Noah J. Gordon

Climate policy garners the most attention when it is linked to older policy fields that political analysts find more interesting and comprehensible. The focus in recent months has been on how discriminatory tax credits for electric cars made in North America, which constitute a small share of the hundreds of billions of dollars of climate and energy spending in the US’ Inflation Reduction Act, are affecting international relations.

Do Washington’s “Buy American” climate provisions signal the end of free trade as we know it—and will China maintain its lead over the West when it comes to processing critical raw materials? How should European leaders respond given that the United States is currently contributing disproportionately, in terms of military aid, to pushing back a Russian invasion on the EU’s doorstep? And will the EU now change its own policies that have divided member states like France and Germany for decades, for example by relaxing rules on national state aid or jointly borrowing money to pay for green subsidies?

Important questions, to be sure. But these climate measures are primarily important because they make humans pump less greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. It’s worth digging into the major agreements the EU has reached in the few short months since the US signed the IRA into law in August 2022.

Increasing the Price of Pollution

The biggest news here is the tightening of the EU’s carbon market, the Emissions Trading System (ETS). The EU sets a cap on the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by European power plants and industrial facilities like oil refineries, steel works, and chemical plants. These facilities need to buy a permit to cover each ton of emitted carbon dioxide—permits were going for about €85 per ton in December 2022—or pay a fine of €100 per excess ton. Emissions in covered sectors have fallen by 41 percent since the EU introduced its carbon market in 2005; on December 18 the European Council and Parliament reached a deal to cut these emissions by 62 percent on 2005 levels by 2030. Brussels is not merely raising a target here—targets are the New Year’s resolutions of climate policy—but actually reducing the number of permits on the market. The price of polluting will rise; emissions will fall.

Additionally, the EU is extending its existing ETS to cover maritime shipping (from 2024) and establishing a new system to cover buildings and road transport fuels (from 2027). In order to shield low-income households from these new carbon prices, a new Social Climate Fund will spend €86.7 billion from 2026 until 2032. The final months of 2022 also brought intra-EU deals on buildings (all new buildings should be zero-emission buildings by 2030), cars (no new fossil-fueled cars after 2035), and methane emissions.

The EU climate news that got the most coverage was the December 18 deal on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will tax imported goods such as steel, cement, and fertilizer according to their embedded carbon content. Again, this was in part because the deal lends itself to a winners-and-losers analysis along national lines—Russia and China export the highest quantities of covered goods—and because the CBAM is being linked to the trade tensions around the US IRA. However, there is a crucial distinction between the two approaches. The US is openly favoring domestic producers, whereas the EU is phasing out the free carbon permits it gives to its own industry and declining to offer WTO-illegal export rebates to help EU industry break into foreign markets. Therefore, the EU CBAM merely applies the EU’s domestic carbon price to all products purchased by Europeans, wherever they were produced, and does not violate WTO rules against trade discrimination.

Drama vs Bureaucracy

Admittedly, there are other reasons why US climate policy is more suited for international cover pages. The EU’s convoluted, multi-level policy process can leave a reader’s head spinning: the European Commission first presented these carbon market reforms as part of its “Fit for 55” climate package in July 2021, and the December 18, 2022 deal between the European Council and the Parliament is technically still provisional and requires another formal endorsement. The announcement of a provisional agreement on one part of a climate package after a 30-hour negotiation in Brussels the week before Christmas cannot compare to the drama of a kingmaker, coal baron senator doing a U-turn and agreeing to support a giant climate spending package that the US president signs into law a few days later. Who is Hollywood more likely to make a movie about, West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin or the European Parliament’s Dutch CBAM rapporteur, Mohamed Chahim?

The American preference for subsidies rather than regulations also gives newspapers a huge number to put into headlines: the US IRA could direct as much as $800 billion in federal spending to climate and energy projects over the next decade. While the EU’s relatively measly budget doesn’t allow for such large federal subsidies, the permits traded on its carbon market were worth €683 billion in 2021 alone—and the union and its member states are spending more of those revenues on climate action.

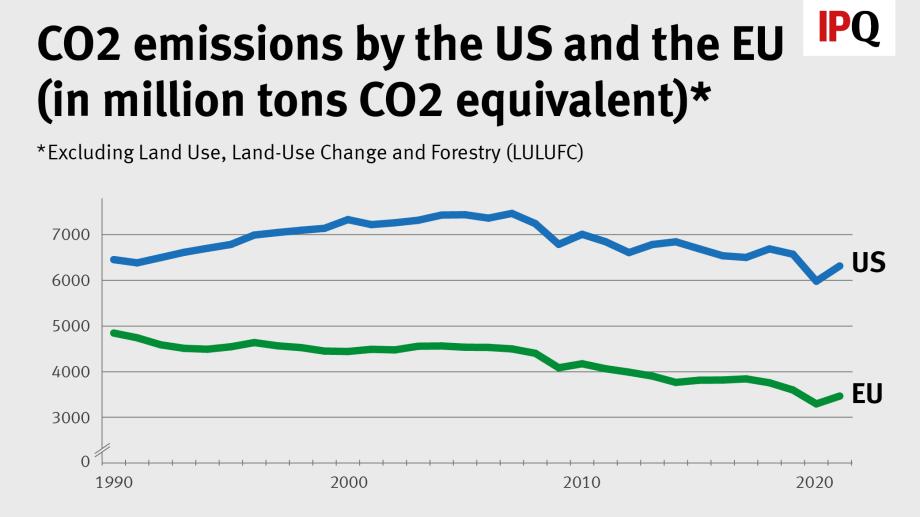

It is easier to track progress in climate policy than it is in most other fields, and plain to see that the European approach has been more successful than the American. According to Climate Action Tracker, EU greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 28 percent between 1990 and 2021. US emissions decreased by just 2 percent over the same period. The figures with dollar or euro signs before them are a means to an end, an end that is even more important than upholding 20th Century trade rules or ensuring good vibes at the French president’s state dinner in Washington, DC.

No comments:

Post a Comment