Jude Blanchette and Gerard DiPippo

Speculation has increased over the past several years that Beijing is accelerating plans for an invasion of Taiwan. While there is little doubt that Beijing seeks to fully annex Taiwan into the People’s Republic of China (PRC) one day, questions remain about the timing and methods that China might use to achieve this goal.1

There are several reasons Beijing might undertake a military campaign against Taiwan:

1. Long-standing territorial and national identity aspirations

2. Xi’s own personal ambitions and sense of legacy

3. Addressing a perceived threat to its own security stemming from deepening U.S.-Taiwan defense cooperation

4. Responding to perceived provocations from Taiwan, specifically a formal declaration of de jure and permanent independence from the PRC

While a great deal of commentary and analysis has explored how the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might undertake a military campaign to annex Taiwan, a critical—yet underemphasized—question remains regarding the types and magnitudes of costs Beijing would pay for such actions. Nearly all discussions of China’s potential invasion of Taiwan ignore the economic and diplomatic costs of such a move, make unrealistic assumptions about what China could achieve (including technological and economic gains), or otherwise minimize the challenges that China would face if an invasion of Taiwan were successful.

The below analysis is an initial exploration into some of these potential nonmilitary consequences for China. It does not seek to prove or disprove Beijing’s true intentions and timelines toward Taiwan, nor does it claim to know how Chinese leader Xi Jinping is assessing the risks and rewards of an invasion. Rather, it highlights costs that Beijing would likely face if it successfully invaded Taiwan, based on plausible assumptions of how China, Taiwan, the United States, the international community, and global investors would react.

Specifically, this brief looks at three distinct phases of a possible Chinese attack:

1. The period leading up to an attack

2. The period between the initial phase of an attack and the end of major conflict

3. The period following a successful PLA invasion

To keep the analysis focused on how a successful invasion by the PLA would impact China’s economic, diplomatic, and political circumstances, this brief intentionally remains nonspecific about the type of attack or invasion it might launch. At a minimum, this analysis assumes that it would include the direct use of lethal force by the PLA’s air, land, and sea capabilities to defeat and subdue Taiwan’s military and to depose the civilian political leadership on the island. It also assumes that the U.S. military would intervene, but its actions would be limited and ultimately unsuccessful in halting the Chinese invasion. And it further assumes that no nuclear weapons would be used. Such assumptions are not predictions of actual outcomes, but rather necessary simplifications adopted so this brief can focus on the issue of costs associated with a relatively smooth path to military victory for Beijing.

Any conflict in and around Taiwan would entail major economic, financial, diplomatic, and reputational costs for Beijing, both directly and indirectly. Even if China “won” in the military domain and thus accrued additional regional military benefits, its economic and diplomatic position would likely be substantially worse off. Simply put, China would have gained Taiwan but sacrificed its larger ambition of becoming a global and comprehensive superpower. This is the very definition of a Pyrrhic victory:Even absent U.S. intervention, any conflict initiated by the PRC would have immediate and dramatically negative effects on China’s ability to import and export goods, on its domestic financial markets, on business sentiment, and on the exchange rate of its currency.

China’s costs would significantly increase if the U.S. military intervenes meaningfully, even if delayed by several days or even weeks. The blunt geographic truth for China is that conflict in the Taiwan Strait would occur directly off the shore of its most economically important and populated provinces.

Even supposing Chinese troops could overcome Taiwan’s defenses, they would then occupy an island inhabited by a hostile population with a shattered local economy, including its semiconductor sector, while China itself would face severe economic and diplomatic repercussions.

This exercise is necessarily speculative and requires many assumptions. Perhaps the most important ones are that Taiwan offers at least some resistance and that U.S. leadership can effectively organize some semblance of an anti-China coalition among advanced economies. In addition, forecasting the effects of major discontinuities requires considerations for societies’ potential reactions under stress rather than under normal conditions. History suggests that major crises can trigger or inspire rapid shifts in consensuses based on reevaluations of national, political, or cultural priorities that can supersede economic logic.

The United States has compelling strategic reasons for deterring China from attacking Taiwan. This exercise is not intended to suggest that losing Taiwan to the PRC would be a positive outcome for Washington. Rather, the key point is that even in this dire scenario, China would still likely be the country that most suffers diplomatically and economically.

Estimating the effects of such a conflict with any precision is extremely difficult, in part because there is no analogous historical case upon which to draw. The world’s two largest economies might be at war with each other. Global supply chains are far more integrated now than before World War II—or even World War I, which ended the first era of globalization.2 The disruptions from the Russia-Ukraine war are not a good proxy because Russia’s economy is far smaller than China’s, the conflict and Western response have not stopped key Russian exports, and Western powers are not directly engaged in combat.

Nonetheless, this brief concludes that the implications of a PRC attack on Taiwan would be cataclysmic for China, the United States, and the world. Simply put, any attempt to achieve “reunification” through force is likely to fracture global geopolitics and economies far beyond today’s “partial decoupling” trends and preclude any long-term “national rejuvenation” for China’s economy.

Phase One: Pending Chinese Attack on Taiwan

Beijing’s preparation for an attack on Taiwan would likely alert foreign governments and investors to the impending conflict, but the signals would not be entirely clear. These actions would include measures to mobilize its forces, insulate its economy and financial system, ready its population, and prepare the diplomatic space for a conflict that Chinese leaders might assume will entail enormous costs for the Chinese Communist Party. While Beijing would strive to obscure its intentions in some scenarios, the required military, economic, and political preparations would be at least partially detectable to the international community. Such observable signals might include stockpiling of munitions, a freeze on military demobilizations, and an intensification of bellicose propaganda.The United States would warn of China’s military intentions, hoping to rally allies and deter Beijing. The effectiveness of such warnings would depend on the strength of U.S. leadership, the state of Washington’s diplomatic relations with third countries, and the credibility of U.S. intelligence. Beijing would likely proceed toward an attack in a manner that clouds or frustrates U.S. efforts to assign blame to China, such as by claiming that Taiwan provoked Beijing by crossing red lines or even that Taiwan’s military attacked Chinese territory or a Chinese asset.

Some U.S. allies and partners would join Washington in warning of Beijing’s intentions. U.S. allies—most likely including Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom—would coordinate planning for steps that could deter China. However, even among allies, the bar for assuming an attack on Taiwan is imminent would be high. The intensity of allied responses would thus largely depend on the credibility of U.S. intelligence, the strength of U.S. government statements and actions, and Taiwan’s own demonstrations that it took the threat seriously. This would include military preparations and the threat—or perhaps use of—economic sanctions on China to deter military action. On the other hand, the United States and its allies would be wary of acting too drastically, which might escalate the crisis, including by triggering responses from Beijing, precluding off-ramps for China, or damaging the global economy.

Other governments would be slow to respond. Some might believe Beijing’s actions are mere saber rattling, as some Western governments did ahead of Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine despite clear warnings from Washington. Some leaders would hesitate because they want to avoid taking disruptive emergency measures not yet seen as justified by their uncertain or oblivious polities. Other leaders would try to avoid committing themselves to either side in a conflict. Behind the scenes, Beijing would likely be using all its diplomatic channels to pressure third countries to remain on the sidelines.

International firms and investors would need to make important early decisions in an environment of extreme uncertainty. Financial markets would be the first to respond, with strong downward pressure on Chinese assets and the renminbi’s exchange rate. Many foreign investors would assume the crisis will harm business sentiment in China and, even if resolved, at least incrementally slow the economy. Direct investors would be slower to respond than portfolio investors.Because Beijing’s true intentions, including the scope and scale of a possible attack, would not yet be entirely clear, many firms operating in China, Taiwan, or the broader region would adopt a “wait and see” approach. Global headquarters would be looking to in-country staff for information and updates—though even staff in China and Taiwan would be struggling to interpret events. Because the costs of shifting supply chains or divesting from China could be substantial, many companies would delay making drastic decisions in the hope that a crisis never materializes.

Phase Two: Period of Conflict

A conflict over Taiwan would devastate the global economy, but the costs would be especially high for China. The negative economic impact would be felt as soon as hostilities begin. Commercial shipping through the war zone and nearby ports would collapse, supply chains for many goods would seize up, and financial markets would panic—potentially even more so than during the 2008 global financial crisis. Beijing would likely impose emergency economic measures such as even stronger capital controls, selling Chinese assets abroad, stockpiling emergency supplies, suspending critical exports, rationing key imported goods, or restricting foreign travel.3 Early resistance by Taiwan’s military would compel China to take economically disruptive measures to protect its military assets in its eastern provinces and population centers from air or missile attacks from Taiwan or U.S. forces. Even a minimal level of U.S. military involvement would significantly disrupt this vital region.The two most important determinants of the war’s intensity and duration—and thus economic impact—would be the degree to which Taiwan resists and whether the United States is engaged militarily. Neither condition is certain, but both are probable. To assume Taiwan would not resist, one must have a bleak view of Taiwan’s civil society. To assume the United States would not engage militarily, one needs to at least assume that Beijing’s military operations would be extremely effective and quick while also not targeting U.S. forces in the region. Beijing would have an official pretense for any military action, but unless Taiwan took reckless actions, such as declaring independence, it is unlikely that leaders in Washington and other Western capitals would find them convincing. In the early days of the conflict, global firms and investors would assume that U.S. military intervention and general escalation pose high risks, absent extremely unlikely statements by Washington that explicitly disavow Taiwan.

A 2016 study by the RAND Corporation estimated that a year-long war between the United States and China would reduce China’s GDP by 25–35 percent and U.S. GDP by 5–10 percent. However, the study did not examine the implications for global supply chains or estimate effects from sanctions, infrastructure damage, or cyberattacks.4 Given China’s subsequent economic growth, the economic damage ratios now are probably somewhat more in China’s favor, but the overall costs (considering all factors) could be considerably higher. A war would have an immediate impact on the three Chinese provinces nearest to Taiwan—Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang—which together account for 22 percent of China’s GDP and 17 percent of its population. Damage would not be limited to coastal provinces, however, because interior provinces are part of an intricate network of domestic supply chains.

Most maritime trade and air freight within range of the war zone would be disrupted. International shipping and logistics firms would try to reroute traffic around the conflict zone and would avoid entering ports in or near Taiwan. Shipping insurance premiums would surge. Chinese ports accounted for roughly 40 percent of shipping volume among the world’s 100 largest ports in 2020; six of China’s largest ports are near Taiwan and would likely be directly impacted by a Chinese attack. Nearly half of the global container fleet and five-sixths of the largest ships transit through the Taiwan Strait, most of which would be rerouted.5 A complete disruption of China’s trade would reduce global trade in added value by $2.6 trillion, or 3 percent of world GDP—and this figure, based on peacetime valuations of global supply chains, only captures the first-order effect on trade.6 In the short term, however, existing inventories of goods or supplies would mitigate the effect on global firms and consumers.

Even in the early stages of a conflict, multinational corporations (MNCs) would face significant pressure to begin unwinding operations in China. Managers’ foremost consideration in the hours and days after a Chinese attack would be employee safety, and many foreign MNCs would seek to exfiltrate foreign passport holders. Companies operating near the eastern coastline would likely halt operations even if they encounter no supply chain disruptions. MNCs exporting from or sourcing parts from China might try to shift production or inputs to other locations, although this would be expensive, and there would be competition from other firms doing the same thing with limited alternative capacity. MNCs operating in China for access to its domestic market would be the least likely to try to pull out because direct investments, such as factories and retail locations, are difficult to liquidate in a crisis. Such firms might conclude that even in dire scenarios, the Chinese market would still be enormous—at least after the conflict. However, they would fear the appropriation of their assets by Chinese authorities and the reputational costs in other markets if they remain in a China hostile to the West.

China would face significant capital-flight pressures and a massive selloff of Chinese assets. Chinese citizens, companies, and investors—as well as foreign firms—would seek to jump the queue and avoid having their international capital ensnared by Western sanctions. While China already maintains stringent capital controls, the central bank would likely issue additional unofficial “window guidance” to China’s major state banks, directing them to halt outgoing transfers. Unofficial and illicit channels exist for motivated parties, but they are relatively narrow owing to regulators’ efforts to diminish their effectiveness. In addition to selling off onshore Chinese stocks, many investors would also dump their holdings of Chinese stocks listed on overseas exchanges. The exchange rate of the onshore and offshore renminbi would plunge, necessitating heavy interventions by the central bank to arrest the slide. As during other periods of heightened risk, global investors would flee to assets perceived as safe, especially U.S. Treasury securities and U.S. bank deposits.

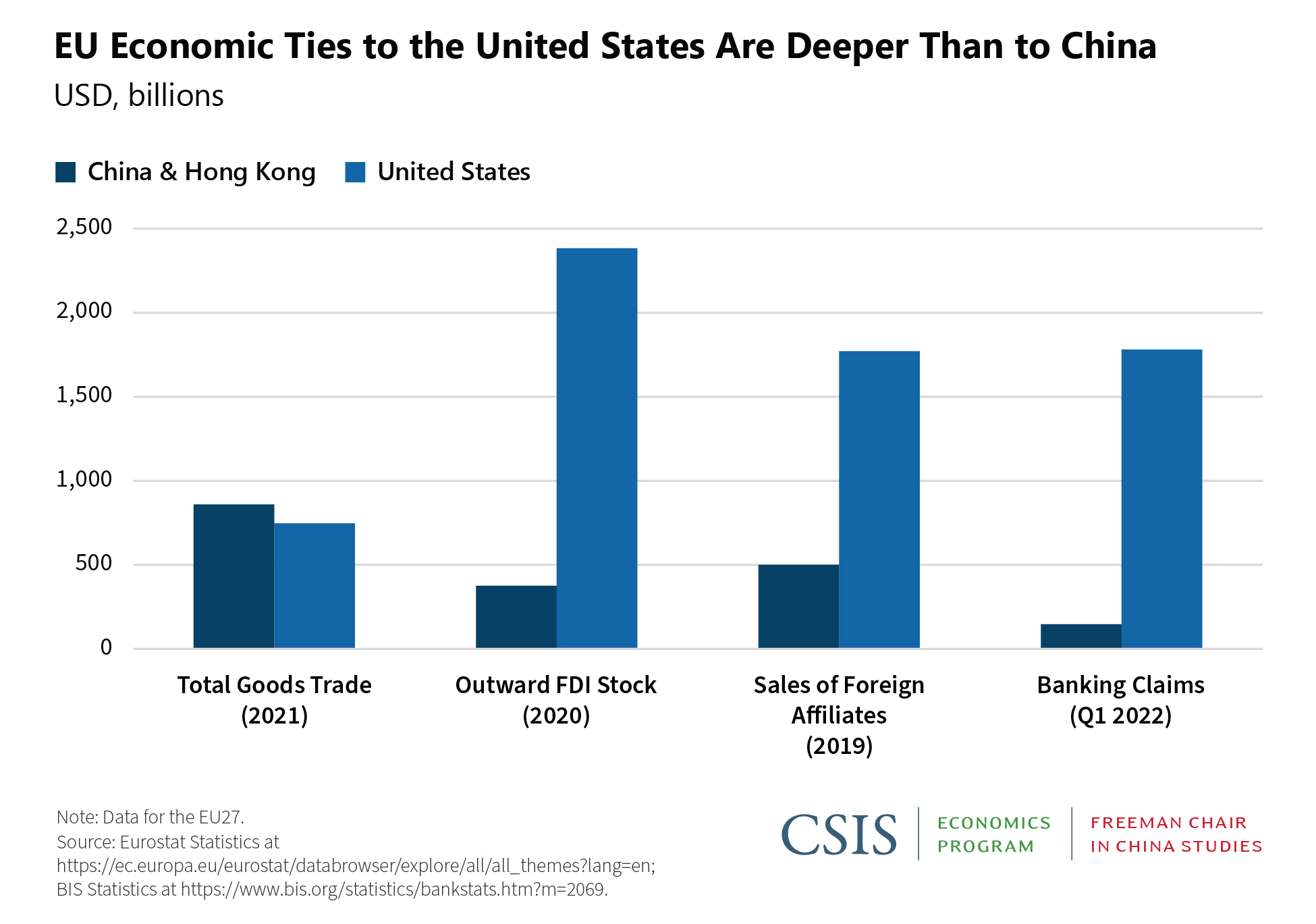

The United States would impose at least some economic sanctions on China in any scenario. But if U.S. forces were engaged, the sanctions would be severe, and Washington would probably coordinate with—or even compel—major allies to join such sanctions. U.S. politicians and the public would likely not tolerate continued direct trade or investment with China if U.S. forces suffer even a low number of casualties fighting Chinese forces, although indirect economic linkages would remain. Financial sanctions on major Chinese banks would have a devastating economic impact, including for U.S. firms and consumers. The expected costs of such actions suggest they would only be used in full once a conflict breaks out and the United States becomes militarily involved. If U.S. personnel start dying and the public sees bloody images of China’s attack on Taiwan, Western sentiment would likely turn swiftly and decidedly against China. A Western sanctions coalition could coalesce quickly, as happened after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in part because of lessons learned and coordination mechanisms established in response to the sanctions against Russia.Major U.S. allies, even if not engaged militarily, would likely support Washington’s efforts to punish China economically. While China’s market and supply chains are critical for many international firms, overall, the United States is even more important as a consumer market, investment destination, and financial market. The European Union’s—even just Germany’s—economic and financial ties to the United States are far deeper than those with China. Perhaps more importantly, Europe’s political, cultural, and security ties with the United States would present European leaders with a binary choice they might otherwise hope to avoid. Washington would exert significant pressure on its allies to join its sanctions efforts; if the United States were engaged militarily, those requests might become ultimatums, which Western leaders would need to weigh against the expectation that China’s economic growth and liberalization has peaked.

Taiwan’s economy would be shattered and cut off from most trade, losing the ability to export the majority of the world’s semiconductors and microchips. Much of its infrastructure would be damaged during combat or from sabotage by local actors, and Taiwan’s ports would be well within the combat zone. This would halt Taiwan’s microchip exports, of which roughly 60 percent go to China as inputs into electronics that are then exported to the rest of the world.7Global supply chains for consumer electronics would be particularly damaged. China’s exports of consumer electronics, such as smartphones and laptops, have accounted for nearly 40 percent of the global total since 2014.8 Because of shipping disruptions and possible suspensions of trade with advanced economies, China’s domestically produced microchips would also probably not be exported.

Phase Three: The World After

Even if the PLA were successful in seizing and holding Taiwan, Beijing would still face enormous economic, diplomatic, and political challenges. The only plausible pathway to mitigating these challenges would be for China’s military operations in Taiwan to be quick (to shorten the window Washington has to respond) and clean (to minimize fighting and damage, including civilian casualties in Taiwan), as well as avoid triggering an international backlash, particularly from advanced economies. More realistically, an attack on Taiwan—even a successful one—would result in some level of U.S. military involvement, a direct response from Taiwan’s military and people, and international outrage.

Taiwanese military personnel drove a CM-25 armored vehicle across the street during the Han Kuang military exercise, which simulated China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) invading the island on July 27, 2022, in New Taipei City, Taiwan.

Photo: Annabelle Chih/Stringer/GettyImagesChina would occupy a new but significantly damaged and isolated “special administrative region,” which would face a severe economic contraction and be expensive to subdue, police, and rebuild. Chinese military and security forces would contend with a restive population, even assuming local resistance is not prolonged. Reconstruction costs would be high and absorb much of Taiwan’s remaining fiscal capacity. The public on the mainland might object to spending Chinese resources to occupy and rebuild Taiwan, given that the island is nominally more developed than most of the mainland and its people are considered hostile. Chinese leaders probably would have planned for the post-war environment based on optimistic assumptions, in part because experts and planners would have been reluctant to suggest that Taiwan’s population is sincerely opposed to “reunification.”

Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, including the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC), would be severely damaged and unable to resume production of cutting-edge microchips. Assuming TSMC is not affected during combat or destroyed by saboteurs, its seizure by Chinese forces would only give China a snapshot of its technology in an otherwise fast-moving global industry. Beijing would also need to coopt or compel TSMC’s employees to continue working for the firm. Furthermore, TSMC relies on foreign inputs, including for chip designs and chip-manufacturing equipment. The governments of key advanced economies would likely impose export controls on those inputs, even if this means losing access to leading-edge fabrication capabilities. Foreign firms reliant on TSMC for production would no longer consider its Taiwan facilities reliable even after reconstruction. However, TSMC’s overseas assets might continue operating, assisted by TSMC staff who escape Taiwan and perhaps after being acquired by other firms.

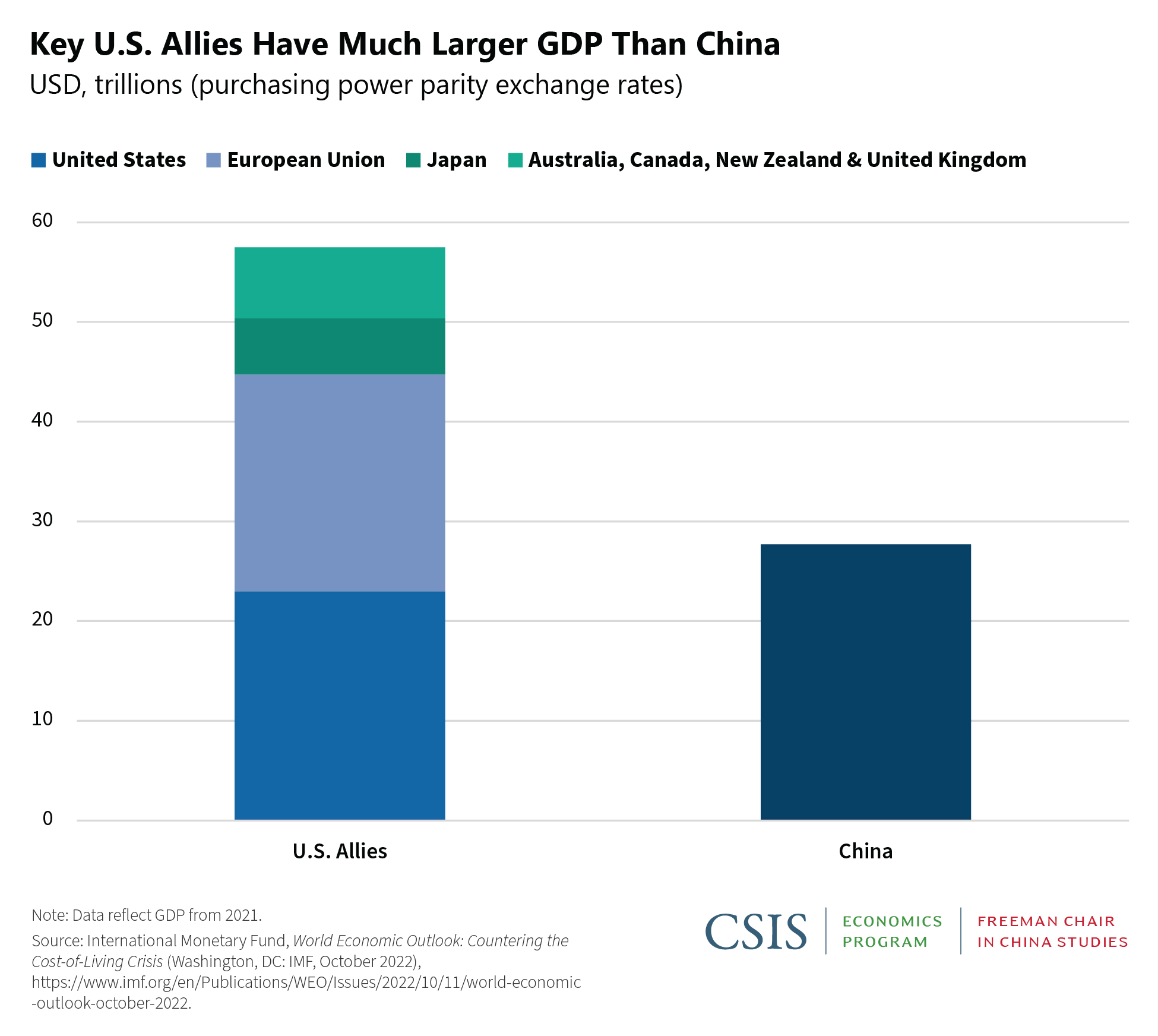

China’s economic and diplomatic relations with advanced economies would significantly deteriorate. Western sanctions and export controls on China would probably persist for months or perhaps years after a conflict, even if U.S. military forces are defeated. In Washington, Tokyo, and some European capitals, there would be little to no political appetite to resume normal economic relations with a belligerent China. Both sides would suffer, but China would suffer more. In 2021, the Group of Seven (G7) economies—a reasonable proxy for the U.S. alliance network—had a collective GDP 65 percent larger than China’s, even at purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates favorable to China, and directly absorbed 41 percent of China’s exports.9 China has little prospect of eliminating its key external economic dependences—technology, commodities, and the U.S. dollar—in the medium term. After a conflict, China would largely maintain access to commodities from emerging markets and developing countries. However, China would struggle to overcome technology export controls and sanctions based on the global dollar network, upon which its remaining trading partners would also remain reliant.

China’s periphery would become increasingly hostile. Any Chinese attack on Taiwan would provoke significant anxiety among China’s neighbors. If the United States were perceived to have intervened aggressively, even if ultimately unsuccessfully, U.S. credibility as a security partner would largely remain intact, if somewhat bruised. On the other hand, if U.S. intervention were seen as halfhearted, countries might put less stock in Washington as a security guarantor, and some might develop their own capabilities, including nuclear weapons, to deter China. Either way, China’s aggression would likely galvanize a surge in military spending and pronounced bandwagoning against Beijing by Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India, but also Vietnam and the Philippines. Most other emerging markets or developing countries, however, would probably try to remain neutral.

Annexing Taiwan would likely give Xi Jinping an initial bump in public approval, but the mounting costs of “state-building” would erode overall domestic confidence in the CCP. Propaganda organs would seek to contain criticisms of the invasion, but the proximity of the conflict would make it difficult to obscure the likely military casualties. Such efforts would be further undermined by the vast network of overseas Chinese nationals with unfettered access to information on the invasion’s course and consequences. Beijing would probably feel forced to use terror and repression to subdue pockets of resistance (real or imagined) in Taiwan, and reports of such atrocities would inevitably filter through to the mainland population. An invasion of Taiwan and the associated occupation phase would also distract Beijing from addressing China’s pressing domestic agenda and economic headwinds. To take control of the narrative and tamp down on any domestic unrest (again, real or imagined), the CCP would feel compelled to flex all its coercive muscles, and thus China would enter a new and more protracted phase of its police state.

China’s economy would be on a wartime footing, and its hope of achieving high-income status would be severely diminished. Beijing would struggle with China’s overburdened fiscal system and state-sector debts amid capital outflows—and could face a systemic financial crisis. MNCs would expect Western sanctions and export controls to persist, while also forecasting far less potential from the Chinese market, and thus would generally maintain lower exposure to China. Foreign MNCs operating in China would fear asset nationalization, and even MNCs who want to remain or reinvest in China would face a Chinese government that scrutinizes companies representing “hostile” Western countries. China’s outbound investments and lending would be constrained. Amid draconian capital controls and a loss of foreign investor confidence in China’s trajectory and reforms, the renminbi would not substantially internationalize.

Conclusion

The purpose of this initial exercise is to sketch out some of the likely responses to a Chinese attack on Taiwan and the associated political, economic, diplomatic, and strategic consequences Beijing would face. The conclusion reached is stark: China would court disaster if it launched an invasion across the Taiwan Strait. Even under optimistic assumptions about the combat performance of the PLA and the relatively muted or constrained military responses by Taiwan and the United States, there is a precariously narrow path Xi Jinping would need to follow to emerge from the gambit unscathed. Once more realistic assumptions begin to be layered in, the picture becomes dire for the CCP and China as a whole. Equally as significant, any Chinese attack on Taiwan would also have an extraordinary impact on the global economy, especially for U.S. partners and allies in the region.

The key strategic challenge for the United States remains to ensure Beijing never actively contemplates an attack on Taiwan. While it is likely Beijing broadly understands the costs associated with such an action, the increasing isolation of Chinese leader Xi Jinping and the concomitant rise in groupthink in Beijing’s policymaking circles means that one cannot assume Chinese leaders will continue to conduct a sound cost-benefit analysis. It thus remains critical to find direct and clear ways to communicate to Xi Jinping the costs he would face for undertaking any attack on Taiwan.

No comments:

Post a Comment