Paul Heer

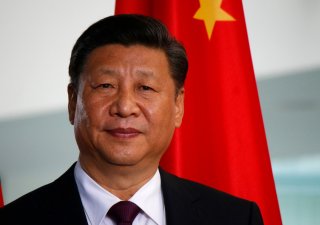

Secretary of State Antony Blinken will visit China in early February for a trip that was agreed upon during President Joe Biden’s meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping in Bali, Indonesia, on November 14. Blinken’s visit ostensibly aims to follow up on the understandings reportedly reached in Bali, especially the agreement—as characterized by the official White House readout of the summit—to “maintain communication and deepen constructive efforts” on a range of bilateral and global issues. The two leaders pledged to pursue such efforts through a “joint working group” and also “discussed the importance of developing principles that would advance these goals” and allow Washington and Beijing to “manage the [US-China] competition responsibly.” According to the Chinese readout of the Bali meeting, the two sides would “take concrete actions to put U.S.-China relations back on the track of steady development.”

Secretary of State Antony Blinken will visit China in early February for a trip that was agreed upon during President Joe Biden’s meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping in Bali, Indonesia, on November 14. Blinken’s visit ostensibly aims to follow up on the understandings reportedly reached in Bali, especially the agreement—as characterized by the official White House readout of the summit—to “maintain communication and deepen constructive efforts” on a range of bilateral and global issues. The two leaders pledged to pursue such efforts through a “joint working group” and also “discussed the importance of developing principles that would advance these goals” and allow Washington and Beijing to “manage the [US-China] competition responsibly.” According to the Chinese readout of the Bali meeting, the two sides would “take concrete actions to put U.S.-China relations back on the track of steady development.”In the two months since Bali, however, there has been little evidence of “concrete actions” or “constructive efforts” in that direction, involving either a joint working group or progress in the development of principles to guide the bilateral relationship. Yes, there have been additional high-level bilateral meetings: Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin met with his Chinese counterpart in Cambodia shortly after the Bali summit; Assistant Secretary of State Dan Kritenbrink and White House Senior China Director Laura Rosenberger traveled to Beijing in December to discuss Blinken’s upcoming visit; and Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen met Chinese vice premier Liu He in Zurich on January 18. But it remains unclear what if any substantive progress was made in those meetings: the U.S. readouts suggest that they largely consisted of exchanges of predictable talking points, and that American officials largely reiterated the need to “responsibly manage competition” and “maintain open lines of communication”—a minimalist phrase that has become Washington’s standard characterization of the current purpose of U.S.-China engagement.

In the meantime, Beijing and Washington appear to have essentially returned to the pre-Bali trajectory of mutual distrust and recrimination. Both sides continue to pursue policies that appear aimed more at competition and confrontation than at pursuing avenues for cooperation. This appears to have been clear even at Bali, when Biden (again, according to the White House summary of the meeting) emphasized that “the US will continue to compete vigorously with the PRC, including by investing in sources of strength at home and aligning efforts with allies and partners around the world.” Kritenbrink and Rosenberger reiterated this core message in Beijing before moving to “explore potential avenues for cooperation where [US and Chinese] interests do intersect.” More recently, White House Indo-Pacific Policy Coordinator Kurt Campbell reiterated publicly on January 12 that “the dominant feature of US-China relations will continue to be competition.”

Beijing has its own reasons for adopting a confrontational posture, including its growing belief—reinforced by recent evidence—that the United States is essentially undertaking an economic and science and technology (S&T) containment strategy toward China, while diluting its “one China” commitment regarding Taiwan. In response, Beijing is clearly pursuing a broad strategy of maximizing its global wealth, power, and influence relative to the United States, while affirming its will to fight over Taiwan. Chinese leaders are probably also hunkering down because they face domestic uncertainty and vulnerability in the wake of Beijing’s recent reversal of its “zero-Covid” strategy.

There are also multiple reasons for Washington’s own foot-dragging on substantive and constructive engagement with Beijing. The Biden administration certainly has been reluctant to assume the domestic political risks of appearing accommodative to an assertive authoritarian China, given the delicate balance of power in Washington. In the prevailing environment, anything that looks like (or is called) “engagement” is easily characterized and denounced as appeasement.

One recurring assertion in Washington is that the United States has on several occasions sought substantive dialogue with Beijing on key issues but has been stymied because Chinese officials have been unwilling or unprepared to meaningfully engage. It is more likely, however, that Beijing has not been willing to engage on Washington’s terms. Indeed, this was apparent during the Biden administration’s first high-level exchange with Chinese officials in Anchorage, Alaska, in March 2021, when Beijing’s then top diplomat told his American counterpart that “the United States does not have the qualification to say that it wants to speak to China from a position of strength.” Another senior Chinese diplomat, later addressing Washington’s call for “guardrails” for the U.S.-China relationship, said any such guardrails “should not be unilaterally set by the United States as a behavior boundary for China.”

There is an obvious symmetry here in Washington’s unwillingness to engage with Beijing on China’s terms. This was one of the reasons the Obama administration a decade ago ultimately dismissed a Chinese proposal for a “new model of great power relations”—because it was perceived as an attempt by Beijing to dictate the framework and terms for the relationship. In effect, both sides appear to believe that they have sufficient—if not decisive—leverage with which to resist making concessions to the other side or deferring to its preferences and priorities for the bilateral agenda. This is why Washington’s claim that Beijing is not seriously interested in negotiating on key bilateral issues is almost certainly mirrored by a Chinese perception that Washington itself is not genuinely interested in substantive talks. It appears that both sides would rather blame the other for obstructing—or trying to dictate—the agenda than acknowledge the limits on their leverage and the need to make some accommodations.

In the runup to Blinken’s visit next month, this equation has been reinforced by the apparent perception in Washington that the U.S. side may now have enhanced leverage over Beijing because Chinese leaders are simultaneously grappling with domestic problems (after the Covid policy reversal) and undertaking a diplomatic “charm offensive” to improve China’s global image in the wake of its earlier “overreach.” It is convenient for the Biden administration to calculate that this gives Washington the upper hand. But it invites the risk of mistaking a genuine Chinese desire to engage substantively on key issues—which, as noted above, U.S. officials are already inclined to dismiss as disingenuous—for a Chinese sense of vulnerability that allows Washington to respond minimally and/or try to extract unilateral concessions from Beijing. This is not hard to imagine, given that Washington itself probably assumes that any genuine U.S. eagerness to substantively engage with Beijing would be interpreted by Chinese leaders as a sign of American weakness and an opportunity to exploit.

Indeed, Beijing has expressed what almost certainly is a genuine—and greater—interest in constructive engagement. The Chinese readout of the Xi-Biden meeting in Bali was more extensive and detailed than the U.S. version on the need for sustained dialogue and on the range of bilateral and global issues that should be addressed through “strategic communication” and “regular consultations.” Moreover, Beijing has repeatedly criticized Washington’s characterization of the relationship as primarily competitive, emphasizing instead that bilateral cooperation should be elevated and maximized.

These themes have been echoed by Chinese foreign minister Qin Gang, who will be Blinken’s primary host in Beijing and who was just appointed on December 30 after eighteen months as the Chinese ambassador to the United States. On the occasion of his departure from Washington, Qin published two articles for the American audience, one in The National Interest and one in the Washington Post. In addition to invoking Xi’s messages in Bali, Qin wrote that the United States and China “should and can listen to each other, narrow our gap in perceptions of the world, and explore a way to get along based on mutual respect, peaceful coexistence, and win-win cooperation.” He reminisced about his frequent travels across the United States during his tenure as ambassador, and highlighted his extensive interactions with officials, scholars, businesspeople, and journalists: “Though we did not always see eye to eye, I appreciated their readiness to listen to the Chinese perspective.”

Predictably, Qin’s farewell articles were largely dismissed in Washington as typically lame and/or disingenuous Chinese efforts at public diplomacy. Indeed, they featured standard Chinese talking points on issues like Taiwan and Ukraine; well-worn propaganda about such things as Beijing’s pursuit of a global “community with a shared future for mankind”; and the recurring claim that responsibility for improving the U.S.-China relationship rests primarily with the U.S. side: “The Chinese people are looking to the American people to make the right choice.”

Qin reportedly received little high-level attention from the Biden administration during his tenure in Washington, partly because he was perceived as little more than a mouthpiece for such Chinese rhetoric, or as one of Beijing’s arrogant and obnoxious “wolf warrior” diplomats. The announcement of his appointment as foreign minister thus generated much commentary about whether this had been a miscalculation on Washington’s part. Some observers have dismissed the idea of a lost opportunity with Qin on the grounds that Beijing’s ambassadors and even its foreign minister are not really key players in the formulation of Chinese foreign policy. But this retroactive excuse appears only to reinforce the perception—in China and elsewhere—that Washington is unwilling to engage substantively with Beijing.

No comments:

Post a Comment