Are new winds blowing in China’s relations with Middle East states, or are they essentially more of the same? The visit by China’s President to Saudi Arabia was heralded as a “new era,” but what does this mean, and what can be understood from Beijing’s various statements about how it sees the region? Most important, how do these developments reflect China’s attitude toward Iran?

In December 2022 Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia and held a series of summit meetings with leaders of Arab states in general and the Gulf states in particular. Before, during, and after the visit, various headlines trumpeted a “new era” of Chinese relations with the Middle East, while speculating in this context as to China’s Iran policy. Yet while there were some developments in these relations, in many respects, little is new – although sometimes, continuity itself can point to what is new. What are the new developments, what is not actually new, and how does this issue relate to Israel?

China at the Center

Prior to President Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia, Chinese newspaper editorials declared that the visit would “strengthen cooperation between China and the Arab world further, promote peace and prosperity in the region, and pave the way for building a Chinese-Arab community with a shared future for a new era.” A document by the Chinese Foreign Ministry, which laid the basis for the visit several days before it occurred, was entitled “Report on Cooperation between China and Arab States in the New Era.” The President himself used the term “new era” to mark the progress in relations between China and Arab states, and especially Saudi Arabia. This term – “new era” – is not part of a spiritual, New Age-y lexicon, but reflects the worldview of the Chinese Communist Party in the last few years (particularly since 2017) and the vision of the President, known as Xi Jinping’s “Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” – a vision that was also enshrined in the party’s constitution. The historic perspective of the party was presented in November 2021 in the “Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century.” This document has major significance in terms of the Party’s approach to history, not only for structuring the narrative of the Party’s past, but because the President and the Party see history as the most significant factor in thinking about the future. Similar resolutions have been presented only twice before: in 1946 by Mao Zedong, and in 1981 by Deng Xiaoping; in both instances China faced central historic junctures in its history. The first was the civil war, after which China established the People’s Republic of China; the second was when China embarked on a path of openness and reform after almost thirty years under Mao’s rule.

The 2021 resolution divided the Party’s 100 years into three eras: 1) “The New-Democratic Revolution,” from the establishment of the Party in 1921 to the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949; 2) “Socialist Revolution and Construction [of the State],” from the establishment of the PRC until 1978; 3) “Reform, Opening, and Socialist Modernization,” from the rise of Deng Xiaoping to the beginning of Xi Jinping as Party secretary-general at the end of 2012. In addition to the descriptions of these three eras, which highly praise Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, the resolution adds the “new era” of President Xi. At the core of this new era is the paradigm shift in the history of modern China: a change that is both qualitative and quantitative in China’s successes, and in addition – in the context of the Middle East – a change in China’s global status, with China assuming the central role from the last decade and into the future.

This new era of Chinese centrality, as mentioned in the President’s speeches and in Chinese headlines, is the heart of the matter from the Chinese perspective – far more than a new era between China and the Arab states, as it was portrayed by the non-Chinese press. In this sense the competition between China and the US, which is discussed constantly, is secondary, or is at most a means to achieve Chinese centrality on the global stage. This is the context in which President Xi’s discussion of “building a Chinese-Arab community with a common future” should be understood. The term “community with a common future” is inherent in the perspective of Xi’s “new era,” and alongside his inclusive rhetoric – the term relates to the global community as a whole, which shares a common future of prosperity and cooperation (“win-win”) – he also emphasizes, in Chinese publications, the centrality of China in that common future. These terms are at the basis of all Chinese international initiatives in recent years, including the Belt and Road Initiative. In other words, while the rhetoric appears egalitarian and inclusive, a deeper look at the ideological element of the statements reflects a hierarchical perspective of Chinese superiority.

Is the “China-Iran-Russia Axis” Weakening?

One of the issues that made headlines after the Mideast visit and especially after the joint statements released following the various summit meetings was the issue of Abu Musa Island and the Greater and Lesser Tunb islands (the “islands issue”), in the strategic area by the Straits of Hormuz. Iran conquered these islands after the UK withdrew from the region in 1971, and since then sovereignty over them has remained a major bone of contention between Iran and the Emirates. In a joint declaration by China and the Gulf states (the GCC), it was explicitly stated that China supports reaching a solution to the islands issue through “peaceful efforts.” Commentators seized upon this wording as if they had found a treasure: here, they propounded, is proof that China supports the Gulf states against Iran, and even, according to Iranian news sections, is “betraying Iran.” Others went as far as to connect this clause in the joint statement (section 12) to discomfort in Beijing at Iran’s involvement in the war in Ukraine, and especially about the transfer of weapons from Iran to Russia. They thus concluded that there is ostensibly a rupture in the “China-Iran-Russia axis.”

However, from the Chinese point of view, the islands issue is more complicated. First, it is important to understand that China has consistently seen and presented this issue as an outgrowth of Western imperialism and colonialism. In other words, China has emphasized repeatedly that major global problems result precisely from the Western “world order,” which the West purports to present as a solution. This framing of such issues is quite widely accepted in China and can be found in conflicts that involve China itself, such as the unstable border conflict with India. This view posits, in accordance with the current Chinese worldview, that in the “community with a common fate” with China at its center, such issues would not arise on the one hand, and if they did, would be resolved peacefully on the other.

Furthermore, in contrast with the assumption that the current statement reflects a new element regarding China’s approach to the islands issue, previous statements from similar summit meetings over the past two decades show that the same clause was included in those declarations for some time. In fact, the wording is nearly identical: the joint declarations, for example, from 2006, 2008, 2018, 2020, and others all contain a clause that conveys this exact content. For example, section 12 in the current document is completely identical (other than a few words at the beginning, which note that the leaders of the states themselves emphasize the issue – a common phrase throughout the document) to the section on this subject (section 22) in the 2020 document. The islands issue, which many recent commentators have marked as demonstrating a change in direction by Beijing, actually demonstrates a stark continuity, without almost any change and certainly no paradigm shift.

In contrast, sections 9 and 11 are somewhat different. Section 9 emphasizes the importance of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the prevention of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction in the region, and the need “to ensure the peaceful nature of the Iranian nuclear program, in order to safeguard regional and international security and stability.” In particular, the sides call on Iran “to fully cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency” in this context. In section 11 the leaders jointly call for a “comprehensive dialogue” with the participation of regional states to address “the Iranian nuclear problem…destabilizing activities threatening the stability of the region, support for terrorist organizations, sectarian groups, and illegal armed organizations,” “prevent the proliferation of ballistic missiles and drones,” “ensure the safety of international navigation and oil installations,” and “adhere to UN resolutions and international law.”

To be sure, similar sections can be found in a variety of previous statements. However, in sections 24 and 25 from the 2020 statement, which relate to similar issues: 1) Iran is not mentioned explicitly in any of the relevant sections, and is only mentioned in section 23 (the equivalent to section 10 in the current statement) in the context of a general statement of hope for good neighborly relations among states in the region. 2) Iran is thus not explicitly linked within specific sentences to issues ranging from terror to the nuclear program. 3) On the nuclear issue specifically, for example, the sections in the 2020 statement discuss in very general terms the importance of preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the importance of joining the NPT, without mentioning Iran at all. 4) In a similar fashion, the discussion of terror is completely generalized, while ballistic missiles and drones receive no mention whatsoever.

While the stance of the Gulf states on Iran and nuclear issues has been known for many years, the fact that China agreed to include such specific references to Iran in the current statement, unlike its traditional formulations, is interesting. In the present context, when the possibility of renewing the JCPOA with Iran appears unlikely, this may be China’s way of signaling that it views this issue as highly pertinent. The issue of ballistic missile and drone proliferation may hint at Chinese dissatisfaction with Iranian moves in the Russian context. In addition, the subject of securing oil facilities may indicate significant dissatisfaction in China with Iranian attacks against such sites. Such direct reference to Iran is in fact unusual, even if it has been put under less spotlight, and it appears that China is almost blaming Iran for hasty and irresponsible conduct. Iran’s response appeared relatively harsh, but it focused on the islands issue while marginalizing the newer issues – such as terror, nuclear proliferation, ballistic missiles, and drones – which may be more problematic for Iran. The fact that China appeased Iran with the planned visit of Vice Premier Hu Chunhua, who was not promoted at the last Party Congress and is likely to retire soon, is also indicative of China’s approach to the matter.

Still, commentators speculated on a weakening of the “China-Iran-Russia axis,” even if the specific sections on which they based their claims were not totally accurate. Is such weakening indeed evident? First, we must ask whether such an axis exists. From China’s point of view, on the most basic and principled level, it is not part of any axis, but rather constitutes the focal point and the center. Thus in the Party’s resolution on the lessons of history, one of the central conclusions relates directly to the imperative of maintaining Chinese “independence” on both domestic and foreign policy (also based on similar resolutions from the past). China likewise endorses the principle of non-alliance that it declared in 1982, based on lessons from the policy of “relying on one side” (the Soviet Union in the 1950s) and from the Cold War. It is thus clear that despite changes in Chinese foreign policy, alliances and axes are not part of its strategy. “Friendship without limits” with Russia is a nice slogan, but as we know, limits were very much maintained. Furthermore, several months ago the official who may have coined the slogan, then-Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Le Yucheng, who had been considered a leading candidate for the next Foreign Minister of China and who is considered an important expert on Russian issues in the Chinese government, was removed from his position. From Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs he was “demoted” to head of the National Radio and Television Authority – a move that certainly did not portend a strengthening of his status.

If there is an axis in the context of the war in Ukraine that China may seek to join or lead, it is the axis that presumes to be “objective,” which continues to have significant interaction with Russia; an axis in which we may find India, for example. Ad hoc collaborations, insofar as these serve China – with Iran or with Russia – are maintained by China so long as they serve its aims, even if headlines declare that this is an eternal strategic alliance of brotherhood. China will of course continue to increase its trade with Russia as long as Moscow gives it access to cheap energy or other goods at an attractive price, especially when it can do so in yuan and not in dollars. Chinese cooperation with the Gulf states, in this context, is much deeper than that with Iran, especially when Iran is not making moves to enter a framework that would allow China to cooperate with it consistently, actively, and beneficially – i.e., signing the nuclear agreement.

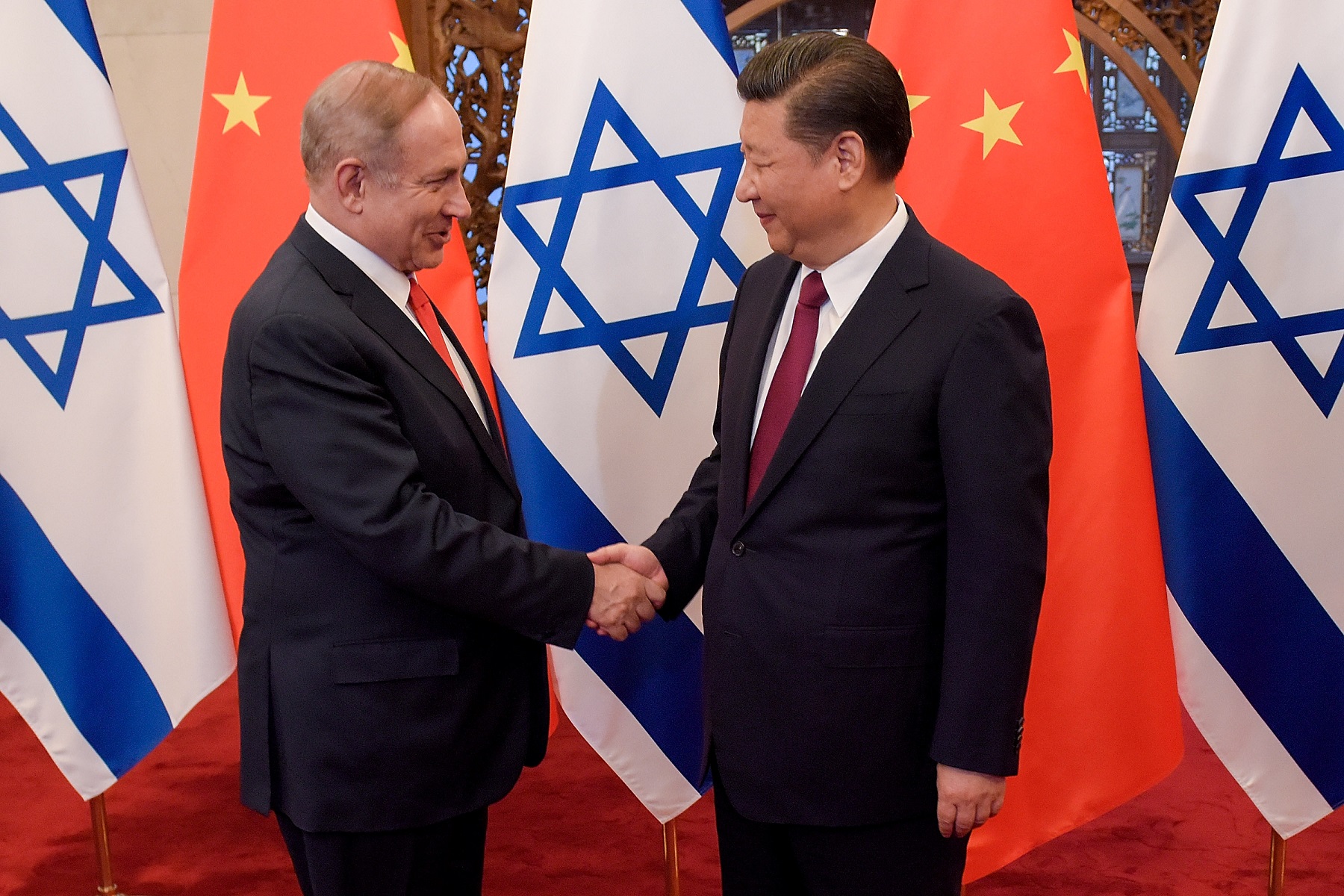

The Israel Connection

It might appear that for Jerusalem, there is an opportunity to leverage Chinese discomfort on Iranian issues and steer it toward Israel’s comfort zone and encourage China to influence Iran. However, such attempts by Israel in the past with Chinese interlocutors were not successful. The common interests for the Gulf states, China, and Israel may help in this context, but there are few grounds for excessive optimism regarding Israeli involvement on the matter. Israel may enjoy the fruits, but it will not be the one to generate them, at least not overtly.

On the other hand, the joint statement does not neglect to mention Israel, just as the previous statements did. In other words, the view that the Abraham Accords removed the Israeli-Palestinian issue from the heart of the regional discourse, at least at the rhetorical level, and in this case in discussions with remote China – is not justified. To be sure, the sections that deal with this matter appear somewhat tempered compared to those of previous statements (for example, they do not mention specific UN resolutions), but they appear in both the joint China-GCC declaration and the joint China-Saudi Arabia statement (and in the latter, they are even more detailed). In the “Report on China-Arab Cooperation in the New Era,” two entire paragraphs are dedicated to the issue, twice as much as for any other “peace” issue in the region (such as Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Sudan, and Libya), with an emphasis on the supreme importance that the Chinese President ascribes to the matter. Even if this is primarily rhetoric, the matter is still far from absent.

Conclusion

China’s presence across the Middle East, and certainly in the Gulf states, has been evident for decades. Over time Beijing has increased its dominance gradually and enlarged the range of states with which it maintains close relations. Xi’s recent visit is thus part of a longstanding strategy, which preceded the declarations of “strategic competition” in the past few years, even if in the present context – after President Biden’s visit in July 2022 to Saudi Arabia and given the somewhat shaky relations between the US and Saudi Arabia – the success of Xi’s visit was also, but not primarily, in scoring diplomatic points.

In the Iranian context, China evinces discontent, both regarding the dead end on the nuclear agreement and on harm to its partnerships and interests in the Gulf. While conveyed primarily as hints, from the Chinese perspective it is a significant signal. Iran, whose domestic situation is sensitive, whether due to domestic or foreign considerations, responded with protest that focused on the Islands issue and diverted attention away from the core points from China’s perspective (nuclear program, weapons proliferation, damage to oil facilities, and so on). This protest was met with diplomatic rhetoric by China, but not at the highest level.

From Israel’s perspective, while it may appear that such a situation generates potential influence on China, including by connecting with the Gulf states on the subjects in which they have mutual interests, such as Iran, it is highly dubious whether such potential can be fulfilled. The fact that China continues regularly to raise the issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, while taking a clear side, and that the subject is raised consistently at various summit meetings and elsewhere, must be taken into account by policymakers in Israel. China’s increased involvement in the region in a variety of fields – in the economy, infrastructure, technology, diplomacy, and more – demands attention, regarding both opportunities and challenges.

Note: Because this article deals primarily with the Chinese perspective, the documents examined are primarily Chinese-language publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment