Alain Tao

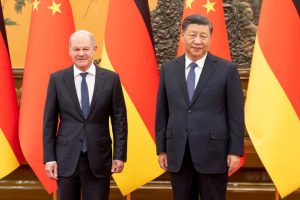

On November 4, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz travelled to Beijing to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Scholz was the first European leader to do so in three years. In these three years, the “Middle Kingdom” Xi presides over has come to resemble more of a “Hermit Kingdom,” thanks to the harsh zero-COVID policy that isolated the nation from the rest of the world. Xi’s administration is also responsible for some of the worst human rights abuses seen in decades, as well as employing economic coercion against countries that disagree with its policies.

In light of Beijing’s autocratic slide, it is no wonder why there are strong calls for a fundamental rethink of Europe’s engagement with the East Asian giant. Therefore, when Scholz announced that he would be accompanied by a business delegation of German CEOs, critics cried foul. It appeared to be business as usual for Scholz, who seemed to intend on continuing the Wende durch Handel (change through trade) policy of his predecessor, Angela Merkel. Many pundits also questioned the utility of such a visit, as Scholz would have been able to meet Xi in mid-November at the G-20 conference in Bali.

But what caused the most uproar was the chancellery’s approval of the purchase of a stake in the port of Hamburg, Germany’s largest, by China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) right before the trip. Six German ministers opposed the deal, including the vice chancellor and the foreign minister, citing national security concerns. Nonetheless, Scholz pushed it through in a move widely seen as a “gift” to his host in Beijing.

Concerns in Berlin were also shared in Brussels. Five days after the Hamburg deal, the European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton commented during an interview that “European governments and companies must realize China is a rival to the EU and they should not be naïve whenever they approve Chinese investments.” When asked about the German chancellor’s trip, Breton advocated for a unified European stance on China, insisting on the importance of a “more coordinated than individually-driven” approach.

Timing Is Everything

The timing of the visit was indeed very poor. The COSCO deal came at a time when the EU was formulating a response to Beijing’s economic coercion of Lithuania. The incident exposed the vulnerabilities of European countries to China’s market leverage. Chinese investments in critical infrastructure are now viewed more than ever before as attempts by Beijing to strengthen its hand against the European Union.

The visit also came in the wake of the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th National Congress, where Xi broke with the party orthodoxy of a two-term limit by securing a third mandate. A high-level state visit in this context would inevitably be perceived as a tacit approval of Xi’s power grab. Even Scholz’s own coalition partner, the market-liberal FDP, came out to criticize the timing of his trip as inappropriate.

The planning of Scholz’s visit also exposed cracks in Franco-German relations. French President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal for a joint visit with Scholz in a show of European solidarity was flatly rejected by the chancellor. When Macron considered making his own trip later in November, Scholz’s visit was unofficially postponed until the French president decided to change the date of his visit to early 2023.

The chancellor’s unwillingness to share the stage could have been one of many reasons why a frustrated Macron suddenly cancelled a Franco-German cabinet meeting slated for October. In a further snub, Macron refused to make a joint press appearance with Scholz following a meeting in Paris. At a time when the EU faces massive headwinds, the bloc can ill afford a deterioration of bilateral ties between its two greatest powers.

No Sino-German Love Affair

But beyond the dubious timing and missteps by Scholz, the main concern was whether his visit signaled a rebooting of his predecessor’s friendly business-centered relationship with China. Scholz’s own party, the Social Democrats, has argued that “systemic rivalry” should define Berlin’s relationship with Beijing. It has also recognized the failure of the “change through trade” approach and is now urging a reduction of dependencies on authoritarian regimes, including Beijing.

The chancellor himself toes the party line, having voiced on several occasions the need to avoid one-sided dependencies on China and undertake a reassessment of Sino-German business ties. Most notably, in an op-ed published just ahead of his Beijing trip, Scholz admitted the existence of “risky dependencies” on China for certain raw materials and technologies. To remedy this, he expressed an eagerness for new partnerships.

German diplomatic visits attest to this desire for diversification. Almost simultaneously with Scholz’s trip, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock embarked on a four-day visit to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, while German President Walter Steinmeier travelled to Japan and South Korea during a weeklong tour. Both visits were substantially longer than Scholz’s lightning 11 hours in Beijing. Furthermore, Scholz himself followed up his brief passage in China with visits to Vietnam and Singapore. These visits were all aimed at increasing bilateral economic ties.

The chancellor is also planning two visits next year to China’s biggest regional rival, India, with whom he has worked to expand cooperation. These developments signal a clear break with the Merkel-era Asia strategy, which placed greater importance on China.

Regarding the COSCO Hamburg deal, it was more a case of unfortunate timing rather than a purposeful accommodation of Chinese interests. The original agreement between COSCO and the port’s operator, HHLA, was for a 35 percent stake in Container Terminal Tollerort (CTT), the smallest of Hamburg’s four container terminals. The agreement included a deadline by which the German federal government had to decide whether to approve or reject the deal. The due date was coincidentally three days before Scholz’s trip to China.

In the absence of a decision the deal would have gone through, giving COSCO voting rights over the operations of CTT. However, with the intervention of the chancellery the stake was lowered, giving COSCO no voting rights. Although a rejection of the deal would have sent a strong symbolic message, it would not have prevented a “grave threat” to national security. HHLA has clarified that COSCO is not allowed access to strategic know-how and that it is not accorded exclusive rights or access to CTT, as the terminal remains open to all clients.

But No Sino-German Split Either

Nevertheless, there is still a strong impetus for Berlin’s continued engagement with China, which stems from a variety of factors.

“It was important for Scholz to establish a personal relationship with Xi Jinping,” observed Roderick Kefferpütz, senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), where his work focuses on Germany’s China policy. There are still important areas where Sino-German cooperation is needed, such as climate change and COVID-19. Therefore, direct contact between both leaders remains essential for a working relationship.

“That would have been harder to achieve if Macron had accompanied [Scholz] to Beijing,” judged Kefferpütz.

Indeed, the lack of personal chemistry between Macron and Scholz, as well as a host of disagreements between their administrations, would no doubt have complicated any such plans. In addition, as head of Germany’s executive Scholz is “outranked” by Macron, as diplomatic protocol gives precedence to heads of state. Scholz’s reluctance to be “upstaged” by Macron was therefore not entirely unfounded.

Apart from establishing personal contact, there are hard economic considerations that will slow Berlin’s decoupling from China. Germany and the rest of the EU are sliding into recession this winter as ballooning inflation and high energy prices caused by the war on Ukraine continue to maul the bloc. In parallel, the United States’ trade and monetary policies have put significant pressure on European competitiveness.

Washington’s Inflation Reduction Act has introduced subsidies so generous that many companies no longer see a point in investing in Europe. For instance, battery developer Northvolt has paused its German factory expansion to focus on its U.S. operations. Solar component producer Meyer Burger is launching a factory in Arizona, casting doubts on further investments in its German plant.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has also aggressively raised interest rates to counter inflation, strengthening the dollar immensely while causing the depreciation of the euro and leading to higher inflation rates in Europe. The elevated U.S. interest rates also make investments in dollars more attractive, further incentivizing companies to divert resources to the U.S. market. These developments have pushed leading European politicians to declare that EU-U.S. trade relations are on the brink of crisis.

In the face of such challenges, Germany needs more than ever before to maintain relations with China, its largest trading partner for the past six years. In the wake of the 2010 Eurozone crisis, it was Chinese demand for German exports and cheap Russian gas that helped Berlin reconcile the contradictory goals of lowering the eurozone’s deficit, maintaining a trade surplus, and seeing through financial crisis recovery efforts. Now confronted by a new economic crisis and with inexpensive Russian energy off the table, Berlin simply cannot afford to cut ties with its third biggest export market.

Divisions Within the Traffic Light Coalition

Be that as it may, the necessity of maintaining a cordial relationship with China is not a sentiment shared by Scholz’s coalition partners. Baerbock and Economic Minister Robert Habeck of the Greens party have each announced plans for the release of their respective China foreign policy strategy and China trade strategy. Both have been leaked, revealing measures such as removing incentives for German companies doing business with China and pursuing closer ties with Taiwan.

“There is an internal struggle in the government to shape Germany’s future China strategy,” Kefferpütz observed.

“The publicity angle of leaking China strategies shouldn’t be underestimated,” the MERICS senior analyst warned. Both Habeck and Baerbock wish to pressure Scholz to adopt a harder line on China.

The leak of their strategies conveniently moves the debate on defining Germany’s future relationship with China into the public sphere. As German public opinion is largely unfavorable toward Beijing, a tougher stance by Berlin would probably find strong support among voters. The risk of a public backlash will no doubt corner the chancellery into signing off on measures that it would normally have no appetite for, such as the promotion of an EU investment deal with Taipei.

With this scenario in mind, Scholz was probably anxious to establish a personal relationship with Beijing before his administration officially adopts a more hawkish posture, with his business delegation as an “olive branch” to Xi.

Scholz the Pragmatist

As Ding Chun, director of the Center of European Studies at Fudan University, candidly stated: “One cannot say that Scholz has fully embraced China.” Claims of Scholz cozying up to Beijing lack foundation, as his visit was a fruit of necessity born from the mind of a pragmatic leader. And results would suggest that his pragmatism has partly paid off.

In a major public relations coup for Scholz, he successfully convinced Xi to voice his opposition to the use of nuclear weapons, a clear rebuke of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling over Ukraine. Scholz also managed to persuade Beijing to approve the use of BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccine by foreign residents, a significant step toward its release to the broader public, after plans for domestic distribution were abruptly halted last year.

Keeping in line with EU policy, Scholz committed with Xi to more collaboration on the management of global supply chains, global food supply, public health, and climate. At the same time, the chancellor expressed his concerns over human rights in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, while also advocating for fairer market access and intellectual property protection for German businesses operating in the People’s Republic.

With his brief visit to the Middle Kingdom, the German leader has succeeded in setting the tone for subsequent visits by European leaders. For instance, during European Council President Charles Michel’s visit to Xi in December, he touched upon the same themes as Scholz: human rights, unequal market access, use of nuclear weapons, and vaccine distribution. Similarly, when Macron heads to China in January 2023, he will also be heading a business delegation of French CEOs.

In a move striking a careful balance between risk and reward, Scholz flying to Beijing under a hailstorm of criticism has earned him the ability to shape Europe’s coming engagement with the world’s second-largest economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment