Niels Graham

As Chinese leader Xi Jinping kicks off his third term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the economy that greets him today is vastly different than the one that saw him ascend to his role a decade ago. The decisions he makes during this new term risk reducing the Chinese economy by as much as five trillion dollars over the next five years, with potentially devastating effects for global growth.

When Xi became China’s leader in 2012, he inherited a nation of newfound wealth growing at a rapid pace. Expanding at an average pace of around 7 percent a year, the Chinese economy nearly doubled in size over the course of Xi’s first two terms.

Now, the situation is markedly different. For the first time since 1989, China will miss its annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth target. Officially, Beijing points to the sweeping COVID-19 restrictions it has implemented across the country to explain the slowdown. However, deceleration in growth prior to the start of the pandemic and economic crises including a meltdown in the property sector, distressed local government finances, and rising youth unemployment suggest that the slowdown may have deeper roots.

As questions mount around China’s economic performance, new research from the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group’s China Pathfinder explores whether the growth slowdown is truly a temporary blip caused by Beijing’s pandemic response or a sign that China is splitting from market thinking.

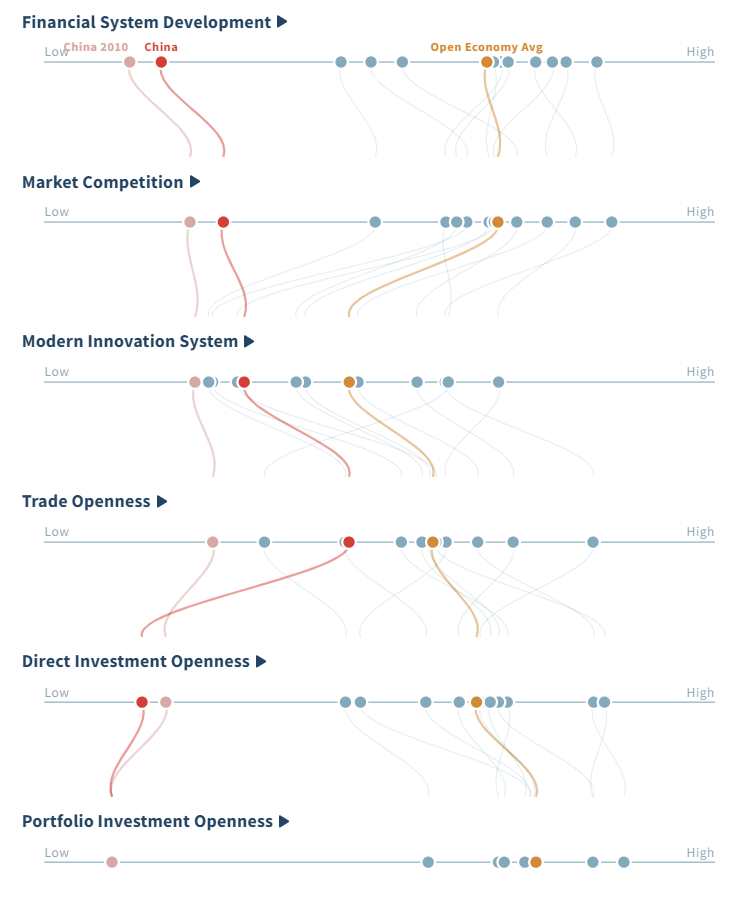

In evaluating China’s progress, the data—spanning from 2010 to 2021 and covering financial system development, market competition, trade openness, moves toward a modern innovation system, direct-investment openness, and portfolio openness—shows that China’s economy has unequivocally converged with open market economy norms, although the progress has been uneven. Though China remains behind economies such as Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, it has seen significant improvement in innovation and trade, with modest improvements in financial system development. In contrast, its progress in implementing reforms that support market competition and investment openness has been more piecemeal.

Source: China Pathfinder

Source: China PathfinderLooking forward, China’s progress in trade openness and innovation will likely persist. The Twentieth Party Congress signaled no major changes in China’s economic-policy direction and Xi has pointed to trade and innovation as priorities for his third term. Still, there are gaps in that progress, suggesting deeper structural weakness that cannot be overcome quickly—putting China at risk of backsliding.

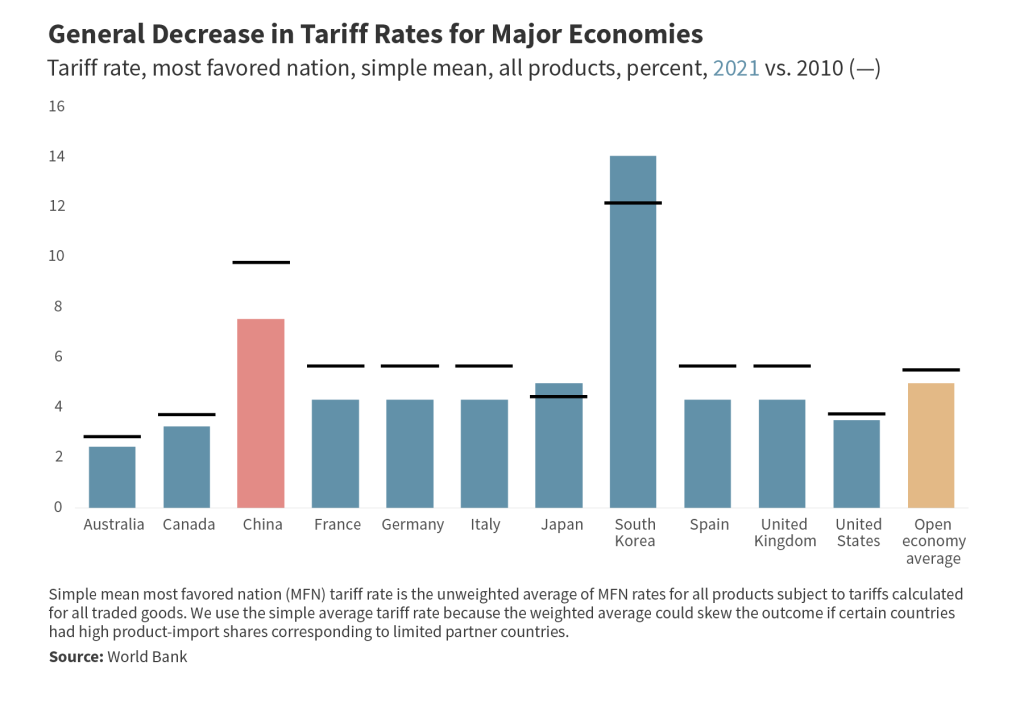

Trade openness

Over the past decade, Beijing has focused on integrating its economy with global trade flows of goods. It has lowered the tariffs it applies to imports—going from a mean tariff rate of around 10 percent in 2010 to 7.5 percent in 2021—and has increased the portion of global goods that flow through its economy from around 9 percent in 2010 to 12.5 percent in 2021. As Beijing follows an export-led growth model and pursues new trade deals, such as a possible deal with Uruguay, China’s barriers on trading goods will continue to fall through Xi’s third term.

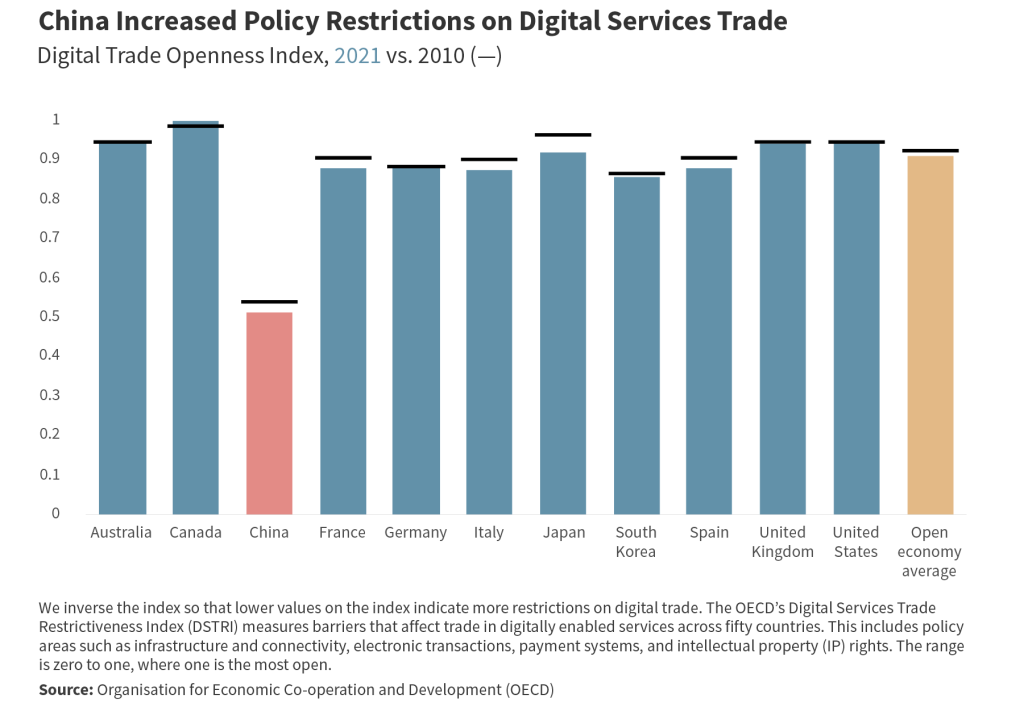

However, China’s trajectory on trade liberalization has not been so unequivocal. Non-tariff barriers on goods, services, and digital trade (alongside subsidies and Beijing’s refusal to adjust exchange rates to correct its balance of payments) muddle the story of China’s progress. Beijing’s restrictions on digital trade are of particular note given the growing significance of digital trade for advanced economies. China’s score in this area has worsened since 2014, a reflection of additional restrictions Xi imposed over the past eight years.

Despite Beijing’s trade reforms, exports no longer represent the engine of growth they once were for China. As the rest of the world teeters towards recession, near-term demand abroad for Chinese goods is weakening, and a long-term focus on export-driven growth cannot supplant a shift towards domestic consumption. Beijing still needs to boost the country’s own household consumption for China to transition toward a sustainable growth model.

Toward a modern innovation system

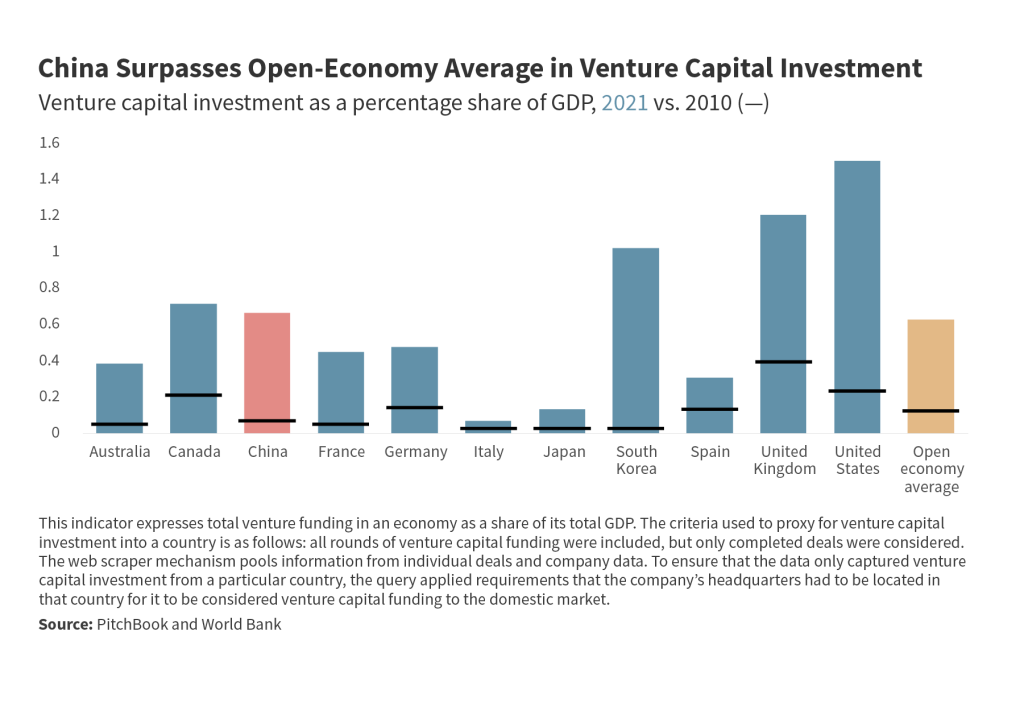

Like with trade, Beijing has also implemented policies to improve its innovation economy throughout Xi’s first two terms. As a result, China now scores higher than Spain, Italy, and Canada in innovation, according to China Pathfinder. This is primarily driven by boosts in China’s research and development (R&D) spending across both the public and private sectors. China’s R&D spending relative to GDP increased from 1.7 percent in 2010 to 2.4 percent in 2021, though it remains below the open-economy average and significantly below high-tech powerhouses such as South Korea, Japan, and the United States. This increase has been driven in large part by the private sector. Venture capital in particular has taken off in the past decade as China prioritizes the development of disruptive new technologies such as artificial intelligence, 5G and 6G telecommunications equipment, and biotechnologies.

However, this progress comes with caveats. Through government guidance funds and subsidies, the state still largely determines where innovation takes place. Recent moves such as Beijing’s crackdown on tech companies also risks undermining the innovation gains that China has made in recent years.

The past decade has also seen China turning away from the United States and European Union as partners on innovation and opting to look inward instead. Venture capital once again offers an example: When Xi first took power in 2012, Chinese companies represented 65 percent of investors in venture funding rounds for other Chinese companies. In 2021, the most recent year with complete data, they represented 82 percent of total investors. This trend will likely continue with Xi emphasizing the importance of greater “self-reliance and strength in science and technology” during the party congress. This is not without risk: Weakening foreign investment in China could diminish the country’s innovative potential by squeezing funds and reducing opportunities for international collaboration.

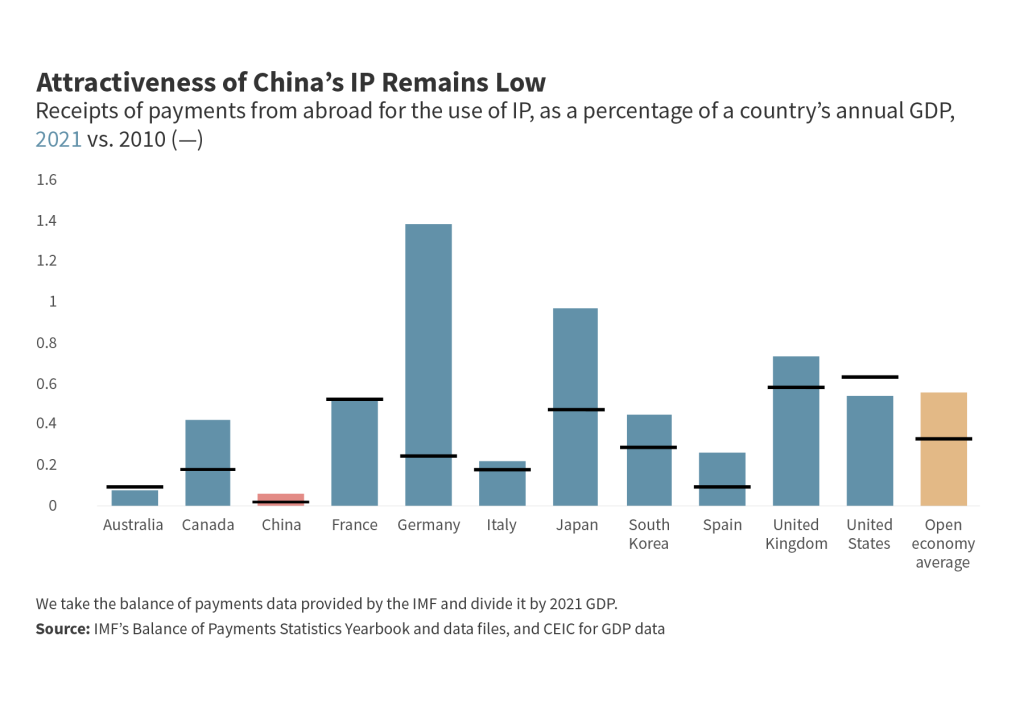

Despite China’s progress in R&D spending, the country still lags behind the open-market economy average in measures of innovation quality. For example, in 2021 the payments China received for foreign use of its intellectual property only reached around one-seventh the average amount that an open-market economy receives when adjusted for GDP; that implies that Chinese intellectual property remains unattractive relative to that in other leading economies. China’s commercial aviation sector shows how China’s R&D spending doesn’t line up with the quality of its output: The sector has swallowed extensive amounts of capital and resources over the past twenty years with little to show for it.

A statist shift

China’s reform progress during Xi’s first two terms in other economic areas tracked by China Pathfinder has been lackluster. Furthermore, China’s progress toward market economy norms slowed in most areas, including innovation, in 2021. Beijing’s reforms to develop its financial system and boost market competitiveness have stagnated, and its openness to both portfolio and direct investment has decreased since 2020. The Twentieth Party Congress showed no signs of bucking this trend, especially since for the first time since 1989, the Politburo Standing Committee is entirely composed of loyalists to the party leader. This will have dangerous consequences for China’s long-term growth rate.

China’s market reforms should not be seen as concessions to the West. Rather, they are the bedrock of China’s own economic growth prospects. There is a chance the damage done to China’s GDP growth prospects by its property sector collapse and its adherence to its zero-COVID policies will compel Beijing to return to the pro-growth reform path the CCP outlined in 2013 but largely abandoned during Xi’s second term. Unfortunately, the fear—and the more likely outcome—is that Beijing will instead fall back on statist solutions that have defined the economic direction of the end of Xi’s second term. This could mean a long-term GDP growth rate of around 2 to 3 percent, which is a far cry from the 5 percent analysts forecasted prior to the pandemic. The result: a Chinese economy five trillion dollars smaller than projected by the end of the decade, with somber implications for global growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment