Matthew Parris

Iawoke in the small hours last week and began worrying about the Ukraine war. A friend had earlier taken me to task over the airy way I’d introduced an argument with the words ‘Once we’ve won the war in Ukraine’ – as though this was a simple matter and just a question of ‘when’. But what does ‘win’ mean? Does the searchlight of our intelligence, backed by what we already know, really illuminate the landscape ahead? Might things come to pass that we just haven’t thought of?

Iawoke in the small hours last week and began worrying about the Ukraine war. A friend had earlier taken me to task over the airy way I’d introduced an argument with the words ‘Once we’ve won the war in Ukraine’ – as though this was a simple matter and just a question of ‘when’. But what does ‘win’ mean? Does the searchlight of our intelligence, backed by what we already know, really illuminate the landscape ahead? Might things come to pass that we just haven’t thought of?Even people as old as me remember wars that, though bloody and protracted, were fairly straightforward as narratives, with clear and final objectives and, in story terms, a reasonably clear-cut ending. The second world war is an outstanding example; the Falklands a more minor but equally clear case. We knew what winning meant. Hitler and Galtieri knew what losing meant. Even after the Korean war there was a simple and permanent partition. These were proper endings, followed by a stable state.

We imagine, I suppose, that the present Ukraine business will turn out like one of those. Crudely, I thought at first that the Russians should just be pulverised, Putin humiliated into personal collapse and all the territory Moscow had stolen returned to Kyiv. After that, I thought, Europe would be at peace again: stabilised, sorted and ready to help rebuild Ukraine.

But will it be anything like this? Let me throw into the mix of your own thoughts some doubts among mine.

Everyone is speculating on Putin’s leadership – will he be overthrown? Is his presidency strong enough to survive a peace deal with Ukraine and the West? Might he be replaced by a yet fiercer militarist? Good questions, but there’s another we don’t seem to be addressing: is Volodymyr Zelensky secure? Admittedly, my time spent travelled in Ukraine was short, and it was about 15 years ago, but it left me with a more jaundiced view of that country than one hears in these blue-and-yellow-flag-waving days.

Heroic though I believe Zelensky to be, his predecessors weren’t, and the political and business culture wasn’t

Ukraine is very populous, very poor and very far from the model of a modern, liberal, democratic western state that we might lazily suppose its people could skip happily towards ‘once the war is won’. Before Zelensky, we saw Ukraine’s political and business culture as hopelessly steeped in corruption, from the top down. Infrastructure and manufacturing (even before the Russian bombardment) were rusty and obsolete, making the country an industrial basket case utterly dependent on its most-favoured status with the old Soviet Union. Look at footage of the Ukrainian steel industry in the Donetsk region and remind yourself what a massive headache West Germany found it to drag East Germany into the modern European economy: talk about ‘levelling up’! Wealthy Germany is still wrestling with the cost, cultural as well as economic. We may one day wonder why we cheered the Ukrainian struggle to keep that Russian-speaking eastern rust belt.

It’s hard to see how Ukraine could stand up in the winds of free-market competition without a Herculean measure of assistance from the West. With a population exceeding 43 million (larger than Poland’s and not far short of Spain), a great mountain of support over many years will be essential if we’re to fortify democracy there once the Russian prop is withdrawn.

Western voters may enjoy watching the flashes and bangs of Ukraine’s valiant efforts in self-defence; we may cheer as British-donated weaponry arrives there. But once the pyrotechnics cease and our taxes rise to pay for reconstruction – and if there are more fake stories about Mrs Zelensky going on shopping expeditions to Paris, while rumours about where western money goes once it reaches Kyiv creep into the media – the spirit of unquestioning generosity may flag across the European continent.

Ukraine’s rapid accession to EU membership is surely for the birds. Free movement, with millions seeking better opportunities, would become a huge headache. One thing we and the EU single market could do to help, though, would be to extend a generous free trade deal to their emerging economy. The US did something similar for Mexico, but it caused fury as the American motor industry began to emigrate. Fasten your seat belts for something similar here as companies switch their manufacturing to low-wage Ukraine.

And is the country now – or could it fast become – a proper democracy, enjoying the rule of law, an independent judiciary, a professional civil service culture and vigilance over political corruption? Has everything about it changed just because one man, Zelensky, is in charge? You have to be a considerable devotee of the ‘Hero in History’ school to believe that a single individual can do so much. Heroes rarely last. Heroic though I do believe this Ukrainian president to be, his predecessors weren’t, and the political and business culture wasn’t. There was a chronic shortage of good, honest men and women at the top. If Ukraine was a rotten state, then in many ways it still will be, the suffering and sacrifice of its ordinary citizens notwithstanding. All-out war suppresses doubts about the polity whose preservation is being fought for. I don’t believe in transfiguration.

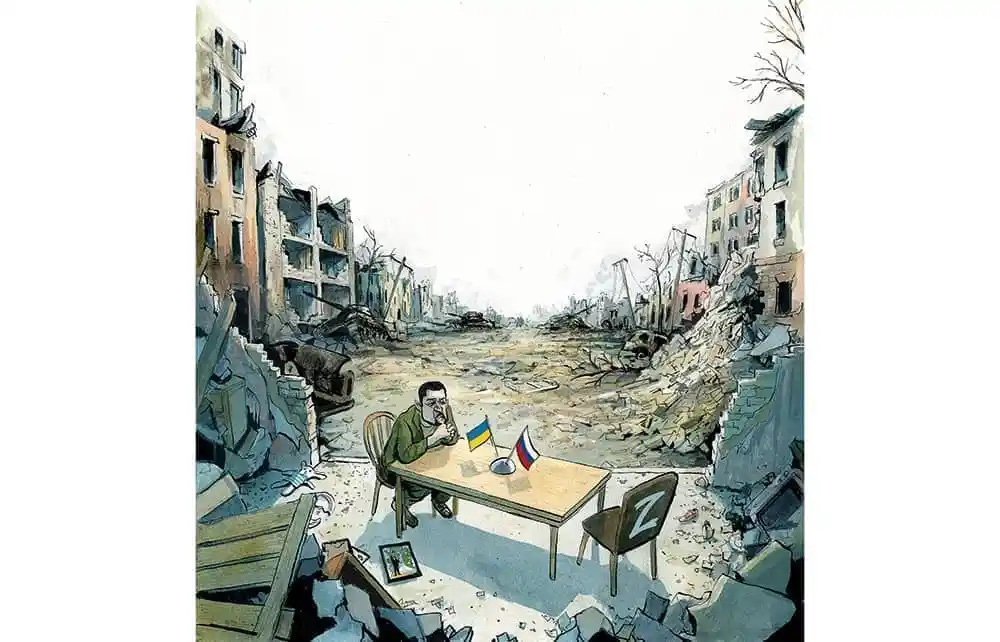

Let me leave you with a Grimms’ fairy tale no less implausible than today’s Walt Disney version. Imagine. It’s the winter of 2023/24. Putin or his successor inch towards a deal. Whispers of a compromise ceding Crimea to Moscow, or some such, circulate. Kyiv cries ‘Never!’. Biden, Scholz, Macron and perhaps (more quietly) Sunak/Starmer privately urge Zelensky not to make Crimea a deal-breaker. He hesitates, because a new ‘Ukrainian Patriot’ party is emerging on his militaristic right. ‘No surrender!’

No comments:

Post a Comment