Jeff Martini, Sean Zeigler and Gian Gentile

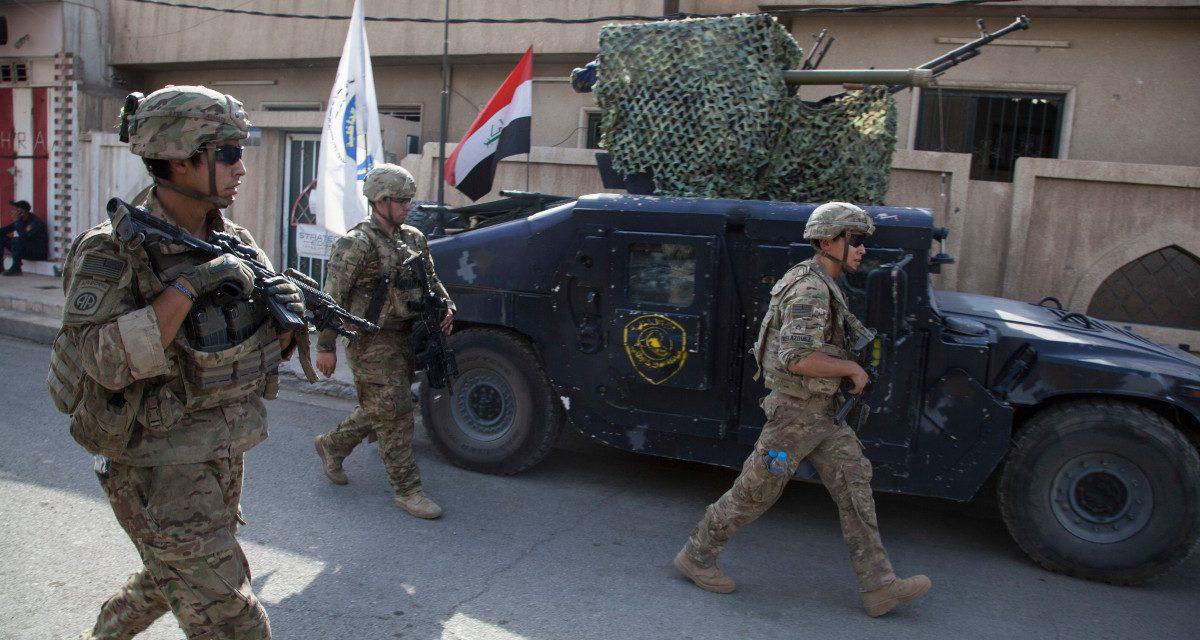

In 2016, as it was pushing ISIS from its Euphrates valley strongholds in Iraq, the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS weighed how best to speed up the military campaign. The coalition ultimately chose to expand its military involvement in support of Iraqi forces, introducing what were described as “enablers” and “accelerants” that would, indeed, prove crucial in dislodging ISIS from Mosul the following year. These contributions are the subject of our newly released operational history of Operation Inherent Resolve. By focusing on US ground forces, the report sheds light on a less appreciated dimension of the fight to defeat ISIS in Iraq. In doing so we challenge the narrative that the concept known as “by, with, and through”—the US military’s reliance on local allies to prosecute ground fighting—does not entail combat by US forces.

Rather, the report demonstrates that defeating ISIS hinged on a ground fight, requiring the grueling liberation of territory kilometer by kilometer. And while Iraqi surrogate forces bore the brunt of frontline fighting, US forces were also engaged in on-the-ground combat operations that hastened the defeat of ISIS. Appreciating such contributions will be necessary to distill the right lessons from an operation like Inherent Resolve, so that we might correctly apply those lessons to future irregular warfare.

A Less than Propitious Start

Beginning in August 2014, through early 2015, the coalition focused on defending Baghdad from ISIS’s advance by generating sufficient Iraqi forces to produce a counterattack. During this early phase of the campaign, coalition forces won back scant ground. Indeed, it took nearly two years from the coalition’s initial military intervention for Iraqi forces to liberate Fallujah, in mid-2016. The slow turning of the tide added to already prevalent doubts that victories in the Euphrates River valley would culminate in a broader expulsion of ISIS from Iraq.

Yet these battles posed fewer operational hurdles than the coming fight along the Tigris, and ultimately the battle to liberate Mosul. For starters, Ramadi and Fallujah are relatively close to Iraq’s capital, which decreased the logistical challenges of sustaining the advance of Iraqi security forces necessary to liberate them. What’s more, the counterattack on Ramadi and Fallujah occurred within federal Iraq, thereby avoiding the political sensitivities associated with transporting federal Iraqi forces through Kurdish-held territory—though this would be required for the coming fight in Mosul. Third, ISIS’s caliphate and center of gravity was in Mosul, not in Ramadi or Fallujah. And finally, in these cities, Iraqi security forces enjoyed an overwhelming correlation of forces in their advantage—at least ten to one—that would be harder to maintain when ISIS presumably massed its remaining fighters in Mosul. So as Iraqi forces liberated Fallujah, there was something to celebrate, but also reason for concern.

Expanding Military Involvement

Faced with the prospect of an already difficult fight up the Tigris that could stall at any moment, the coalition chose to escalate its military involvement. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced new policy decisions, including the use of US Army artillery regiments and Apache squadrons to attrit ISIS prior to the advance of Iraqi security forces, as well as allowing US Army advisors to engage with Iraqi counterparts closer to the front line and at lower echelons. US military commanders subsequently built on these policy choices by issuing a tactical directive lowering the target engagement authority to speed up the strike process. Taken together, these steps expanded the role of US ground forces in the fight and accelerated the defeat of ISIS.

These accelerants were first noticeable in the series of operations that the Department of Defense described as “setting the conditions for Mosul.” The operational mission was to seize key terrain south and east of Mosul that could eventually be used to advance on the city. Unlike Ramadi and Fallujah, where the objective was to liberate the respective population centers, setting the conditions for Mosul entailed seizing roads, establishing bridge crossings, and generating firing positions and assembly areas for an eventual assault on Iraq’s second-largest city and the capital of ISIS’s self-proclaimed caliphate. US Apache squadrons conducting close combat attack were crucial to these operations, attriting ISIS forces on the west bank of the Tigris, thus enabling Iraqi security forces to maneuver through what was considered the teeth of ISIS defenses. This operation culminated in the seizure of Qayyarah West airfield, which is within artillery range of Mosul.

Once the urban fight for Mosul began, the changes in authority introduced by the overall operational commander General Stephen Townsend, alongside input from his land component commander General Joseph Martin, were significant in accelerating the speed of operations. These changes empowered field-grade officers to approve certain strikes—an authority previously held at the one-star level. That authority was made even more significant by allowing US advisors to move closer to the front lines, so they could help coordinate the delivery of joint fires. Indeed, during the Mosul operation, some US advisors were authorized to move as close as the last covered and concealed position before the front line. In the interviews we conducted with US military personnel, a common interpretation was that these changes not only provided tactical advantages but also strengthened Iraqis’ resolve by demonstrating higher levels of US commitment to the fight.

Sorting the Lessons

Our operational history details these ground force contributions, concluding they were crucial to the defeat of ISIS, which, prior to their introduction, appeared far from assured. A broadly generalizable lesson from Inherent Resolve, we argue, is that policymakers need to understand that “by, with, and through” does not obviate the need for direct combat by US forces. Even for advisors, their ability to deliver fires is often crucial to their effectiveness with their counterparts. Thus, it is more accurate to think of “by, with, and through” as buying down the risk to US personnel, not eliminating that risk altogether.

In analyzing the portability of Inherent Resolve to future contingencies, we urge caution in applying lessons too literally. One of the defining features of the operation was the degree to which US forces had prior experience in country after the 2003 US invasion, and the degree to which the United States had built a kernel of capability—in this case, the Iraqi Counterterrorism Service being the exemplar—that it could lean on. Furthermore, the operation pitted a state actor against a protostate with weak military capabilities and rudimentary command-and-control attributes. Combined, those are relatively rare circumstances. The success of Inherent Resolve will not be easily replicated in other contexts.

Jeff Martini and Sean Zeigler are senior researchers at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation, as is Gian Gentile, in addition to serving as the associate director of the RAND Arroyo research center. All three served as project leaders on the study from which this article is drawn.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

No comments:

Post a Comment