Lieutenant (junior grade) Jeong Soo Kim

You are a proud Russian air assault force (VDV) paratrooper. You are fit, motivated, and proficient in shooting, moving, and communicating with your personal and crew-served weapons. Your unit recently practiced combined-arms warfare in Belarus and now is deployed to a “special military operation” in Ukraine.

Your platoon is accompanying tanks to clear a town of resistance. You spot a drone trailing your platoon and suspect it is hostile. You report this situation to your company command post and request antiaircraft missiles to destroy the drone. The request is approved, but since the antiaircraft battery reports directly to the battalion tactical group, it will take a few hours for them to arrive. Frustrated, you attempt to shoot down the drone with organic weapons. You are not successful because you received no training on aerial gunnery. A few minutes later, a barrage of mortar shells and Javelin missiles decimate your platoon, and you are now dying on the outskirts of Kiev.1

Marines prepare to fire an FGM-148 Javelin during a February 2021 exercise. To fully transition to fourth-generation combat, the Marine Corps must work to bring down the prices of man-portable missiles and drones so they can be used in exercises and bought in quantities necessary to dominate on tomorrow’s battlefield. U.S. Marine Corps (Hassanen Attabi)

Opposing this Russian platoon is a Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces (TDF) squad. They are teachers and factory workers who occasionally drilled while balancing careers and family obligations. They are older, physically weaker, and not as proficient with their weapons, nor can they conduct large combined-arms operations. However, they are not constrained by traditional doctrine like the VDV, which practiced legacy combined-arms tactics. Instead, the TDF use commercial drones combined with mortars and missiles to create a tight kill chain that out-decided and destroyed a heavier, more “powerful” foe.2

While Ukrainian success on the battlefield is worthy of celebration, it is not difficult to observe that the U.S. Marine Corps more closely resembles the Russian VDV than the Ukrainian TDF in its current organization, equipment, and tactics. The Marine Corps infantry’s reliance on automatic fire, indirect weapons, and radios to conduct combined-arms warfare constitutes a refined version of a legacy generation of warfare. While Force Design 2030 (FD 2030) introduces much needed modernization to the infantry, it does not do enough to take the infantry into the next generation.3 To dominate the 21st-century battlefield, Marine Corps infantry must integrate drones at every level, field affordable loitering munitions, and equip every unit to counter small aerial targets, such as drones and loitering munitions.

What are Generations in Warfare?

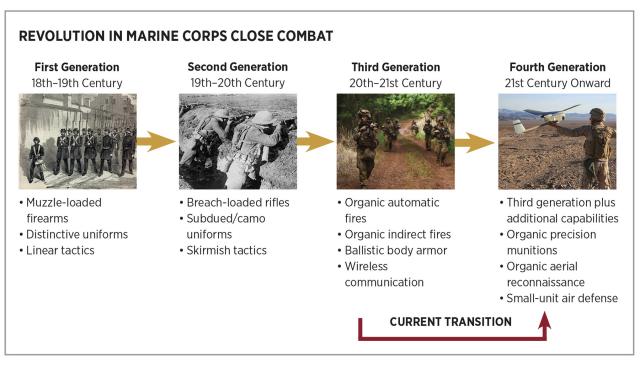

Combat will always be brutal and consequential, but technological advances allow forces to undergo revolutionary improvement in combat effectiveness. While equipment and training are constantly refined, the Marine Corps has undergone three broad, generational revolutions in combat effectiveness in its history. The figure below illustrates these three generations and what the emerging fourth generation may look like.

The first generation encompasses the bright uniforms, linear tactics, martial music, and muzzle-loaded firearms typically associated with the 18th and early 19th centuries. The limited range of firearms made combat especially close and brutal, and required unwavering discipline demonstrated by a unit’s ability to maintain linear formation even under fire.4

As industrialization enabled mass production of breach-loaded rifles and smokeless ammunition, the Marine Corps transitioned into the second generation of warfare. Units wore subdued uniforms and adopted skirmishing tactics, cover, and concealment.5 These units dominated the battlefield from the mid-to-late 19th century to World War I, when industrial warfare necessitated another combat revolution.

Twentieth-century advancements in recoil-operated weapons, indirect fires, and wireless communication introduced third-generation warfare. In this generation, units organically deploy direct and indirect firepower previously available only to higher echelons. In addition to their increased organic lethality, third-generation forces use wireless communication to orchestrate combined-arms operations that encompass artillery, armor, engineers, logistics, aircraft, and even naval forces. The epitome of this generation is the Marine air ground task force (MAGTF).6

Currently, the Marine Corps conducts a refined version of third-generation warfare. However, the proliferation of drones and precision weapons, along with the Ukrainian forces’ success against the powerful third-generation Russian combat force are reminders that the Marine Corps cannot stop progress toward a new generation. The jury is still out on the details of what a fourth-generation force will look like, but evidence from experimentation with FD 2030 and lessons from the Ukrainian battlefield, indicate that such a force will focus on aerial surveillance drones, affordable precision munitions, and improved air defenses against small aerial threats. The service must sprint to this generational leap in combat capabilities or share the Russian battalion tactical group’s fate attempting to cross the Siversky Donets River.7

Current State of Modernization—and Gaps

Fortunately, FD 2030 has recognized all three critical components of a fourth-generation force. The Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, calls for drones to be deployed at the squad level and a specialized squad systems operator and assistant squad leader to be assigned to every infantry squad. Organic loitering munitions are being deployed at the infantry battalion level, giving tactical leaders organic capacity to conduct precision strikes. Littoral antiair battalions (LAABs) are being stood up to support the newly formed Marine littoral regiments (MLRs).8 While these initiatives are necessary, the Marine Corps must execute even more aggressive force modernizations and drive these three capabilities down to the squad level.

Marines conduct reconnaissance with an R-80D SkyRaider drone during a combat readiness evaluation. Organic surveillance capabilities such as these drones must reside in every squad in preparation for the next generation of combat. U.S. Marine Corps (Sarah Pysher)

Drones: Almost There

One of the immediate changes brought to the infantry squad was the addition of the squad systems operator (SSO).9 The SSO operates communications as well as systems, including quadcopter drones, and gives the squad leader expanded situational awareness to make better decisions in combat. The Marine Corps needs to ensure all squads, even those outside the infantry, receive SSOs—including those in combat support roles, such as combat engineers, who work alongside the infantry.

Organic surveillance capabilities must reside in every platoon and company. Platoon commanders who move with their squads, for example, may be allotted light quadcopters. As company command posts typically are more established, they should be allotted larger quadcopters, or even vehicle-launched fixed-wing drones, to give a more elevated, persistent vantage point.

Loitering Munitions: Capable But Not Yet Affordable

The next capability the Marine Corps must focus on is affordable loitering munitions. Precision weapons such as the FGM-148 Javelin and the Switchblade 300 loitering munition are extremely effective, but their costs are constraining, ranging from the Switchblade’s $6,000 to the Javelin’s $78,000 price tags.10 The high cost prevents training commands such as the School of Infantry Marine Combat Training from teaching Marines to use these munitions in frequent live-fire exercises. The high costs even prevent Fleet Marine Forces units from frequently experimenting and expending these munitions on training and field exercises. To fully transition into a fourth-generation combat force, the Marine Corps must reduce the cost of these and other precision munitions, enabling live-fire exercises to be as common as exercises with crew-served weapons are today.

Fortunately, there is historical precedent and success in introducing automatic weapons to every Marine. The first recoil-operated machine gun (Maxim gun) entered service in 1886. Like precision munitions of today, automatic weapons initially were too expensive to field in large numbers, and their cost prohibited full implementation for tactical units. For example, in 1939, it would have cost $209 ($4,500 in 2022 dollars) to purchase an M1928 Thompson submachine gun. A focused effort by the Ordnance Bureau to incentivize cost savings and mass production reduced the cost of a Thompson submachine gun to $45 (around $740 in 2022 dollars), comparable to the legacy M1903 Springfield’s cost of $41. By the end of World War II, automatic weapons, such as the M3 “Grease gun” submachine gun, were developed with a primary focus on affordability, enabling the U.S. government to put automatic firepower in the hands of an individual soldier for only $22.11

As with automatic weapons, the Marine Corps must strive to break through cost barriers with precision munitions. First, the service can set an aggressive price target (for example, $500 per round) that would allow units to expend precision munitions more readily during training and in combat, but be high enough to be viable from the defense industrial perspective. The Marine Corps also should take inspiration from the development of the M3 submachine gun to analyze how to simplify the current loitering munition design and make it more accessible to even non-infantry units. Third, the service should develop “practice” loitering munitions that will allow units to use munitions multiple times before they reach the end-of-service life to reduce the “per use” cost.

Small-Unit Air Defense: The Weak Link

While Force Design 2030 prioritizes drones and precision munitions, it is worryingly silent on small-unit air defense. The May 2022 update of FD 2030 only points to a “future publication of a Functional Concept for MAGTF Air and Missile Defense” and the test of a “Medium Range Intercept Capability (MRIC).”12 Press releases from Program Manager, Ground Based Air Defense (PM-GBAD), highlight vehicular platforms equipped with Stinger missiles and electronic warfare suites, demonstrating a focus on countering large aerial targets.13

The repeated destruction of Russian forces by Ukrainian drones should remind the Marine Corps that air defense focused on countering large aircraft is exposed on the contemporary battlefield to drones and loitering munitions. Deploying antiair units at no lower a level than battalion tactical groups, Russian units at the squad level had no effective active protection against air threats. Without such protection, most Russian units have had to rely on passive methods, such as cover and concealment, to counter detection. This weakness has been exploited by Ukrainian forces using inexpensive commercial drones to surveil, strike, and destroy Russian units.

While medium-range air-defense units are indispensable in countering low-flying tactical aircraft, they are mismatched for most aerial threats Marines will face on the future battlefield. Even the lightest platforms such as the Stinger weigh more than 30 pounds and cost orders of magnitude more than the small drones or loitering munitions that will be deployed by U.S. adversaries. Without an effective organic antiair capability, Marines in small fighting units not constantly supported by higher echelon air defenses will be relegated to passive methods such as cover, concealment, and decoys. Juxtaposed with constant improvements in computer vision that can discern targets from their surroundings, Marines will find it increasingly difficult to evade detection and targeting. The Marine Corps has yet to select systems or establish doctrine that will allow squads or platoons to destroy drones and loitering munitions.

Fortunately, the solution does not have to be heavy, complex, and vehicle mounted. Simple solutions, such as giving Marines additional training in shooting aerial targets with their individual weapons, could provide immediate stopgap antidrone capability. Computerized rifle sights specialized for counterdrone fire could increase the effectiveness of gunnery training. In the medium term, drone jammers could help Marines disable (soft kill) enemy drones without revealing their exact position and even intercept enemy intelligence by taking control of their drones.14 However, this small-unit focus does not mean larger defense assets are not effective. The Marine Corps lacks sufficient air defense at every level and should raise overall investment, not divest from any air defense.

Proposed ‘Fourth-Generation’ Squad

A Marine combat unit employing drone surveillance, precision munitions, and organic antiair capabilities will look and be organized differently than the modernized infantry envisioned in FD 2030. Most important, foundational units such as the squad should be capable of drone surveillance, precision, and antiair fires. To achieve this, each squad will have to consist of fire teams that specialize in different mission.

In this notional squad, the end strength would not change from FD 2030’s proposed 15 Marines. The roles of squad leader and assistant squad leader would remain similar, but the SSO would focus on aerial surveillance and battlefield awareness, while other fire teams operate loitering munitions and antiair weapons.15

The largest change from FD 2030’s design and this notional fourth-generational squad would be fire team specialization. The first fire team will act as the squad’s “long arms” and use loitering munitions and marksmanship to destroy the enemy at a distance. The second fire team will act as the “shield” and use computerized optics and drone jammers to provide the squad with both “hard” and “soft” antiair capabilities. The third fire team will be armed with conventional weapons to provide fire and maneuver in line with today’s doctrine. Despite the added technology, all will be deadly with their rifles and trained to the standard of “every Marine a rifleman.”

This notional squad would be a building block for platoons, companies, and battalions—adding robust capabilities and commanding and controlling other essential combat support and logistics units. If done right, a fourth-generation Marine Corps force will be a menacing presence on the battlefield, constantly aware of its surroundings and able to precisely strike the enemy’s weaknesses while defending itself against hostile loitering munitions and drones.

There is much work to be done as the Marine Corps modernizes Force Design 2030. Even though FD 2030 is extensive and transformative, the Marine Corps needs to do more to evolve the infantry squad into a fourth-generation force. The service must look ahead by analyzing the weaknesses of its units, and identify additional capabilities that need to be developed, implemented, and made more affordable. As the saying goes, “Change is the only constant in life.”

No comments:

Post a Comment