Fahim Abed

ON A RAINY Saturday morning in May, Hayanuddin Afghan, a former member of a CIA-backed militia that was once his country’s most brutal and effective anti-Taliban force, welcomed me to his new home in a hilly neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

He invited me in through the kitchen, where his wife, who was pregnant with their fourth child, was baking traditional Afghan bread with flour from Aldi’s. The trip downtown to buy groceries was among the greatest challenges of Hayanuddin’s new life in Pittsburgh. It involved hauling heavy bags back home on foot and in multiple city buses, whose schedules were unknowable since he didn’t speak English and had not downloaded the relevant app.

“It is difficult to descend from a very strong position to a very weak position,” Hayanuddin told me. In Afghanistan, “we had value. It was our country, and we were making sense for that country. But now, even our generals and commanders, everyone is in the same position.”

In Afghanistan, it was impossible to talk at any length to members of the secretive commando forces known as the Zero Units. They hunted the Taliban in night raids and were widely accused of killing civilians, including children. But last September, Hayanuddin and his Zero Unit comrades were the beneficiaries of the most successful aspect of the Biden administration’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan: the CIA’s rescue of its allied militias. Their arrival in the U.S. over the last year has cracked open one of the war’s blackest boxes.

My conversations with Hayanuddin and several other militia members yielded new details about the command structure, operations, and final days of shadowy units that were nominally overseen by the Afghan intelligence service but were in fact built, trained, and in many cases fully controlled by the CIA. Their fighters hold clues to many of the war’s mysteries, including how U.S. intelligence engineered and oversaw years of deadly night raids that contributed to the Taliban’s ultimate victory, and how a secret deal between longtime enemies may have hastened the lightning collapse of the Afghan security forces last August.

Celebrated as heroes by their American handlers and some Afghans who oppose the Taliban, militiamen like Hayanuddin were feared and detested by many rural Afghans, who bore the brunt of their harrowing raids. While hundreds of Zero Unit members and their closest relatives made it to the U.S., they left behind extended families who have suffered abuse, imprisonment, and death threats under the new government.

The CIA did not respond to detailed questions about its role in overseeing, evacuating, and resettling Zero Unit members and whether the agency would do more to help militiamen and their families left behind in Afghanistan. “The United States made a commitment to the people who worked for us that we would create a concrete pathway to U.S. citizenship for those who gave so much to assist us over the years,” an agency spokesperson told me in an email. “It will take time, but we never forget [our] partners and are committed to helping those who assisted us. We are continuing to work closely with the State Department and other US government agencies on this effort.”

“With regard to allegations of human rights abuses,” the email continued, “the U.S. takes these claims very seriously, and we take extraordinary measures, beyond the minimum legal requirements to reduce civilian casualties in armed conflict and strengthen accountability for the actions of partners. A false narrative [exists] about these forces that has persisted over the years due to a systematic propaganda campaign by the Taliban.”

Hayanuddin said that he and his comrades took care to avoid harming bystanders during their raids, even using loudspeakers to warn women to stay inside or shelter in basements before the fighting began. “For me, it was like a holy war,” he said. “I was there to target bad guys.” But he also described lingering feelings of rage, guilt, and remorse, and connected his struggle in Pittsburgh to his past. At one point, he wondered aloud if he was being punished.

“Sometimes I can’t control my anger and my anxiety,” he told me. “My heart is so sad, like someone is squeezing it very hard. I don’t know why. Maybe because of what happened back home or what is happening here.”

Reversal of Fortune

I met Hayanuddin last spring, at an Afghan New Year’s celebration in a park in Pittsburgh, where we had both recently settled as refugees. I had worked for the New York Times in Kabul for five years and made many trips to the front lines to report on the Afghan security forces, including in the days before the Taliban captured the Afghan capital last August. I was evacuated with other Times staffers to Houston, where I lived in a hotel for several months before getting a job as a visual journalist at the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review and moving north.

At first, Hayanuddin didn’t want to talk to me. But after several attempts, he grew more comfortable, in part because he thought he was talking about an episode of the war that was closed, and in part because we were both exiles from the same place, trying to start new lives in Pittsburgh while still longing for home.

Hayanuddin had served six years with a unit known as 03, fighting the Taliban across Afghanistan’s southern deserts from his base in a compound previously occupied by the one-eyed former Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar. U.S. special operators had commandeered the property when they arrived in Kandahar in 2001 and turned it into a redoubt for American and Afghan intelligence forces. With hundreds of other Zero Unit fighters, Hayanuddin crossed shifting front lines in the final days of the war to get to Kabul’s CIA-controlled Eagle Base. From there, he was airlifted to the Hamid Karzai International Airport, where he briefly worked security before being handed $8,000 in cash — half a year’s salary — and flown with his wife and three young children to Fort Dix.

At 37, with a seventh-grade education, Hayanuddin, along with his comrades, is facing a reversal of fortune that is humiliating, infuriating, and utterly intractable. After almost two decades as an American proxy — from guarding U.S. bases to killing Afghans in partnership with the world’s most powerful intelligence agency — he has landed, as a poor and vulnerable refugee, in a three-bedroom apartment with flowered curtains he had to harangue the resettlement agency to install in keeping with Pashtun culture, which dictates that a woman must be shielded from the eyes of passing strangers.

The Zero Units, also known as Counterterrorism Pursuit Teams, were born soon after the first U.S. military and intelligence operatives arrived in Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Formed in 2002, they operated entirely under U.S. control until 2012, Gen. Yasin Zia, Afghanistan’s former chief of Army staff, told me in August from London, where he leads an anti-Taliban resistance force. “The government of Afghanistan had no interference in these units,” said Zia, who spent many years in senior roles in the U.S.-backed Afghan government, including as deputy director of the Afghan intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security, which nominally oversaw the units in recent years.

The first of what would become the Zero Units operated in eastern Afghanistan, in a mountainous area along the Pakistani border where the Taliban and other militants often sought refuge between attacks on U.S., NATO, and Afghan government forces. That militia, known as the Khost Protection Force, or KPF, covered the southeastern region of the country. Later, the CIA created and trained at least three more units: 01, which operated in Kabul, Logar, and Wardak provinces in central Afghanistan; 02, based in Jalalabad, which fought in the east; and Hayanuddin’s unit, 03, based in Kandahar and fighting across the south.

In 2010, under pressure from then-Afghan President Hamid Karzai, U.S. officials agreed to transfer oversight of the Zero Units to NDS “physically, but not technically,” Zia said. “We had the names and ranks of members of Zero Units,” he told me. “But their salary was paid by Americans, their targets were given by Americans, and until the end the Americans were with these units.”

“Their salary was paid by Americans, their targets were given by Americans, and until the end the Americans were with these units.”

As the Obama administration transitioned from combat operations to a counterterrorism and advisory mission in Afghanistan after 2011, the U.S. handed control of several Zero Units over to the Karzai government, Zia said. But the CIA retained control of other key units, including the Kabul-based 01; the KPF; and Hayanuddin’s 03.

The units targeted the Taliban, the Haqqani Network, and Al Qaeda, but they were not accountable to the Afghan government — not even to the president. In 2019, Afghanistan’s then-national security adviser, Hamdullah Mohib, responded to allegations of extrajudicial killings by 01 — including massacres of children in madrassas — by noting that the unit operated “in partnership with the CIA.”

Hayanuddin had a front-row seat to the shambolic American withdrawal from Afghanistan, and now he can describe what he saw and heard in the war’s final months. The Zero Units were built to work in tandem with U.S. air support, but in August 2020, a year before the government of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani collapsed, U.S. forces began to radically scale back their air support for his unit, Hayanuddin said.

“Our American advisers left our bases for Kabul, and the choppers that would wait in our base on the edge of Kandahar City left with them,” he recalled. “Our commanders would only report to Americans about our operations, and the Americans would just say, ‘Go ahead.’ We were not working as closely as we used to.”

When the Americans took away their planes, the Afghans’ missions grew much more treacherous. “The American surveillance aircraft would tell us how many people were inside a building and how many of them were armed, and what weapons they have,” Hayanuddin said. “But those details were not there anymore.”

With U.S. air support gone and the fledgling Afghan Air Force unable to provide comparable intelligence, more Zero Unit members got hurt. The planes that had once ferried them to field hospitals in minutes were gone too. In February 2020, when U.S. drones and other aircraft circled over their operations, one of Hayanuddin’s comrades, Akmal, was blown up by a roadside bomb. The Americans airlifted him to a military hospital and he survived, Hayanuddin said, though he lost both his legs. But eight months later, another unit member, Shahidullah, was shot twice in the abdomen. This time, there was no airlift, and Hayanuddin’s unit was stuck in enemy territory. Shahidullah died on the spot.

After President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, the CIA gave the NDS a year’s budget for the Zero Units and said the agency would no longer support them, Zia told The Intercept from London. But the final Zero Units were not transferred to Afghan control, he said, until after Biden announced the full U.S. withdrawal in April 2021 and the last American forces and intelligence operatives began to leave.

Members of the Taliban give a tour of the destroyed CIA-operated Eagle Base in Deh Sabz district, northeast of Kabul, on Sept. 6, 2021.

Photo: Aamir Qureshi/AFP via Getty Images

“Like Committing Suicide”

The Zero Units were designed to capture and kill in targeted raids, not to fight on battlefields. They were widely known as among the most effective elite units in the Afghan security forces, and last summer, as the U.S. military pulled out and the Taliban advanced, many in the Ghani government and the Afghan military looked to them for salvation.

“I am not sure if our commanders got some money in bribes from provincial officials or the government in Kabul,” Hayanuddin said. “But they started turning a blind eye to our standards and sending us to several missions a day and making us suffer heavy casualties.”

Sometimes seven or eight unit members were killed each month, he said, an unprecedented rate for the elite unit. “Once, I remember that all our unit members started crying and protesting because of being overused. Our commanders never listened to that. They would still force us to go to operations all over the south.”

As casualties rose and the war intensified, the morale of Zero Unit members cratered, an Afghan doctor who fought for 02 told me. Like Hayanuddin, the doctor was evacuated last summer; he asked me not to use his name for fear of repercussions now that he and his family are in the United States.

When his commander would ask militia members to go on operations, the doctor told me, some would faint. They would say that “going to an operation is like committing suicide,” he recalled, “as there is no air support and not enough weapons and equipment.”

Rumors that U.S.-Taliban peace talks in Qatar had yielded an agreement to essentially give Afghanistan to the Taliban didn’t help. “The Taliban would send tribal elders to different security forces and tell them that it was decided in Doha that the province where they are stationed should be handed over to the Taliban, so better you don’t fight and avoid the casualties,” the doctor said. “The security forces would accept that and give up fighting.”

The Afghan security forces couldn’t keep up with the losses. In May 2021 alone, more than 400 pro-government forces were killed. Afghans were no longer willing to join the security forces because the job had become too dangerous.

“We had very smart people in our unit,” Hayanuddin said. “I remember that on a single day, one of our guys, without proper equipment, cleared nearly 30 roadside bombs” in Maiwand District, a Taliban stronghold west of Kandahar. Fighters with 03 repeatedly forced the Taliban out of Kandahar’s Arghandab District in the spring of 2021, he said, but when the regular Afghan army and police took over, the Taliban surged back.

Both Hayanuddin and the doctor from 02 suspect that the Afghan security forces largely surrendered the south not because they were defeated on the battlefield but as part of a political deal. They were not alone in thinking this. In the summer of 2021, the Taliban took control of dozens of Afghan police outposts in the districts surrounding Kandahar.

“It was a political deal which led to a wave of collapse of hundreds of outposts first in the south of the country.”

“The leadership of the Afghan security forces asked ground forces in many provinces across the country to stop fighting. We have seen videos on social media that soldiers were crying when they were told to leave their outposts and drop their weapons,” Mirza Mohammad Yarmand, a former Afghan deputy interior minister and military analyst, told me. “This means that it was a political deal which led to a wave of collapse of hundreds of outposts first in the south of the country.”

Soldiers who insisted on fighting found their supply lines cut and didn’t get the support they needed, Yarmand said, adding that when Afghan forces in the northern province of Takhar wanted to stand their ground, they were given a choice: surrender to the Taliban or drive to the mountains of Panjshir, where the last forces resisting the Taliban were holed up.

Near Kandahar, Hayanuddin’s unit ran into police officers trying to flee. “They said their outpost was captured by the Taliban,” he recalled. “We took them with us, and there was no Taliban in their outpost. When we asked why, they said their tribal elder told them to leave the outpost to the Taliban. This is only one example, but it happened many times.”

In June 2021, 03 was deployed from one front line to another as district after district fell to the insurgents. By the end of that month, nearly half of Afghanistan’s districts were under Taliban control.

As the fighting intensified, other Afghan security forces pinned their hopes on the Zero Units. On August 4, 2021, I was with the Afghan National Police Counter Resistance Unit outside Sarposa Prison, one of the main front lines in Kandahar. The fighting picked up on one edge of the city just as the police machine gun stopped working. I asked Shafiqullah Kaliwal, a unit commander, what they were going to do.

“The 03 will come,” he told me, “and they will push back the Taliban to their original outposts.”

The next day, Kaliwal told me that 03 had indeed come to their rescue and forced the Taliban to retreat. But when the Zero Unit moved on, the Taliban quickly recaptured the territory.

Zia confirmed that the pressure on Zero Units was unsustainable. In the last four months of the war in Kandahar, Zia said, “the casualties of Zero Units were very high. It was not comparable to the past 20 years of war. The reason for that was that they were not used professionally.”

A Taliban flag flies at a square in the city of Ghazni, Afghanistan, after the Taliban captured the provincial capital, on Aug. 12, 2021.

Photo: Gulabuddin Amiri/AP

A Secret Deal

One of the many mysteries of the war’s final days was how the Zero Units managed to make their way through Taliban-held territory to Kabul, where they were evacuated to the United States and other countries. An apparent agreement between the Taliban and the U.S. helps explain their unlikely escape.

On August 11, 2021, one of the main government lines of defense in Kandahar City collapsed to the Taliban. Hayanuddin was on leave at the time, but the next day, he said, his comrades in 03 and other security forces drove to Kandahar Air Field, which by then was in Taliban territory. There, they spent two days waiting to be flown to Kabul.

On August 14, the Taliban captured Jalalabad City, the provincial capital of Nangarhar Province, where Hayanuddin was spending his leave with his family. Terrified, he and his younger brother, who had also served in 03, stayed up all night, trying to contact Hayanuddin’s commander for orders. When they finally reached the commander, he told them to get to Kabul. The next morning, they climbed into a taxi and set off on an anxious two-hour journey through territory now controlled by their enemies. If anyone identified them, they thought, they would be killed.

But the trip was far easier than they’d expected as, one after another, the Taliban fighters manning checkpoints let them pass. “We didn’t know what was happening,” Hayanuddin told me. “They were our enemy. We were intensively fighting just a day before the collapse, but now we were staying in their territory or driving through it. We thought we were taking a big risk, but now as I think about it, it seems the Taliban didn’t want to attack us as part of their deal with the U.S.”

It wasn’t just a few guys in taxis who managed to cross Taliban checkpoints with ease. On August 15, the day Kabul fell to the Taliban, the doctor from 02 told me that he drove from Jalalabad to Kabul with his fellow unit members in a convoy of hundreds of military vehicles packed with weapons and equipment. The doctor thought they would have to fight their way through the checkpoints, but each time, the Taliban soldiers called their commanders and waved him and the other Afghan militiamen through.

The Taliban allowed Zero Unit members to safely cross their front lines in the final days of the war because they had agreed with the U.S. government to do so.

The Taliban allowed Zero Unit members to safely cross their front lines in the final days of the war because they had agreed with the U.S. government to do so, according to the doctor from 02 and two former Afghan intelligence officials, who asked not to be named because they feared repercussions from the Taliban for speaking to a journalist. The U.S. evacuation plan depended on Zero Unit members working security at the Kabul airport, and the Americans had told those fighters to get passports shortly before the republic collapsed, Zia, the former senior security official, said.

The CIA declined to comment. The Taliban did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Hayanuddin and his brother made it safely to Eagle Base, the Kabul headquarters of the CIA and 01, where they spent three nights. One by one, the Zero Units boarded Chinook helicopters and left the base for the Kabul airport: first 01, then 02, and then Hayanuddin’s unit, 03.

Hayanuddin spent five nights in the airport, providing security for the evacuation of thousands of desperate Afghans. In those days and later, Zero Unit members were accused of firing over the heads of crowds and beating Afghan civilians who were trying to leave. Hayanuddin denied mistreating people at the airport, but my own encounter with a Zero Unit fighter on August 19 suggests there is truth to the charges. As I made my way through crowds in front of the airport terminal, trying to reach my American colleague and the U.S. Marines, a member of the Zero Units stopped me. I explained who I was and where I was going, but the fighter ordered me to sit down. If I didn’t, he said, he would shoot me with dozens of bullets, and no one would question him.

At last, it was Hayanuddin’s turn to call his family to join him on a flight to the U.S., via Abu Dhabi and Germany. Like many Afghans, Hayanuddin was married to two women. He had moved one of his wives, who he asked me not to name, to Nangarhar with their three kids several months before the collapse, and one of his brothers managed to escort them to Kabul to meet Hayanuddin at the airport. But Hayanuddin’s other wife was still in his home province of Kunar with their four children when the republic fell.

“My first wife, who was in Kunar, couldn’t make it to Kabul,” he told me, “because there was no one to accompany her.”

Hayanuddin also left his parents and siblings behind, including the brother who had served alongside him in 03. The Americans refused to evacuate him, Hayanuddin said, because he had left the unit a year before the Taliban took control.

Thankful, but Angry

In Pittsburgh, Hayanuddin and several other Zero Unit members found work at a halal grocery. One of them was Khan Wali Momand, a former school principal who started working for 02 in Jalalabad as a security guard in 2017. Momand now lives with his wife and children in Section 8 housing in Duquesne, a Pittsburgh suburb. When I met him, he was unloading boxes; he has since gotten a different job at another local grocery store, which he prefers because it doesn’t involve as much heavy lifting.

Momand started working with 02 through his brother, Inayatullah, who he says served 16 years with the unit but left just days before the government collapsed because his wife was ill. Like Hayanuddin’s brother, Inayatullah was left behind when the Taliban took over, and he and Momand’s other relatives immediately became targets for retribution. Inayatullah went into hiding, and when I spoke to Momand this spring, he was consumed by grief and worry. “Every time I receive a call from home,” Momand told me, “I think it will be bad news.”

This spring, members of the Taliban kidnapped two of Momand’s teenage nephews and held them for five days in an attempt to force the family to hand over Inayatullah. The nephews were released after tribal elders in the area promised to help the Taliban find Inayatullah. He has applied for a Special Immigrant Visa to come to the United States, Momand said, but has not heard back.

“We were so loyal to Americans that we wouldn’t leave their bags behind in the battlefield, but now they are leaving behind my brother, who helped them for 16 years,” Momand told me. “It happened many times during missions with 02 that an American adviser or soldier would get shot, and we would risk our life to take them out of the battlefield. Look at our level of loyalty and their level of loyalty.”

Momand is deeply conflicted over his role in the war. When he began working with the Americans five years ago, he drew the enmity of the Taliban and many acquaintances. In his conservative village, he had a hard time defending his decision and explaining how helping the Americans would benefit his country. Now he wonders whether he made the right choice — whether it was worth it, given the price he and his family have paid. He’s an outsider in Duquesne and may never be able to go back to Afghanistan. Did he join 02 for the wrong reasons, he wonders, or was he used? Did he betray his country, his people, after all?

Momand said he is grateful to Biden. “He hasn’t left us to the Taliban. If I had been left behind in Afghanistan, my whole family and I would have been killed by now,” he said. “But there is no one in the U.S. to rescue me from the tough situation here.”

As our conversation drew to a close, Momand’s anger flared. He had told his story many times, he said, to workers from resettlement agencies and other relief organizations. “Everyone comes here and asks about my problems and the problems of my family, but I don’t see any outcome of telling these stories,” he said. “Do you enjoy hearing my painful life story?”

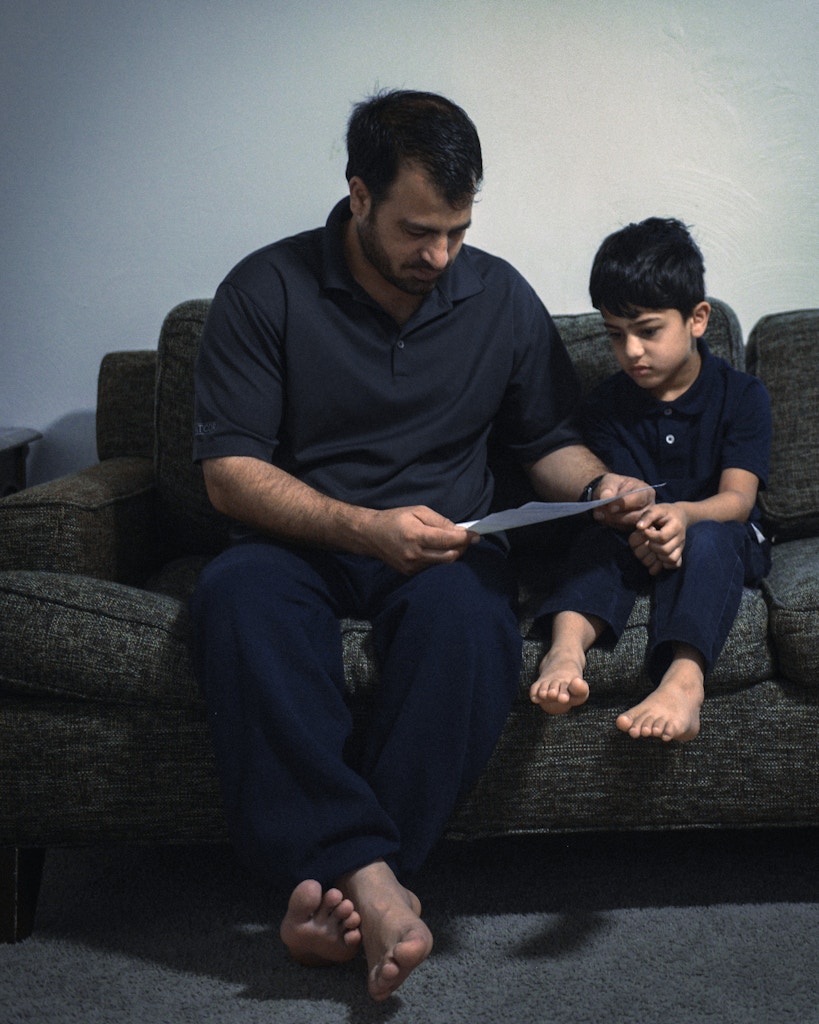

Hayanuddin reviews a document he received through the U.S. Postal Service, a new concept for him, as his son looks on in their home in Pittsburgh.

Photo: Fahim Abed for The Intercept

Only in the Darkness

At Hayanuddin’s house that rainy May morning, an oilcloth was spread over the living room carpet, and we sat around it while his wife and 9-year-old daughter, Simina, brought out loaves of hot fresh bread, eggs, warm yogurt, and a giant thermos of sweet, milky black tea.

As we ate, Hayanuddin kept an eye on his phone. At 9 a.m., an alarm sounded, and Simina brought him a pair of white athletic socks, a jacket, and an umbrella. Back in Afghanistan, his American advisers had stressed the need for punctuality, often arriving 15 minutes early for meetings with their Afghan counterparts. He feared that if he were late to work, he’d get fired. And he needed this job.

He took home about $1,600 a month after taxes, he told me. The resettlement agency was covering the first three months of rent on his apartment in Pittsburgh; after that, he’d have to spend $1,500 a month, nearly his entire paycheck, on rent and utilities. He was getting food stamps, but the family budget was tight.

His house was about five miles from the halal grocery, an easy 15-minute drive. But the bus ride, including a transfer downtown, could take more than an hour. On this day, he would work for nine hours, arriving home between 9 and 10 p.m. The family, including the children, would eat a late dinner together. After that, they’d call Afghanistan, so Hayanuddin and his wife could talk to their parents, and the parents could speak to their grandchildren.

It was his father, Hayanuddin says, who had convinced him to go to the U.S. last year. “If the Taliban come and they behead you in front of us or shoot you in the head in front of us, that would be a very big trauma for us for our whole life,” his father told him last August. “So if you want to spare us that pain, you should leave.”

He sometimes regrets it. “We didn’t voluntarily come here, and it is not easy here,” he told me. “That’s the everyday struggle. And then you have a family that is staring at you and hoping that you will fix everything.”

At 9:20 a.m., Hayanuddin pulled on a black jacket and headed out to the bus stop, a wooden pole with a metal sign at the edge of a busy road. He hunched his shoulders against the rain and took a drag on his Marlboro Red. The resettlement agency gave him transit cards, but when they ran out, he’d have to spend his own money on bus fare.

Back in Afghanistan, he drove heavy military vehicles over mountainous terrain wearing night vision goggles. But in Pittsburgh, he couldn’t get a driver’s license. The test was offered in Urdu and Arabic, but not Persian or Pashto, Afghanistan’s two main languages, and at the time, translators were not allowed. (Several months later, after the local Afghan community complained, the DMV added a test in Persian.)

“If I would stand in a bus stop in Afghanistan, I would just wave to a taxi and they would stop and take me to where I wanted to go,” he said. “There is no country as good as Afghanistan around the world, if only it were safe enough to live in.”

After 15 minutes, the bus arrived. Hayanuddin, thoroughly soaked, donned a surgical mask, climbed the steps, and settled into an empty seat. As the bus heaved along the twisting roads, heading downtown, he surveyed the other passengers.

“Only poor people like me are using the bus,” he noted.

Back at his apartment, he’d shown me a stack of military ID cards and commendations from the Americans he’d worked with, each signed by a different soldier or officer, praising his service and making promises they couldn’t keep.

“Your exemplary actions demonstrate your overall commitment to not only safeguard your Village, your District, and Province from those who inflict harm upon the innocent, but also to ensure a better future for all current and future Afghan citizens,” read one certificate, signed by “Master Sergeant Scott” and “Commander Josh” of Special Forces unit ODA 3115.

“His expertise, unfaltering dedication to duty and work ethic have far exceeded my expectations and he is an inspiration for all who work with him,” said another, marked QSF — for Qandahar Strike Force — National Security Unit 03 and dated March 2021. “Over the past 6 years, He has demonstrated his total loyalty to his unit. His service to the country is a shining example for all his fellows’ unit around him and he demonstrates an unfailing commitment to a free and prosperous Afghanistan.” It was signed by “Mac,” a U.S. adviser.

“Mr. Ayanudin will be a great asset to the SRF-03,” read a commendation from 2015, “and will make a significant contribution to a free and prosperous Afghanistan.”

What to make, now, of those papers, those words?

More than an hour after leaving his house, Hayanuddin disembarked on a desolate street corner and walked a block to the halal grocery, a sprawling brick warehouse complex with murals paraphrasing Martin Luther King Jr.: “Only in the darkness can you see the stars.”

Inside, he traded his jacket for a white apron and reappeared behind the meat counter, where he used a mechanized blade to slice chicken breasts.

WAIT! BEFORE YOU GO on about your day, ask yourself: How likely is it that the story you just read would have been produced by a different news outlet if The Intercept hadn’t done it? Consider what the world of media would look like without The Intercept. Who would hold party elites accountable to the values they proclaim to have? How many covert wars, miscarriages of justice, and dystopian technologies would remain hidden if our reporters weren’t on the beat? The kind of reporting we do is essential to democracy, but it is not easy, cheap, or profitable. The Intercept is an independent nonprofit news outlet. We don’t have ads, so we depend on our members — 35,000 and counting — to help us hold the powerful to account. Joining is simple and doesn’t need to cost a lot: You can become a sustaining member for as little as $3 or $5 a month. That’s all it takes to support the journalism you rely on.

No comments:

Post a Comment