Much attention has been paid to China’s efforts to modernize its military with new naval vessels, aircraft, nuclear weapons, and other equipment. China has made significant progress on these fronts, but weaponry and equipment are only part of the equation. To successfully project power, countries also need adequate infrastructure and logistics capabilities for deploying troops and equipment. China is currently undertaking a major expansion of its infrastructure that is enhancing its ability to project military power along its western frontier.

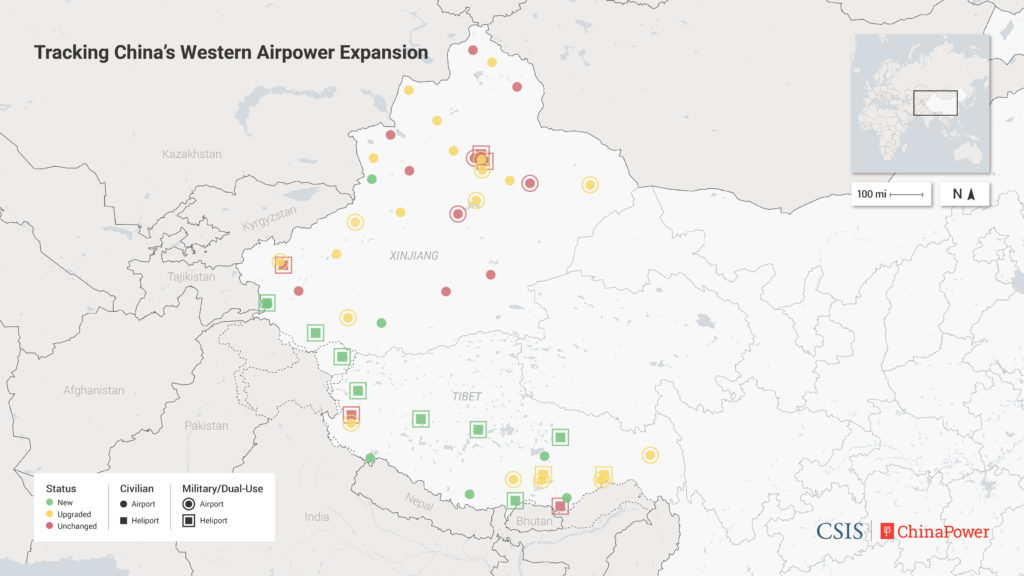

Within its western regions of Tibet and Xinjiang, China is constructing and upgrading dozens of airports and heliports—a large majority of which are military or dual-use facilities.1 China is supplementing its airpower expansion with new roads, rail, and other infrastructure that are upgrading the PLA’s logistics capabilities and enabling more rapid movement of troops, weaponry, and equipment. The pace of development in the region accelerated following standoffs and skirmishes between China and India along disputed portions of their border in 2017 and 2020. China also has growing security and economic interests in neighboring countries in South and Central Asia, as well as concerns about the potential for unrest within its own borders.

Growing Perceived Threats on China’s Western Border

China’s western infrastructure buildup is fueled by perceived external and internal security threats on its frontier. The far-flung regions of Tibet and Xinjiang are of particular concern for China’s leaders. They are expansive in size, together accounting for approximately 30 percent of China’s territory—much of which consists of harsh dessert and mountain terrain. The two regions also border a total of 11 different countries, putting them on the frontlines of China’s relations with its western neighbors.

China perceives significant security threats along its expansive disputed border with India, commonly known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The LAC is roughly divided into three sections. The eastern stretch of the border runs along an area roughly the size of Austria that is claimed by China as part of southern Tibet but administered by India as the state of Arunachal Pradesh. Near the central part of Tibet’s border is a narrow 80-kilometer (km) stretch of land between Nepal and Bhutan that is partly disputed by not just China and India, but also Bhutan. In 2017, tensions flared there on the Doklam Plateau after Chinese army engineers attempted to build a road through the area. India sent troops to stop the construction and China dispatched its own forces to the area resulting in a tense 73-day standoff.

China and India faced off again in 2020, this time at the disputed western sector of the border that straddles the Indian-administered territory of Ladakh, the Chinese-administered region of Aksai Chin, and Tibet. Skirmishes broke out at several points along the LAC in this area—including Galwan Valley, Pangong Lake, and others—resulting in deaths on both sides. This marked the first time in decades that border tensions between China and India resulted in fatalities, and the flashpoint remains a major source of tension between the two countries.

India is not China’s only concern in the region. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is pushing to expand its influence abroad, with significant attention paid to recreating the ancient Silk Road trading networks that webbed from China throughout South and Central Asia and beyond. Xinjiang occupies a central position within the BRI and serves as a key link between China and its western neighbors. China has already emerged as the leading economic player in Central Asia, surpassing even Russia, which had long been the dominant power in the region. China’s security interests have grown in tandem with its expanding economic footprint in neighboring countries. China has beefed up security cooperation with bordering countries—including Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and most recently Kazakhstan—with the aim of enhancing their domestic security and fending off instability that could spill over into China.

As of 2020, China’s Belt and Road Initiative includes 138 countries with a combined GDP of $29 trillion and some 4.6 billion people. Learn more about the BRI and how it will advance China’s interests.

Leaders in Beijing also harbor concerns about internal instability and the potential for separatist activity within Tibet and Xinjiang, both of which are “autonomous regions” with large ethnic minority populations. The Chinese government has put in place draconian policies in Xinjiang to surveil and stifle ethnic minority populations, especially Uyghurs. Beijing is likewise worried about the potential for unrest and separatist activity from Tibetan and other ethnic minorities in Tibet.

Together these perceived threats have compelled China to invest heavily in upgrading the two regions’ infrastructure. New and upgraded airports promise to bring an influx of new business activity and tourism to areas previously disconnected from China’s main commercial and political centers. New roads and rail aim to do the same and facilitate easier movement of people within the regions. At the same time, investments in military and dual-use air facilities afford the PLA a growing menu of options for projecting airpower within the region. New ground infrastructure is likewise rendering remote areas significantly more accessible for Chinese military and security forces, allowing them to project power more easily within Tibet and Xinjiang and potentially into neighboring countries.

China’s Investment in Air Infrastructure

One of the most visible elements of China’s infrastructure investments in Tibet and Xinjiang has been the construction and upgradation of airports and heliports. New and upgraded air facilities significantly enhance the PLA’s ability to move personnel and equipment in the region via air, which is particularly important given the unforgiving terrain of both Xinjiang and Tibet. They also offer the PLA additional platforms from which to launch airborne surveillance and reconnaissance missions, as well as strikes and counterstrikes in the event of a conflict.

The airpower buildup taking place on China’s western frontier is sweeping in scale. Based on analysis of satellite imagery and other open-source material, China Power has identified 37 airports and heliports within Tibet and Xinjiang that have been newly constructed or upgraded since 2017—the year China and India squared off on the Doklam Plateau.2 At least 22 of these are identifiable as military or dual-use facilities or are expected to be once they are completed. The pace of this activity sped up significantly in 2020. That year alone, China began constructing seven new air facilities and initiated upgrades at seven others.

Much of the activity is taking place within Tibet in areas close to China’s disputed border with India. Since 2017, China has initiated upgrades (such as new terminals, hangars, aprons, and runways) at all five of Tibet’s existing airports. All five of these airports are military and civilian dual-use facilities. China is supplementing these with four new airports in Tibet. Three of these—Lhuntse Airport, Ngari-Burang Airport, and Shigatse Tingri Airport—are positioned less than 60 km from the China-India border. The new facilities also fill large gaps along the Indian border where there were previously no airports. If PLA Air Force (PLAAF) units are based at these airports, China will gain several new nodes along the border from which to project airpower into India.3

The PLA is also significantly scaling up its ability to conduct helicopter-based operations through the construction of at least five new heliports in Tibet and the upgrading of two heliports. These heliports, which are operated by PLA Army (PLAA) Aviation units, are dotted throughout Tibet, stretching from Rutog County in the west to Nyingchi City in the east. The addition of these heliports stands to significantly enhance PLA operations in the mountainous region since helicopters are capable of maneuvering in ways that airplanes and ground equipment cannot.

Similar developments are taking place in Xinjiang. At least 15 airports have been upgraded in Xinjiang since 2017, with seven of these being military or dual-use facilities. One such airport is Hotan Airport, a major dual-use airport located approximately 240 km from the western portion of the LAC. At Hotan, a new runway has been constructed along with additional tarmacs, hangars, and other facilities. Less than 5 km southeast of the main airport area, a surface-to-air missile (SAM) complex is being upgraded, enhancing the air defenses at the airport and surrounding areas.

Construction of three new airports has also been initiated in Xinjiang since 2019. In the far western reaches of Xinjiang near China’s borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, China is constructing a new airport at Tashkorgan. The project, which came with a price tag of RMB 1.63 billion ($230 million), is a key part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship component of the BRI. While the airport is likely to serve primarily civilian purposes, there is a new military heliport less than 8 km north of the airport that was completed around 2020.

Despite the military benefits that China’s investments in the region have brought, the PLA faces several notable disadvantages compared to India. Much of China’s side of the border is situated on the highest portions of the Tibetan Plateau, which is often described as the “roof of the world,” owing to its high elevation. Twenty of China’s airports and heliports within Xinjiang and Tibet are located more than 3,000 meters above sea level—far higher than most airports around the world. Nearly all these high-elevation facilities are new or recently upgraded.

The PLA faces major operational challenges associated with operating at such high altitudes. The thinner atmosphere makes it more difficult for aircraft to take off. To account for this, high-altitude airports typically must have much longer runways—a trend that is borne out at many of China’s airports in the region. Tibet’s Qamdo Bamda Airport boasts the world’s longest paved runway, which stretches a staggering 5,500 meters. Shigatse Peace Airport—also in Tibet—features a runway stretching 5,000 meters, tying it for the third longest in the world.

Even with longer runways, airplanes taking off from such high altitudes face significant limitations. Fighter aircraft carrying munitions are typically unable to take off with a full load of fuel, which significantly limits their range. The PLAAF can supplement the range of its aircraft by providing mid-air refueling, but this adds significant logistical complexity and exposes tanker aircraft during a conflict. The harsh and frigid terrain of the Himalayas compounds these issues by making it more challenging to operate and maintain equipment, both in the air and on the ground. The conditions also pose challenges for troops, who require special clothing, equipment, and training to withstand the elements.

Burgeoning Ground and Logistics Networks

China is coupling its expansion of air infrastructure in Tibet and Xinjiang with new roads, rail, and other ground transportation infrastructure. Beijing hopes that by enhancing connectivity within the regions—and better linking them with the rest of China—it can enmesh the two autonomous regions more securely into China’s social and economic fabric. Chinese authorities have also explicitly linked new ground infrastructure to enhancing China’s ability to move strategic and military assets within the two regions.

Tibet and Xinjiang have historically lagged most other parts of China in terms of overall economic development, but especially infrastructure. While the two regions still lag behind their counterparts, economic planners have been pursuing serious efforts to construct roads there, especially in Tibet. According to official figures, Tibet’s highway system grew 51 percent between 2015 and 2020—from 7,840 km to 11,820 km—faster than the growth rate of any other province, region, or municipality. Xinjiang’s network of highways has expanded at a fast clip as well, growing from 17,830 km in 2015 to 20,920 km in 2020.

Many of the new roads and highways being built are connecting major regional hubs to remote areas on China’s borders. In western Xinjiang, for example, China is constructing at least eight roads stretching from the major G219 national highway toward the China-India LAC. The new roads add to a growing network enabling easier and quicker movement of people, goods, and military personnel and supplies close to border areas. Within the military realm, these roads may specifically play a role in moving PLA forces between cities like Hotan—home to a major PLAAF base—into remote parts of disputed areas, such as the Galwan Valley.

Similar efforts are underway at the eastern sector of the border with India. In 2021, China completed construction of a new road and tunnel system connecting the eastern Tibetan city of Nyingchi to Medog County, a remote area that sits directly on the China-India border. The new roads and tunnels reportedly shortened the distance from 346 km to 180 km and cut the travel time by eight hours. This has major implications for China’s ability to project military power directly to the LAC, since Nyingchi is home to the dual-use Nyingchi Mainling Airport, a military heliport, and the headquarters of the PLA’s 52nd and 53rd Combined Light Infantry Brigades.

China has plans to continue building out a more connected network of roads throughout Tibet and Xinjiang in the coming years. China’s national economic blueprint for 2021-2025, the 14th Five Year Plan, lays out a goal of strengthening the construction of “strategic backbone corridors” out of Xinjiang and into Tibet. Among other strategic backbone corridors, it specifically calls for “opening up the G219 and G331 highways along the border [with India] and upgrading the G318 line of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway.”

On top of growing road networks, China is expending significant effort to develop a more robust rail system in its western regions. Xinjiang’s rail network has grown quickly in recent years, from 5,900 km in 2015 to some 7,800 km in 2020. The new lines and stations built throughout Xinjiang have helped to connect many of the major military bases and dual-use airports that dot the region, improving PLA logistics in the region by allowing for easier overland movement of troops, equipment, and supplies.

In Tibet, the sparsely populated mountainous terrain has made it more difficult to construct rail lines. China inaugurated Tibet’s first rail line, known as the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, in 2006, and it has since been expanded. Yet as of 2020 Tibet still had only about 800 km of railway. That is roughly similar to the length of rail in the city of Shanghai, which is approximately 200 times smaller than Tibet in terms of land area.

Yet the situation is changing. In 2021, China opened Tibet’s first high-speed rail line connecting the regional capital Lhasa with Nyingchi. The new line offers the ability to move civilians, as well as PLA troops and equipment, quickly across the eastern portion of Tibet. According to reports, not long after the Lhasa-Nyingchi Railway was opened, it was used to carry new PLA recruits—likely belonging to the 52nd or 53rd Light Combined Arms Brigades—to an exercise field. Officials have openly acknowledged the role that the new railway will play in advancing China’s capabilities in the region. Zhu Weiqun, a senior Communist Party official formerly in charge of Tibet policy, was quoted as saying that, “If a scenario of a crisis happens at the border, the railway can act as a ‘fast track’ for the delivery of strategic materials.”

It is important to note that although this analysis focuses on Tibet and Xinjiang, there are also developments underway in other regions that have significant implications for China’s military capabilities on its western frontier. Tibet and Xinjiang are just two of the seven regions comprising the PLA’s Western Theater Command (WTC), which oversees combat operations and joint training of Chinese military forces throughout China’s western expanse.4 In Qinghai Province, for example, China has been making heavy investments in upgrading military facilities in the city of Golmud, which is a major logistics hub for transporting military supplies into Tibet.

A Close-Up View of China’s Activities along the Indian Border

Zooming in on specific areas generates deeper insight into some of the specific ways China is expanding its military presence on its western frontiers. The sections below utilize commercial satellite imagery to showcase different areas where China is upgrading its military capabilities at various points along the China-India border.

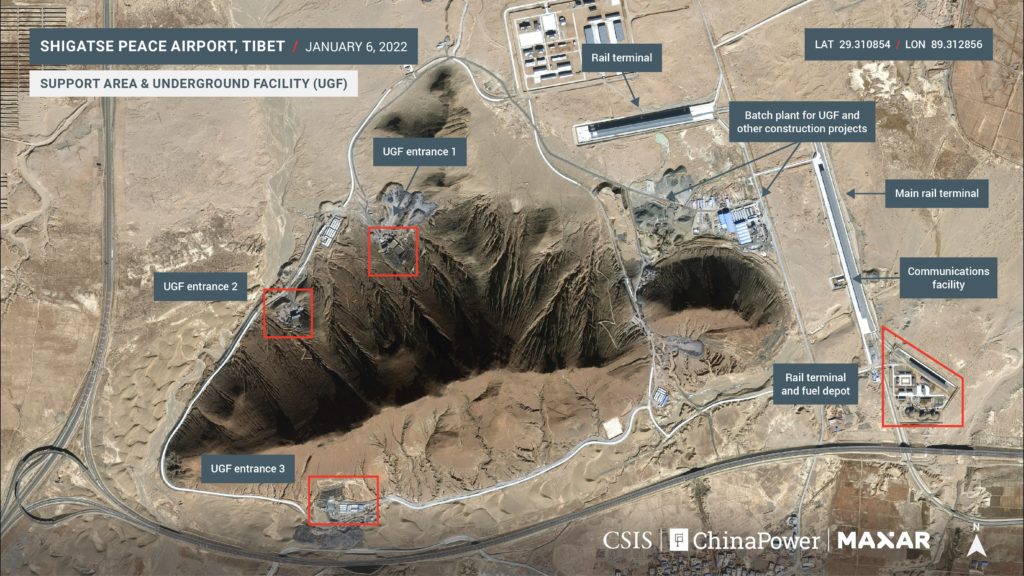

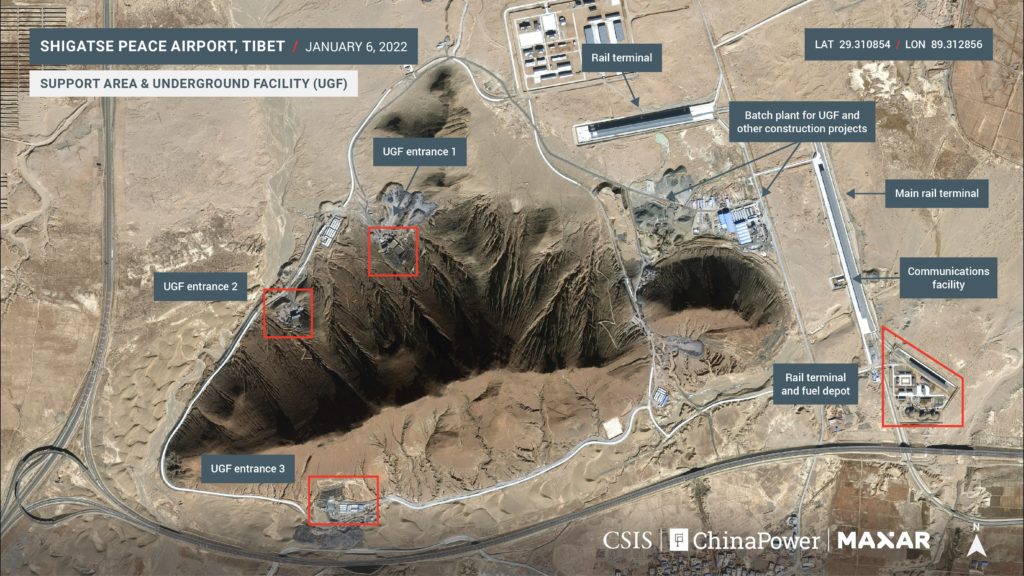

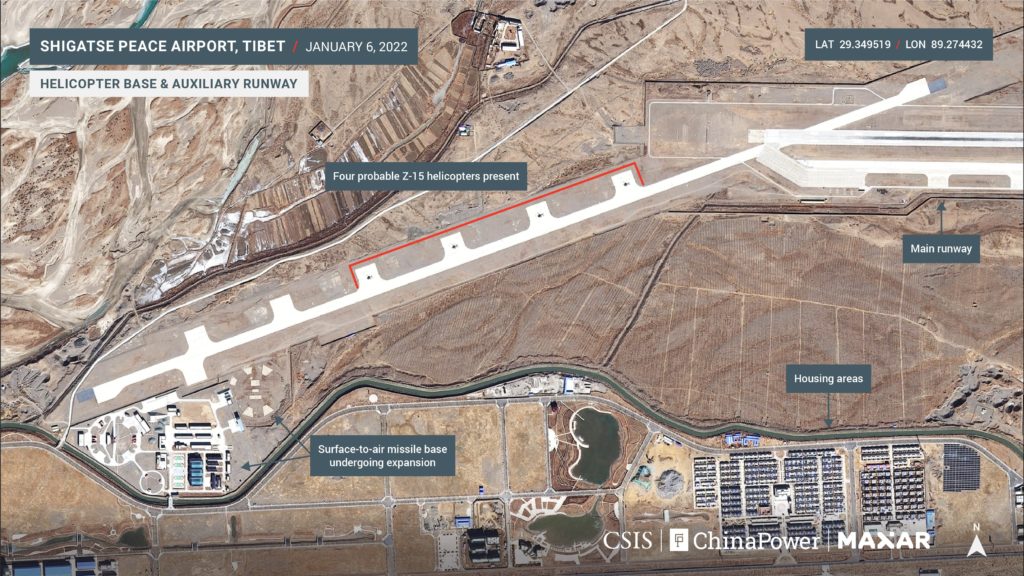

Shigatse Peace Airport

Situated in a valley approximately 155 km north of the China-India border is an important PLAAF base at the dual-use Shigatse Peace Airport. The base is strategically located along the central portion of the China-India border and is closer than any other airport to the disputed Doklam area where the 2017 border standoff occurred.5 The air base typically hosts numerous military assets—including fighter jets, helicopters, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)—capable of launching air attack and reconnaissance missions into neighboring territory.

Both the airport itself and the surrounding infrastructure have undergone major upgrades and expansions in recent years. In 2017, a new 3,000-meterlong auxiliary runway featuring seven helipads was added to the airport’s existing runway. In satellite imagery from January 6, 2022, four helicopters—likely Z-15 medium utility helicopters—are visible on the helipads. 6 At the far western end of the auxiliary runway, an existing SAM base is being significantly renovated and expanded, providing added defense from aerial assaults for the air base and surrounding areas.

The configuration of the new runway is notably different from that of many other airports. Rather than running parallel to the existing runway, the new one intersects the western end of the main runway and runs at an oblique angle. This setup increases the distance between the runways, making it harder for an attacking military to render both runways inoperable without targeting the airfield with multiple precision strikes.

To the east, at the existing portion of the airport, there is a large military presence, and several new upgrades have been made. At the main military terminal and tarmac, 10 probable J-11 multirole fighter jets are present. Three hangars for UAVs have been built, one near the center of the main runway and two at the far eastern portion of the runway. At the runway’s eastern end, a UAV is visible on the tarmac. It is likely a WZ-7 Xianglong (Soaring Dragon), a high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) reconnaissance drone. The WZ-7 has been in service in the PLAAF since at least 2018, and has been spotted at Shigatse and other air bases within the PLA Western Theater Command, including Malan/Uxxaktal Airbase in Xinjiang.

There is also major ongoing construction work at an area approximately 2 km south of the main base and runway. In this area, a new rail line has been built, along with three railway terminals. These terminals appear to be capable of loading and unloading large equipment—including military equipment—onto and off of the railway. Directly adjacent to one of the smaller rail terminals is a new fuel depot, likely used for supplying fuel for the airport and surrounding areas.

Immediately west of the new rail line, work is ongoing at multiple areas to construct a large underground facility (UGF) within a small mountain formation. Imagery shows at least three UGF entrances being built—one each on the north, west, and south sides of the mountain formation. The intended purpose of this UGF is unclear, but the Chinese military has long utilized UGFs as a means of securing and concealing military assets. Over the years, the PLA has been known to house command and control and logistics facilities, nuclear and conventional missile systems, and even strategic naval forces within UGFs.

Capping off work in the area is the construction of a second SAM base approximately one kilometer north of the new rail terminals. This SAM complex is roughly similar in size to the one being renovated at the far end of the new runway, although it appears to be configured for one main launch battery, rather than two launch batteries like the SAM base attached to the auxiliary runway. It is possible that one of the two SAM bases may be intended for ballistic missile defense. Notably, the construction of not just one—but two—air defense bases in the same area suggests the presence of high-value military assets that the PLA wants to protect from attack.

Nyingchi Mainling Airport

Approximately 490 km east of Shigatse Peace Airport lies another major hub of Chinese military power. This site, centered on Nyingchi Mainling Airport, is located just 15 km from China’s border with the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The airport and adjacent garrisons play a role in supporting PLA forces in the area, potentially including elements of the 52nd and 53rd Light Combined Arms Brigades, which are headquartered in Nyingchi.

In recent years, the airport has undergone several upgrades, including expansions of its tarmac, the addition of a new taxiway, and lengthening of its runway. There is also ongoing work on the western portion of the airport bordering the Yarlung Tsangpo River.7 The airport itself appears to primarily facilitate civilian traffic; however, it is immediately connected to large PLAA garrisons and other military facilities and plays a supporting role in providing air transportation for forces in the area. Between 2018 and 2020, the existing PLA garrison facilities immediately south of the airport were upgraded, and an entirely new garrison facility was added.

Immediately adjacent to the new garrison facility, the PLA has constructed a large new motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility, as well as a new complex for training troops. The training facility includes bunkers, trenches, bridges, and various obstacles for practicing maneuvers on foot and in vehicles. In addition to these upgrades, a large SAM base had been constructed on a nearby ledge sitting approximately 50 meters above the surrounding facilities. The proximity of the base to the border suggests that its SAM launchers (known as TELs) can protect not only the immediate airport and garrisons, but also cover areas well into Indian territory.

Finally, satellite imagery of the area provides a bird’s eye view of the aforementioned new high-speed rail line that now connects Lhasa to Nyingchi. The railway and an accompanying new station can be seen perched on the north bank of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, immediately across from the airport and neighboring military facilities. A new road built to support the station provides a direct, short link from the railway to the airport. These additions have transformed the area from a largely remote valley into an increasingly connected transportation hub.

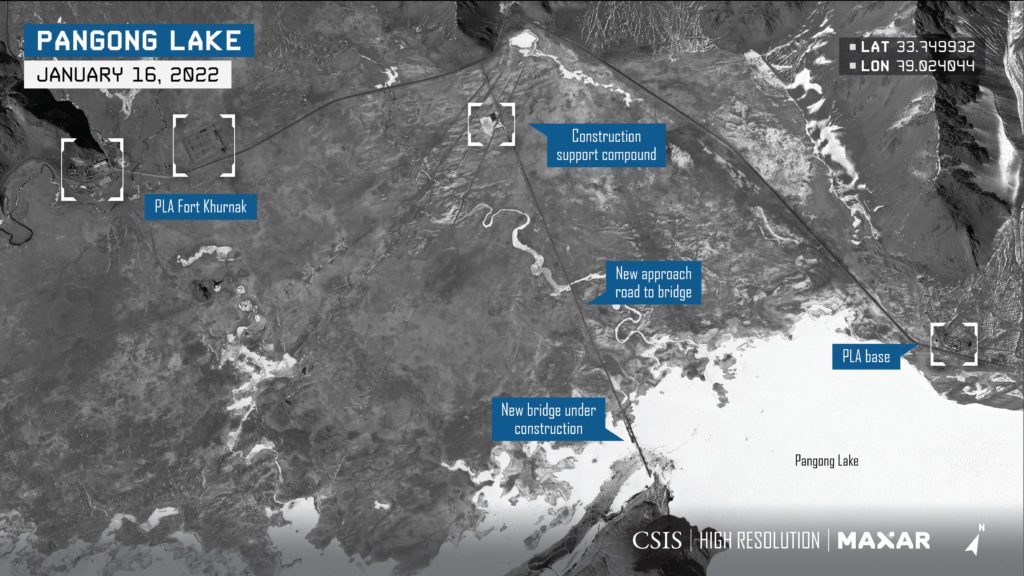

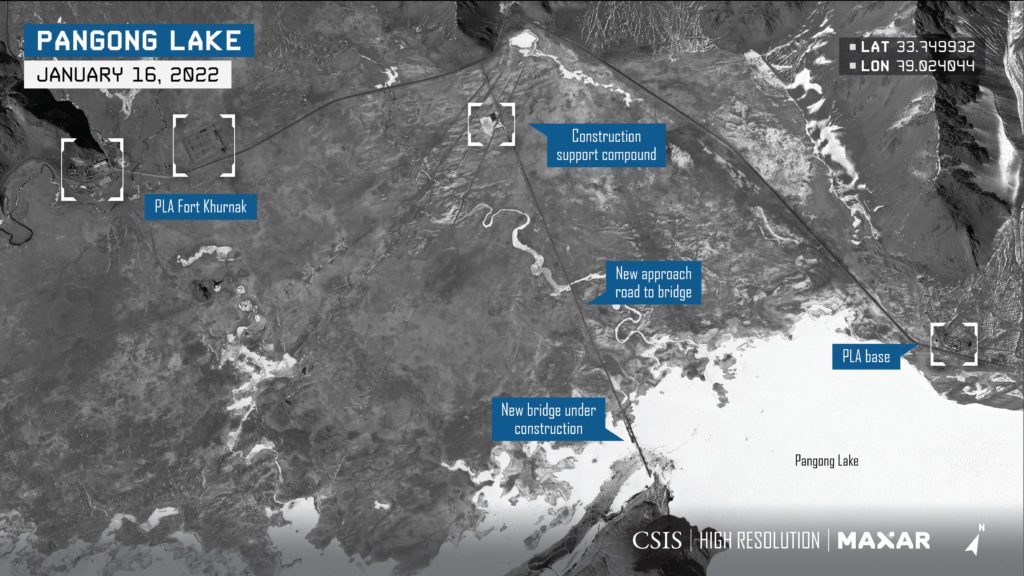

New Bridge over Pangong Lake

China is not just focusing on building airports and related infrastructure. In the wake of the 2020 border clashes between Chinese and Indian troops, both countries have pushed to strengthen their military footholds along key disputed parts of the border. One area of particular concern for China and India is Pangong Lake (also known as Pangong Tso), which stretches some 135 km across the mountainous terrain of northern India, Aksai Chin, and western Tibet. The LAC runs north-south over the lake, splitting it roughly evenly between Chinese and Indian control. Along the northern edge of the lake, Chinese and Indian troops are positioned at dozens of points near the LAC on the mountainous “fingers” that jut out into the lake.

As part of its buildup in the area, China is constructing a new road and bridge over Pangong Lake. The bridge spans one of the narrowest portions of the lake where the north and south banks are divided by roughly 300 meters. Chinese workers began building the bridge around October 2021 and progress has continued despite the brutally cold Himalayan winter. In commercial satellite imagery captured on January 16, 2022, the bridge can be seen nearly reaching the southern shore. Continued work will likely see the bridge completed in the coming months, but workers will still need to connect the bridge with existing routes on the south side of the lake.

Once finished and connected to routes on the south side, the bridge will enable China to deploy troops more quickly to either side of Pangong Lake and to areas closer to the LAC. In the event of a kinetic China-India conflict, the bridge is likely to be targeted for strikes early on; however, during times of peace the bridge will be a major boon to PLA movements in the area. The new bridge will significantly cut the time and distance between Khurnak Fort—a PLA garrison north of the lake—and Chinese military positions near the LAC on the south side of the lake. Reports suggest the bridge could shorten the time between these areas from around 12 hours to approximately three to four hours.

No comments:

Post a Comment