Alissa de Carbonnel

President Vladimir Putin’s planned annexation of parts of Russian-occupied Ukraine, after sham referendums there, is at least as dangerous a moment in the war as the marathon televised spectacle that prefaced Russia’s invasion in February.

Of course, things have not gone as Putin planned.

Back in February, he sought to justify the invasion in an angry speech laced with legal verbiage coupled with a pre-recorded show of support from the country’s top brass. The only thing genuine in Putin’s effort to frame the “special military operation” as something other than naked aggression was Putin schooling the head of his spy service, Sergei Naryshkin, as he flubbed his script and said he backed the proxy states in east Ukraine becoming part of Russia.

Naryshkin was half a year too early and too mean in his ambition. With its invasion, Russia had planned to swiftly decapitate the political leadership in Kyiv, occupy a huge swath of territory, and exercise influence over a newly friendly Ukraine, perhaps leaving some troops there. Ukraine’s dogged resistance culminating in the lightning recapture of territory in the Kharkiv region has put the Kremlin on the back foot, forcing it to rush forward haphazardly with what has emerged as its plan B.

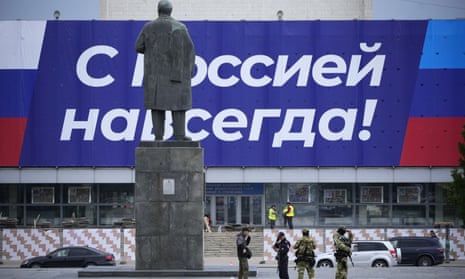

The would-be referendums in Russian-controlled parts of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – precursors to a planned formal annexation this week – were hurried and ugly, held at gunpoint and with shells exploding in the distance. They lacked the Potemkin pageantry of similar so-called ballots in Crimea in 2014, which were at least accompanied by efforts to entice voters with promises of higher pensions and Russian investment.

This time, in its urgency, the Kremlin appears to have dropped all but the barest attempts to make the referendums look convincing, opting instead for brutality. So why bother at all?

There was a domestic and an international agenda to the mock vote.

Putin’s main audience is at home. The day after news of the referendums, he ordered a military mobilisation – a deeply unpopular move that Russia has long avoided despite lacking manpower on the front. Russian disinformation has not always had to be sophisticated to find purchase, but people being asked to kill or die – or send their loved ones to do so – are more apt to ask why.

Despite Russia’s harsh crackdown on dissent, protests have erupted across the country and at least 200,000 Russians have fled the country since Putin’s announcement, often spending their life savings on hard-to-get plane tickets out or waiting for hours in queues at the border. Annexation aims, in one pen stroke, to transform the conflict from a faraway, limited “special military operation” that Russians could be jailed for even calling a war, into a battle to defend Russia’s own territory, not Ukraine’s.

Internationally, the other objective is to up the ante in the confrontation with Ukraine and its western backers. Putin’s announcement of the mobilisation was accompanied by the threat of nuclear strikes if Ukraine continued to retake its own lands. Putin – who attaches great importance to the Soviet-style patina of legality he apparently believes the referendums afford, however Kafkaesque – is aiming to make such threats credible and thus coerce capitulation. They also serve to stoke the false war narrative Russia is spreading via social media and digital diplomacy abroad, where it has had some traction.

All of this amounts to a dangerous new phase of the war.

Ukraine is fighting for its survival. It is not worried about escalation and has no intention of backing down. Its western backers do rightly fear the conflict spiralling into a Nato-Russia standoff. But Putin’s attempts to cow Ukraine will probably galvanise western support at a time when it risked flagging as politicians grapple with inflation and energy woes. So the war will rage on.

Putin has jettisoned diplomacy. While he likes to keep his options open, those are limited. Russia may be preparing its forces for a new offensive in the winter. If it seizes new territories, it could look to repeat the illegitimate referendums there. And it could still, most alarmingly, widen its strike targets in Ukraine or, in a desperate move, act on Putin’s nuclear threat.

US and European leaders are absolutely right to call out Moscow’s threats as risking catastrophe for Russia itself and to swiftly denounce the referendums as the sham they are, including by introducing a UN resolution. This last, couched as a vote on the principle of territorial integrity, will hopefully garner support from countries in the global south that have been less inclined to take sides.

It’s a critical moment for the world, including for media, factcheckers and big tech companies, to redouble efforts to counter Russian disinformation. Even reporting on the referendums as if they were any other vote risks lending the kind of legitimising narrative that abetted those politicians sympathetic to Russia or wary of a fight. And, instead of faulting Russians, especially those who have fled rather than fight in a war they don’t agree with, countries should be offering them safe harbour. Doing so deprives Moscow of troops and aligns with every humanitarian principle.

Ultimately, western states must continue walking the tightrope between supporting Ukraine and perilous escalation. The more outrageous Russia’s provocations, the more important it will be to respond with the balance of prudence, unity and resolve that has marked the west’s response to date.

Alissa de Carbonnel is deputy programme director for Europe and Central Asia at the International Crisis Group. Oleg Ignatov, Crisis Group’s senior Russia analyst, also contributed to this article

Thank you for joining us from India.

Where will it all end? The conflict in Ukraine appears further than ever from resolution. Nuclear threats, mass graves, the sense that both sides are “all in”.

It’s our job at the Guardian to decipher a rapidly changing landscape, and report the facts in sober fashion, without getting carried away. Our correspondents are on the ground in Ukraine and Russia and throughout the globe delivering round-the-clock reporting and analysis during this fluid situation.

We know there is no substitute for being there – and we’ll stay on the ground, as we did during the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the first Russo-Ukrainian conflict in 2014. We have an illustrious, 200-year history of reporting throughout Europe in times of upheaval, peace and everything in between. We won’t let up now.

Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. We’d like to invite you to join more than 1.5 million supporters from 180 countries who now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital to establish the facts: who is lying and who is telling the truth.

And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future.

No comments:

Post a Comment