Air Marshal Anil Chopra

The sea-faring Europeans moved out to far-off lands in 17th and 18th centuries after the industrial revolution in search of natural resources. They initially set up facilities at port cities and then moved inland to colonise the nation. After World War II, the Americans and the Soviet Union build military bases across the globe to extend power and influence. Many other powers have set up smaller military bases overseas.

The rising global power China is now doing the same by using its surplus funds, offering financial inducements and using its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to extend influence and acquire military bases abroad. Notable among Chinese military bases is the Ream naval base in Cambodia, People’s Liberation Army Support Base at Djibouti, a military post in south-eastern Gorno-Badakhshan in Tajikistan, and the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force Golden Wheel Project that brings cooperation for positioning and supporting the DF-3 and DF-21 medium-range ballistic missiles in Saudi Arabia since the establishment of Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force in 1984.

A permanent Chinese military installation has come up in Equatorial Guinea on the Atlantic coast. China also has many police and intelligence posts across the globe. They also have research stations, coastal radars, space tracking stations in different parts of the world. Global geopolitics and local opposition continue to pose hurdles. Among its political messaging and global reach, China provides more troops to UN Security Council (UNSC) peacekeeping missions than all the other UNSC permanent members combined. Chinese state-owned enterprises already spend $10 billion on security globally, which includes hiring Chinese security support, ranging from regular military and civilian police to ‘private’ security companies.

Satellite imagery of the Chinese naval base in Djibouti. Image courtesy Google Earth via News.com.au, 2021

Djibouti: The flagship Chinese military base

In 2017, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, on the coast of the Horn of Africa. It is at the strategic entrance to the Red Sea corridor across Yemen. Interestingly, Djibouti also hosts military installations belonging to the United States, the UK, France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. Beijing claims its Djibouti military presence as part of the international effort to combat piracy and protect global trade passing through the Suez Canal. The facilities at the military base support military logistics for Chinese troops in the Gulf of Aden.

The heavily fortified base is 0.5 square kilometres in size and staffed by nearly 2,000 personnel, and has an underground space of 23,000 square meters. There is a 400m runway with an air traffic control tower, as well as a large helicopter apron. There is a PLA Support Base Hospital. Completed in December 2019, the 1,120-foot pier is reportedly long enough to be able to fit the PLAN’s two new aircraft carriers and other warships or at least four nuclear-powered submarines. The close proximity to a US base has created geopolitical tensions.

The United States had earlier blocked a Russian base in 2014, and started a $1 billion upgrade of its base “Camp Lemonnier”. Djiboutian President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh claimed that the United States had a “fixation” about the Chinese base and complained “incessantly” that the Chinese were hampering their operations. He also said that the Japanese were even more worried than the Americans. The Chinese have claimed that the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force sent divers to approach a Chinese warship while it was docked at the base, who were detected and driven off. Both the US and China claim of spy aircraft are being used to snoop on facilities.

Ream Naval Base on 21 May 2021, after the new Chinese construction on the northern end of the base. CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative/Maxar

Ream Naval Base, Cambodia

Ream Naval Base is a facility operated by the Royal Cambodian Navy on the coast of the Gulf of Thailand. The approximately 190 acres base has been the site of annual joint Cambodian-United States training and naval exercises under the Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) programme since 2010.

In July 2019, Western media revealed that a secret agreement allowed the Chinese PLA Navy (PLAN) exclusive access to about one-third of the Ream naval base for up to 30 years. It would give Beijing a new southern flank on the South China Sea (SCS), and only its second overseas naval foothold after a base in Djibouti. Such hosting of foreign armed forces was against the Cambodian constitution as well as the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements that ended the Cambodian Civil War.

Cambodia initially denied such lease, but in 2021, the Cambodian defence minister admitted that China was helping build infrastructure at Ream and continued to maintain that there were no strings attached. One of two US-funded buildings on the base was demolished in September 2020. In October 2020, dredging work was undertaken around the base, in order to accommodate larger vessels, in a project supported by the Chinese Government. The USA slapped arms and a dual-use-item embargo on Cambodia on in December 2021, even though this may push Cambodia closer to China. There has been an adverse reaction from Cambodian opposition and the public to China militarising Cambodia’s coast in the garb of ambitious infrastructure projects.

China has reconstructed and extended a deep water commercial port in Bata, Equatorial Guinea. Image courtesy SCMP Weibo handle

China’s military base in Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea is one of Africa’s smallest countries overlooking the Atlantic and brings China physically closer to the USA and Europe. Beijing plans to set up a permanent military naval installation. It also exposes it African investment policy and intent and sends shivers on other aid-receiving African nations.

The West sees it as having far-reaching geopolitical implications. Africa is the largest recipient of China’s $1 trillion BRI with 46 African nations (over 1 billion people) being on board. The new military bases also mean eroding US dominance.

There are already nearly 10,000 Chinese enterprises in Africa, generating $180 billion a year in revenues and could reach $250 billion by as early as 2025, according to a 2017 McKinsey report. Nearly one million Chinese citizens live in Africa to support and operate Chinese investments. China has its own integrated economic, policing, and security apparatus to secure these assets, albeit there are no overt heavy troop presence in the continent yet.

The Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) coordinates between China and all states in Africa (except the Kingdom of Eswatini, which recognises Taiwan). Beijing is already looking at creating a pan-African security architecture with China at its core. The deep-water commercial port, and naval base, in Equatorial Guinea may be the beginning of that phase. The port could be used for rearming with munitions and repair naval vessels. Equatorial Guinea boasts the highest GDP per capita, primarily because of its over 1 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves.

While US oil companies have conducted most of Equatorial Guinea’s oil exploration and production, China has become the country’s primary development partner. The Chinese banks funded the $2 billion oil-backed buyer’s credit facility at the Port of Bata that was eventually inaugurated in 2019. For years led by very corrupt, self-serving leaders, Equatorial Guinea has now become increasingly indebted to China with debt in 2021 mounting to 49.7 per cent of GDP. Despite last-minute US intervention and advice, the current government appears to be moving ahead with plans to host a Chinese naval base.

Chinese work halted at Khalifa port in UAE. Image courtesy adports.ae

Cargo Port at Khalifa, UAE

In 2018, the UAE and China signed a $300 million deal to upgrade the COSCO Shipping Ports Abu Dhabi Terminal. This port is located near both Al Dhafra Air Base and Jebel Ali port. The latter in Dubai is the busiest port outside the USA for US Navy ship visits. China’s giant COSCO shipping conglomerate had built and now operates a commercial container terminal at Khalifa. There were allegations that secret military facilities were being developed there clandestinely. The UAE was not in the picture.

The UAE has never had an agreement, plan, talks or intention to host a Chinese military base or outpost of any kind, UAE. Embassy in Washington confirmed. Alarmed US officials warned Emirati government, a Mideast ally, that Chinese military presence could hinder ties. The construction was halted.

China’s effort to establish a military foothold in the UAE reflects the challenges the West and the world at large face from Chinese influence peddling. The UAE is a major oil and gas producer and hosts US military forces. It was the first Arab country to send troops to Afghanistan following the US intervention in late 2001.

The US had recently brokered the Abraham Accords that normalized relations between Israel and some Gulf States, including the UAE. Beijing was building counters with trade deals and now trying to expand its military presence. In recent years, China has strengthened its economic ties with the UAE and is now one of its largest trading partners as well as the biggest consumer of Gulf oil.

The UAE, meanwhile, has embraced China’s Huawei Technologies Co.’s telecom infrastructure, which senior Western officials warn leaves it vulnerable to Chinese espionage. The UAE cooperation with China had threatened the planned $23 billion sale of as many as 50 US F-35 fifth-generation fighter aircraft, 18 Reaper drones and other advanced munitions. But the deal is back on track.

Construction of a new Chinese-funded base in Tajikistan. Satellite image courtesy Radio Free Europe

Gorno-Badakhshan Tajikistan

The US intelligence agencies have reported that China will build a new base for special operations near the Afghanistan border. It will be located in the eastern Gorno-Badakhshan autonomous province near the Pamir Mountains. Tajikistan’s Interior Ministry and China’s Public Security Ministry (Police) signed an agreement. The focus would be on counterterrorism amid rising concerns over instability in neighbouring Afghanistan.

The base will be owned by Tajikistan’s Rapid Reaction Group or Special Forces and financed by China for a cost of $10 million. Currently, Chinese troops will not be stationed there. Earlier there were reports of a secret Chinese military base located in the Murghab district a few kilometres from the new base. China is thus trying to get a military base in Tajikistan.

Gwadar Port. Image courtesy Modern Diplomacy

Port at Gwadar

China has built commercial port facilities in Pakistan and Sri Lanka that could be used by its rapidly expanding navy. The Gwadar Port in the Balochistan province of Pakistan is situated on the Arabian Sea. It is under the administrative control of Pakistan and operational control of the China Overseas Port Holding Company. The port is an important part of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). It is 170 kilometres to the east of Chabahar Port in Iran.

Gwadar’s potential to be a deep-water sea port was first noted in 1954, while the city was still under Omani sovereignty. The port was inaugurated 2007 by Pervez Musharraf after four years of construction, at a cost of $248 million. In 2015, it was decided that the city and port would be further developed under CPEC at a cost of $1.62 billion. The port will also be the site of a floating liquefied natural gas facility that will be built as part of the larger $2.5 billion Gwadar-Nawabshah segment of the Iran–Pakistan gas pipeline project. Construction began in June 2016 on the Gwadar Special Economic Zone, which is being built on 2,292-acre site adjacent to Gwadar’s port.

In 2017, around 2000 acre land was leased to a Chinese company for 43 years for the development of Gwadar Special Economy Zone. On 31 May 2021 Gwadar Port became fully operational.

The Straits of Malacca provide China with its shortest maritime access to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Malacca is dominated by many adversary navies. Gwadar Port is now a means to circumvent the Straits of Malacca. The sea route via the Straits of Malacca is roughly 12,000 kilometres, while the distance from Gwadar Port to Xinjiang province is approximately 3,500 kilometres. However, the cost of moving oil overland is far greater. Even if an oil pipeline were to be built, its initial cost will be very high. Yet, the CPEC project and the Sino-Myanmar pipelines will help Chinese energy imports to circumvent the “Malacca Dilemma”.

More importantly, China’s stake in Gwadar would give it another naval logistic and basing facility. It will also complement China’s Western Development plan, which includes not only Xinjiang, but also the neighbouring regions of Tibet and Qinghai. China will allow CPEC and Gwadar to various Central Asian republics and gain dependency and influence.

The PLAN exercises regularly with the Pakistan Navy (PN). PLAN anti-piracy escort force regularly calls at Karachi on their way to deployments in the Gulf of Aden. PN inventory has a large number of Chinese-origin ships and platforms. Reports have surfaced of the deployment of Chinese submarines at Gwadar. One day Gwadar could hold large ships of the size of aircraft carriers. Gwadar will also allow PLAN enhanced military monitoring capability in the region.

Chabahar port. Image courtesy Modern Diplomacy

Comparison to Chabahar Port projects

India Ports Global Private Limited is refurbishing a 640-meter-long container handling facility and reconstructing a 600-meter-long berth at the Port of Chabahar, Iran, and modernising ancillary infrastructure at the berths. This will allow Indian goods to be exported to Iran, with the possibility of onward connections to Afghanistan and Central Asia, and even Russia and Europe. Chabahar is at a much smaller scale and investment and cannot be considered as a counter to Gwadar. Interestingly, both Pakistan and China had been invited to contribute to the Chabahar project before India, but neither China nor Pakistan had expressed interest in joining.

Hambantota International Port, Sri Lanka. Image courtesy Maritime Gateway

Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka

The deep water Hambantota International Port, Sri Lanka was opened on 18 November 2010, and is Sri Lanka’s second largest port, after the Port of Colombo. In 2020, the port handled 1.8 million tonnes of LPG and dry bulk cargo. In 2016, at operating profit of just US$1.81 million it was considered economically unviable.

As debt repayment got difficult, the government decided to privatise. 70 per cent stake was sold to raise foreign exchange in order to repay maturing sovereign bonds unrelated to the port. China Merchants Port won the bid and paid US$1.12 billion to Sri Lanka, and were to spend additional amounts to develop the port into full operation. Simultaneously a 99-year lease on the port was granted to the company.

Sri Lanka is situated along the key shipping route between the Malacca Straits and the Suez Canal, which links Asia and Europe. An estimated 36,000 ships, including 4,500 oil tankers, use the route annually. The Port at Colombo, caters mainly to container handling and was unable to provide facilities for port-related industries and services. Hambantota, which has a natural harbour is located on the southern tip of Sri Lanka and closer to international shipping routes. It would also save time for the detour to Colombo. In July 2018, the Sri Lankan government announced it would relocate its naval base at Galle to Hambantota.

Hambantota was important for China’s economic and military expansion in the Indian Ocean, enhancing its footprint of ‘strategic support bases’ through the backdoor (debt-trap diplomacy). India and the United States had raised concerns that Chinese control of the Hambantota port could harm their interests in the Indian Ocean.

In February 2021, the Sri Lankan foreign minister Dinesh Gunawardena said the lease of the Hambantota port to China was a mistake made by the previous government, and that Colombo was revisiting the agreement. There is no way Beijing will dilute the lease given the fact that China doesn’t seal a deal of this nature with assured strategic gains without buying the host country’s hierarchy.

Interestingly, in May 2019, Sri Lanka signed a deal with India and Japan to develop the deep-sea East Container Terminal at the Colombo Port. Sri Lanka retains 51 per cent stakes with India and Japan 49 per cent each.

In a related development, Feydhoo Finolhu, the nearest uninhabited island to capital Malé in the Maldives, was leased to China for 50 years in 2017, and is being expanded by reclamation and increasing Chinese BRI footprint in the Indian Ocean.

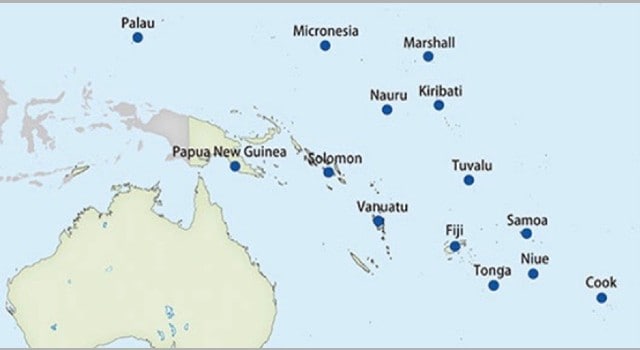

Chinese interest in the “Little Children” of South Pacific. Image courtesy Asia Media International

China in Pacific Islands

China has already emerged as the Pacific Islands region’s largest lender by disbursing bilateral loans amounting to US $1.3 billion between 2012 and 2022. Chinese loans account for more than 60 percent of Tonga’s external debt, and 50 percent of Vanuatu’s. Chinese government has signed a security deal with the Solomon Islands which paves the way for China to deploy security forces and PLAN could use the ports of the Pacific island nation. This gives China a strategic foothold in the Pacific. The agreement evoked concern from Australia and the United States. In 2018 Vanuatu became a signatory to BRI. More recently, Chinese involvement in the Solomon Islands has been highlighted, with the late-November riots resulting in large parts of Honiara’s Chinatown being burned down. In 2019, the Solomon authorities proposed to lease Tulagi Island to a Chinese developer for a special economic zone. The agreement was finally never concluded. China has also been exerting influence in Kiribati. China hosted a Pacific islands meeting in Fiji, in May 2022, with security ties in focus. A draft communique and five-year action plan was sent by China to the invited nations, which included Samoa, Tonga, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, and Niue ahead of the meeting. China was seeking a sweeping regional trade and security agreement. The United States, Australia, Japan and New Zealand expressed concern and the proposal could not be pushed through.

Chinese Police Overseas Service Stations

The “overseas service station” also called “Overseas 110” (the emergency number for police) were established by China’s Ministry of Public Security in other countries starting 2014. As of October 2022, a total of 54 such stations had been established in 30 countries These centers did not have policing authority but were meant to assist crime victims while dealing with the host country’s police and integrating new immigrants. China claims that they provide Chinese nationals in foreign countries with bureaucratic assistance, such as document renewals, and to fight transnational crime. However, in 2022, a human rights group published a report that these offices were part of a programme named “Operation Fox Hunt”, and were used to harass and coerce individuals wanted by the Chinese government, including dissidents. Modus operandi was threats to their families and themselves, pressuring them to return to China where they would then be detained.

The report led to increased scrutiny and investigations of the stations by the governments of host countries. They were accused of political influence operations. In response, some countries, such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands began investigating and some, such as, the overseas service stations in Dublin were ordered to close in October 2022.

The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs also stated that, as the Chinese government had failed to notify the country about the stations through diplomatic means, they had been operating illegally, with further investigation to be conducted into their conduct. In November 2022, Canada summoned the Chinese ambassador and issued a “cease and desist” warning concerning the stations. In December 2022, Italy announced that its police would cease joint patrols with Chinese police officers inside of Italian cities. There were no such stations in India.

Conclusion

The traditionally inward looking China has become more extrovert in its military aspirations since Chairman Xi Jinping took over the reins. The US Department of Defence is on record as saying that China is pursuing additional military facilities to support naval, air, ground, and cyber and space power projection. The USA has made a list of potential locations for new Chinese bases which include Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, UAE, Kenya, Seychelles, Tanzania, Namibia, Angola and Tajikistan.

In March 2017, China announced increasing its marine corps from 20,000 to 100,000 for overseas tasks (mentioning Djibouti and Gwadar), plus increasing PLAN’s strength by 15 percent from the existing 2,35,000. Chinese overseas projects usually have covert PLA presence, as would be in Hambantota and Colombo. Sri Lanka clearly is the diamond in China’s ‘string of pearls’ surrounding India and Beijing is intent on dominating the India Ocean. There is speculation that China’s Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs) will be operational in the Indian Ocean within five years. Djibouti and Pakistan would be MEU bases for sure but mobile MEUs patrolling the seas could berth at Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar on the pretext of rest, recoup and repairs. Enlarged PLAN presence around Sri Lanka can hinder the switching of Indian naval forces between the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.

But everything is not smooth sailing. Gwadar which has been the poster child of potential Chinese military bases, is facing security threats related to terrorism and separatist activities. China’s predatory lending practices have resulted in debt-trap issues in most BRI recipient countries. Many countries in Asia and Africa are initial victims of Chinese geostrategic leveraging through debt. Free world has realised the Chinese expansionist designs, and are intervening with host nations. The non-repayment of debt by many countries is already putting pressure on Chinese banks and economy. Clearly China is facing hurdles in getting more military bases abroad.

No comments:

Post a Comment