Mordechai Chaziza

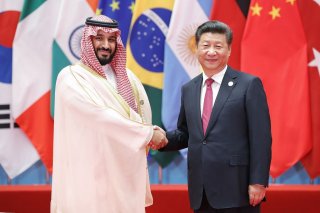

During his visit to Saudi Arabia in early December, Chinese president Xi Jinping attended the inaugural China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit. The summit focused on improving China-GCC relations and forming security ties between the parties. In his speech at the summit, Xi called on the two sides to be “natural partners” for cooperation and proposed five major areas for cooperation: energy, finance and investment, innovation and new technologies, aerospace, and language and cultures. Nevertheless, a glance at the engagement shows where the focal point of each partnership lies: energy, technology, and trade. For the Gulf monarchies, trade ties with China will diversify their economies away from the oil that provides most of their national income. More importantly, in the context of global competition, the summit delivered no concrete commitments to deepen the China-GCC strategic partnership, and nothing new was announced in the realm of security.

The China-GCC Strategic Partnership

In the Gulf—where the United States has been the predominant external actor for decades—China has sought to forge close political ties with emerging powers to secure access to vital energy resources, expand its commercial reach, and enhance its strategic influence. While China believes U.S. hegemony in the Gulf is in decline, its approach to achieving great power status and influence has been cautious and hesitant. Fomenting instability does not benefit China, which has neither the will nor the capacity to fill the regional security role held by the United States. Instead, China has developed strategic partnerships with key GCC countries whose support can bolster its great power status and allow it to project its influence into new arenas.

This suggests that China is determined to avoid confrontation with the United States and does not want to be sucked into the region’s multiple conflicts. Beijing prefers to take a position of non-interference, allowing it to remain neutral in most inter-regional disputes and take advantage of strategic and economic opportunities. As a result, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects in the Gulf are primarily a means to strengthen Beijing’s great power status in the region. This non-interference policy is essential for guaranteeing the success of the BRI framework by maintaining neutrality and alienating no one. At the same time, the Gulf monarchies see China as an exemplary trading partner that does not interfere in domestic affairs and as a great power with significant political influence in the international arena.

China carries out its relations with the Gulf monarchies through partnership diplomacy rather than alliance politics (these relationships are not alliances, as Beijing has typically shied away from forming alliances). China has signed strategic partnership agreements with the GCC states detailing significant economic investment and trade within the BRI framework, including comprehensive strategic partnerships with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, two of the region’s most powerful and resource-rich countries, and strategic partnerships with Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar. It is important to note that China’s partnership diplomacy in the Gulf hinges on deepening bilateral relations and partnerships with existing U.S. allies to expand its influence and access to energy while simultaneously avoiding confrontation with Washington.

Nevertheless, the relative decline of U.S. hegemony and influence in the Persian Gulf, which is taking place alongside China’s growing role, affects the region’s balance of power. While maintaining their strategic partnerships with the United States, some GCC states—Saudi Arabia and the UAE, for instance—are also seeking to hedge against threats and the rapidly shifting balance of power by establishing ties with other powers. This hedging policy aims to use China as an additional source of political, economic, and even military support, as well as to use ties with Beijing to pressure Washington to adjust its policy.

Great Power Competition

Great power competition between the United States and China has reached new heights, becoming the most important dynamic on the world stage, and shaping the international order as it unfolds. Between an increasingly alarmed Washington and an emergent, assertive Beijing, the GCC states find themselves in a choice between their major strategic ally and an important economic partner. Nevertheless, the China-GCC partnership’s future will not be determined by what the great powers desire to gain from the Gulf monarchies but by what the Gulf states expect to earn from the great power rivalry. This expectation highlights the strange, complex China-GCC relationship.

Although the China-GCC summit emphasized intra-GCC unity, the Gulf states do not have a unified, coherent vision for a regional approach to great power rivalry. The Gulf monarchies share a common skepticism of Washington’s future commitment to the region, but their attitudes vis-à-vis China and great power rivalry differ significantly. These varying views can be divided into three groups. The first group, the “hedging states,” includes Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Both are openly hedging against Washington’s withdrawal from the Gulf. Thus, they have incorporated a comprehensive strategic partnership element into their engagement with China. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are actively looking to diversify their supply of weapons, with China now considered a top alternative for essential military equipment that the United States refuses to sell to them.

The second group is the “balancing states,” Qatar and Oman. Both cultivated closer ties with China by opening up their national infrastructure and digital networks to Chinese investment. However, they have been more cautious regarding great power rivalry and maintaining their close military ties with Washington. Qatar deepened its relationship with the U.S. military—recently upgraded to the status of a major non-NATO ally—through its vital role in the evacuation from Afghanistan in 2021. Oman has been careful not to buy Chinese military equipment—unlike Qatar, which purchased ballistic missiles from Beijing—and signed a new strategic framework agreement with Washington in 2019 that gave the U.S. Navy access to the Port of Duqm.

The third group is the “cautious states,” including Kuwait and Bahrain. Both nations have opened up their countries to Chinese investment and construction projects but refrained from turning commercial ties into strategic ties. Kuwait and Bahrain have the most limited military capabilities among the GCC states and see U.S. protection as vital for their security. Indeed, approximately 13,500 U.S. forces are based in Kuwait; only Germany, Japan, and South Korea host more U.S. forces. Bahrain hosts the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet and U.S. Naval Forces Central Command and participates in U.S.-led military coalitions. Both states have far more to lose from engagement with China than their neighbors.

While great power competition has revealed the various strategies pursued by each of the GCC states regarding China, their different approaches make it difficult to predict the future of GCC-China ties.

Amid great power competition, the war in Ukraine, and the struggle for technological-economic dominance, the GCC states have been forced to prudently navigate between the United States, their great strategic ally, and China, their significant economic partner. The various strategies pursued by each state regarding the U.S.-China rivalry will eventually test the region’s security and stability, possibly dividing the GCC. The Gulf states must develop a diplomatic framework to address their foreign policy differences and prevent the region from becoming an arena for the struggle between Washington and Beijing. If the Gulf states fail to do so, competition among neighboring states may emerge, with unpredictable consequences for the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment