Summary

China is taking measures to support its property market, so declines are likely to ease—and even if they don’t, we’re not looking at a subprime crisis.

China is taking measures to support its property market, so declines are likely to ease—and even if they don’t, we’re not looking at a subprime crisis.

A proactive Chinese invasion of Taiwan is a low-probability event in our view, at least over the near to medium term. But should it happen, the impact would be high.

From China’s perspective, the costs of invading Taiwan could be economically catastrophic, with potential global sanctions and isolation setting China back a couple of decades.

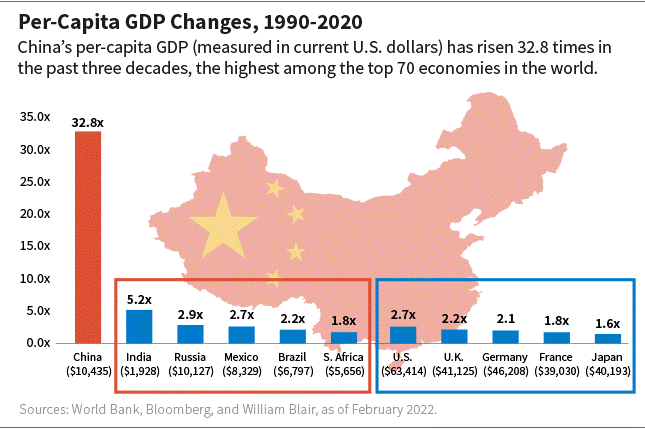

China’s future growth is uncertain amid risks stemming from domestic issues (structural, economic, and societal), increased tensions with the United States, and deglobalization. And that has investors wondering about the outlook for Chinese equities. Here are the top five questions investors ask us—and how we respond.

How does China’s COVID response affect your investment thesis?

In the near term, China’s COVID response is negative for our investment thesis because it has adversely affected consumer and business sentiment as well as economic activity across segments (including retail, property, manufacturing, and supply chain). I estimate that nearly 70% of China’s recent slowdown is attributable to its COVID management.

The unemployment rate—particularly among younger people—has increased. This is partly due to the impact of COVID lockdowns on the overall economy (in particular the service industry) and partly due to reduced employment opportunities in the internet industry amid recently increased regulations.

The lockdowns obviously limit consumers’ physical ability to get to stores and restaurants and to travel, but the psychological impact from uncertainty around lockdowns is even more severe and likely to be long-lasting. No one knows which city will be locked down next and for how long, and when people have no confidence around the near future, they tend to hunker down and wait. It’s therefore not surprising that the household savings rate in China surged to as high as 40% this year from an average of 25% to 30% in prior years (which is high to start with).

China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth will probably be down around 3% this year, and in China, that’s the equivalent of a recession. To address the material slowdown of the economy, the Chinese government may have to seek a more effective balance between its COVID policies and economic growth.

We expect China to continue pursuing its “dynamic zero-COVID” policy in the near term, with increased focus on targeted and shorter lockdowns, if needed to reduce the adverse impact on the economy. We may get a clearer understanding of the COVID policy outlook now that the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has ended. Before an event like this, the CCP tends to take a very conservative approach to managing society; after, there could be more likelihood of change.

China has also gradually relaxed the quarantine requirements for international entries to the mainland to 7+3, which refers to seven days of mandatory quarantine in designated hotels plus three days of self-quarantine at home (previously, it was 14+7).

Hong Kong, meanwhile, has recently removed mandatory hotel quarantine requirements completely (previously seven days), and now only requires three days of at-home self-quarantine. The success of Hong Kong’s new quarantine policy could pave the way for China’s further relaxation of entry requirement for the mainland.

My conclusion: China’s COVID situation and related policies have negatively impacted the Chinese economy and equities, but we expect a marginally and gradually improved policy going forward. This could help Chinese equities, in my opinion.

Is China experiencing a real-estate crisis?

The Chinese property market has been going through a structural deceleration-to-decline phase since the mid-2010s, and in 2022, it experienced an even larger-than-expected decline, exacerbated by COVID lockdowns.

China’s property market bubble became acutely evident nearly 10 years ago, reflecting inflated property prices, excessive investments, and low affordability. The Chinese government has since taken measures to address the problem by constraining both supply and demand. For example, land sales by local governments and new home developments have been limited. First-time homebuyers must generally make a 40% down payment, and other homebuyers are not allowed mortgage financing. These measures have effectively cooled China’s property market in recent years, resulting in an overall flat to slightly down market.

COVID lockdowns exacerbated the property market decline this year, halting purchase and construction activities and materially reducing confidence among homebuyers. As a result, new home sales in many major cities were down 40% to 50% year-over-year in recent years. This is concerning, as it led to a material slowdown of the overall economy (because the property market directly and indirectly impacts 20% to 25% of the Chinese economy.)

As dire as that sounds, this may not lead to a credit crisis like the one that occurred in the United States in 2007 and 2008, because the Chinese housing market is mostly cash-based. Among first-time homeowners, the only eligible mortgage applicants, mortgage penetration is also quite low, at less than 30% (and an average 40% down payment).

In response to the situation, the Chinese government is engaged in a balancing act. The property market is at the epicenter of many industries in China, from construction to infrastructure to consumer spending (because there’s a wealth effect). As a result, the Chinese government recently announced measures to support property markets, though it does not want to boost the market too much and risk exacerbating the structural issues.

For example, local governments of more than 20 cities recently enacted a stimulus policy that allows mortgages for all homebuyers (and 20% down payments for first-time homebuyers). The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has also lowered the five-year prime loan rate (which drives mortgage rates) three times in the last 12 months—by 5 basis points (bps), then 15 bps, then 15 bps again.

My conclusion: China is taking measures to support its property market, so declines are likely to ease—and even if they don’t, we’re not looking at a subprime crisis.

What geopolitical concerns should investors consider regarding China (including Taiwan)?

In my opinion, the No. 1 geopolitical concern regarding China is U.S-China relations, which are entering a new phase—one in which the nations are strategic competitors. Everything else stems from that.

As background, there is the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which we all know as China, and the Republic of China (ROC), which we all know as Taiwan. The two separate China regimes, and the current China-Taiwan issue, were a legacy issue resulting from the Chinese civil war, which ended in 1949. At that time, the ROC lost control of mainland China to the PRC, but Taiwan remained under the ROC’s governance. However, in China’s view, there is only one China, and the PRC is the legitimate representative of China.

However, there has been significant ambiguity when it comes to U.S. relations with both China and Taiwan over the decades. For example, in 1979, the United States established diplomatic relations with the PRC, recognizing it as the sole legitimate government of China. At the same time, U.S. Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act, which does not guarantee that the United States will intervene militarily if the PRC attacks or invades Taiwan. However, the United States has continued selling weapons to Taiwan.

For China, Taiwan remains the biggest unresolved sovereignty issue. Its official stance toward Taiwan has been that Taiwan is a part of China; China will pursue peaceful reunification and “one country, two systems” with Taiwan; but China does not commit to abandoning the military option if Taiwan declares independence or foreign forces meddle with the situation.

China, Taiwan, and the United States have maintained the status quo over the past few decades, but it gets challenged from time to time, particularly when U.S.-China relations get tense (as they did when Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan recently). China usually responds with military drills in public waters around Taiwan (because going into Taiwanese waters would be an invasion).

Further supporting the status quo is the enormous cost of a potential military conflict to all parties involved.

From China’s perspective, the costs of invading Taiwan could be economically catastrophic, with potential global sanctions and isolation setting China back a couple of decades. Such an invasion could also be devastating to China’s image and stance in the global community (China places considerable cultural importance on “face” and aspires to leadership in the global community). Lastly, an invasion could also threaten China’s own societal stability, because a potentially unsuccessful military campaign combined with global sanctions and isolation could easily lead to social unrest.

In summary, I believe the probability of China proactively invading Taiwan is low, especially in the near to medium term, given the high costs mentioned above. However, China could react to provocations that threaten and disrupt the status quo.

From the United States’ and Taiwan’s perspective, the costs of upsetting the status quo could have a material impact on Taiwanese and related global semiconductor supply chain. It could also lead to potential instability across the Asia-Pacific region.

My conclusion: A proactive Chinese invasion of Taiwan is a low-probability event in our view, at least in the near to medium term. But should it happen, the impact would be high, so we need to closely monitor the development.

You mentioned supply chains earlier. How is the move toward deglobalization affecting China? And how do you see it playing out?

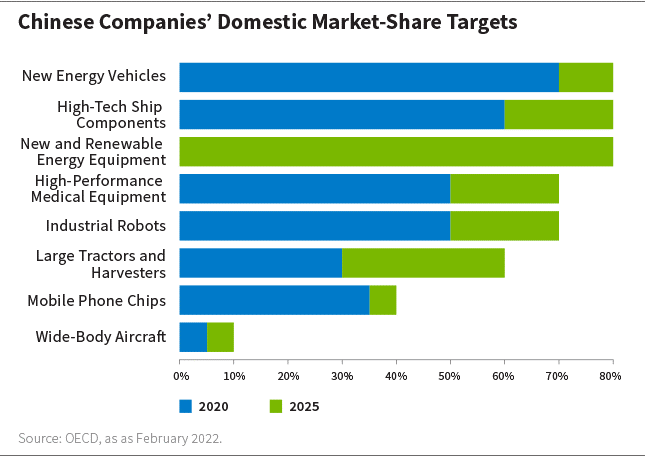

Some supply chains left China before the current deglobalization trend began. China used to be the global textile manufacturing center, with major retailers such as Walmart and Target sourcing from the country. But that supply chain started moving to Vietnam and Bangladesh nearly 10 years ago—partly because China was no longer the cheapest producer, partly because China’s currency strengthened, and partly because China began focusing on higher-tech industries with less environmental impact.

However, in response to increased deglobalization trends, rising geopolitical risks, and recent COVID disruptions, global companies have started to diversify their supply chains and reduce their dependence on one country (such as China). Even Chinese companies have started to expand their capacity and supply outside of the mainland—in Indonesia, Vietnam, Mexico, and Eastern Europe—in order to better serve overseas demand.

For example, Apple (including its suppliers in China) started to develop new supply chain and manufacturing capacity outside of its key supply country, China, by building capacity in Vietnam and India. However, China remains Apple’s largest supplier, with 60% to 90% of Apple components and final products manufactured in China.

China’s large and skilled labor force; competitive cost structure; large-scale, advanced infrastructure and technology capabilities; and supportive business environment remain attractive to global companies from a fundamental perspective. Therefore, I believe deglobalization’s impact on the supply chain shift could be moderate in the near term, and the long-term evolution could be gradual.

My conclusion: China’s role in supply chains is changing, in part because of a natural evolution and in part because of geopolitical considerations. This will affect China, because 20% of its GDP comes from gross exports. This will also affect global supply chains and related global industries that still heavily rely on China. However, I think the trend and effect will both evolve gradually over time. And I don’t believe China’s goal of further opening up to the world and moving up the value chain changes.

Should investors be concerned that Chinese companies’ U.S.-listed shares will be delisted from exchanges?

At the end of 2020, with U.S.-China relations worsening, the United States passed a law stating that any company listed in the United States must be auditable by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB).

China was one of a few countries with large American depository receipts (ADR) listings that could not do so (because of different jurisdictions and laws). Many market participants thought China wouldn’t yield, but I had a different view, and was right—China decided to let the PCAOB come and audit those companies.

Following a series of negotiations between regulators and delays driven by COVID travel restrictions, there is a prospective solution currently being tested by U.S. auditors in Hong Kong. Thus far, China has complied with requests for sample data including some of its largest U.S.-listed companies. A determination from the PCAOB is expected by the end of the year, and China has three years from the passing of the 2020 law to be fully compliant.

My conclusion: China has demonstrated its pragmatic stance to the ADR issue, with the goal of keeping those companies listed globally. I therefore expect it will allow PCAOB auditing to move forward—and with that will come less risk of delisting.

Five Takeaways

Despite China’s uncertain future growth, I think there is reason to be cautiously optimistic. To recap, here are the five key takeaways.China’s zero-COVID policy has been bad for Chinese equities but could marginally improve.

China is taking measures to support its property market, so declines are likely to ease—and even if they don’t, we’re not looking at a subprime crisis.

A Chinese invasion of Taiwan is a low-probability, high-impact event.

China’s role in global supply chains is changing, and this may hurt in the near term, but China’s goal of further opening up to the world and moving up the value chain likely doesn’t change.

China wants its companies listed globally, so will allow auditing to move forward, and with that should come less risk of delisting.

:quality(100):focal(2380x1100:2390x1110)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/4FNDQF7NZ5BN3GENMQ3HLDUR6I.jpg)