Sudha Ramachandran

Sixty years ago, on November 21, China declared a unilateral ceasefire against India bringing to an end the month-long India-China border war. Of the territory it occupied in the war, China retained control of Aksai Chin in the western sector of the disputed border but, although it took control of almost all of the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) or today’s Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern sector, it withdrew 20 kilometers north of the McMahon Line. The pullback of Chinese forces north of the McMahon Line suggested that China was perhaps not serious about pressing its claims in the eastern sector. However, since the mid-1980s, it has robustly asserted claims over some 90,000 square kilometers of territory in India’s northeast, which roughly approximates the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh or what China calls Southern Tibet.

In a conversation with The Diplomat’s South Asia Editor Sudha Ramachandran, author, historian and Tibetologist Claude Arpi points out that China “has not always claimed” NEFA/Arunachal and that its assertion of claims here is to gain leverage over India in a future border settlement.

When the war ended on November 21, 1962, China retained control of Aksai Chin but pulled back from India’s Northeast. Why?

The two sectors are historically very different.

To understand, it is necessary to go back to the Bandung Conference in 1955. An apparently moderate Zhou Enlai [China’s premier] convinced [Indian Prime Minister] Nehru of the “sincerity” of the Chinese Communist rulers. Writing about his encounter with Zhou at the Conference, Nehru said: “When asked if he wanted to push communism into Tibet, Chou En-lai [Zhou Enlai] laughed and said that there could be no such question as Tibet was very far indeed from communism. It would be thoroughly impracticable to try to establish a communist regime in Tibet and the Chinese Government had no such wish.”

A few days later, the Indian prime minister told the Indian foreign secretary about a remark by the Chinese premier on the McMahon Line: “Although [Zhou] thought that this line, established by British imperialists, was not fair, nevertheless, because it was an accomplished fact and because of the friendly relations which existed between China and the countries concerned, namely, India and Burma, the Chinese Government were of the opinion that they should give recognition to this McMahon Line.”

Five years later, Zhou Enlai visited Delhi and had long talks with Nehru. In an informal encounter with Indian Defense Minister V.K. Krishna Menon, Zhou explained that in the Western Sector (Aksai Chin) there had never been any delimitation and only an old treaty (of 1842), which did not mention any area; Aksai Chin, he affirmed, had always been part of Sinkiang (today’s Xinjiang) and the [Aksai Chin] road built by China (without India realizing it) was on Chinese territory.

Later, Zhou tested the ground for a “swap”: India would acknowledge Aksai Chin as Chinese and Beijing would recognize the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA or today’s Arunachal Pradesh) as Indian.

One has to understand that for Beijing Aksai Chin was strategically far more important than the NEFA. The road built in the early 1950s linked the two newly-acquired provinces of the People’s Republic of China, Xinjiang and Tibet.

Therefore, for Mao and his colleagues, there was never a question to return Aksai Chin to India. Further, Beijing has argued that the Communists started surveying the Aksai Chin road in 1952, the construction began in 1954/55 and it was inaugurated in 1957; during all these years India did not complain. Delhi only started objecting to Beijing in 1958. For the Chinese leadership, it was proof that the area never belonged to India.

On the opposite end, NEFA saw very few incursions from the Chinese troops south of the McMahon Line (the first one took place in Longju in August 1959). An early incursion had happened in the Walong sector in 1910, but the Chinese troops quickly returned to their barracks north of the watershed.

All this shows that both areas do not have the same strategic importance for the Chinese.

It is probably why China decided to withdraw from the NEFA in 1962.

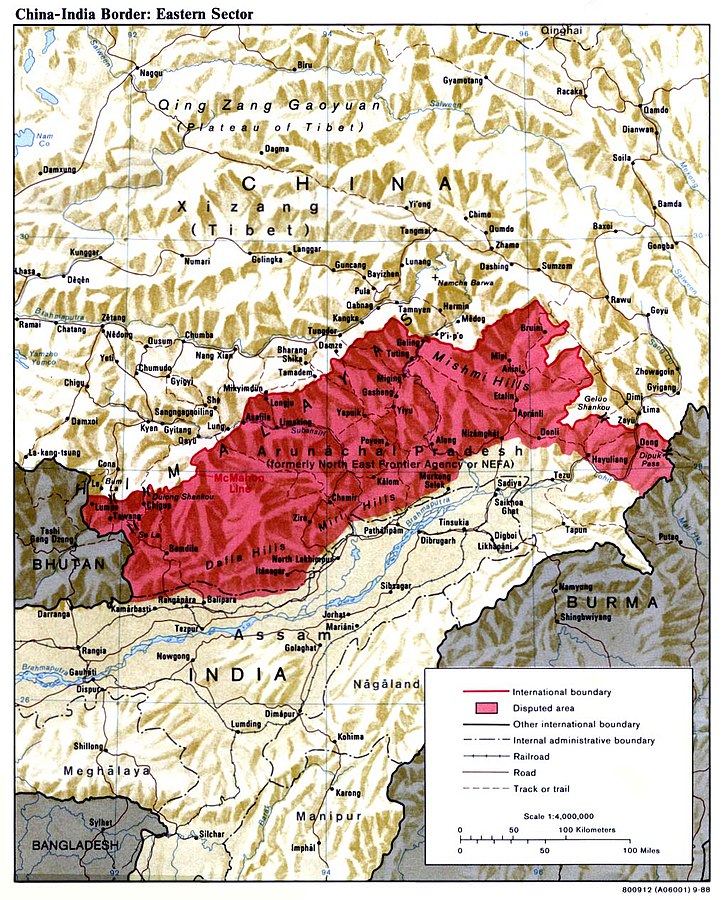

The eastern sector of the India-China border, depicting the disputed area of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which China claims as Southern Tibet. Map by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

Since the mid-1980s, China has been reasserting rights over Arunachal Pradesh. Why the renewed interest in this territory?

During the last few months, Beijing’s propaganda has reiterated that the entire Arunachal Pradesh is part of “Southern Tibet.”

On November 10, Xinhua published a news item: “A 5.6-magnitude earthquake jolted Medog County in Nyingchi City, southwest China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, at 1:01 pm, Beijing Time, according to the China Earthquake Networks Center (CENC). The epicenter was monitored at 28.35 degrees north latitude and 94.48 degrees east longitude, with a depth of 10 km, the CENC said.”

The area mentioned is near Likabali in Arunachal Pradesh.

In January 2022, Global Times announced new names of 15 places in Arunachal Pradesh, given with precise coordinates. Eight were residential areas, four were mountains, two were rivers, and one was a mountain pass (Sela). It was the second batch of so-called standardized names of places published by the Chinese government; the first batch of the so-called standardized names of six places in Arunachal was released in 2017. This is part of the propaganda to assert China’s claims.

For Beijing, it is a bargaining chip for an eventual “swap” and the recognition by India of the occupation by China of Aksai Chin.

It is interesting to look into the rationale of the Chinese claim over NEFA/Arunachal. The origin is linked to the creation of the Xikang province. In the 1930s, a Chinese scholar, Ren Naiqiang was encouraged by Liu Wenhui, the governor of Xikang, to produce a map of the area. Though the Chinese had never set foot in the area, the new map included NEFA in the new Chinese province.

In 1939, the Nationalist Government formally established a new province called Xikang (more or less corresponding to Tibet’s Kham province).

At the end of 1949, Ren Naiqiang met Marshal He Long, one of the senior-most generals of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and explained why his map was dependable; the Marshal was convinced and ordered the distribution of copies. On January 10, 1950, He Long sent a report to Mao Zedong strongly recommending that Ren’s map should be accepted and circulated amongst the PLA. It is after this episode that Beijing started claiming NEFA as Chinese. This shows that China has not always claimed NEFA.

Why is Tawang important to China?

China has never officially accepted the existence of the Tibetan exile government. If India would return Tawang to China (including the monastery), it would be a denial by Delhi that the 1914 Indo-Tibet border agreement and the McMahon Line ever existed.

The fact remains that the border agreement of March 1914 had been signed with official seals by the Foreign Secretary of India (Sir Henry McMahon) and the Prime Minister of Tibet (Lochen Shatra).

It is also true that monastic taxes in the area were being collected by Tibetan officials till February 1951, when the expedition led by Maj. Bob Khathing took over the Tawang administration.

But taxes paid by a monastery do not amount to ownership certificates. Several monasteries in the Indian Himalaya have been affiliated with large monasteries in Tibet; it does not mean that these monasteries belong to China.

Another factor is that the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, was born in Urgyeling, south of Tawang. It is another pretext for China to claim the area. But the fact that a religious leader is born on a foreign territory is not legally considered a valid argument to claim ownership of the country (or the area where the leader is born).

Not often mentioned are the bitter relations existing between the Monpas and the Tibetans till the arrival of Major Khathing. In 1938, when Captain Lightfoot, the Assistant Political Officer (APO) in Balipara (Assam) visited Tawang, he noted: “Our visit raised hopes that they might be relieved of the Tibetan yoke but there was grave uneasiness at our departure lest they should be punished for the help they had given us… Tibetan domination is loathed by the Monpaas and is intolerable by any civilized standards.”

The APO observed that forced labor and extortion of supplies, failure by the Tibetans to protect the Monpas, payment of tribute at rates bearing no relation to the ability of villagers to pay, and finally a brutal and unspeakably corrupt judicial system made the local Monpas believe that they were “liberated” by Major Khathing and his Assam Rifles from the Tibetan yoke in 1951.

India has improved connectivity and military infrastructure along the LAC in the eastern sector. How does it match up to infrastructure on the Chinese side?

Because of the nature of the terrain, India will never match China in terms of infrastructure, but since a few years, the mindset of the government has changed and serious efforts have been made, if not to at least “catch up” to have a decent infrastructure to the border districts/circles in India.

To give a few examples, Hollongi Greenfield Airport, also called Donyi Polo Airport, near Itanagar, serving Arunachal’s capital has recently been opened.

On November 2, a Dornier D-28 aircraft landed at the Ziro Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) in the Lower Subansiri district; commercial operations are expected to start soon. The 17-seater aircraft was operated by Alliance Air. ATR-72 and Dornier D-228 are already operational at Pasighat (Assam) and Tezu airports.

Arunachal Pradesh now has four airports (Itanagar, Ziro, Pasighat, and Tezu) and nine ALGs at Aalo, Mechuka, Pasighat, Tawang Air Force Station, Tuting, Vijaynagar, Walong, Ziro, and Daporijo. Several helipads have also been built near the McMahon Line.

While most of the existing roads have been improved, for example between Tezpur in Assam and Tawang, many new ones closer to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) have been built. Further, the traffic on the Bomdila-Tawang road will greatly improve with the opening of the tunnel under the Sela pass at the end of the year.

Even the last post in the Upper Subansiri district (in Maja), will soon be connected.

But first and foremost, what has changed is the mindset. A few years ago, one often heard: “We don’t need good roads, if the Chinese come again, they will break their vehicles on our poorly-maintained tracks.”

Today, the Arunachal Pradesh government as well as the Indian Army understand the necessity of dual-use infrastructure, not only for defending the border, but also helping the remote villages to survive.

Could you throw light on India’s “Vibrant Villages” scheme? What underlies the development of these villages?

To understand the “Vibrant Villages” scheme one has to look at the other side of the McMahon Line.

The Sixth Tibet Work Forum (TWF), held in Beijing on August 24 and 25, 2015 was a turning point for the Tibetan plateau. Tibet Work Forums are large meetings called every 5 to 10 years to discuss the Chinese Communist Party’s Tibet policies. They are attended by all the members of the powerful Politburo Standing Committee, members of the Central Committee, or senior PLA generals. The Sixth Forum decided to tackle poverty and develop Xiaokang (“moderately well-off”) villages on the plateau.

In 2017, soon after the conclusion of the 19th Congress, President Xi Jinping wrote a letter to two young Tibetan herders who had written to him introducing their village, Yume, north of the Upper Subansiri district. Xi “encouraged a herding family in Lhuntse County …to set down roots in the border area, safeguard the Chinese territory and develop their hometown.” Soon after, Yume became a model village for more than 600 Xiaokang villages, a large number located close to the Indian border.

The “Vibrant Villages” is a response to hundreds of Xiaokang villages, which have mushroomed on the Tibetan plateau. In India, they are also meant to tackle another genuine problem: large-scale migration from the border areas.

According to the Central Government’s announcement, India plans to open the villages along the Chinese border for tourists.: “The activities will include construction of village infrastructure, housing, tourist centers, road connectivity, provisioning of decentralized renewable energy, direct-to-home access for Doordarshan and educational channels, and support for livelihood generation.”

The government’s objectives are clear: “to enhance infrastructure in villages along India’s border with China, in states like Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Arunachal Pradesh.”

Like in Tibet, the scheme is based on the premise that the border areas will be opened to tourists, which will provide the economic backbone for the scheme. Several measures to remove/relax the Inner Line Permit system and other restrictions have already been taken, in Ladakh in particular.

If successful, it should give a boost to the local economy and benefit the populations living in these remote, largely inaccessible border areas. It will also enhance the defense preparedness of the Indian defense forces, which can use the newly created infrastructure.

No comments:

Post a Comment