Alex Hollings

While largely classified Pentagon war games have previously suggested China would succeed in such an attack, a recent series of war games carried out by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think-tank indicates that previous Defense Department war games were likely aimed at identifying weaknesses within Taiwan’s and America’s defensive postures, rather than providing a clear and realistic view of how such a conflict would play out.

But despite the seemingly optimistic outcomes of CSIS’s war games, one thing remained clear throughout every iteration: American intervention on behalf of Taiwan would lead to staggering losses of life and military hardware unlike anything seen by American forces since the Second World War.

And as is so often the case when it comes to Uncle Sam’s combat operations, victory for Taiwan is heavily dependent on the effective use of the full breadth of American airpower — though surprisingly, it’s not the F-22 or F-35 that could make the biggest difference. Instead, it’s America’s bomber force that could win the day.

CSIS played out China’s invasion of Taiwan 24 times, and heavy losses were a constant through all of them

(U.S. Army photo by Thomas Mort)

(U.S. Army photo by Thomas Mort)In a 165-page report released by CSIS, entitled The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan the think-tank outlined the outcomes of 24 wargame scenarios in which China launches a full-scale invasion in 2026. Leveraging the full breadth of unclassified information about each country’s respective military capabilities, stockpiles, and doctrine, the project team played each scenario through the end of the heaviest fighting, and the results were largely positive for those in the West… though positive is a subjective term.

In the one interval played out without any American or allied intervention, Taiwan fell to Chinese forces somewhat rapidly, offering a baseline for the value of Western intervention in maintaining the country’s sovereignty.

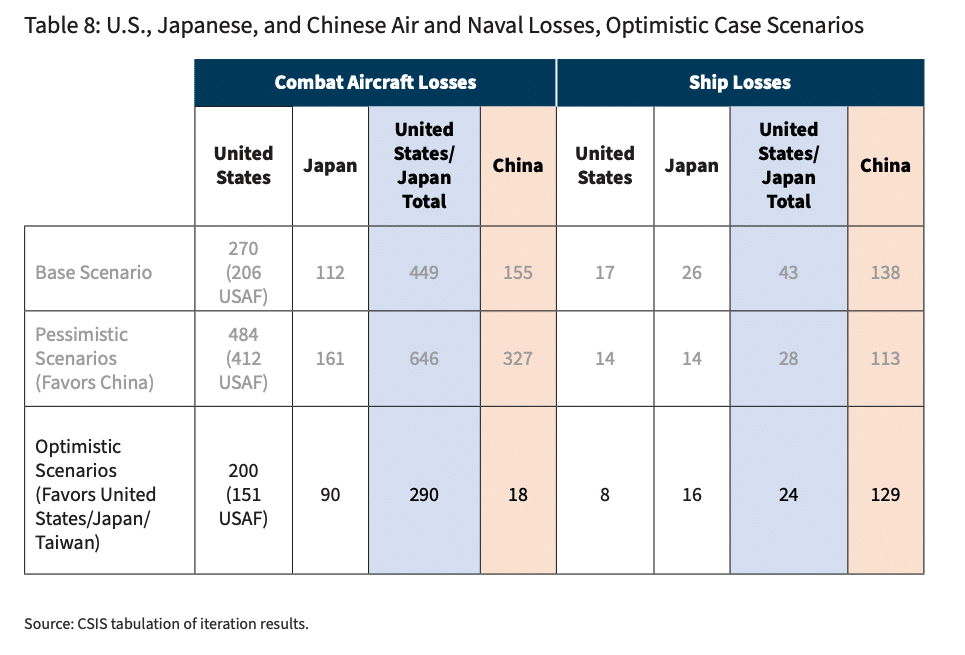

In the handful of scenarios played through with the most optimistic of circumstances, the U.S. and Taiwan secured rapid victories, but with an average of 200 American combat aircraft and eight warships lost, in addition to similar Japanese losses.

In the most realistic “base” scenarios, China was rapidly defeated or fought to a stalemate that would likely ultimately result in Taiwan’s victory, but the average losses for American forces in these iterations included some 270 combat aircraft and 17 warships of varying sorts.

The vast majority of iterations played through were considered “pessimistic scenarios,” in that they included variables meant to hinder American capabilities in ways that potentially could play out in a real conflict.

Even in the pessimistic scenarios, Chinese forces failed to secure a single dominant victory. In three iterations, Taiwan and the U.S. emerged victorious. In seven more, the forces fought to a stalemate that favored Taiwan’s eventual victory. In two others, they fought to a stalemate that favored neither side, and finally, in just three of these pessimistic scenarios, China was able to secure a stalemate that appeared to favor its eventual success.

However, despite that promising list of outcomes, losses for the United States were severe, with a combined average of 484 American combat aircraft lost and 14 U.S. warships destroyed. Once again, Japan also suffered similar losses.

These losses, of course, were relatively small compared to China’s, but because America’s losses usually included two aircraft carriers and many 5th-generation fighters, the personnel and material losses for the United States would be immense and would require years, if not decades, to recover from.

RAGNAROK: For China to take Taiwan, it must negate US AirPower

(U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Keenan Daniels/Released)

After Chinese forces failed to secure a single outright victory in any of the optimistic, baseline, or pessimistic scenarios that included American intervention, the project team established one more set of circumstances meant specifically to identify what it would take for China to succeed. This iteration was dubbed, “Ragnarok” — which is the final battle of the gods and the forces of evil in Norse mythology. Based on their findings, the success of the Chinese invasion is predicated specifically on beating America at what America does best.

“To be victorious, China must negate U.S. airpower, both fighter attack and bombers.”

“The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), January, 2023

Doing so would require a few specific events to play out as needed to benefit the Chinese invasion force, but they’re not entirely unrealistic. First, Japan would need to bar the United States from flying combat operations from their soil, limiting American airfields to Guam where China could concentrate air and missile strikes, wiping out hundreds of aircraft while still on the ground.

This could leave American bombers without viable fighter escorts, opening the door for Chinese fighters to engage them with long-range air-to-air missiles, and limiting their ability to deploy long-range anti-ship cruise missiles toward China’s invasion fleet.

Why are these outcomes so different from previously discussed DoD wargames?

(U.S. Army Military Review)

In 2020, anonymous sources within the Defense Department leaked the results of a series of Pentagon war games in which China repeatedly defeated American forces in the Pacific by 2030. These results were widely publicized and discussed, but like many discussions about military exercises and war games, they often lacked essential context about the nature of such efforts.

It is true that Pentagon war games are conducted behind closed doors to leverage the full breadth of classified intelligence available, which might seem to suggest that these games should be taken more seriously than efforts like this more recent CSIS series, which was based on open-source data. But it’s important to understand the nature and intent of Pentagon war games, and where they differ from objective analysis.

As we’ve discussed in previous coverage around debates surrounding notional training dogfights with high profile platforms like the F-22 Raptor, the goal of these sorts of efforts is not to secure victories and pad a score card, but rather, to specifically place units, leaders, and individual service members in difficult circumstances to assess the very real limitations of current training, equipment, and doctrine. While the goal of each participant is to win, winning isn’t the goal of the enterprise. Learning is.

(DoD photo by Javier Chagoya)

These war games are incredibly important for the leaders, strategists, and planners involved in them, but when it comes to divining what they may mean for real-life conflict from the outside looking in, with only bits and pieces of leaked information to work with, they offer little real value.

This conclusion has now been substantiated by two different war-game revolutions from separate independent think tanks: the aforementioned series from CSIS, and a June 2022 series conducted by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) that indicated neither side could secure a swift victory without incurring massive losses.

However, this does not mean victory over China would be assured, and it certainly doesn’t mean that the United States could rapidly defeat China in a large-scale conventional war in the Pacific of another sort. Instead, these war games offer an insight into the size of the challenge all parties face in such a conflict, and by better understanding those challenges, we can better predict what different parties may do to overcome them.

These types of exercises aren’t meant to soothe or stoke fears. They’re tools that can be used to understand how a fight might play out, with the ultimate goal of using what’s learned to prevent one from starting in the first place.

Because, at the end of the day, warfare is about far more than comparing numbers on paper. But if we’re lucky, we’ll be able to leave it that.

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University.

No comments:

Post a Comment