John S. Van Oudenaren

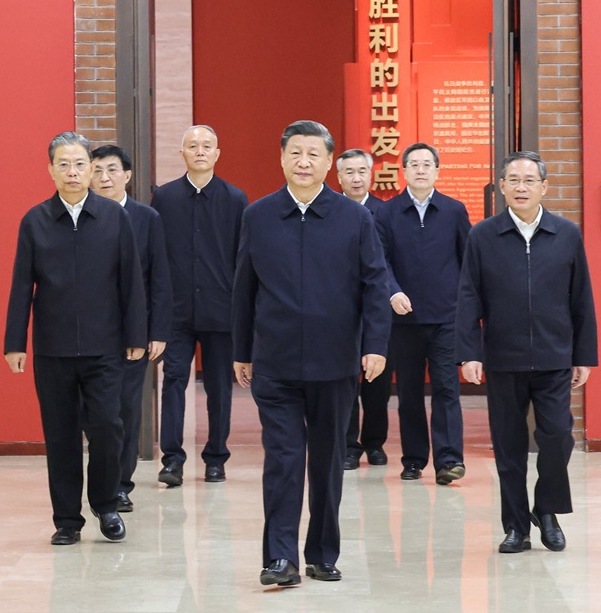

Days after his dominant showing at the 20th Party Congress, General Secretary Xi Jinping led the newly appointed Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) on a visit to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) base of operations in the War with Japan and the Chinese Civil War in Yan’an, Shaanxi (Xinhuanet, October 27). A key theme of the visit was that the CCP’s achievement of political unity in the Yan’an era (1935-1948) enabled it to overcome much stronger foes. The leadership toured the site where the Seventh Party Congress was held in mid-1945 following the “Yan’an Rectification Movement” in which Mao consolidated control of the Party and established Mao Zedong Thought as dogma. The first excursion of a new PBSC is significant as it highlights the leadership’s areas of emphasis for the coming half-decade. Xi opted to visit Yan’an after a Party Congress in which he disregarded many long-held norms concerning leadership turnover in order to stack the Politburo with allies and protégés (China Brief, October 24). In Yan’an, Xi declared: “I have come here to manifest that the new central leadership will inherit and carry forward the glorious traditions and fine work styles of the Party cultivated during the Yan’an Period, and carry forward the Yan’an Spirit.” He defined the Yan’an Spirit as “adhering to the firm and correct political direction, emancipating the mind and seeking truth from facts, observing the principle of serving the people wholeheartedly, and practicing self-reliance and hard work” (People’s Daily, October 28). In identifying the new leadership with the “Yan’an spirt,” Xi is framing his recent consolidation of power as motivated not by self-interest, but by the imperative to unite the Party in challenging times.

The visit was also a homecoming of sorts for Xi, who reminisced about the seven years that he spent in rural Shaanxi as a “sent down youth” during the Cultural Revolution. Yan’an occupies a special place in Xi’s carefully crafted persona as the “People’s Leader” (人民领袖, renmin lingxiu) (Xinhuashe, April 10). According to the official narrative, rural life forged Xi into a genuine servant of the people, who developed an unshakeable bond with the masses by living among them (CCTV, July 11, 2018). In a 2012 interview, Xi said that “when I came to the Yellow Land at 15, I was lost and hesitant, but when I left at 22, I had a firm mission and was full of confidence” (Xinhuanet, February 14, 2015).

The Death of Collective Leadership

The 20th Party Congress effectively obliterated the collective leadership model that defined elite politics in China in the post-Mao era. The conditions that sustained this model, absence of a personality cult around the top leader and a modicum of factional balance in the top leadership, no longer exist. Deng Xiaoping, a Cultural Revolution survivor, believed that “China’s future depends on collective leadership” to forestall the return of a Mao-style, personalistic dictatorship (Qiushiwang, July 31, 2019). The final demise of collective leadership was epitomized by the humiliating removal of former General Secretary Hu Jintao from the Great Hall of the People on the final day of the Party Congress (CNA, October 24).

Debate has ensued over the cause of Hu’s indecorous ejection. Regardless, Hu was assuredly in an ill-temper on the final day of the Party Congress. His political marginalization was about to be made public with the announcement of the new 205-member Central Committee, which indicated that Xi is no longer bound by the unwritten “rules” that previously informed Politburo appointments and retirements (Xinhua, October 22). The new Central Committee lineup omitted two PBSC incumbents, Premier Li Keqiang and Wang Yang, which indicated both long-time Hu protégés, would step down a year before reaching the conventionally observed retirement age of 68. In fact, Xi largely ignored the unspoken “(6)7 up, (6) 8” (qishang baxia) retirement norm to keep allies and promote protégés to the Politburo, while nudging his rivals into early retirement (China Times, October 19, 2017). This was further underscored when Xi’s long-time ally, General Zhang Youxia was kept on the Politburo and the Central Military Commission at age 72 (Xinhua Daily Telegraph, October 24). Current Foreign Minister Wang Yi, a lead architect of Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy, was promoted to the Politburo at age 69, and will likely assume the top foreign policy role from Yang Jiechi (China Brief, October 4). Meanwhile, Vice Premier Hu Chunhua, another Hu Jintao protégé, who was long considered a leading candidate for the Premiership and a shoo-in for the PBSC, did not even retain his Politburo seat.

Allies and Protégés

With Xi’s factional rivals sidelined, the Politburo can be divided into two groups: protégés and allies. Protégés owe their elevation to the PBSC entirely to their relationships with Xi. On the contrary, allies, such as ideology chief Wang Huning and CMC Vice Chairman Zhang Youxia, supported Xi’s rise and consolidation of power, but do not derive their status entirely from their relationship with the core leader. For example, both Wang Huning and Zhang Youxia were on the Central Committee before Xi became General Secretary, and Zhang joined the CMC at the 18th Party Congress in 2012, when Xi assumed chairmanship of the supreme military body (Beijing Review, October 21, 2007).

Allies

Unlike his fellow 67-year-old colleagues, ideology czar Wang Huning sidestepped early retirement to retain his PBSC seat. He is likely to become Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the top United Front Work body. It is commonplace for leading scholars in China to advise on policy, but a career academic reaching the top leadership is an anomaly (Xinhuanet, October 25). The former Fudan University Professor, who was coaxed into politics by Jiang Zemin, has played a major role in shaping all three post-Deng leaders’ contributions to Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents”; Hu Jintao’s “Scientific Outlook on Development” and Xi Jinping Thought. Although Wang has relationships with both Jiang and Hu, his unique path to the Politburo renders him an unlikely potential rival to Xi. Unlike most of the other PBSC members, he has never led a province or a ministry, and as a result, he lacks the regional and/or bureaucratic power base necessary to build his own faction. [1]

Xi managed to keep another major ally on the Politburo, disregarding retirement conventions to promote his childhood friend, General Zhang Youxia to the senior Vice Chairman position on the CMC. A unique figure in the PLA, the 72-year old Zhang has been a driving force in implementing Xi’s post-2015 military reforms. As the head of the CMC’s Equipment Development Department (previously the General Armaments Department) during Xi’s first term, he was instrumental in developing civil-military fusion, which seeks to leverage the PRC’s civilian economy to develop advanced military and dual-use technology (Xinhuanet, October 25). Zhang is one of the few PLA officers with direct combat experience, commanding a company during the 1980s China-Vietnam border war, which included participating in the largest border clash of that conflict, the Battle of Laoshan (Netease, October 11; The Paper, March 3, 2016). A life-long solider, Zhang is clearly committed to the professionalization of the PLA so that it can carry out complex joint warfighting operations with the same acumen as the U.S. military.

Protégés

Xi promoted four protégés, Li Qiang, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang and Li Xi to replace the PBSC seats vacated by the early retirements of Li Keqiang and Wang Yang, as well as the expected departures of Li Zhanshu and Han Zheng. When the new PBSC was introduced, Shanghai Party Secretary Li Qiang followed Xi in the official order, which suggests he will succeed Li Keqiang as Premier. In elevating Li Qiang to the number two position, Xi upended another long-held precedent, which is for any would-be Premier to have experience serving as a Vice Premier on the State Council. Li, who was Xi’s chief of staff in Zhejiang from 2004-2007, oversaw the mass lockdowns in Shanghai earlier this year (Xinhuanet, October 25). Although the lockdown generated widespread popular frustration, Li’s dogged implementation of zero-COVID likely strengthened his standing with Xi (China Brief, April 8).

The promotion of Beijing Party Secretary Cai Qi to the PBSC to head the CCP Secretariat, the little known but instrumental body responsible for coordinating the Politburo’s daily affairs, surprised many observers as well. However, Cai benefited from his decades of experience working with Xi going back to their time in Fujian in the 1980s and 1990s (Xinhuanet, October 25). He also recently further demonstrated his value to Xi in running the politically sensitive Beijing municipality during the pandemic and the 2022 Winter Olympics.

Xi also elevated his long-time aide Ding Xuexiang to the PBSC. In his capacity as Director of the CCP General Office, Ding developed a reputation as Xi’s “alter ego” for accompanying the top leader almost everywhere he went. In that role, Xi entrusted Ding with minding the top leadership, assigning “drivers, secretaries and security details to most of the Politburo members and party elders,” as well as “maintaining a surveillance system over both civilian and military leaders, which includes phone-tapping and close monitoring of their out-of-office activities” (China Brief, May 27). It was Ding’s Deputy, Kong Shaoxun, who removed a flustered Hu Jintao from the closing ceremony of the 20th Party Congress (Dake Kang Twitter, October 22).

The final protégé, to make the PBSC is Guangdong Party Secretary Li Xi, who has close family ties to Xi (People.cn, October 25). Li has already been confirmed as Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) Standing Committee. Placing a loyal follower atop the party’s top internal discipline organ supports Xi’s efforts to maintain tight internal control. In his first speech, Li Xi stressed the need for the CCDI to implement the spirit of the 20th Party Congress through strict governance and rigorous intra-party supervision (Xinhuanet, October 26).

Conclusion

Xi’s success in stacking the Politburo with allies and protégés, aligns the Party leadership with his overall dominance of political life in China, including the de facto cult of personality that now surrounds the “People’s Leader” (Xhby.net, October 14). Political dominance may enable Xi to temporarily paper over some of the present difficulties now facing the PRC, but it will not obviate indefinitely the array of daunting challenges facing Beijing. The new leadership must resuscitate the economy even as it sustains a “dynamic zero-COVID” policy, which has limited pandemic deaths but has also been a major drag on growth. Simultaneously, the PRC is seeking to strengthen overall national security and attain greater financial, technological and resource self-sufficiency, in order to insulate itself from both economic and geopolitical shocks.

In his Party Congress work report, Xi referenced the need to surmount “drastic changes in the international landscape, especially external attempts to blackmail, contain, blockade, and exert maximum pressure on China”— a reference to the challenge posed by intensifying rivalry with the United States and its allies (Gov.cn, October 25). Hence, the overall picture of Xi at Yan’an is of a leader surrounding himself with loyal lieutenants as he prepares for the great struggles to come in the quest to achieve “national reunification” and the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

No comments:

Post a Comment