JOSHUA HUMINSKI

The war in Ukraine doesn’t look like it will end anytime soon. But there are plenty of lessons to be learned from the conflict, and planners in the NATO nations should be thinking them through. In this op-ed, Joshua Huminski of the Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress lays out the key points he believes NATO officials should be thinking about now.

In the Ukraine war, NATO’s success (by proxy) and Russia’s weakness presents an opportunity to reconsider the very force structure and design of the alliance. But that very success runs the risk of creating complacency. Seizing this moment requires Washington, Brussels, and European capitals to recognize the opportunity’s presence and act with alacrity, and not allowing the feared “brain death” of NATO to reemerge.

Perhaps the first and most pressing question that must be answered is what NATO’s purpose will be when the war in Ukraine eventually ends. The clearest answer is, naturally, returning to collective defense, focusing on European security, and deterring Russia. But bolstered by the additions of Sweden and Finland and the effective support against Moscow, leadership needs to ensure NATO doesn’t follow the path of the US national guard and become the solution for everything that has a security tie.

The organization must keep its strategic focus narrow — that aforementioned “brain death” was as much a lack of focus as it was a lack of urgency. NATO itself cannot solve every problem; it can be an addendum and a tool, but unless it addresses its central purpose of maintaining European security and deterring Russia, it will return to a state of missing focus. And now is the moment to consider what changes may be needed to ensure the alliance is strong, healthy and focused on its core task of keeping alliance members out of Russia’s grasp.

Structural reform requires a careful analysis and consideration of national military priorities, and planning to identify what capabilities are needed and how they will be met. Here, critical questions need to be asked: Does it make sense for every country to invest in and purchase mini-armies, or would purposeful force specialization make more sense for the long-term? Would it make sense for the United Kingdom to focus, as one of their senior defense leaders remarked to me, on the value-added capabilities such as high-speed fighters, cyber capabilities, and space? Would it make sense for Germany to take that €100 billion defense fund and, in addition to bringing the beleaguered Bundeswehr into the 21st century, focus on heavy tanks and artillery (though reports suggest Berlin is struggling to operationalize this fund)?

Verbal NATO spending commitments, while welcome, are likely to encounter domestic political reality checks in the face of an anticipated global economic slowdown and as competition for domestic spending increases. Will the United Kingdom be able to meet its pledged 3% of GDP defense spending when social and healthcare needs skyrocket in the near term? Signs suggest that Whitehall recognizes this is not viable.

The accession of Sweden and Finland represent opportunities to formalize existing, informal, joint operational planning and training, both of which are critical for the future of NATO. Stockholm and Helsinki operate robust and modern militaries, and their entry into the alliance should be smooth (although the sheer amount of staff work related to NATO may strain their smaller cadres). Regular rotations and deployments across Scandinavia and Central and Eastern Europe will only improve coordination and interoperability—key strengths of the NATO alliance — and serve as a signal to Moscow.

Here too, critical questions must be asked: what is the best allocation of forces? Are fixed deployments more appropriate versus more mobile, frequently changed rotations? This will, invariably, highlight differences amongst NATO allies. Estonia, for example, is likely to desire a more permanent and significant NATO presence (avoiding the “tripwire” model), whilst NATO HQ is increasingly aiming for more frequent rotations.

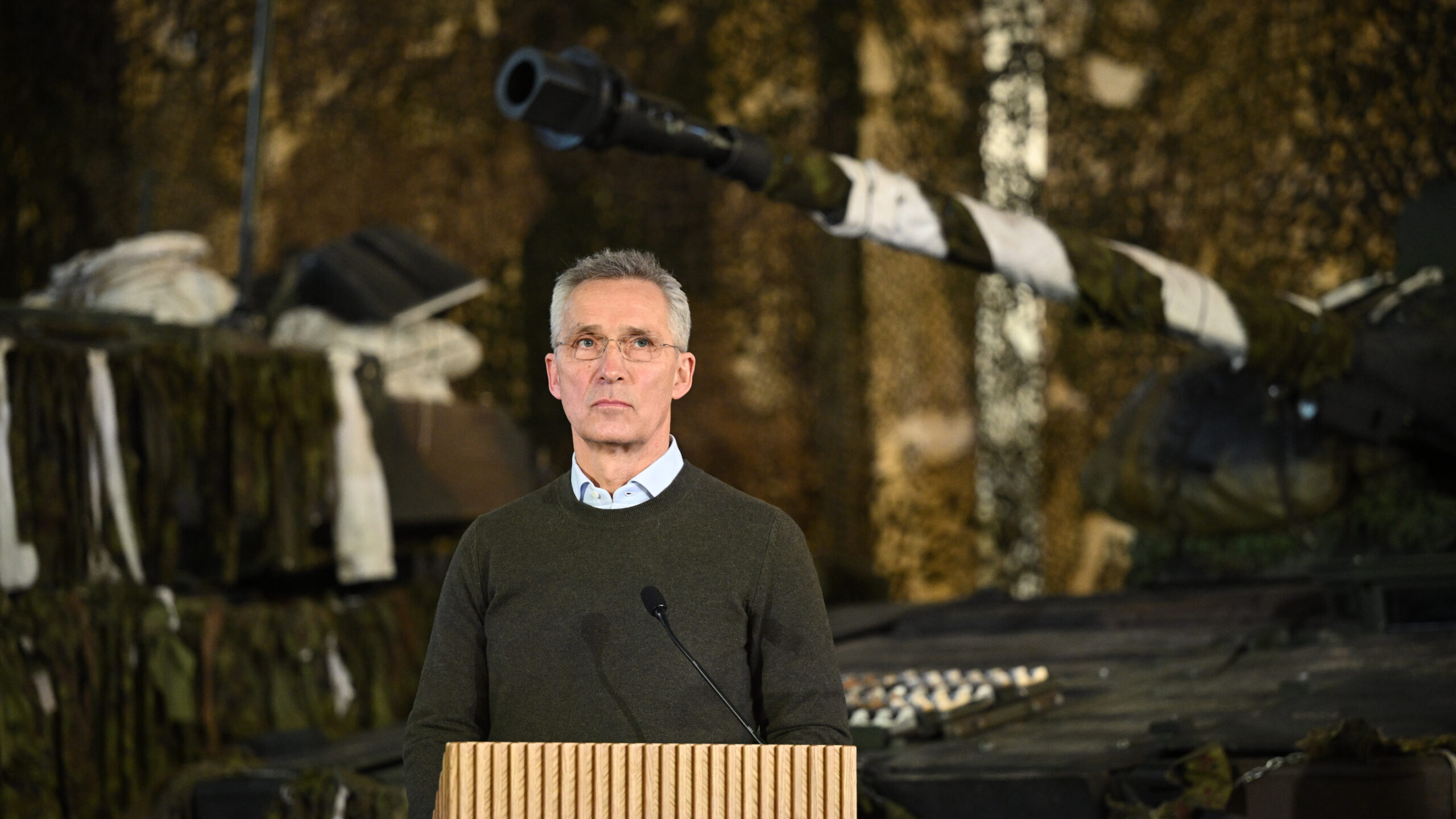

An emerging question is also the long-term relationship of Ukraine and NATO. At the end of November, NATO officials stressed their commitment for Kyiv to eventually join the alliance. According to Jens Stoltenberg, NATO’s Secretary General, “NATO’s door is open.” The provision of aid, development of military-to-military links between NATO and Ukrainian forces, and ongoing training that the foundations of a NATO-standard military are being lain, which would assuredly ease Ukraine’s membership — at least, on the field. The political challenges, which are not small, will remain, as they will across the alliance.

In fact, navigating the tumultuous exigent political relationships and dynamics will almost certainly grow as a challenge, as evidenced by Turkey’s opposition to Sweden and Finland’s membership in NATO. The complicated relationship of Hungary (which indicated it will ratify membership in the Spring of 2023, but remains a force of chaos within the European Union) with Russia will also complicate NATO’s political machinations. Managing an alliance in which not all parties equally appreciate the immediacy of the threat, especially in the face of a weakened Russia, will require diligent effort from Brussels and whomever occupies the Secretary General’s seat.

There is also the open question as to the balance of responsibility and division of labor between the European Union and NATO when it comes to continental security. The latter clearly has the capabilities and the defense expertise, while the former has considerable financial and civilian resources. What this looks likes could well inform NATO’s mission set and prioritization.

The force design and structure will require an updated and comprehensive assessment of what Russia’s military will look like and what strategic threat Russia will pose to Europe in a post-Ukraine world. While much is unknown (not the least of which is the outcome of the war in Ukraine) arguably, and based on its not inconsiderable losses, the conventional threat will have been dramatically reduced. Determining what the Russian threat will look like in the near- to medium-term is critical to informing NATO force design and force structure.

The West’s sanctions and technology embargos will make rearming exceptionally difficult, though not impossible. North Korea is one of the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world, yet continues to make improvements in its ballistic missile and nuclear weapons programs. Moreover, despite the imposition of punitive trade sanctions and sharply limiting Russia’s access to Western technology, Moscow will undertake a concerted effort to rearm. That timeline is unclear: analysts have speculated anywhere from two to three years at the low-end to over a decade at the high-end. Yet, this rearmament will only get Russia back to its February 2022 level. While Moscow struggles to rebuild its conventional forces, NATO militaries will be continuing their own modernization programs (while incorporating lessons learned from Kyiv’s successes the Russian military), while re-arming and restocking on spent munitions sent to Ukraine.

Moscow’s cyber, space, strategic arms, and unconventional warfare capabilities have not suffered nearly as much, or indeed at all. Russia will also find it more attractive to revert to political or informational warfare to pursue its aims in the near-term, to offset Russia’s perceived (and real) conventional weakness in a post-Ukraine world. European and American efforts thus far to limit the efficacy of Russia’s political warfare campaign are to be welcomed, but must be sustained.

Perhaps the biggest challenges for NATO will not be those related to the alliance itself or indeed Russia’s military posture, but the internal balancing of national-level interests and considerations amongst individual member states. Domestic political and economic pressures are likely to absorb more time and attention in the coming months.

As the immediacy of the threat from Russia ebbs and, particularly as Ukraine continues to make advances, the urgency for reform in the face of a weakened Russia will decrease. Yet, failing to act today risks missing a generational opportunity to reform NATO for the 21st Century, something it has sorely needed and will need regardless of the outcome of the war in Ukraine.

No comments:

Post a Comment