ORVILLE SCHELL

By the time my plane touched down in Taiwan, The Economist had labeled the island “the most dangerous place on earth.” This was shortly after Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, had visited Taipei — an offense in the eyes of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing that justified an unprecedented military show of force.

During the first three weeks of August, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) aircraft intruded into Taiwan’s airspace more than 600 times, carried out six “live fire” exercises around the island, and for the first time fired missiles right over the island and into Japan’s exclusive economic zone. Many feared a Chinese version of Vladimir Putin’s “special military operation” in the Ukraine was in the making.

I had traveled there as part of a delegation from Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, with which the Asia Society has a joint Taiwan project examining microprocessors and the growing tensions in the U.S.-Taiwan-China triangle: What will happen to the world’s semiconductor supply chains if China were to blockade or invade Taiwan?

The delegation was impressively credentialed and well suited to our investigation. It was headed by Adm. James Ellis, who’d led two U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups into the Taiwan Strait in 1996, and included: Michael McFaul, a former U.S. Ambassador to Russia; Oriana Skylar Mastro, a scholar at Stanford; Matthew Pottinger, who had served as deputy national security adviser; and Matthew Turpin, a former China director at the National Security Council (NSC).

Since I’d first visited Taiwan six decades before, when hostility across the Taiwan Strait was as intense as it is now, I brought some historical perspective. For I’d begun my own professional life as a China watcher on the Taiwan side of the Strait, then moved to the other as Mao’s China opened up, and now was coming back again to the Taiwan side. Given the parlous state of relations that has developed once again between the two sides, as we arrived, I was seized by a triste sense that I’d become a bit part written into a senseless modern-day Greek tragedy. How, after so many hopeful decades of trying to make “engagement” work, had relations between the U.S., China and Taiwan snapped back to the same hostile state I’d encountered upon first entering this drama?

Back then, Taipei was a ramshackle backwater under the autocratic rule of Chiang Kai-shek. Now, it’s evolved into a prosperous and vibrant democracy and done so in the face of the CCP’s militant insistence that democracy ill-suits Chinese at this stage of their development.

There are no easy answers. But our meetings — which included a straight-forward sit down with the president of Taiwan, many cabinet ministers, CEOs and policy makers — convinced me of three things.

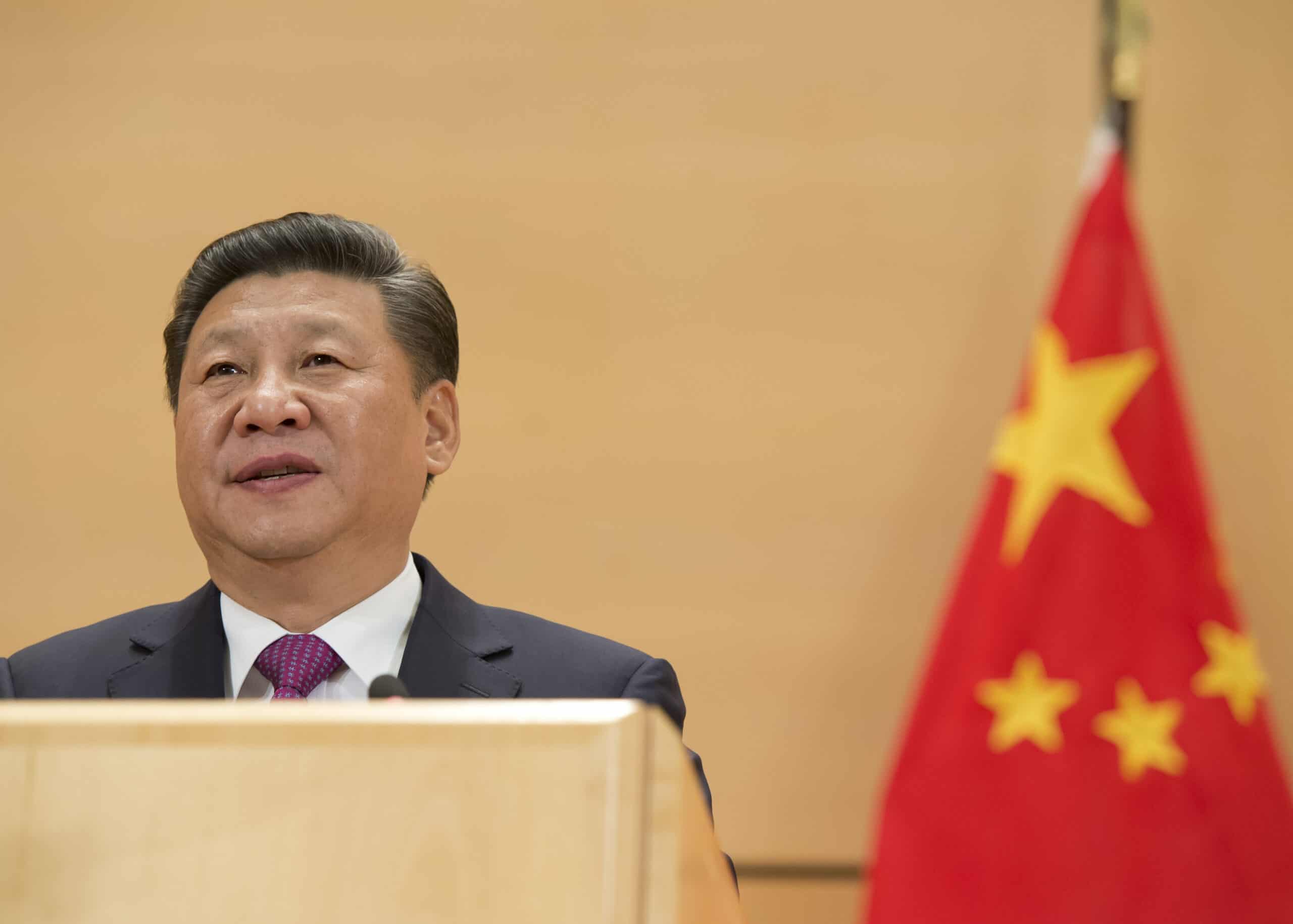

Xi speaking about “China’s complete reunification” at a meeting in Beijing marking the 110th anniversary of the 1911 Revolution. October 9, 2021.

First, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s quest to achieve what he’s dubbed his “China Dream” means that, no matter what, he will relentlessly continue to push for “Taiwan’s reunification with the Motherland.” Like Vladimir Putin’s vision for Russia, Xi wants to become the rejuvenator of his country’s former imperial greatness.

Many years ago, Robert Jay Lifton, the psychiatrist and China specialist, described Mao Zedong’s obsession with such a heroic mode of leadership as a quest for “revolutionary immortality.” Xi now seems to feel that he, too, is being called by history to lead China into another equally epic phase of modern day “rejuvenation.”(复兴)

Second, I came away with a sense that a full-fledged invasion and occupation of Taiwan can only be deterred by enhancing Taiwan’s ability to resist — in effect, making themselves indigestible to Xi’s China. For the most part, this depends on the military and a citizen-based militia being trained and willing to use low-cost mobile weapons systems — what Adm. Ellis calls “a large number of small things” — dispersed in ways that would make it difficult for the PLA to occupy and rule the island.

And third, given both Xi’s almost messianic sense of his own historical destiny and the critical role that regular Taiwanese citizens will surely have to play in defending their island, the logic and virtue of “strategic ambiguity” — seen as the best way to deter conflict in the Taiwan Strait since the Clinton administration — are more important than ever. The policy not only allows the U.S. to signal support without encouraging undue Taiwanese dependency, but also affords Xi room to “save face” and avoid having to respond to a direct challenge from the United States.

For if there is anything to which Xi is allergic, it’s being forced to evince any hint of fallibility as he reaches for his own version of “revolutionary immortality.” If he fails or even appears to backpedal on his promises, he risks being seen as Mao once put it, like “women with bound feet.”

Indeed, the fact that Taiwan, a Han Chinese society just like the PRC, has managed not only to thrive economically, but to function democratically is already a substantial humiliation for Xi. During our visit to Taiwan, I was struck by how profoundly this island has changed for the better since my first stay there in 1961. Despite all its challenges, it has evolved into a prosperous and vibrant democracy and done so in the face of the CCP’s militant insistence that democracy ill-suits Chinese at this stage of their development.

And while it no longer has U.S. diplomatic recognition, Taiwan does have another very powerful partner: the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) — the ninth largest company in terms of market cap in the world. TSMC is a dazzling success, with chip fabs that make 50 percent of all the world’s microprocessors and 92 percent of all its “leading edge” chips.

There are few things more desired by leaders in Beijing than chips and few things more provocative than supporters of independence for Taiwan. Today, the whole world is dependent on Taiwan’s chips, and since 1994 the percentage of Taiwanese people wishing to “move towards independence” has more than tripled.

Of course, China has also changed a great deal in this timespan. But, as I have written before in this magazine, those changes — such as new subways and high-speed rail systems, skyscrapers, highways, and airports and an impressive GDP — have not altered the Communist Party’s fundamental DNA, which codes it to remain fixated on power and control. As the CCP readies itself later this month for the 20th Party Congress and the anointment of Xi with possible lifetime tenure as the country’s Supreme Leader, it’s ever clearer that he sees himself like one of those imperial emperors who proclaimed themselves “grand progenitors” (太祖) and as the latter day successor of Chairman Mao. And just as Mao had written in a 1959 poem that he wanted his “will to become strong” so that he would dare “command the sun and moon to bring a new day,” Xi, too, wants to transform China. And in his view, that involves annexing Taiwan.

When I arrived in Taiwan as a young student from Harvard in 1961, it was a mere 12 years after Chiang Kai-shek had been defeated by Mao’s Communists. To reach Taipei I signed onto a Norwegian freighter and worked as galley boy as it made a circuitous six-week trans-Pacific passage via Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji, New Caledonia, and New Guinea.

A 1971 propaganda poster with the caption, “People of the world unite and defeat the American aggressors and their running dogs!”. Credit: UCSD Special Collections & Archives

A 1971 propaganda poster with the caption, “People of the world unite and defeat the American aggressors and their running dogs!”. Credit: UCSD Special Collections & ArchivesOnce in Taipei, I moved into a spartan National Taiwan University dorm. To escape our suffocating room in the summertime, me and my roommates sometimes took a bus to a fishing village perched on a lovely beach south of Keelung. There, we laid out on the sand under the star-filled night sky and, although it was then illegal to do so, tuned our battery-powered transistor radio to the broadcasts that crackled across the Taiwan Strait from Mao’s China. Breathless with political zealotry, these Communist diatribes sounded almost like fundamentalist sermons raging against the wages of sin. For me there was something electrifying about the vehemence with which they decried “American imperialism and its running dogs” and glorified Chairman Mao.

Being a student of Chinese history, I knew how the Party’s mindset had been influenced by Lenin’s theories on the evils of imperialism and then been super-charged by Mao’s own narrative of China’s victimization, exploitation, oppression, occupation, and humiliation at the hands of “the great powers.” But, what really drew me to these broadcasts was the way they suggested that tectonic history was being made just across the inky black water.

The same could not be said of Taiwan, which back then seemed parked on an historical siding with nothing of much consequence happening. As one of the few foreigners then studying there, I was invited by the Republic of China’s Anti-Communist Regain the Mainland International Kuomintang Save the Country Youth League (中华民国反共复国国民党国际青年救国团) for tea with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. To get to his Baroque-style Presidential Palace, a relic of the Japanese colonial era, I rode my bike down Ren Ai Lu past billboards proclaiming his intention to “counter-attack the Mainland (反攻大陆),” depose the “Communist bandits (共匪),” and restore Nationalist rule to China.

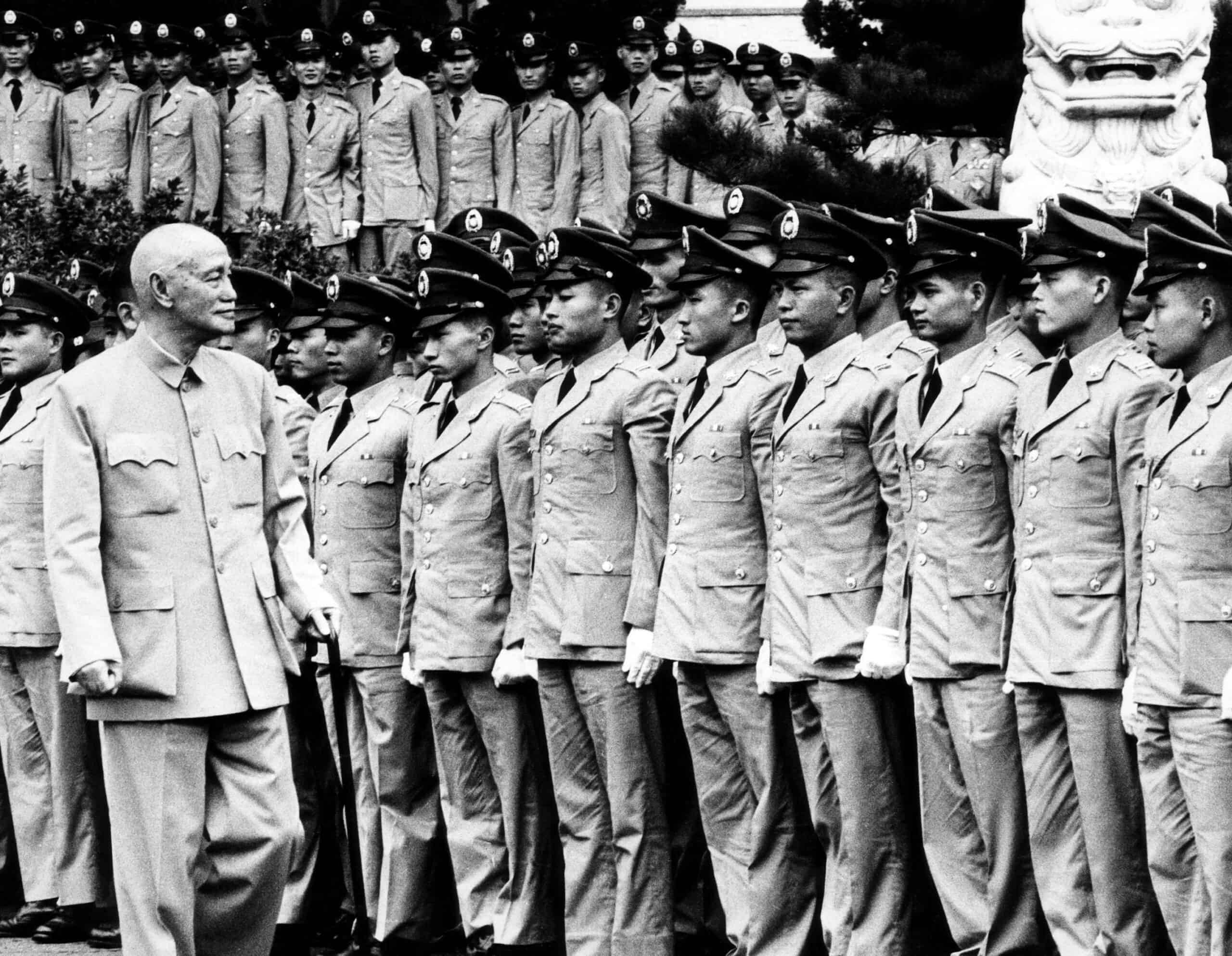

Chiang Kai-shek inspects uniformed students at the commencement of five service schools, 1970. Credit: Everett Collection Inc via Alamy

Chiang Kai-shek inspects uniformed students at the commencement of five service schools, 1970. Credit: Everett Collection Inc via AlamyBut despite such bravado, the “Gimo,” as Chiang was known, was something of a disappointment in person. Not given to smiling, he spoke with a high pitched Ningbo accent that was almost unintelligible to me, and in the flesh he radiated a dispiriting air of tragic misfortune. After all, he’d once been a Big Leader consorting with the likes of Winston Churchill, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Joseph Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Now, expelled from the China big-top, here he was, marooned on this small flea-shaped island unable to compete with the mythic power of Mao’s dramatic, if inaccessible, revolution just across the Strait.

Chiang Kai-shek’s fall was marked by three inflection points. The first came in 1949 when he lost the Chinese Civil War and fled to Taiwan. The second came in 1972, when President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger heaved to in Beijing and teamed up with Mao and Zhou Enlai against the USSR. And, the third came in 1979, when President Jimmy Carter invited Deng Xiaoping to Washington, severed diplomatic relations with Taipei, and extended recognition to Beijing.

Richard Nixon and Zhou Enlai, February 25, 1972.

Richard Nixon and Zhou Enlai, February 25, 1972.Credit: White House Photographer

But even though Taiwan had been cut adrift, it not only managed to survive, but ended up surprising the world by economically flourishing and becoming both democratic and well-run. Beijing, by contrast, careened into violent revolution before finally prospering precisely because it was welcomed into the global fold, with nine U.S. presidential administrations supporting a policy of “engagement” for more than four decades.

… as the artist Ai Weiwei has astutely observed, even throughout this period of tremendous change, one of the imperatives that grew out of the CCP leadership’s deep insecurity and paranoia was a “constant need for an enemy against which to define itself.”

I did not reach Beijing until 1975, 14 years after my first visit to Taiwan. At the time, Mao still reigned with God-like status. But, I was mystified from the day I arrived by how impossible it was to connect with Chinese counterparts. Unlike Taiwan where I’d made many friends easily and even found a Chinese girlfriend, in the PRC I made no friends and left feeling as insoluble as oil in water. Despite Nixon’s rapprochement, in Mao’s China the U.S. was still enemy-in-chief and this bitter reality infected every interaction Americans had with Chinese there. What’s more, I detected no discernible signs that this revolutionary society had the seeds of change within it — Mao’s China seemed absolute, frozen, and eternal.

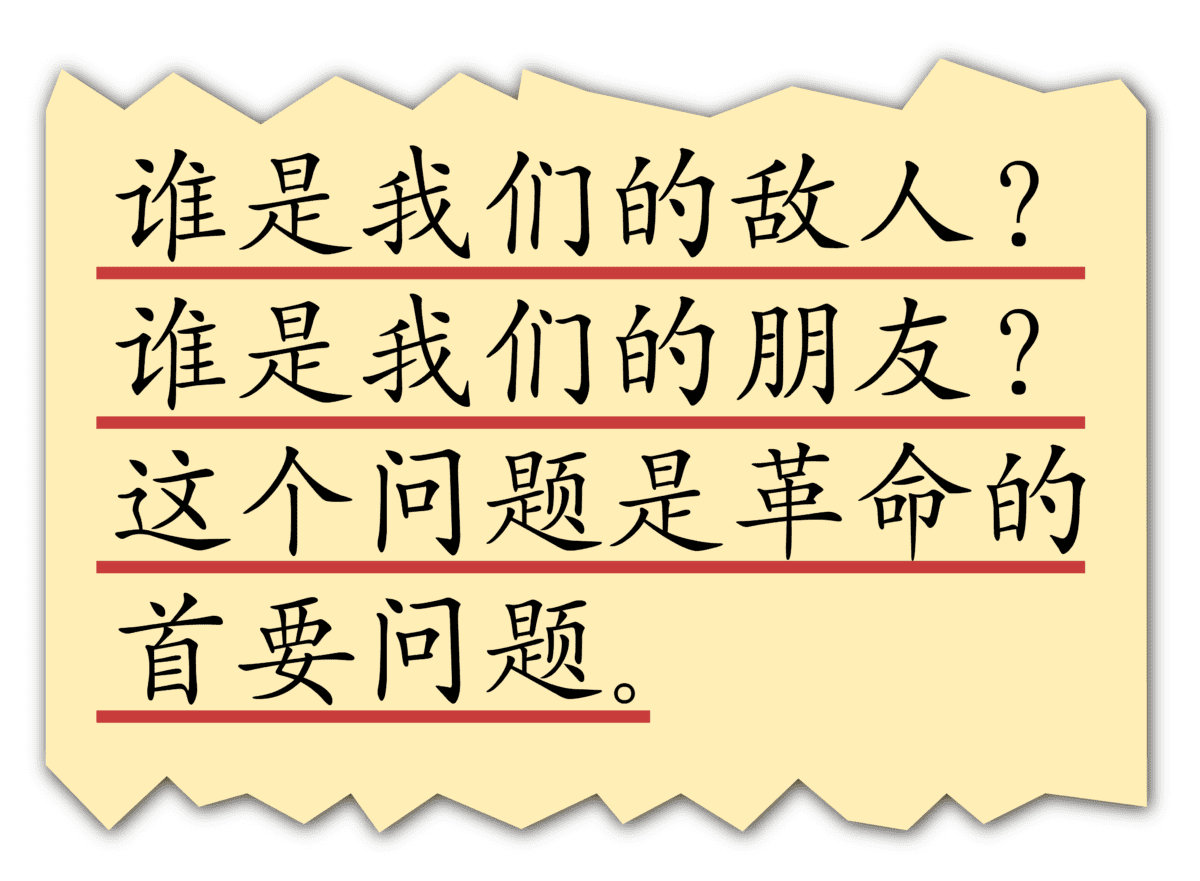

Mao’s “Who are our enemies?” quote, from “Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society” (March 1926), Selected Works of Mao Tse-teng, Vol. I, p. 13.

Mao’s “Who are our enemies?” quote, from “Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society” (March 1926), Selected Works of Mao Tse-teng, Vol. I, p. 13.As Lifton had written of that period, there is something uniquely unyielding about the grandiose transformative dreams that attach themselves to Leninist leaders like Mao and now Xi. Because they view themselves as coterminous with the parties and states they lead, they often see threats to them — imagined or real — as threats to the whole political system. Lifton observed that sooner or later every such tyrant reaches a “psychological stage” when one “cannot dispense with one’s hatred” and “cannot give up one’s enemies.” Mao was himself so personally fixated on “enemies,” he famously began one of his essays by asking: “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution.”

Of course, Mao’s death just a year later, in 1976, proved that there were, in fact, incipient forces for change still latent beneath the surface of things. And, it wasn’t long before Deng Xiaoping was “rehabilitated” from Mao’s revolutionary doghouse and began ushering in a bold new agenda of “reform and opening.” (改革开放).

But as the artist Ai Weiwei has astutely observed, even throughout this period of tremendous change, one of the imperatives that grew out of the CCP leadership’s deep insecurity and paranoia was a “constant need for an enemy against which to define itself.” Enemies of the CCP may come and go, Ai notes, but “the fundamental need for an enemy has never changed.”

Orville Schell (far left) and the rest of the delegation from Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, meeting with Tsai Ing-wen (center) in Taipei, Taiwan, August 23, 2022. Credit: 總統府 via Flickr

Orville Schell (far left) and the rest of the delegation from Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, meeting with Tsai Ing-wen (center) in Taipei, Taiwan, August 23, 2022. Credit: 總統府 via FlickrBACK TO THE BEGINNING

When our delegation went to visit Tsai Ying-wen, the current “president” of this stateless island of 23 million people, I found myself back in the “presidential palace” where I’d met Chiang all those years ago. And although the experience underscored what an intractable problem Taiwan has been in the China equation, it also underscored the extent to which Taiwan has changed both in terms of the Chiang Kai-shek era and the Chinese mainland.

Tsai arrived with none of the pomp or circumstance that usually follows Xi Jinping. She just glided into our conference room through a side door wearing unpretentious dark slacks and a simple blue jacket. Then, standing under a portrait of Sun Yat-sen, the “Founding Father of the Republic of China,” she calmly welcomed us in excellent English — something PRC officials rarely do, even if they can, lest speaking English show too much deference.

President Tsai Ing-wen at the 38th Han Kuang Exercise, Taiwan’s annual military exercise, June 26, 2022. Credit: 總統府 via Flickr

President Tsai Ing-wen at the 38th Han Kuang Exercise, Taiwan’s annual military exercise, June 26, 2022. Credit: 總統府 via FlickrHer directness was striking. There was none of the hollow official-ese (空话), sophistry or avoidance that so often makes dialogues with leaders on the other side of the Strait so rote and tedious. The recent live-fire PLA exercises had helped convince her to call for raising Taiwan’s defense budget by 14 percent and for a full year of military conscription for men.

For her, “confidence” is the key to the island’s resilience, and she tells us she wants to see “the Taiwanese people feeling confident that the U.S. will intervene, but not overconfident.”

This sentiment was repeated often during our trip and underscores the dual role of “strategic ambiguity” as U.S. policy. Lately, President Joe Biden has made several statements that, on the surface, seem to imply that U.S. policy was moving away from ambiguity to “strategic clarity.” Most recently, for example, he appeared on 60 Minutes and, when asked whether U.S. forces would defend Taiwan if it was attacked by China, replied, “Yes, if in fact there was an unprecedented attack.”

“U.S. forces — U.S. men and women — would defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion?” pressed the anchor incredulously.

“Yes,” affirmed Biden.

But for every time Biden says the U.S. will defend Taiwan, someone from his administration walks it back. Indeed, however off-the-cuff Biden’s statements may have seemed, one can view them not as an abrogation of “strategic ambiguity,” but as expressions of a more evolved kind of ambiguity, one that endows the concept with a cryptic new set of teeth — all without allowing Taiwan to feel “overconfident” or forcing the Chinese to respond to the affront of “strategic clarity.”

Tsai herself, while rarely mincing words, is mindful of backing Beijing into a corner. Although she is in the Democratic People’s Party (DPP), which once flirted with independence, she has steadfastly avoided making statements that might provoke Beijing and carefully walks a fine line — but one that is of utmost importance.1

To maintain his myth of omnipotence, Xi must persuade, or force, Taiwanese to join the other pieces of Qing empire real estate — Tibet, Xinjiang, Macau and Hong Kong — that have already been annexed into his Communist imperium. But what Xi wants of Taiwan is the island’s territory, not its insubordinate people. As an expression making the rounds in Beijing chillingly puts it, Xi wants to: “Keep the island, but not keep the people” (留岛不留人民).

Xi’s ambitious day dream of techno-autocracy and reunification by force might now plunge Taiwan, China, the U.S. and the world into yet another equally ruinous tragedy.

The problem is that these insubordinate people seem more and more ready to put up a fight. As a result of Beijing’s saber rattling, support for “reunification” has shrunk from 29 percent in 2020 to less than 2 percent now. And, more than 70 percent of Taiwan’s populace now say that, if invaded, they’re ready to fight by employing almost Mao-like guerrilla warfare tactics — what’s come to be known as a “porcupine strategy.”2

Indeed, while Pelosi’s trip may have angered Beijing, even giving Xi a pretext to ramp up military exercises, it also helped galvanize Taiwanese, and the world, into finally recognizing that the status quo in the Taiwan Strait of the past few decades is now gone and China is not afraid of using military force.

An amphibious landing drill conducted by China’s Navy, in Shandong Peninsula, August 24, 2005. Credit: Li Gang via AP

An amphibious landing drill conducted by China’s Navy, in Shandong Peninsula, August 24, 2005. Credit: Li Gang via APAfter taking off for home, our plane flew up Taiwan’s west coast, and as I looked out the window, there below was the very beach on which so many years ago I’d sprawled under the night sky engrossed by the radio broadcasts coming across the strait from Mao’s forbidden redoubt. Seeing this once remote beach now skirted by a modern highway and encrusted with what looked like warehouses was a reminder of Taiwan’s great progress. However, as that arc of sand slipped away beneath the wing of our plane, I was also dispirited to think that this very beach was most certainly on PLA maps as a prime site for a PRC amphibious landing and that the success stories of both Taiwan and China could now be sabotaged by one reckless decision to take military action.

While such a move would be ill-advised, the former British diplomat and China specialist Charles Parton recently reminded us that such decisions are neither new nor rare for ambitious leaders longing to leave their marks on history. In a piece on Taiwan, Parton recalls the story of Croesus, the very wealthy ancient King of Lydia, who consulted the Delphic oracle before going to war, which prophesied: “If Croesus goes to war, he will destroy a great empire.” Despite this warning, Croesus did go to war and did destroy his empire.

“Leaders do not always act wisely,” concludes Parton. “Hubris or desperation are not unique to the ancient world.”

Xi Jinping speaking at the United Nations Office at Geneva. January 18, 2017. Credit: UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferré via Flickr

Xi Jinping speaking at the United Nations Office at Geneva. January 18, 2017. Credit: UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferré via FlickrIndeed, the more I watch Xi, the more he seems destined to become another such tragic hero — a smart, overweening, ambitious leader unable to stop himself from putting the very thing he professes to care about most (his country) in mortal peril. Just as Mao’s overwrought dreams of class struggle and global people’s war led to the deaths of tens of millions and the ruination of his revolution, Xi’s ambitious day dream of techno-autocracy and reunification by force might now plunge Taiwan, China, the U.S. and the world into yet another equally ruinous tragedy.

In writing about Mao, Lifton, too, reminded us that “it is the nature of great men and great revolutions to be dissatisfied with their accomplishment, however extraordinary, and to plunge into realms that even they cannot conquer. If this be the meaning of tragedy, the tragedy is not merely theirs.”

No comments:

Post a Comment