Clint Watts

As we report more fully below, in the wake of Russian battlefield losses to Ukraine this fall, Moscow has intensified its multi-pronged hybrid technology approach to pressure the sources of Kyiv’s military and political support, domestic and foreign. This approach has included destructive missile and cyber strikes on civilian infrastructure in Ukraine, cyberattacks on Ukrainian and now foreign-based supply chains, and cyber-enabled influence operations[1]—intended to undermine US, EU, and NATO political support for Ukraine, and to shake the confidence and determination of Ukrainian citizens.

In recent months, cyberthreat actors affiliated with Russian military intelligence have launched destructive wiper attacks against energy, water and other critical infrastructure organizations’ networks in Ukraine as missile strikes knocked out power and water supplies to civilians across the country. Russian military operators also expanded destructive cyberactivity outside Ukraine to Poland, a critical logistics hub, in a possible attempt to disrupt the movement of weapons and supplies to the front.

Meanwhile, Russian propaganda seeks to amplify the intensity of popular dissent over energy and inflation across Europe by boosting select narratives online through state-affiliated media outlets and social media accounts to undermine elected officials and democratic institutions. To date, these have had only limited public impact, but they foreshadow what may become broadening tactics during the winter ahead.

We believe these recent trends suggest that the world should be prepared for several lines of potential Russian attack in the digital domain over the course of this winter. First, we can expect a continuation of Russia’s cyber offensive against Ukrainian critical infrastructure. We should also be prepared for the possibility that Russian military intelligence actors’ recent execution of a ransomware-style attack – known as Prestige – in Poland may be a harbinger of Russia further extending cyberattacks beyond the borders of Ukraine. Such cyber operations may target those countries and companies that are providing Ukraine with vital supply chains of aid and weaponry this winter.

Second, we should also be prepared for cyber-enabled influence operations that target Europe to be conducted in parallel with cyberthreat activity. Russia will seek to exploit cracks in popular support for Ukraine to undermine coalitions essential to Ukraine’s resilience, hoping to impair the humanitarian and military aid flowing to the region. The good news is that, when equipped with more information, a media-savvy public can act with awareness and judgment to counter this threat.

Here’s what we are seeing at Microsoft since Ukraine’s counteroffensive has pushed the Russian army into retreat, what we anticipate Russia’s cyber and influence operations might look like headed into the winter months, and how we at Microsoft will help prepare and prevent harm to Microsoft customers and democracies facing these attacks.

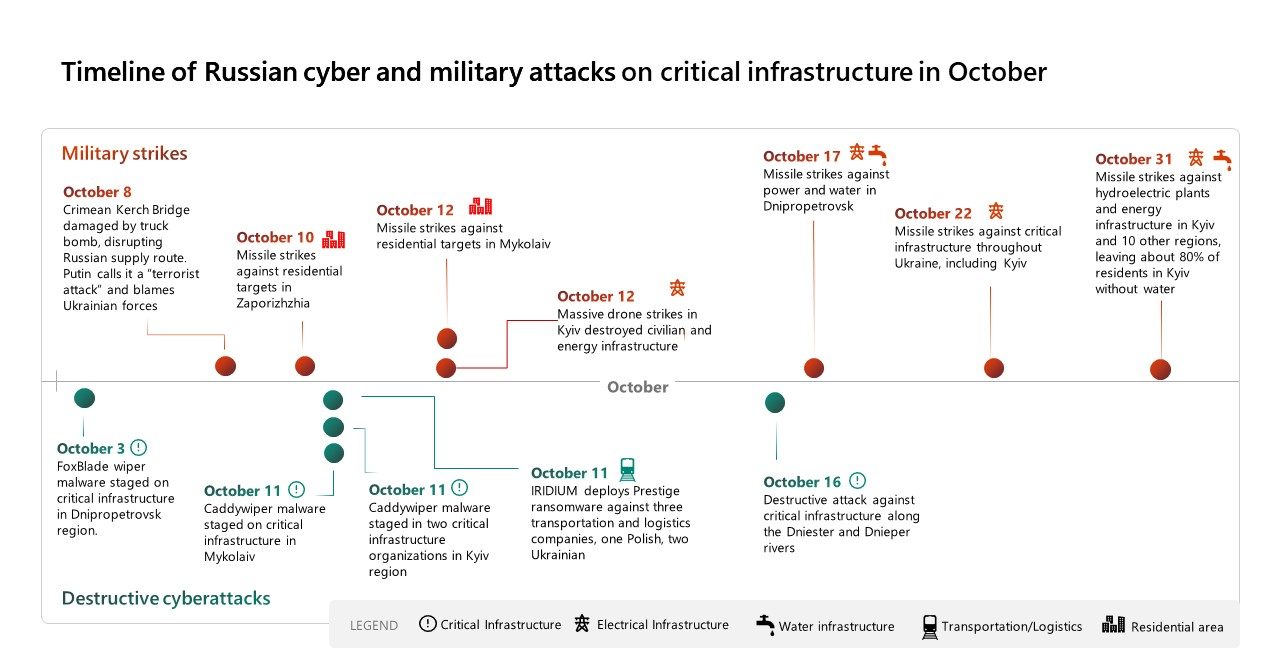

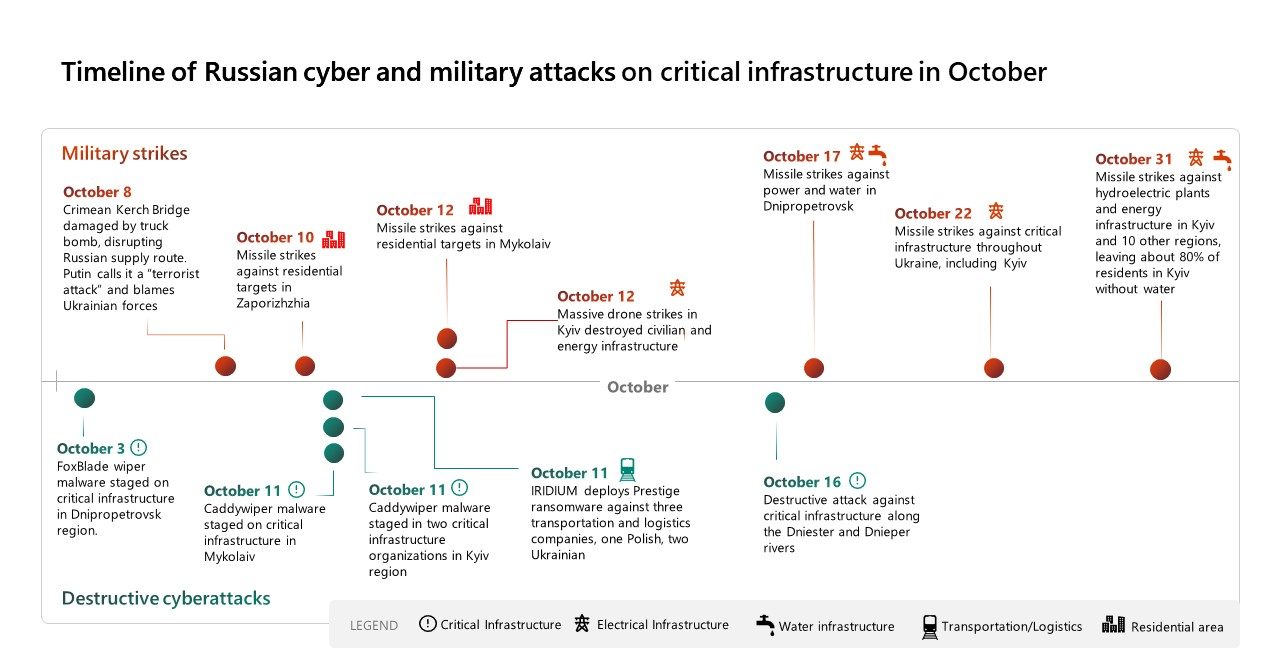

Combined missile and cyber strikes focus on destruction of civilian infrastructure

As Russia retreated from formerly occupied territory in Ukraine in late October, the Kremlin unleashed new missile and drone strikes against Ukrainian cities and the energy and transportation infrastructure that supports them. Missile barrages cut power to more than 10 million Ukrainians and left up to 80% of Kyiv’s population without running water.[2] The intent to inflict suffering on Ukraine’s civilians has been clear, and was effectively acknowledged by Russian officials.[3]

Notably, these recent missile strikes have been accompanied by cyberattacks on the same sectors, perpetrated by a threat group – known at Microsoft by the element name IRIDIUM and by others as Sandworm – associated with Russia’s military intelligence service, the GRU. The repeated temporal, sectoral and geographic association of these cyberattacks by Russian military intelligence with corresponding military kinetic attacks indicate a shared set of operational priorities and provides strong circumstantial evidence that the efforts are coordinated, as reflected in the timelines below.

Microsoft’s research of IRIDIUM shows a history of destructive attacks against Ukraine’s critical energy infrastructure that dates back nearly a decade. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, IRIDIUM launched a series of wintertime operations against Ukrainian electricity providers, cutting power to hundreds of thousands of citizens in 2015 and 2016.[4] The group’s pursuit of destruction in Ukraine spread globally in 2017 with the NotPetya attack, which inflicted $10 billion of damage to companies including international firms such as Maersk, Merck and Mondelēz, and underscores the risk of this actor’s operations to the global digital ecosystem.[5]

The wave of Russian destructive cyberattacks that began on February 23, and subsequent destructive attacks against Ukrainian targets in support of the Russian war effort have been the responsibility of IRIDIUM, as we have previously reported.[6] In October, IRIDIUM’s destructive attacks against Ukrainian critical services networks spiked, after two months of little to no wiper activity. As the Ukrainian counteroffensive progressed and winter approached, Microsoft observed that IRIDIUM deployed Caddywiper and FoxBlade wiper malware to destroy data from networks of organizations involved in power generation, water supply and the transportation of people and goods. The predominant focus was on the Kyiv region, as well as the southern and central-eastern regions of the country, where the physical conflict has been the most intense.

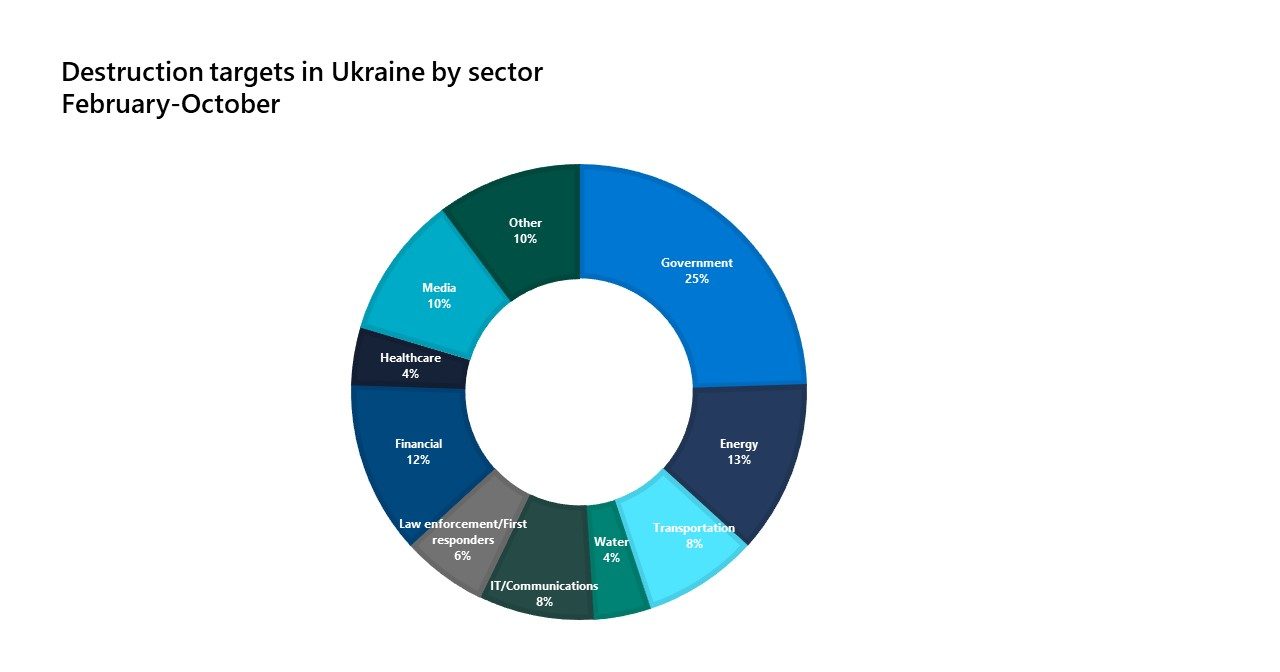

Cyber and missile strikes on transportation and logistics companies may interfere with the transportation of weapons and supplies. However, such attacks can also disrupt the passage of humanitarian aid to Ukrainian citizens, compounding the harm from curtailing the supply of electricity. This tactic of targeting civilian infrastructure has been in play since the beginning of the conflict. Of the roughly 50 Ukrainian organizations that Russian military operators have hit with destructive wiper malware since February 2022, 55% were critical infrastructure organizations, including in the energy, transportation, water, law enforcement and emergency services, and health care sectors.

This tactic of targeting civilian infrastructure has been in play since the beginning of the conflict. Of the roughly 50 Ukrainian organizations that Russian military operators have hit with destructive wiper malware since February 2022, 55% were critical infrastructure organizations, including in the energy, transportation, water, law enforcement and emergency services, and health care sectors.

This tactic of targeting civilian infrastructure has been in play since the beginning of the conflict. Of the roughly 50 Ukrainian organizations that Russian military operators have hit with destructive wiper malware since February 2022, 55% were critical infrastructure organizations, including in the energy, transportation, water, law enforcement and emergency services, and health care sectors.

This tactic of targeting civilian infrastructure has been in play since the beginning of the conflict. Of the roughly 50 Ukrainian organizations that Russian military operators have hit with destructive wiper malware since February 2022, 55% were critical infrastructure organizations, including in the energy, transportation, water, law enforcement and emergency services, and health care sectors. In most instances, threat actors have deployed wipers against the business networks of the targeted critical infrastructure organizations. However, operational technology networks are also vulnerable. For example, IRIDIUM attempted to inflict severe damage on energy production in April by targeting the industrial control systems (ICS) of a Ukrainian energy provider.[7] Quick action by CERT-UA and international partners thwarted the attack, but the risk of future ICS attacks that would disrupt or destroy the productive capacity of Ukrainian power or water infrastructure is high.

In most instances, threat actors have deployed wipers against the business networks of the targeted critical infrastructure organizations. However, operational technology networks are also vulnerable. For example, IRIDIUM attempted to inflict severe damage on energy production in April by targeting the industrial control systems (ICS) of a Ukrainian energy provider.[7] Quick action by CERT-UA and international partners thwarted the attack, but the risk of future ICS attacks that would disrupt or destroy the productive capacity of Ukrainian power or water infrastructure is high.Russian cyberattacks extend outside Ukraine

Russian cyber strikes extended outside Ukraine in October, when IRIDIUM deployed its novel Prestige ransomware against several logistics and transportation sector networks in Poland and Ukraine.[8] This was the first war-related cyberattack against entities outside of Ukraine since the Viasat KA-SAT attack at the start of the invasion.[9]

The Prestige event in October may represent a measured shift in Russia’s cyberattack strategy, reflecting a willingness by Moscow to use its cyberweapons against organizations outside Ukraine in support of its ongoing war. Since Spring 2022, Microsoft has observed that IRIDIUM and suspected Russian state operators have targeted transportation and logistics organizations across Ukraine in probable attempts to collect intelligence on or disrupt the flow of military and humanitarian aid through the country. But these recent attacks in Poland suggest that Russian state-sponsored cyberattacks may increasingly be used outside Ukraine in an effort to undermine foreign-based supply chains.

IRIDIUM’s success in the Prestige destructive attack was limited. Early customer notifications and rapid response, including from Microsoft’s Detection and Response Team (DART) and the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC), along with local incident responders in Poland, reportedly helped contain the attack’s impact to less than 20% of one targeted organization’s network. However, while the destructive impact was limited, IRIDIUM almost certainly collected intelligence on supply routes and logistics operations that could facilitate future attacks.

Perhaps in part because the impact was successfully limited by the defenders and responders in this instance, international outcry against this new extension of the hybrid war beyond the borders of Ukraine has been muted. Nevertheless, this attack highlights the continued risk of Russian destructive cyberattacks to European organizations that directly supply or transport humanitarian and military assistance to Ukraine.

Cyber-enabled influence operations seek to fuel real-world discord across Europe

This winter, European populations seeking to keep warm amid energy shortages and heightened inflation will likely be targeted by Russian attempts to stir up and potentially mobilize grievances through cyber-enabled influence operations.

Such operations offer the Kremlin a more deniable but nonetheless effective method of shaping discourse around conflict and major geopolitical events. Russia’s “active measures” approach involves infiltrating the constituencies of Kremlin adversaries while elevating candidates and officials who share Russia’s preferred foreign policy positions. Since 2014, Russia has sought to achieve its objectives “through the force of politics, rather than the politics of force,”[10] across democratic contests including the 2016 Brexit referendum and elections in the US, France and Germany, among others. Russia has also exploited political, economic and social divisions to mobilize citizens and even incite violence inside democracies. It is likely that these tools will be deployed in Europe and globally to reduce support for Ukraine’s defense.

Russia has a well-established ability to sway public opinion both in the U.S. and Europe through cyber-enabled influence operations. In 2016, the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg, known better as the Russian “troll farm,” famously orchestrated protests in Texas[11] and Florida.[12] Earlier that same year, Russian state media ran a story about an alleged assault of a young girl by migrants in Germany – accusations later disproved – and promoted the narrative that the German government had deliberately concealed the truth. The subsequent media flurry sparked a series of protests within Germany’s sizeable Russian diaspora, who were outraged by what they were being told was failure on the part of the German justice system.[13]

In 2018, the same Kremlin trolls involved in the 2016 US presidential election amplified the “yellow vest” protests in France. Russia did not organize these protests, but its online campaigns elevated calls to protest President Emmanuel Macron’s government by using a blend of overt, state-sponsored media to promote the cause while boosting the movement’s hashtag #giletsjaunes via covert accounts online.[14]

Our Digital Threat Analysis Center (DTAC) team closely tracks cyber-enabled influence operations. Protests in Europe this fall related to energy, inflation, and the war in Ukraine broadly – and their steady promotion by Russian propaganda outlets – foreshadow additional operations we may encounter this winter in support of Russian objectives by seeking to increase European dissatisfaction with energy supply, energy pricing and inflation.[15] If energy and electricity disruptions in Ukraine lead to more refugees throughout Europe, Russian cyber-enabled influence operations may seek to increase frictions over migration to create intra- and inter-country conflicts – a theme visible in the Kremlin’s campaigns over the last decade as refugees fled to Eastern and Central Europe during the Syrian Civil War.[16]

In the coming months, European nations will likely be subjected to a range of influence techniques tailored to their populations’ concerns about energy prices and inflation more broadly. Russia has and will likely continue to focus these campaigns on Germany, a country critical for maintaining Europe’s unity and home to a large Russian diaspora, seeking to nudge popular and elite consensus toward a path favorable to the Kremlin.[17] Strong connections between Kremlin-affiliated ideologues and Germany’s far right will likely be leveraged both online and offline in campaigns targeting German audiences with hardline narratives on the war in Ukraine as well as criticism of the government’s handling of the energy crisis.[18]

Recent quantitative analyses support these assessments. Microsoft’s AI for Good Lab has created a Russian Propaganda Index (RPI) to monitor the consumption of news from Russian state-controlled and state-sponsored news outlets and amplifiers. This index measures the proportion of this propaganda flow to overall news traffic on the internet. The RPI in Germany currently is the highest in Western Europe, over three times the regional average.

Higher Russian propaganda consumption in Germany may be in part due to decades of Russian investment in soft power and public diplomacy targeting the country, home to one of the largest Russian diaspora populations in Europe. Many of the soft power organizations’ express purpose is to create people-to-people and party-to-party ties between the two countries, and several Russian state-sponsored media outlets have been based in Germany.[19] Germany’s large Russian-speaking population, estimated at nearly 6 million people, makes Russian cyber-enabled influence operations and propaganda published in both Russian and German more accessible to German audiences.[20] Meanwhile, German policy since the end of the Cold War, during which time Soviet and East German active measures efforts were conducted synergistically,[21] has sought a normalization of relations with Russia bolstered by economic cooperation, with no greater example than the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline. U.S. sanctions against this project, unpopular in both Russia and Germany, gave anti-Western and pro-Russian propaganda and influence operations, particularly on economic and energy topics, a more sympathetic audience.[22]

Throughout Western Europe, readers are exposed to Russian propaganda on both Russian-language sites – including Russian state-owned media sites – and local-language, pro-Russia sites. Consumption of local-language sites in Germany is three times higher than the Western European average, in keeping with Germany’s high levels of Russian propaganda consumption in the aggregate. In Germany, the local-language sites that generate the most traffic are anti-spiegel.ru, uncutnews.ch and the German-language edition of Russia Today (RT), de.rt.com. Local sites focus more attention on local issues. Anti-Spiegel in particular has focused its content on leveraging the current economic climate to promote the Kremlin and vilify the West. The headlines of its three most-read articles, for example, from the last four months are:“That the US wants to destroy the German economy is considered a conspiracy theory and Russian propaganda, but it is obvious.”[23]

“The Nord Stream pipelines have been blown up and the Western media are staging what is arguably the stupidest propaganda operation ever.”[24]

“I am often asked why I am so convinced that Russian President Putin is not part of [the World Economic Forum] & Co. and its new world order. Here I want to answer that.”[25]

Aside from Germany, many other European nations may also need to reckon with the combined weight of Russian meddling and organic popular discontent. Earlier this year, Russia-affiliated threat actor SEABORGIUM (which overlaps with threat groups tracked as Callisto Group, TA446 and COLDRIVER) targeted the UK, utilizing allegedly stolen material to sow distrust in the British government,[26] while pro-Russia media like Modern Diplomacy and Strategic Culture Foundation, an outlet directed by the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR),[27] publish content alleging British involvement in the Kerch Strait Bridge explosion.[28]

Ongoing protests in the Czech Republic, meanwhile, have promoted Russia’s talking points on energy and are repeatedly featured in Russian state-owned and state-affiliated media.[29] Ladislav Vrábel – one of the organizers of the protest movement Czech Republic First – has been a repeated guest on Russian media such as Sputnik News since protests began,[30] while PolitNavigator – a Russian-language site reportedly directed by the FSB[31] – sent a correspondent to cover the protests from the beginning.[32] Further, among public figures who supported and spoke at the demonstrations are several politicians with long and well-documented records of pro-Russian activity, such as unofficial trips to occupied Crimea and high-level involvement with Kremlin-funded biker gang Night Wolves.[33]

France, not as reliant on Russian gas as its neighbors, is perhaps less vulnerable to energy-related influence. However, there is an ongoing risk that Russian agencies will seek to meddle in French affairs through inauthentic social media campaigns – building on previous efforts[34] and its success seeding and exploiting anti-French sentiment throughout Africa via propaganda, fake think tanks, and local engagement – which point to Russia’s willingness undermine French leadership.[35] Finally, Italy, with rising energy costs,[36] emerges as an additional target.

Defending the digital domain this winter: A way forward

In our June 2022 report, Defending Ukraine: Early Lessons from the Cyber War, Microsoft offered a methodology for combating digital threats. Multidimensional threats require multidimensional defenses. At Microsoft, we’ve built our approach around “Four Ds” to counter malicious cyber and influence activity. Throughout the winter and into 2023, we will be working with our customers and in support of democracies to:Detect: Collectively identify, across Microsoft’s threat intelligence teams, those cyber actors that may strike at supply chains supporting Ukraine and the energy industry keeping Europe warm this winter. We will also evaluate cyberattacks to determine which are designed to limit support and supplies to Ukraine and which may be part of broader hack-and-leak operations designed to undermine unity of support for Ukraine. For customers, we’ll preemptively evaluate and assess potential risks to those that may be targets of Russia or other nation state threat actors. This vulnerability assessment will closely evaluate transportation, defense and energy companies Microsoft serves to help increase the collective speed of detection and response. Microsoft will also continue to track and identify Russian cyber-enabled influence operations, publishing our findings to notify the public and industry partners to improve information integrity of our own platforms and broader detection efforts.

Disrupt: Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) will alert customers and the public to emerging cyber methods enabling the entire ecosystem to rapidly employ sensors, patches, and mitigations. Where we encounter cyber-enabled influence campaigns, we will pursue a similar strategy, shining a light on operations aimed at creating doubt, distrust or dissent within Ukraine or across its partners seeking to undermine support for Ukraine. Our team will share this information with our customers and the public to these operations and lessen their impact.

Defend: Microsoft will increase the collective defenses of the broader cyber ecosystem through increased information sharing and improved technology to defend against Russian threats and address vulnerabilities. Our teams will continue to support nonprofits, journalists and academics both within Ukraine and across allies, allowing those partners to broaden their defense of the information ecosystem. For example, Microsoft recently partnered with International Media Support (IMS) and the Center for Strategic Communication and Information Security within Ukraine to improve rapid information sharing and response between the private sector, NGOs and journalists within Ukraine through a dedicated secure communications hub.

Deter: Microsoft has been dedicated for more than a decade to securing international norms for cyberspace. This winter, our Digital Diplomacy and Democracy Forward teams will work with affected customers and their representative governments to push for unified action to protect our customers’ supply chains against nation state attacks. And we will continue our ongoing efforts to provide actionable threat intelligence to entities targeted or compromised by Russian actors in Ukraine and in the countries supporting its defense.

Finally, for customers, Microsoft encourages the use of strong cyber hygiene and the latest detection and response technology to reduce vulnerabilities to and recover from cyberattacks – a listing of these specific recommendations can be found in the recently released Microsoft Digital Defense Report (MDDR) 2022.[37]

Ukraine has fought a brave defense both online and on-the-ground against a merciless Russian assault. With the help of its partner nations, companies and democratic citizens, we all can ensure that Ukraine and Europe’s infrastructure is protected and democracy resilient in the face of authoritarianism this winter.

No comments:

Post a Comment