Maggie Smith and Teddy MacDonald

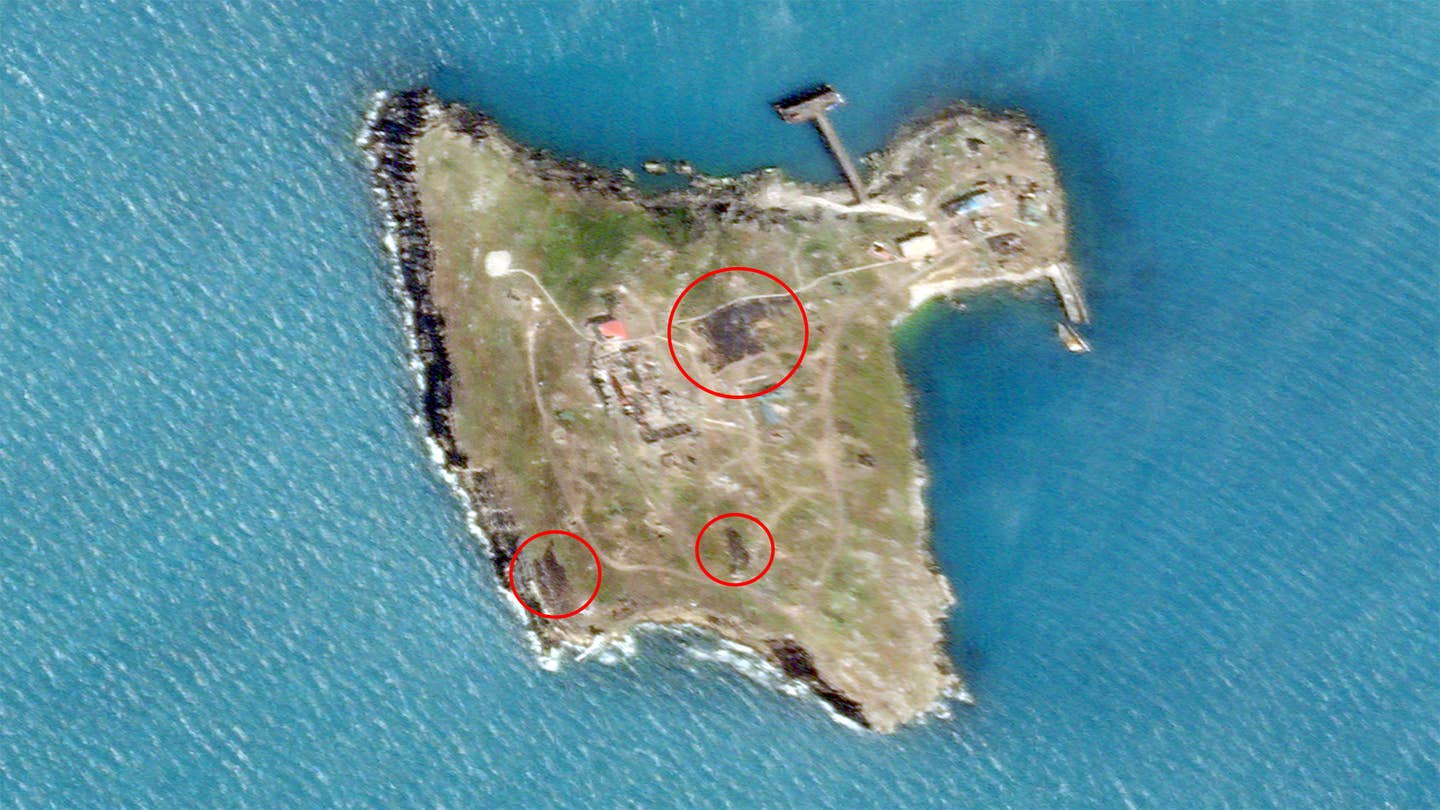

On November 27, 2020, Iran’s top nuclear scientist was assassinated. The initial accounts differed wildly, and it took roughly ten months for the New York Times to break the real story. In prose that could have come from a sci-fi novel, the world learned that Israeli intelligence operatives had carried out the assassination with “a high-tech, computerized sharpshooter [rifle] kitted out with artificial intelligence and multiple-camera eyes, operated via satellite and capable of firing 600 rounds a minute.” A more salient, tactical manifestation of autonomous capabilities is drone warfare. Particularly lethal is the American-made, multipurpose, loitering munition Altius 600 that has a range of 276 miles and can operate at a ceiling of twenty-five thousand feet, providing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, counter–unmanned aircraft systems effects, and precision-strike capabilities against ground targets. Many systems like the Altius “will use artificial intelligence to operate with increasing autonomy in the coming years.” But AI-enabled weapons systems are already being used for lethal targeting—for example, the Israeli-made Orbiter 1K unmanned aircraft system, a loitering munition recently used by the Azerbaijani military in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, independently scans an area and automatically detects and destroys stationary or moving targets kamikaze-style. If the Orbiter 1K does not observe a target right away, it will loiter above the battlespace and wait until it does. As two instances of AI-augmented, autonomous weapons being used to kill remotely, the assassination and the drone warfare of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War draw attention to longstanding concerns about AI-enabled machines and warfare.

Importantly, for the United States to retain its technological edge, it must prioritize AI investment and military modernization by focusing on the development of artificial intelligence and derivative technologies to secure the large, enterprise-sized, and distributed networks relied on for all warfighting functions and to the maintain tactical and strategic advantage in the current competitive environment. However, modernization must also be thoughtful and purposeful to allow for a careful consideration of the ethical and moral questions related to using autonomous systems and AI-enabled technologies in lethal military targeting. Military ethics naturally evolve alongside military technology and, as weapons and their effects become better understood with use and time, ethical considerations are revised and updated. But with AI-enabled battlefield technology, we should engage in discussions about morals and ethics before employment, and continue those discussions in parallel to the development, testing, adoption, and use of AI-enabled weapons systems. Even though a breakthrough in AI by any adversary is an existential threat to national security—and a breakthrough by the United States will likely save American lives on the battlefield—any premature adoption of such technologies in warfare presents an equally dangerous threat to our national values. However, short-term risk avoidance is really long-term risk-seeking behavior, which will result in our adversaries eventually outpacing the United States and achieving technological overmatch.

Roots of Concern

Today’s AI is rooted in machine learning (ML) and is nearly ubiquitous, impacting how we live, work, interact, and make decisions. Beyond the battlefield, technological advancements driven by AI are having similar impacts, both large and small, on society, disrupting how we work and live in tangible ways and changing the nature of relationships across and between people and institutions. Disruptions are occurring at an increasing rate, prompting us to reconceptualize and update how we think about work, the labor force, investments in time, resources, manpower, and policies to adapt to the new reality of technology in the twenty-first century and its implications for the modern world order.

Presently, human interaction with ML-based AI is limited. A human writes the algorithm designed to execute a specific task and is then removed from the system, allowing the AI to receive data feedback, change its behavior based on that feedback, and gradually become more efficient at the original, human-assigned task. Critical to the learning process is access to large data pools (the more data available, the better, more quickly, and more robustly the AI is optimized), which are becoming commonplace as people adopt an internet-of-things way of life and use the internet to access services and information. Some simple examples of ML-based AI include purchasing recommendations on Amazon or movie recommendations on Netflix—recommendations based on a user’s previous behavior on the respective platform or service. Tesla’s autonomous driving is another example—the autonomous system receives a steady data stream from its vehicles to continually learn about roads and driving behaviors to optimize the autonomous driving system.

Different Futures

But as the autonomous systems revolution unfolds, there is divergence in how ML-based AI is perceived and in predictions about the technology’s future. One perspective is rooted in optimism, offering a utopian future in which AI benefits humankind and has a net-positive impact. Jobs will be created; catastrophes such as climate change and nuclear holocaust will be averted; and humans will be better able to self-actualize. The alternative perspective envisions a dystopian future in which AI takes over but lacks the ability to understand humanity and therefore wreaks havoc on humankind and society. Predictions that account for Moore’s Law increase the complexity of how AI could shape the future: as processors reach the atomic level, experts speculate that exponential growth in processing power may end, thereby creating a physical limit that will prevent AI from reaching singularity—or the time when the abilities of a computer overtake the abilities of the human brain. And even though quantum computing holds potential for AI, and may bridge the current theoretical limits on processing, unknowns abound.

Specifically, there are two key areas of concern—especially for the implementation of AI-powered technologies on the battlefield: AI development and AI implementation. Namely, it is unclear if developers should wait for a notionally perfect, safe solution before implementing AI technology, or if they should introduce AI technology after it reaches an acceptable level of proficiency and allow it to organically develop in the wild. For example, the several companies pursuing autonomous driving technology are understandably cautious, and some remain unwilling to make their technology available for public or widespread use. The hesitancy is, in part, related to a desire to avoid fatal accidents and a fear of being held liable for mistakes made by an immature technology.

However, a few companies, most notably Tesla, are more eager to take their autonomous driving technology public and seek rapid AI employment. Tesla is willing to accept risk and chooses to rely on iteration and data amalgamation with the expectation that the company’s cars will drive better over time, as they accrue experience in real environments with real hazards. Supporting Tesla’s approach of rapid implementation, some experts say that most of the difficult development work on AI has been done, so now it is up to businesses to incorporate AI into their products and strategies to push the technology forward. But adopting new technology is never easy—especially when the new technology is likely to change the character of warfare and be used to kill.

Robots and Warfare

The use of autonomous systems and AI in warfare and military operations is understandably provocative: on the one hand, autonomous and AI-enabled systems save friendly-force lives by keeping troops physically removed from the battlefield, and on the other hand, their use raises ethical and moral questions about targeting, positively identifying, and executing lethal-force missions from thousands of miles away. Critically, researchers argue, “if humans increasingly leverage AI to inform, derive, and justify decisions, it also becomes important to quantify when, how, and why and under which conditions they tend to overly trust or mistrust those systems.” Their point is especially salient for the military-use cases because there are incongruities between control and responsibility when control of an autonomous system has become so distributed (i.e., spread across multiple actors—both nonhuman and human) that it is unclear which party or system is to blame for a mistake. On a battlefield, mistakes can result in fatal consequences—like the killing of Afghan civilians—and, if an autonomous system determines positive identification of an enemy target and signals to its operator to fire, the larger question is if the human operator will ever question the computer’s information.

Currently, most existing AI technologies are not fully autonomous and are instead implemented to augment human decision-making. Decision-assistance tools seek to improve upon a human’s capacity to interact with, assess, and draw inferences from large amounts of information. The Department of Defense’s push to develop the Joint All-Domain Command and Control system that will aggregate data from the thousands of military sensors deployed around the globe is an example of an AI-enhanced decision-making tool intended to unify battlefield information for better outcomes. Because users of decision-assistance tools interact with the AI by incorporating the technology into their processes and procedures, it is difficult to assign blame when something goes wrong. Notably, by “inserting a layer of inscrutable, unintuitive, and statistically derived code in between a human decisionmaker and the consequences of her decisions, AI disrupts our typical understanding of responsibility for choices gone wrong.” Humans tend to like things that are explainable, but AI and ML algorithms are often unexplainable either due to secrecy, a lack of transparency, or a general lack of technical expertise.

Algorithms, because of their “inscrutability” and “nonintuitiveness,” prevent humans from evaluating them to assess their effectiveness or veracity. If a model is not understandable through human intuition, it is also inscrutable, making it difficult to determine when or how a mistake or mishap occurs. For example, causal relationships are prone to be highly complex and nonintuitive, especially relationships that deal with human behavior. If we account for all the factors that influence a single human action, we quickly realize that many actions are the result of factors that defy human intuition—not every action is rational. AI-generated conclusions are subject to the same opaque processes—machine-derived causal relationships are subject to opaque correlations that defy human comprehension.

In the August 29, 2021, US drone strike that mistakenly killed ten Afghan civilians just days after a suicide bomber killed thirteen US service members and 169 Afghans at the Kabul airport, an independent investigation determined no violation of law, including the law of war. United States Air Force Lieutenant General Sami D. Said stated that the individuals involved “truly believed at the time that they were targeting an imminent threat to U.S. forces” and that, “regrettably, the interpretation or the correlation of the intelligence to what was being perceived at the time, in real time, was inaccurate.” Add the confusion of the ongoing force withdrawal from Afghanistan, the emotional response to the loss of American lives, and the chaos of the information environment, and a thick fog of war quickly blankets all operations. Human decision-making on the battlefield is complicated and must account for a variety of unstable factors, to include emotional factors, and defaulting to an AI-informed decision is likely in the chaotic seconds before authorizing an attack—the time to question an opaque, algorithm-derived decision or data for accuracy simply does not exist in warfare.

Social Changes

Another strategic national security concern is how the adoption of AI and automation is changing society. How data and technology are used, and to what ends, raise questions about privacy, data protection, and civil liberties. As companies and governments generate, seek out, and collect increasingly large pools of data, concerns over AI and how data is used, maintained, and shared are also increasing. Technology companies that accumulate data will seek to protect and even expand their ability to collect information on users if they remain incentivized by advertisement dollars to configure information feeds to keep users on their sites or applications for longer periods of time. And, even while American society is considered the vanguard of individual liberties, as AI employment continues, more algorithms will gain access to individual data and threaten our traditional understanding of privacy.

From a consumer marketing perspective, AI allows companies to know what their customers want before they even search for an item, relying on purchase and search engine history to curate recommendations that nudge consumers toward products that are likely to catch their eyes. Big data coupled with online shopping has enabled microtargeting at a low cost, changing how companies engage with consumers and how people shop for goods. The use of AI to monitor and track all sorts of daily activities is also concerning from a privacy perspective—from fitness trackers to shopping habits, data is generated by individuals constantly. However, limiting or preventing data collection will stymie growth and limit the potential of AI because the technology requires tons of data to mature and evolve. While hotly debated, concerns over data privacy and protection have equally concerning implications for America’s position as a global technology leader and also impact the US military’s ability to counter foreign aggression in the current era of strategic competition.

Outnumbered and Outpaced

Private companies and many governments make use of the volumes of data amassed from the ever-growing internet-of-things and the many devices individuals have incorporated into their lives to power AI development for noble purposes. But, our competitors and adversaries work tirelessly to outpace the United States: China is stealing large data sets and prioritizing AI development and Russia is conducting relentless and sophisticated cyberattacks against US critical and information systems. The middle powers of Iran and North Korea are also launching attacks on US systems and democratic institutions. Malign activities move across organizational boundaries, pivoting from insecure to well-protected networks, and from networks to hosts, to access key assets and resources. Because national security concerns related to our networks and federal and national security information systems abound, the US military is investing in research and development to create sophisticated AI systems that meet and surpass our adversaries’ capabilities in cyberspace and the information environment to maintain a competitive advantage.

However, with the largest population on the planet, China has access to, and harvests, massive amounts of human data through its social monitoring programs. In 2017, China publicly announced its AI ambitions and its intent to lead the world in AI technology, charting a path to win the race toward computers performing tasks that traditionally require human intelligence to accomplish, like finding patterns in speech, data, or faces. Social monitoring, surveillance, and authoritarian tactics have enabled AI advancements at a social cost impossible to fathom in a free, open, and democratic country—China simply does not have to concern itself with privacy or the social risks inherent to testing, developing, and implementing new technologies. And to augment what its own population already generates, China actively steals data—Chinese actors hacked into the Unique Identification Authority of India database, containing large quantities of biometric information, for example. China has also gathered data from the United States, hacking into the Office of Personnel Management among other US entities. China’s goal appears to be data aggregation—the data available from the Chinese population is large, but by adding foreign data, as well, the potential for AI growth and maturation expands exponentially.

Time to Get Comfortable with Risk

Ultimately, the United States is lagging in AI implementation and, China—in part due to the authoritarian Chinese Communist Party and state-led industry—is much quicker to implement new technologies that may facilitate superior capabilities and lead to an information, military, and economic overmatch. This may include superior weapons, a greater ability to influence the world’s information environment, and economic growth to rival or undermine America’s global leadership and the US dollar’s centrality to the international financial system. In the modern era, information and technology are tightly woven, making it difficult to contain a disruptive technology within national borders. Therefore, despite concerns over the changing nature of work and job security, and a general fear of unknown or unfamiliar technology, the relative advantages of accepting short-term risk and implementing AI-enabled technologies may prove to be the decisive factor in strategic competition and on the future battlefield.

Consequently, AI and the struggle over data, human rights, and ethical use have set the stage for a power struggle between China’s authoritarian state system and the liberal democracy of the West. Until we engage in public dialogue over the ethics and morals of AI development and implementation—on the battlefield and in society as a whole—the United States is destined to fall behind our adversaries by remaining risk averse regarding new technologies. Partly because AI development requires massive data sets to evolve and learn from, and partly because the United States is just beginning to debate the ethics of microtargeting, big data amalgamation, and corporate use of private but publicly available information, the United States has been sluggish and hesitant in its AI implementation. Risk is necessary to AI development, but without an ethical framework through which to assess risk, the United States has little more than business and corporate interests to guide AI implementation. Ultimately, short-term risk aversion is really long-term risk seeking, and the United States should accept risk now to avert a future beholden to Chinese technological overmatch.