With plans now underway to equip Ukraine’s armed forces with America’s Patriot Air Defense System, the internet is aflutter with debate about just how effective it really is, and whether or not it stacks up against its Russian competition.

The MIM-104 Patriot Air Defense System first entered service in the early 1980s as a replacement for both Nike Hercules high-to-medium air defense and MIM-23 Hawk medium tactical air defense systems. Today, the Patriot is operated by 18 nations, with the United States operating the largest fleet of systems, with 16 Patriot battalions operating upwards of 50 Patriot batteries that have more than 1,200 interceptors in the field.

In comment sections and forums around the world, you’ll find no shortage of self-appointed air warfare experts citing seemingly imagined statistics about American, Russian, and other air defense platforms to justify their hyperbole… But the complicated truth about air defenses at large comes in the form of two equally hard-to-swallow pills for those waging war in the comment section:

1. Publicly-released details about most air defense systems tend to be as rare as they are dated.

2. Air defenses at large are simply not as effective as they’re often perceived to be.

However, with those two points in mind, the evidence seems clear that the MIM-104 Patriot is among and potentially even the most effective air defense system in the world. But if that’s the case, why is it so often dismissed, while Russia’s S-400 is so frequently touted as practically invincible?

The truth is, understanding how perceptions of the Patriot system relate to the platform’s actual performance requires a pretty thorough understanding of not only the complexity of the air defense enterprise… but also the marketing tactics leveraged by nations fielding different systems.

The world’s first air defense system to shoot down a missile…

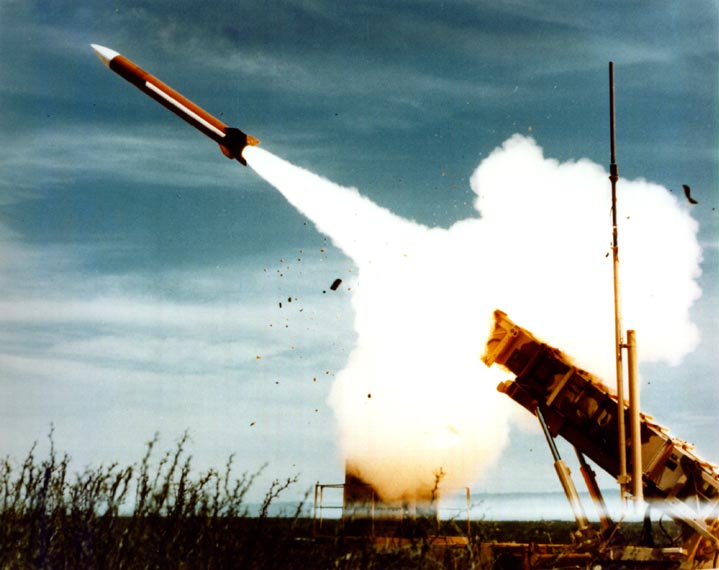

Patriot air defense system (DoD photo)

On January 18, 1991, a CNN crew recorded from Saudi Arabia as an American Patriot system was used for the first time to engage a reported incoming Scud missile. The SS-1 Scud was a post-World War II tactical ballistic missile developed by the Soviet Union and based on Germany’s V-2. Iraq operated a modified iteration of the upgraded Scud-B during the Gulf War.

“There’s a streak of light,” Charles Jaco, of CNN, said describing the intercept, “The [Patriot] missile goes North, cants slightly to the East, goes North again, disappears into the clouds, and then there’s an illuminating flash…”

It wasn’t until later that the Department of Defense would admit that the internationally lauded Patriot intercept caught on camera hadn’t actually occurred at all. Iraq had never fired a Scud missile into Saudi Arabia that day, and instead, the Patriot system had fallen prey to a false alarm and gone after it. Because of the cloud cover obscuring everyone’s view, the assumption when no Scud found a target was that “the Patriot did its job perfectly” — which is a direct quote from ABC News correspondent Forrest Sawyer at the time.

While this may have been nothing more than an honest mistake, analysts would continue to question the claimed efficacy of the Patriot system throughout and well beyond the conflict. The Patriot did eventually become the first system to ever intercept an inbound ballistic missile, but as the war went on, the Army claimed the Patriot had an 80% success rate in Saudi Arabia and 50% in Israel. Not long after, the Army reduced those figures to 70% and 40%, but many within the United States still weren’t buying it.

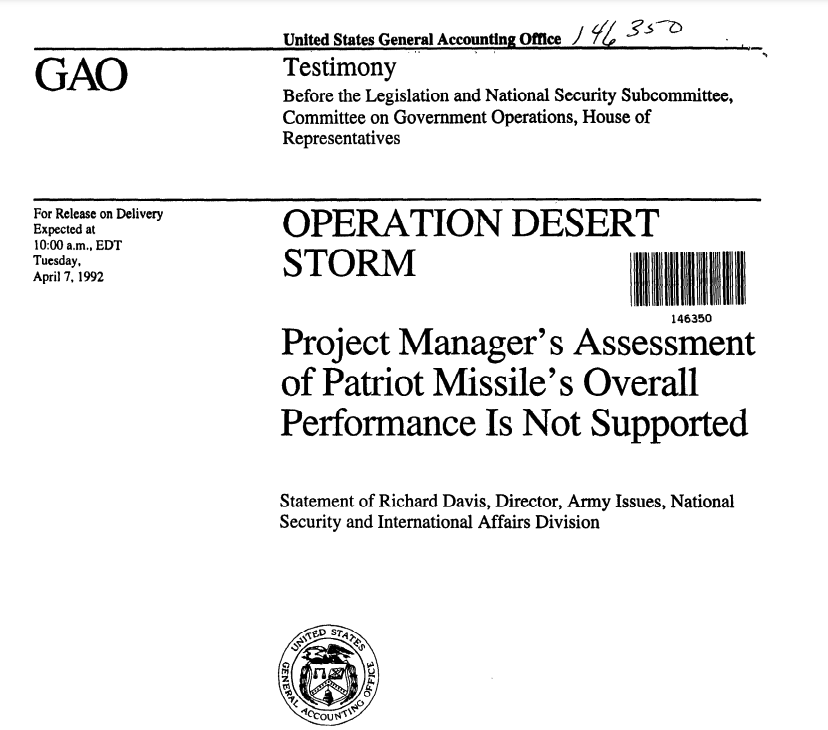

After a 10-month investigation by the House Government Operations Subcommittee on Legislation and National Security also seemingly questioned the Army’s claims in 1992, the General Accounting Office also started looking into the Patriot’s efficacy. Before long, these investigations prompted a flood of negative press coverage, and as a result, the Patriot system soon became known as an ineffective system.

Did the Patriot system really only intercept 9% of Scuds during the Gulf War?

(Image created by Alex Hollings using U.S. Army photos)

These investigations and the media’s depiction of their findings continue to define the Patriot system in the minds of many to this day, but like stories we’ve covered in the past about the F-35 or F-22 failing to live up to expectations, it’s important that we recognize the media value a story about touted American systems failing has in terms of viewers, readers, and clicks.

Painting a dire picture of the Patriot’s performance in Iraq is sure to drive much more engagement than one about the system’s mediocre performance. But, it’s also important to sift through the context-less hyperbole to acknowledge the very real limitations the Patriot system demonstrated throughout this conflict.

The House Government Operations Subcommittee report on the Patriot’s performance during the Gulf War ultimately concluded that evidence of successful intercepts of inbound Scud missiles was rather limited, though that report itself was subject to a great deal of internal debate resulting in only a draft written by one staffer finding its way to the media and no formal report ever manifesting.

But it was the GAO investigation that gave the Patriot’s critics their most damning talking point.

According to their findings, only about 9 percent of Scud intercepts by the Patriot system during the conflict “are supported by the strongest evidence that an engagement resulted in a warhead kill.”

This 9 percent figure seems really bad — even worse when compared to the Defense Department’s claims of 70% and 40% success rates in Saudi Arabia and Israel respectively. Raytheon, however, had a valid rebuttal that tends to be glossed over by critics of the system.

U.S. Army Patriot air defense system during a test fire (U.S. Army photo)

“The General Accounting Office (GAO) report did not state that Patriot had only a 9% success rate and did not dispute the U.S. Army’s overall 60% success rate,” Raytheon clarified. “The GAO report never voiced any disagreement with the Army’s overall assessment that Patriot was successful in over 70 percent of the SCUD engagements in Saudi Arabia and over 40 percent in Israel. In its assessment of Patriot performance, the Army analysis subdivided Patriot intercept successes into ‘warhead kills’ and ‘mission kills.’ It then further subdivided each of these categories into ‘confidence levels’ based upon how much supporting data was available.”

Put simply, within the GAO’s investigation, they sorted intercepts into multiple categories, with the “highest confidence” category reserved for “the strongest evidence that an engagement resulted in a warhead kill” — requiring either the recovery of Scud debris showing clear Patriot damage or a saved radar record that clearly showed Scud debris on radar following an intercept. Amid the fog of war, this sort of evidence is obviously difficult to come by, which is why the GAO didn’t claim only 9% of intercepts were successful, but rather that they were able to secure this sort of conclusive data from only 9% of attempts.

The truth about the Patriot system in Iraq is simple: A crappy beginning followed by a triumphant return

Patriot air defense system live-fire testing (U.S. Army photo)

Of course, if we’re willing to acknowledge the media’s preference for an exciting (if damning) story, we certainly need to consider Raytheon’s obvious bias when defending a multi-billion dollar system of their own creation. And while their rebuttal did poke holes in the media narrative surrounding the Patriot’s failure, it still painted a rosier picture of the system’s performance than was probably warranted.

To that end, we reached out to a popular TikTok content creator and U.S. Patriot Fire Control Enhanced Operator-Maintainer, who asked to simply be identified as Sergeant First Class (SFC) Long. Long is an active-duty subject matter expert tasked with the placement, operation, and maintenance of the Patriot Fire Control system.

“In the first Gulf War Patriot was right around 25%. It was doing something it wasn’t necessarily designed for. It was actually built for planes but they decided to throw it at missiles and it sometimes hit. Since then, we have vastly improved the system — like hundreds of upgrades.”

Long’s claim of a 25% success rate is in keeping with the Government Accounting Office’s own conclusions about the Gulf War. And his assertions about the system’s progress since are also substantiated in the data. While the Patriot system did struggle against Iraq’s “Al Hussein” model Scud-Bs during the Gulf War, things were quite different when the Patriot returned to Iraq a bit more than a decade later.

“In contrast with the experience of Desert Storm, Patriot interceptors defeated every ballistic missile they engaged during the 2003 Operation Iraqi Freedom. Since 2015, Patriot has successfully engaged scores of missiles and drones in the Yemen Missile War. Israel has likewise used it on a number of occasions to defeat drones, aircraft, and other threats.”

“Patriot to Ukraine: What Does It Mean?” by Mark Cancian and Tom Karako for the Center for Stratgic & International Studies, Dec. 16, 2022

And while CNN may have missed the mark in their 1991 coverage of what they believed to be the first Patriot intercept, another CNN crew found itself present for what really was a successful intercept in March of 2003… but they weren’t able to report on it.

“Had anyone reported this – had we reported it, or had it gotten out,” CNN national security analyst Ken Robinson later explained, “it would have enabled [Iraq] to know that they had the exact grid coordinate they needed” to target the headquarters of coalition ground forces.

How governmental transparency affects perceptions of the Patriot air defense system, as well as its Russian peers

S-400 live fire testing (Russian Ministry of Defence)

When discussing the Patriot air defense system online, it’s impossible to avoid comparisons with its Soviet and Russian counterparts, systems like the S-300, S-400, and the latest S-500. Unlike the Patriot system, which tends to have a tarnished reputation in the minds of many, Russian systems are often highly touted as the best in the world. Of course, since the onset of fighting in Ukraine in February of 2022, Russia’s longstanding approach to conveying an unwarranted image of military prowess has finally become broadly recognized — and as we’ve discussed at length in our deep dive into the S-400, the air defense enterprise is no exception.

Russia’s air defense systems, like so many of the nation’s military endeavors, benefit from a very intentional perception-management campaign enacted by the Russian government and bolstered by countless Russian-state-backed media outlets operating all around the world. The myth of Russia’s impenetrable air defenses, it’s important to understand, is vital to Russia’s efforts to court foreign buyers for these systems, as the Russian military is reliant on foreign investment to fund its own advanced developmental weapons programs.

So why, then, is there such a disparity between popular perceptions of America’s Patriot air defense system and Russia’s S-400? A great deal of that comes down to something as simple as American transparency juxtaposed against Russian information operations, as well as the overall level of secrecy surrounding all air defense platforms regardless of national origin.

This point was made succinctly in a broader piece about the overall effectiveness of air defense systems published by the Nuclear Threat Initiative in September 2020:

“The United States is by far the most transparent of countries when it comes to missile defense tests, yet even reports from the United States provide only superficial details about most tests,” the report explains.

Americans are accustomed to a level of governmental transparency in which governmental bodies themselves will hold other governmental organizations accountable.

As the report states, American air defense systems of all kinds have consistently demonstrated a high degree of efficacy over time, despite some rocky starts. Between 1963 and 2020, the U.S. conducted a total of 121 disclosed test intercepts with various systems, with an overall success rate of a respectable 72 percent and generally high success rates once a program reaches maturity.

It goes on to compare American transparency to Israel and Japan, before questioning the transparency of Indian efforts, and finally highlighting Russia’s apparent tomfoolery. Americans, by and large, tend to assume all governments are similarly transparent about the successes and failures of their defense programs, but that’s far from the truth.

“Perhaps most questionable of all are Russian missile defense claims. Although it is not alone in so doing, Russia has made spectacular claims about the success of the S-400, yet there are few public reports about individual tests of the system.”

S-400 launchers (Russian Ministry of Defence)

According to NTI’s findings, Russia has only disclosed successful tests of the S-400 system, effectively suggesting that it required no development whatsoever and emerged fully formed and infallible. Russia has not disclosed the circumstances of the tests, the number of interceptors launched, the types of targets, or their level of capability… they’ve simply claimed 100% success rates and offered little more.

Of course, in real weapons development, that’s an extremely unlikely scenario — and following Russia’s performance in Ukraine, it seems even less likely.

“To date we have not been able to identify any reports of failed intercept tests involving the S-400. Like our hypothesis involving India, this suggests Russia is concealing most of its developmental tests or other failed intercepts. “

“The Global Missile Defense Race: Strong Test Records and Poor Operational Performance” by Shae Cotton and Jeffrey Lewis for the Nuclear Threat Initiative, Sept. 16, 2020

But while Russia’s claims of success with the S-400 (which have been clearly called into question by actual combat data) may not be trustworthy, it is nonetheless important to understand that the S-400, like most Russian air defenses, is likely a pretty capable system, as evidenced by the laundry list of foreign buyers.

The actual efficacy of the S-400 has been called into question many times, despite Russia’s claims of 100% success rates.

The plain fact of the matter is, however, no system is as good as Russia tells the world their systems are — but while many take their claims at face value, few recognize the disclosed progress made by the Patriot system since its rocky start.

“Now days, Patriot has right around a 95% hit ratio,” Long explained.

The Patriot system isn’t meant to operate on its own (and neither is the S-400)

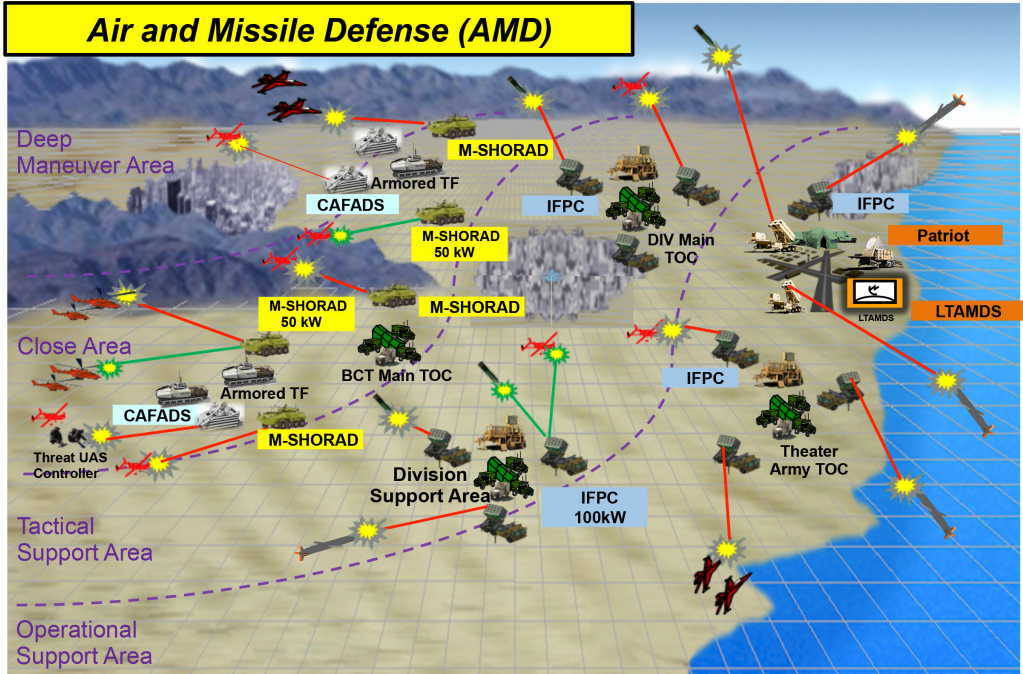

The U.S. Army’s “Defense in Depth” approach to air and missile defense (AMD). (U.S. Army)

Perhaps most important of all, directly comparing these systems is, in itself, a missed intercept. The Patriot air defense system, like Russia’s S-400, isn’t intended to serve as a stand-alone system. Both of these platforms are meant to play a role in a broader networked integrated air defense apparatus, and both can only see their best performance as a part of that larger network.

The United States, for example, leverages overlapping air defense systems of different sorts (an approach Long and the Army refer to as “defense in depth“). This approach means that as an inbound missile gets closer to your defended asset, it faces an increasing amount of defensive firepower.

In other words, directly comparing the Patriot system to the S-400 is sort of like comparing the transmissions in two different race cars. We can debate all day about which is better, and there is some value to that discussion, but what really matters is how well the whole car performs when assembled and in a race.

Today, the available data seems to suggest that America’s THAAD and Patriot air defense systems may be the most successful of any systems in actual combat environments — but importantly, that success is, in itself, relative.

Intercepting a wide variety of inbound missiles is an extremely difficult job, and the fact of the matter is, in a saturation attack, especially involving low-flying cruise missiles in contested airspace without AWACS support, just about any modern system is likely to fail.

Air defense intercepts are an unforgiving science, which lends itself to a lack of transparency even within more open governments like the United States. But it’s important to consider how America’s broader transparency can affect perceptions when juxtaposed against the objectively untrustworthy claims of the Russian government.

No comments:

Post a Comment