post a Comment