Ahmed Alqarout, Ali Ahmadi

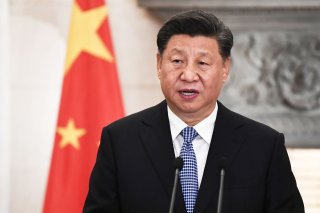

Chinese president Xi Jinping’s recent trip to meet with the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) set off a storm of anxiety in Washington. But it’s important to note that much of what was agreed to in these meetings is actually designed to marginalize Iran in regional and trans-regional affairs—a cause shared by the United States and many of its GCC partners.

The Saudi Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement with China comes just two years after Beijing signed a similar deal with Iran. The timing of the deals is thus not a coincidence but a calculable act by Saudi Arabia to contain Iran and curtail any gains it may have secured through such a strategic partnership. Hence, despite popular belief to the contrary, the United States stands to gain from the agreement, which will help ensure Iran's regional and global power remains checked.

Iran and Saudi Arabia Look East

The Saudi-China strategic partnership should not be seen in isolation from the other agreements Riyadh has advanced in Asia. In a way, Saudi Arabia’s “Pivot to Asia” is its answer to Iran’s “Look to the East” strategy. Iran’s strategy was adopted by conservatives who see Asia and Eurasia as key avenues to expand Iranian influence at the expense of ties with the West. Thus, Saudi Arabia aims to contain Iran’s strides in Asia, supplementing similar U.S. efforts. Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries have been signing deals with Asian countries that Iran seeks stronger ties with to relieve itself from Western economic pressure. In the past two years, Riyadh has signed economic, diplomatic, and defense agreements with Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Kazakhstan, and Bangladesh, to mention a few. Therefore, Saudi Arabia’s closer ties with China should be seen as part of its efforts to contain Iran’s growing relationships in Asia and as a response to the Raisi administration’s shift away from the West.

By signing the China-Saudi Arabia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement, Saudi Arabia has cemented its economic partnership with China, which was already thriving, in a bid to limit the possibility of China moving closer to Iran. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, the trade volume between China and Saudi Arabia stood at $65 billion in 2020. The volume of trade in the same year between Iran and China lagged behind at $14.5 billion. The significant gap is partly explained by Western sanctions constraining Chinese companies’ ability to trade with Iran and vice versa. Nonetheless, the signing of the China-Iran Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2020 had the potential to boost the volume of trade between the pair.

Furthermore, as the West threatens to sanction China and imposes broad sanctions on Russia, Riyadh is worried that a sanctioned China will seek to boost trade with Iran, as they both aim to resist Western economic statecraft. This was the case with Russia. Since the imposition of sanctions on Russia, Iran has sought to capitalize on the situation, signing large trade deals with Russia that have significantly boosted the volume of trade between the pair, which stood at only $4 billion as of 2021. For example, Iran signed $40 billion worth of gas deals with Russia's Gazprom. There has also been a significant influx of Russian businesspeople and private sector interest in Iran over the past month and a greater emphasis on major joint infrastructure programs. Thus, Saudi Arabia worries that Iran’s trade with China will grow and tilt the balance in favor of Iran. The Saudi strategic partnership with China ensures that trade between Iran and China remains well below its own, maintaining the balance of power against Iran.

These efforts should also be seen as part of Riyadh’s desire to contain Iran’s championing of emerging non-Western-dominated international organizations. Iran is being elevated to full membership in the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and has applied to join the BRICS bloc led by Russia. Saudi Arabia worries that Iran’s growing importance in such alternative trade and security blocs will offer Iran relief from Western sanctions and enable it to continue pursuing regional activities that undermine Saudi interests. Saudi Arabia applied to join BRICS shortly after Iran filed its membership application and is considering joining the SCO along with Qatar and Bahrain. Furthermore, Riyadh’s commitment to connecting its Vision 2030 with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is also part of its effort to decrease Iran’s chances of being a key beneficiary of the BRI and ensure that China continues to hedge its BRI investments. The Saudi government is also seeking to make Chinese companies base their regional headquarters in the kingdom as part of its steps to ensure its economy dominates the Middle East. This will ensure that Chinese companies approach Iran as a second-priority market, not a strategic one, helping to undermine Iran’s effort to become a regional investment and trade hub for China and others.

De-Dollarization and Critical Infrastructure

On the geo-financial front, Iran and China have been pursuing the de-dollarization of trade and advancing the idea of the “petro-yuan.” By joining the SCO, a key international platform pushing for global de-dollarization, Iran can be a key regional power promoting that agenda. Not only would this help Tehran overcome Western sanctions, but it could also make it the most experienced and capable country in the region with the infrastructure to enable trade in non-dollar currencies. Thus, it is no coincidence that China called Saudi Arabia to join this effort and sell its oil in yuan. While Riyadh remains committed to selling energy exclusively in dollars, the China-Saudi partnership summit makes the “petro-yuan” an official objective, giving Saudi Arabia the ability to exercise that option in the future, especially if Iran advances de-dollarization as a result of its partnership with China. Largescale sales of petroleum through yuan-based contracts may not be possible in the immediate future, but the prospect of such a move would be worrying to Washington due to the importance of dollar-centered energy markets to the dollar’s status as the world’s dominant currency.

The Saudis are also eager to contain Iran’s technological advancement and growing military edge. The Iranian industrial base is perceived by Saudi Arabia as a threat that helps Iran export missiles, drones, and advanced communication technologies in the region, undermining Saudi interests. By warming up to China, Saudi Arabia is seeking to capitalize on China’s industrial capacity to build an advanced industrial base. Thus, China welcomed Saudi sovereign wealth fund investments in its industrial sector, which will help Riyadh gain knowledge to advance its industrial base and maintain the industrial balance with Iran. An agreement to build a drone factory in Saudi Arabia, while signed before the strategic partnership, complements Riyadh’s efforts to ensure the balance of power between Saudi Arabia and Iran remains checked. Of course, Saudi Arabia has access to Western arms that Iran lacks, but it is seeking to develop its indigenous military-industrial capacity.

A potential major area of diversion between the United States and Saudi Arabia is Riyadh’s deal with Huawei to build cloud computing capabilities and high-tech complexes in Saudi cities. Several U.S. officials have warned Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries against using Chinese technologies, especially in the 5G realm, and threatened them with sanctions. However, Saudi Arabia’s seeming defiance remains understandable in the context of competition with Iran. As a sanctioned entity, Huawei is more comfortable working with Iran and offering it advanced capabilities. This would most certainly give Iran a competitive edge vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia, which was cautious not to introduce China to its telecommunication and technology sectors for fear of U.S. retaliation. By contracting Huawei, Saudi Arabia aims to gain new technologies and offer Huawei the opportunity for a more balanced relationship with Iran.

The agreement’s commitment to renewable investment is key to Saudi efforts to contain Iran’s rise. Iran has pursued growth in its renewables industry in a bid to diversify its economy, strengthen its technological capacity, and secure new regional and international partnerships, including with China, which will help it overcome sanctions. GCC countries have been helping Yemen, Iraq, and Syria reduce their reliance on Iranian hydrocarbons by encouraging the use of renewables through initiatives and investments. With the signing of the deal with China, Saudi Arabia aims to gain an edge in the renewables sector, which will undercut Iranian energy sales in the region and beyond. China, as a leading power in renewables, stands to help Saudi Arabia achieve such objectives at the cost of Iran’s aspirations, which are already held back by Western sanctions.

Despite the major achievement for China, it did not get all it wanted from Saudi Arabia. Particularly, China has called upon Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states to establish a Free Trade Zone (FTZ). Discussions around such a zone have been ongoing for years and were recently emphasized by the Chinese. However, Saudi Arabia and other GCC nations are still resisting an FTZ, and the strategic partnership merely mentions the negotiations but does not commit to them. This is an area where Iran has leverage over China, as it is signing an FTZ agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union and is willing to sign a similar one with China under the right circumstances. The lack of Saudi concessions on the matter suggests its openness towards China is not unrestricted and remains mostly geared towards weakening Iran rather than empowering China in the Gulf and the Arab world.

Saudi Arabia’s pivot toward China ultimately complements U.S. efforts to contain Iran and, despite how it may appear at first glance, does not seriously undermine American interests. This may help explain the Biden administration’s muted response to the Saudi-China strategic partnership.

No comments:

Post a Comment