Tom Cooper

This morning, and amid an ‘entire string of counteroffensives’ run by the Ukrainian Armed Forces (ZSU) — I’ll, again, try to address just one of them, and then one about which there are many questions: the one in northern Kherson Oblast.

What happened there the last three days can be mostly deducted from Russian reports: so far, Ukrainians are rather reluctant to say what is going on.

Up front, it is obvious this operation was prepared in a much better fashion than the one from late August — even if its aims, probably even axes of advance, remained largely the same.

First problem was that during operations in northern Kherson in late August and early September, involved ZSU units quite quickly run out of artillery ammunition. The reason is that the ammunition expenditure in this war remains far higher than anybody expects. That said, the ammo was not spent for nothing: it severely depleted the opposition. Moreover, the ZSU offensives into eastern Kharkiv have forced the Russian Armed Forces (VSRF) to re-route lots of reinforcements and supplies in that direction: the concentration of VDV (Russian airborne units) and Separatist forces in Kherson Oblast — the two are commanded by the 49th Combined Arms Army (southern and western Kherson) and the XXII Army Corps (northern Kherson) - could not yet receive similar reinforcements.

The next problem was improving both electronic warfare (EW) support and reconnaissance. That the severe EW was deployed can be deducted from Russian reports about a break-down in communications and lack of air support. Almost certainly, this caused a break-down in the artillery support, too. Certainly enough, overpowering the under-equipped 205th Cossack Motor Rifle Brigade (Separatists) in the field of electronic warfare was easier than overpowering a crack VDV outfit, but still: this was so effectivelly cut off from the communications network that it found no way to call for help.

Reconnaissance was improved in so far that the ZSU took better care to find and neutralise Russian combat vehicles before launching its own attack. As a result, early reports indicated a loss of only one or two T-72Ms of the (‘destroyed’) 128th Mountain (compared to almost half a company during initial assaults of early August), in exchange for about half a battalion tactical group of the opposition (AFAIK, the total number of destroyed Russian vehicles reported by now includes about a dozen of tanks, a similar number of infantry fighting vehicles and armoured personnel carriers, and twice as many of other vehicles).

Another problem was that some of ZSU brigade commanders were still ‘leading from the front’: was ‘in’ — indeed: a sort of ‘status symbol’ — over much of the last 70 years, but is not ‘perfect’ for modern day warfare. Nowadays, COs are best serving if coordinating their troops from the safety of their HQs. They’ve got UAVs and the Kropyva automatic tactical management system, can monitor the battle ‘live’ and ‘from vantage point’, and see what’s going on much better than from the ground. Furthermore, I’m certain the ZSU deployed its special forces (apparently SSO Centre South Branch) behind enemy lines — in advance, and in order to provide additional info on enemy troop movements.

Finally, the opposition was of different ‘quality’: back in late August, the 128th Mountain was assaulting well-prepared positions of two BTGs of the crack VDV. As reported at the time, these suffered such losses that one had to be withdrawn from Kherson Oblast, completely. Thus, this time, the 128th Mountain was facing the (comparatively) poorly-armed 205th Cossack Motor Rifle Brigade (Separatists), and the depleted 83rd VDV Brigade.

Finally, this attack was to be supported by advances of the 35th Naval Infantry from the Inhulets Bridgehead, in northern (Davydiv Brid) and eastern direction (Bruskynske).

Action

On Sunday, 2 October, the Initial, multi-prong assault quickly collapsed positions of the 205th Cossack in Myroliubivka and Ljubymivka, causing its survivors to flee (reportedly: all the way to Beryslav, some 80km further south). This exposed the strongholds in Khreshchenivka and Zolota Balka: the 83rd VDV was meanwhile knocked out by a hit on its headquarters (causing at least the death of its deputy commander) and its survivors prompted into a quick withdrawal in direction of Dubchany.

The Russians ‘regrouped’ from Mykhailivka by Monday, 3 October, morning. When the VKS attempted to intervene, it quickly lost a Su-25, somewhere in the Novovoskresenske area.

By the time, the ‘regrouping’ turned into a rout, with the Russians abandoning Ukrainka and Bilvaivka, and fleeing south: as of yesterday, Ukrainians have liberated Novooleksandrivka, Havrylivka, and the Russians — after blowing up the local bridge on the T0403 road — abandoned even Dubchany, prending ‘complete and successful regrouping in Beryslav’.

Further east, as a sign of its goodwill, and in confirmation of Shoygu’s statement that everything is going along the plan, the VDV regrouped from Arhanhelske and Myrolyubivka.

The 35th Naval Infantry seems to have had a had a bad start when one of its columns was pinned down by the Russian artillery, and lost a number of vehicles (this video is played up and down the Russian social media for at least three days now). However, eventually, it came through and seems to have liberated Davydiv Brid, capturing a few Separatists.

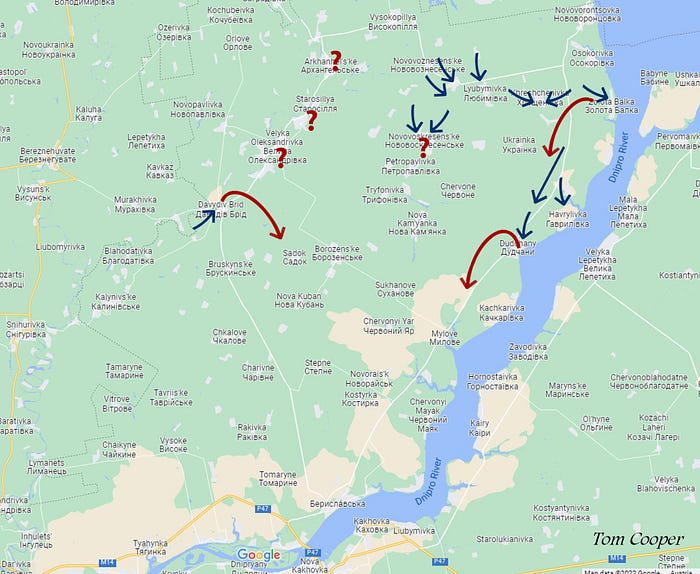

Map of the ZSU operation in northern Kherson since 2 October. Mind: this was drawn yesterday, when it was not yet clear that the VDV ‘regroupped’ from Arhanhelske, and then abandoned all of its positions along the northern Inhulets river (that’s why the three question signs over its positions there).

Map of the ZSU operation in northern Kherson since 2 October. Mind: this was drawn yesterday, when it was not yet clear that the VDV ‘regroupped’ from Arhanhelske, and then abandoned all of its positions along the northern Inhulets river (that’s why the three question signs over its positions there).The Game of Seek and Hide

Now, how comes all of this?

In reaction to quite a few questions of the last few days, let me try to explain how is the war in Ukraine fought, how certain things ‘work’ (or not at all), perhaps even what it is to serve as a ‘soldier’ there — whether in the infantry, armoured/mechanised formations, artillery, logistics or else.

Foremost, plenty of people seem to wonder ‘where are tanks’, and — even after seven months of this war — can’t wait for something like ‘big mechanised formations to run sweeping manoeuvres’, drive through enemy positions shooting broadsides like line-ships of the Napoleonic times (or, should I say: Nelson’s times?) as they go… And if tanks do not do that, or if a few of them get shot to pieces whenever they try, then the conclusions are getting rather hysteric. In style of: ‘tank is obsolete’…

Beg your pardon, everybody: this is simply not how the ‘war works’. It didn’t work that way even in France of mid-May 1940. No surprise it doesn’t now.

The battlefield in Ukraine is dominated by one thing. Two things, if you like.

….and then ‘not just some UAV-guided artillery’, but UAV-guided artillery networked with help of automatic tactical management systems (ATMS) — like Kropyva/Urtica (Ukraine) and Sozvezdiye/Constellation (Russia).

That means not only that both sides are deploying ‘plenty of artillery’: both the Russians and Ukrainians are deploying hundreds of UAVs on a constant search for enemy troops and vehicles. With help of ATMS, these UAVs are in constant contact with field headquarters. As soon as UAVs find something of particular interest: the object in question is subjected to artillery fire.

Unsurprisingly, UAVs — no aircraft and no helicopters — are the primary target of air defences on both sides, and both are shooting down UAVs in droves, every single day. Whenever they fail to do so, whoever and whatever is found by an UAV within 10–15km from the ‘frontline’, is shelled by artillery in a matter of 1–5 minutes.

This is getting so far that there are times and sectors of the frontline where Ukrainians — who, arguably, are better equipped with UAVs — are spending 30, 40, 50% of the flight time of their UAVs to run reconnaissance of their own positions, just in order to make sure these couldn’t be found by the Russian UAVs.

This is why artillery of both sides is hiding most of the times. Yes: it’s frequently hiding even when involved in fire action.

Sometimes, this is reaching such proportions that Ukrainians are protecting their ‘most precious’ self-propelled artillery pieces 1-for-1 by such rare stuff like German-made Gepard Flakpanzer: whenever the artillery piece in question goes into fire action, the Flakpanzer is responsible to protect it — from enemy UAVs, and thus from enemy artillery.

In turn, UAVs are foremost searching for enemy artillery. Whenever they find some, this is shelled until either destroyed, or until it runs away outside the range. That’s what they call ‘counter-battery action/fire’.

Sometimes, enemy artillery is not going to run away when targeted, but — preferably with help of UAVs, but sometimes with support of artillery radars — shoot back at the artillery that’s shooting at it. That’s what they call ‘artillery duels’.

Second principal target of artillery are fortifications: especially fortifications behind the frontline, like those used to protect headquarters, specific objects and/or vehicles — but also fortifications along the frontline. Fortifications are constructions designed to protect people and equipment: they can be anywhere between ‘relatively primitive’ (like a ‘simple, shallow trench’), and ‘elaborate’ (say, a bunker made of 1m thick concrete, with specially designed openings for fire-arms, which can be shut down with help of armoured covers etc.).

This is why whoever only can is doing his/her best to hide fortifications — to camouflage them, foremost with help of vegetation, or by ‘embedding’ them into terrain and vegetation; and why, in turn, why whoever only can is trying to find such objects, and then shell them, too.

Now, pay attention: I’ve just spent more than a full DIN A4 page (and that in fonts 10) to explain ‘just the basics’ — and haven’t even come as far as to ‘explain that with infantry and/or tanks’.

The reason is that these are the ‘fundamentals’ of this war. This is how 80–90% of action is fought — both by the Russians and Ukrainians. Should there be any doubts, invest 5–10 minutes of googling around to find articles quoting 80–90% of casualties on either side being caused by artillery.

Bottom line: most of the time, and regardless if on the move or standing still, everybody is hiding: hiding from UAVs, and from artillery.

Now, as a retired Lieutenant-Colonel of the US Marines nicely commented in a private chat, yesterday, this is where Ukrainians are enjoying quite some advantage. Reason? Whether motorised or airborne, the Russian infantry is ‘vehicle tied’. Its troops rarely venture more than 100 metres away from their vehicles. Because these vehicles are easy to detect and track — whether by radars, by infra-red or low-light TV systems — the Russian infantry is quite easy to find, too. On the contrary, Ukrainian infantry is frequently operating ‘miles away’ from its supporting vehicles. I.e. ZSU infantry is much harder to find.

So, where’s then the tank’s place in all of this?

Guess what: they’re hidden. Scattered and hidden, to be more precise. Indeed: most of the time, and whenever within 10–15km from the frontline, they’re just as well-hidden as anything else that wants to survive.

A tanker of the 128th Mountain during a break. As usually, his tank is hidden between the trees.

A tanker of the 128th Mountain during a break. As usually, his tank is hidden between the trees.The reason is that tanks (and other armoured vehicles) are big, loud vehicles, raising dust whenever they move — and the human eye is made to detect movement first. Thus, whenever a tank moves, it’s easy to detect. Especially so by any decent UAV, ‘hoovering’ 500–1,000 metres above ‘its own side’ of the frontline. Put two, three, six, ten or more tanks (or other armoured vehicles) together, and they’re hard not to detect: ‘even a blind man’ — is going to hear them, at least. Even if organised into a column or a wide front, and well spread out, tanks are usually detected well before reaching the frontline: especially on the frontline as saturated with reconnaissance UAVs as those in Ukraine, and definitely well before they can bring their own weapons to bear.

Usual result is unavoidable: the mass of tanks that gets destroyed or disabled are destroyed or disabled by artillery while still some 2,000–5,000m behind the frontline. The only way to bring them any closer to the frontline is to first destroy enemy UAVs, or at least run counter-battery action and thus either suppress or force the other side’s artillery to withdraw. To prevent the enemy from detecting tanks early, and then to prevent the enemy from targeting tanks by artillery. ….alternatively, one can always drive them out — and then watch them being destroyed, one after the other.

Once tanks are within 2000m from the frontline, they’re entering the range of enemy mortars (at least those calibre 120mm), and anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs). Mortars are like artillery, just shorter-ranged: foremost, their bombs are travelling along ballistic trajectory and thus hitting top armour of tanks, where this is at its thinnest. Be sure: a single hit by 120mm bomb is going to disable — if not outright destroy — any of tank types deployed in this war (and it would do exactly the same with any of Western tank-types, too).

As next, there are ATGMs: ATGMs operated by the Russians and Ukrainians have a range of 4,000–5,000 metres. This is a longer range than the one of 125mm smooth-bore guns that are the primary armament of tanks deployed on both sides of this war, tanks like T-64, T-72, T-80, and T-90 (arguably, that gun has a range of out to 11,000 metres, however: in the direct-fire mode, this is down to about 1,500m).

Means: by the point in time when they are within 2,000 metres of the frontline, tanks are almost certain to come under both the fire of enemy artillery, and mortars, and ATGMs.

As next, there are mines. Mines are ‘not sexy’: any sane soldier is despising them. They are destroying, killing, at least maiming in a way widely perceived as ‘perfidious’. Minefields are always positioned where the least expected, and anything else than ‘easy to find’: nobody is as crazy as to clearly mark a minefield for the enemy. In this war mines are used in insane numbers. Just one example: about a week ago, Ukrainians have started de-mining an area of about 1,000 square kilometres recently liberated from the Russians: While de-mining the first square kilometre, they have found 12,000 mines.

Favourite way of defence on both sides of this war is to combine all of this: artillery, mortars, ATGMs, and mines. Say: let the enemy drive out his tanks into an attack, then let these run into a minefield at a selected, exposed point, then smash him with artillery, mortars and ATGMs. They call that a ‘kill zone’. We’ve already seen dozens of videos of this happening to the Russian tankers in particular: no need to have any doubts, in more recent days the Russians did the same — and not only a few times — to Ukrainian tanks, too. Afterwards, we get to see photos of this kind:

Four Russian main battle tanks knocked out by a combination of mines, ATGMs and artillery fire, somewhere in the Donbass.

Four Russian main battle tanks knocked out by a combination of mines, ATGMs and artillery fire, somewhere in the Donbass.Under these circumstances there’s no place for ‘chivalry tank-vs-tank battle’. This is no war of kamikaze-troops: with few (usually: alcoholised or panicked) exceptions, nobody is running around screaming ‘kill me, kill me first’. And, why should the defending side expose its tanks to the assailant’s artillery by driving them out of their hideouts — if assailant’s tanks can get smashed to pieces by the artillery, and — if artillery is not enough — then by a combination of artillery, mortars, ATGMs, and mines, and that from safe distance, without own losses…?

Even in the few cases where tanks did get as far as to engage enemy tanks, artillery and ATGMs became involved in a matter of 1–2 minutes, always with the same result: tanks must run away, or they’re knocked out. Unsurprisingly, the number of documented ‘classic tank-vs-tank battles’ in this war can be counted on fingers of one, perhaps two hands. Here a good example:

And mind: only then, once all of this has happened, is one or the other side serving us selected, ‘spectacular’ videos, shown tanks of the other side getting pulverised.

Should this mean ‘tank is obsolete’?

Nope.

Foremost, it means that neither side is keen to show us videos when its own forces have suffered losses.

After that, it’s ‘just so’ that in the first seven months of this war, neither side found a solution for the superiority of artillery. That’s the core reason: like any other weapons system, tank ‘works’ when deployed in so-called combined arms operations: essentially an effective system of fighting a war, including tanks, artillery, infantry etc.. If left at its own, it’s as useless as any other weapon system deployed at its own.

Sure, next to nobody else (bar Iran and Iraq of 1980–1988) has fought a war of this volume in ages, and thus, actually: there are no comparable experiences. Indeed, the modern-day ‘social media generation’ simply does not know wars of this size and scope. But, it can be assumed that specific other belligerents — especially some ‘Western/NATO’ party — would seek to neutralise the enemy artillery with help of air power. See: fighter-bombers equipped with precision guided munition, or mass deployment of loitering precision guided munition (PGMs). So far, Russia and Ukraine’s air defences, and lack of advanced PGMs have prevented the other side’s air power from providing effective close air support Despite some Western deliveries to Ukraine, and recent Iranian deliveries of loitering PGMs, neither side seems capable of deploying these in sufficient numbers to change the situation.

Overall: artillery continues dominating this war and I do not see this changing any time soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment