Isaac B. Kardon

Building on an NBR study of China’s strategic vision for Africa, this report from NBR’s “Into Africa: China’s Emerging Strategy” project examines the implications of China’s growing presence in Africa’s critical infrastructure. Each essay sheds light on a specific domain of activity—ports, railways, industrial parks, information and telecommunication networks, and power generation—and attempts to understand what it could mean for China’s global ambitions.

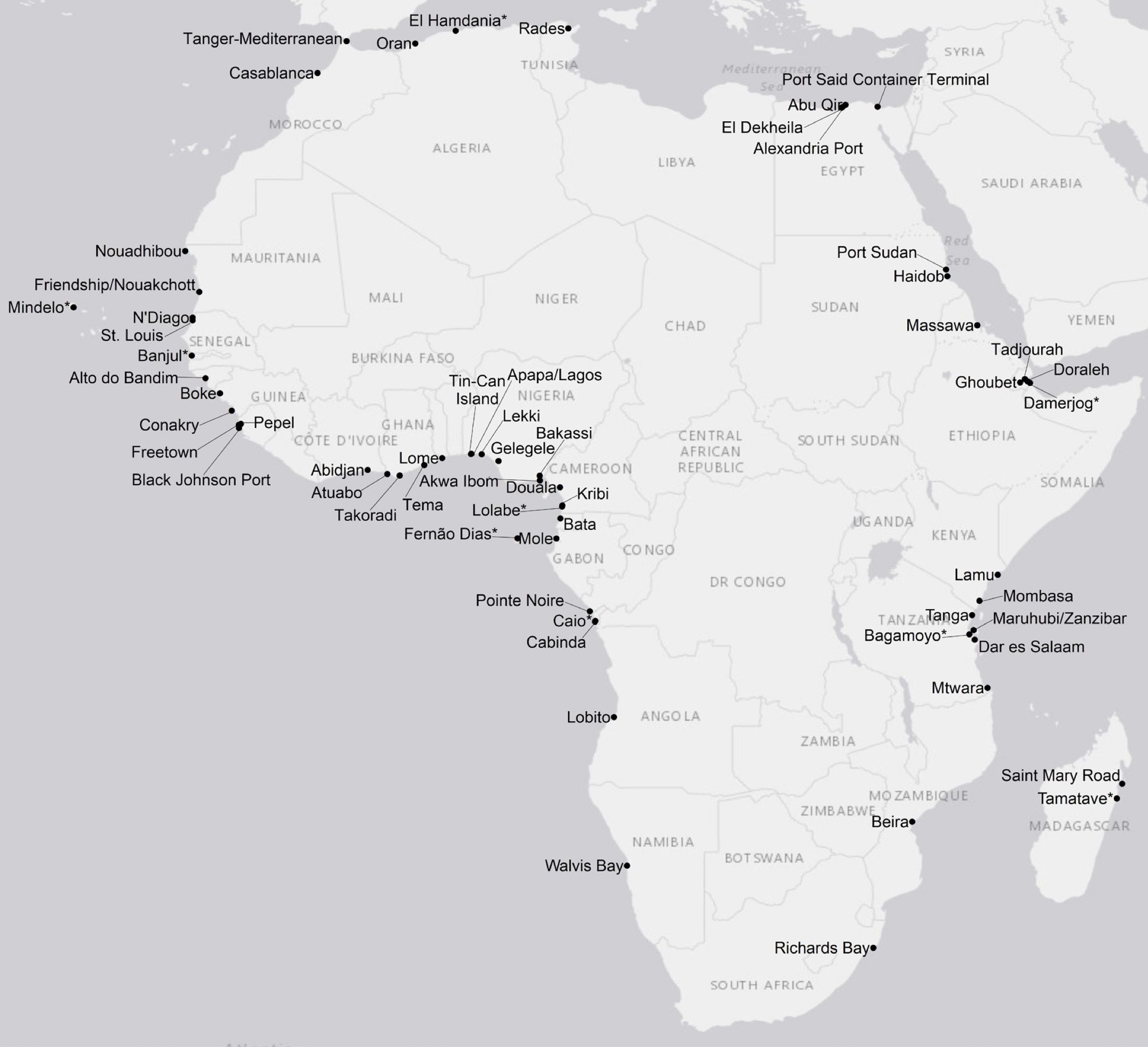

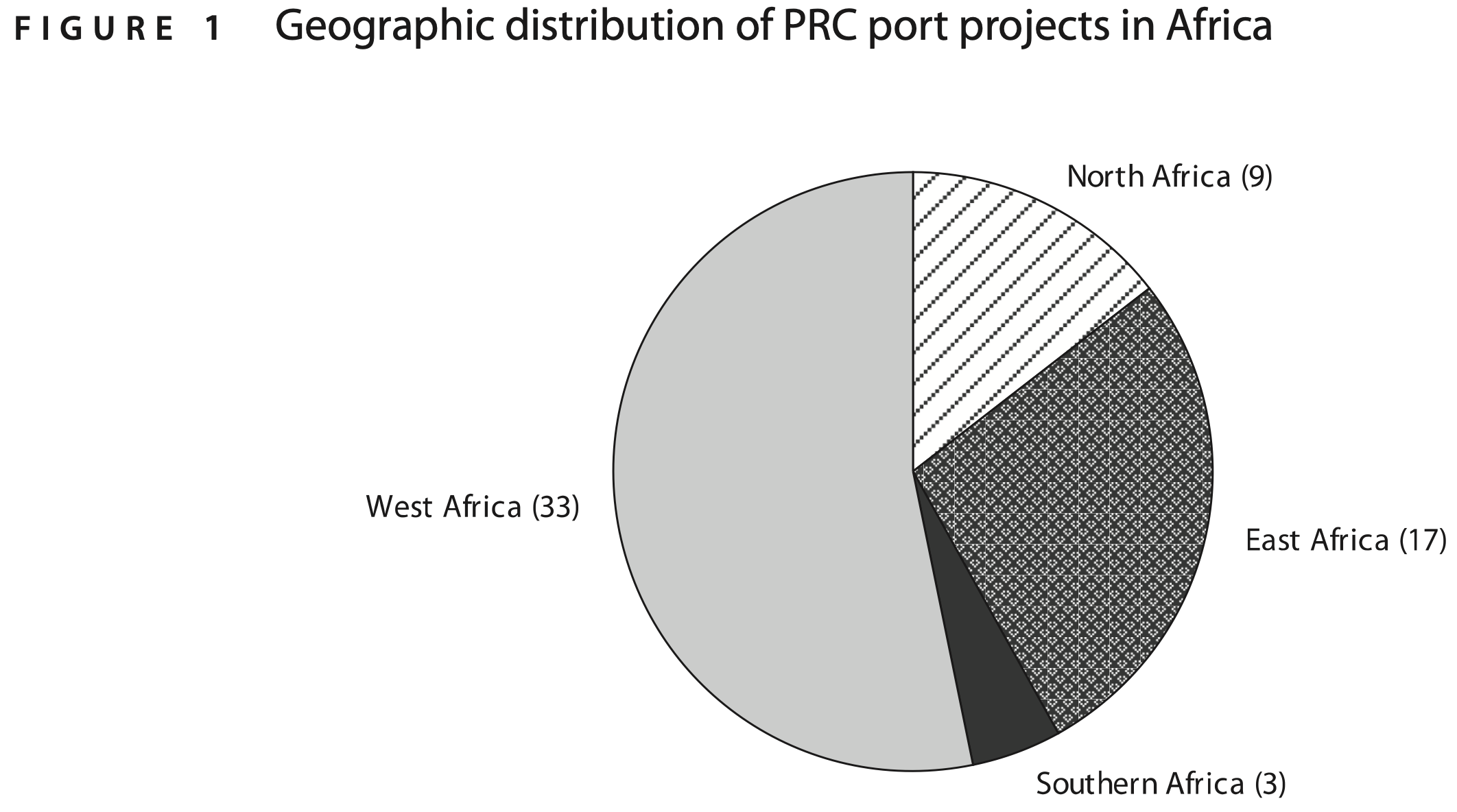

This essay finds that Chinese firms are rapidly developing Africa’s ports as platforms for the integrated political, economic, and military presence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in each of the continent’s subregions.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

MAIN ARGUMENT

Chinese firms are now leading builders, bankers, owners, and operators of ports in Africa. They have quickly achieved significant scale and scope across the continent, using modern, deepwater ports to drive Chinese trade and promote investment in other economic projects past the pier. Several state-owned enterprises have been moving up the value chain in the sector, taking long-term control over ownership and operations of port assets instead of just building them on contracts. Such ports provide robust platforms for China’s economic, political, and diplomatic access in Africa. They also establish ready sites for civil-military dual use. Chinese companies evidently pursue these projects to access African markets and resources, but also to advance broader Chinese foreign policy goals that are competitive with U.S. interests in Africa.

POLICY IMPLICATIONSChinese firms pursue commercial and political incentives within an overall foreign policy framework. So long as PRC foreign policy continues to promote development of African ports as a means to greater access on the continent, Chinese firms will enjoy major cost and scale advantages in further building out Africa’s maritime transport network. The practical policy questions revolve around how to adjust to this reality and mitigate China’s exercise of undue influence through its position in African ports.

The U.S. will not directly compete with China in developing and operating port infrastructure in Africa. But with enhanced U.S. coordination with local allies and partners (including their port and logistics firms) on prioritized countries and projects, Chinese firms can be kept from achieving market dominance. The U.S. can likely remain the great-power partner of choice for key African nations by providing superior security and technology.

Even if Equatorial Guinea does not ultimately agree to host a Chinese military base, some other African state or states will eventually do so. A small number of People’s Liberation Army bases will not tip the Atlantic naval balance nor fundamentally change the basic security dynamics in Africa, but it will alter perceptions of China’s long-term objectives and intensify competition with the U.S.

Analysis

Why has China sought to play such a significant role in the development and operation of African ports? Some insights may be gleaned from official documents and statements, as well as commentary by industry and academic experts in China. These sources help explain PRC firms’ motivations to become Africa’s leading port-builders and prominent financiers, owners, and operators of its port terminals. Chinese companies clearly pursue commercial gain, but are also evidently incentivized to align their port projects with Beijing’s economic, political, and strategic priorities.

The factors pushing and pulling PRC firms into African ports may be stylized in terms of supply and demand. There are certain economic pulls (i.e., demand factors) that both make

maritime transport a priority for Chinese firms and make Africa an especially attractive target for developing and operating trade infrastructure like ports. Meanwhile, PRC firms are also motivated by pushes (i.e., supply factors) from China, which include overcapacity in key sectors and various financial incentives. But, critically, a big push comes from central political inducements to make ports the platform for PRC economic, political, and military access across Africa. … …

In aggregate, there are substantial demand-side drivers for Chinese firms to invest in the continent with the world’s lowest share of maritime trade and largest stores of unexploited natural resources.27 China brings huge scale advantages, insatiable demand for African resources, and an export machine that is always seeking growth into new consumer markets. These are conditions that led CHEC chair and party secretary Lin Yichong to claim that “demand for ports in Africa will inevitably further increase.”28 Chinese firms are uniquely positioned to supply the capital, manpower, and expertise to meet this demand.

The Supply Side of China’s Port Ambitions in Africa

General Secretary Xi Jinping has remarked that “there’s a common saying, ‘if you want to get rich, first build a road,’ but in coastal areas, if you want to get rich, you also need to build a port.”29 Xi, like other Chinese leaders, has long promoted ports connected to roads and rail as the basic platform for economic development.30 Chinese economic planning prioritizes ports as fundamental to the “construction of a strong transport nation,” as emphasized in the authoritative 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–25) and its various supporting official documents.31 As in domestic industrial policy, Chinese leaders also promote ports in their international development plans. This clear priority introduces a set of powerful supply-side forces—that is, motivations originating within PRC officialdom that actively push domestic firms to build and control ports abroad. … …

Implications

PRC firms have pursued ocean ports as key facilitators of China’s economic, diplomatic, and military presence across Africa. A small handful of Chinese SOEs and policy banks have become the central players in Africa’s growing maritime transport sector, positioning Beijing to influence vital flows of trade, investment, data, and capital (financial and political). The 61 (and growing) PRC port projects reflect a simple commercial logic: with virtually all China-Africa

trade conveyed by sea, modern ports serve to expand and consolidate trade flows to and from China. But PRC firms’ enthusiasm for building out trade infrastructure is also a function of national-level objectives and security interests. Achieving greater control over the maritime trade and transport network on which China’s economic system depends—especially for crucial natural resource inputs—is a central policy goal for Beijing that animates the push to develop ports in Africa and elsewhere.

Senior party-state officials prize Chinese firms’ overseas port assets in particular because “port terminals are the highest priority for securing the sea lanes…they are not only for cargo handling, but also provide replenishment and logistics services” required to protect PRC interests overseas— with naval might, if necessary.81 The ports, however, are only one key node in a much more extensive network of maritime infrastructure built, financed, owned, or operated by PRC firms. For example, Huawei Marine has built submarine fiber-optic cables to each of the three ports examined as case studies above, and their other landing points are not coincidentally in other ports in which Chinese firms have established platforms. Chinese shipping lines are ubiquitous in Africa, especially those of the central SOE transport behemoth COSCO Shipping.82 …

More significant near-term implications arise from the vast network of commercial ports that now serve as platforms for Chinese access across Africa. For the military, these facilities help forge new relationships with regional navies, as China emerges as a provider of military technology, training, and assistance. They enable routine intelligence collection and the accumulation of logistical experience by operating task forces around the region. The ports showcase the optics of attractive new PLA Navy surface vessels showing the PRC flag around a distant continent.

They are also the beachhead for wider Chinese engagement in Africa, providing a politically visible and commercially practical point of further access for PRC firms and official actors.

China’s ports in Africa might be essential elements of the inchoate effort “to make Africa a strategic exterior line for China to geopolitically contain the United States,” as observed in the lead report of this wider project on China in Africa.86 The commander of the U.S. Africa Command, General Stephen Townsend, voiced a similar concern when he testified to a House committee that “the thing I think I’m most worried about is this [Chinese] military base on the Atlantic coast.”87 China will need to make much more intensive use of ports in Africa for them to present a meaningful operational challenge to the U.S. military. Yet the opportunity for China to take such a consequential step toward direct strategic competition with the United States in Africa is now latent in the network of ports built, financed, owned, and operated by Chinese firms. The depth and breadth of PRC firms’ positions in African ports make these critical infrastructure assets some of the most likely and useful sites from which China can project power on the continent.