THERESA HITCHENS

WASHINGTON — Though the recent tumult over whether Elon Musk’s SpaceX would continue to fund the operation of its Starlink satellite service in Ukraine appears to be over for now, an uncomfortable question remains: If for some reason Starlink is not available, who else might the Pentagon, or Ukrainian forces for that matter, be able to turn to?

While there are other satellite communications firms providing internet connectivity from space, experts say that, at least in the short term, there are few that provide both the wide global coverage and inexpensive, highly mobile and easy-to-use receiver terminals that have made Starlink a vital part of Ukraine’s war against Russia.

“There really aren’t any great substitutes here. I mean, this is why [Starlink has] been such a game changer, because there’s not been anything like it before,” said Tim Farrer, an industry consultant. That situation isn’t likely to change, he added, for “maybe about a year” — meaning that for the moment it is almost the only game in town for keeping the embattled Kyiv government and the Ukrainian military connected.

CNN reported Oct. 14 that SpaceX in September wrote to the Pentagon asking payment in the future for the satellite communications terminals and internet access the company up to now has been donating to the embattled Ukraine government and military. According to CNN, SpaceX’s director of government sales said “We are not in a position to further donate terminals to Ukraine, or fund the existing terminals for an indefinite period of time.”

SpaceX’s mercurial founder Elon Musk on Saturday seemed to reverse course in a typically colorful tweet, and Monday went further, tweeting that the company has withdrawn its request.

Pentagon Press Secretary Pat Ryder on Monday said up to now the Pentagon has not paid Starlink anything for the company’s services in Ukraine — even if CNN suggested others in the US government had — but he reiterated remarks by his deputy on Friday confirming that the Defense Department is in conversations with SpaceX, as well as others, about how to ensuring continued Ukrainian access to satcom.

Beyond Ukraine, DoD has been rushing to contract Starlink not just for experiments to substantiate its Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) effort, but also to provide battlefield connectivity to commanders in the field. Nonetheless, questions about the company’s near market-lock on space-based internet services for military use have been ricocheting around Washington and other allied capitals — with some wondering what options they have aside from the Musk-backed system.

The Alternates To Starlink

In his Monday, comments, Ryder acknowledged other providers, saying “When it comes to the broader issue of providing satellite communication to Ukraine, we are in discussions with SpaceX, as well as other companies, to look at how to best provide that service.”

While Ryder did not provide details about those other providers, there are at least a handful of companies that today offer internet connectivity from space. These include Viasat, OneWeb, SES, Iridium, Inmarsat, Eutelsat and Avanti.

London-based OneWeb intends to have begin global operations next year, after all 648 of its LEO satellites are on orbit. (OneWeb)

These aren’t hypothetical systems. For example, ViaSat’s KA-SAT service is currently operating in Ukraine, as well as providing free wi-fi to Ukrainian refugees in Slovakia, and the firm said on Friday that it is working to rapidly provide additional services. (Spokesperson Dan Bleier told Breaking Defense on Monday that the company couldn’t provide more details at the moment.)

“Translator” payloads are necessary because many of today’s commercial remote sensing providers do not, and will not, have the ability to equip their satellites with optical inter-satellite links (OISLs) required to link to the agency’s Transport Layer birds, said SDA Director Derek Tournear.

But experts say each of those providers face near-term challenges in competing directly with SpaceX — which has global coverage with almost 3,500 satellites in low Earth orbit at an altitude of about 550 kilometers, and provides cheap receiver terminals that basically are ready to go once you take them out of the box.

Brad Grady, a satellite industry analyst at Northern Sky Research, told Breaking Defense on Wednesday that Starlink has a number of “key advantages” over its closest competitors. These include: “latency, throughput, [and] terminal size/power.”

Satellites stationed in geosynchronous orbit some 36,000 kilometers in altitude — including KA-SAT and those operated by Eutelsat, Intelsat, Avanti, and Inmarsat — can provide world-wide coverage including over Ukraine, but GEO birds have a couple of downsides vice networks in lower orbits.

First, they tend to be more vulnerable to cyber attack, several industry experts noted, as exemplified by Russia’s successful hack of KA-SAT ground terminals in Ukraine right at the start of the war in February. GEO-based networks also have higher latency — the time it takes to downlink and uplink — than those closer to the Earth, because of, well, physics.

Satcom operators in LEO and medium Earth orbit (MEO) also have challenges in meeting Starlink’s capabilities. For example, OneWeb, which is putting up a mega-constellation in LEO to rival Starlink, currently doesn’t operate satellites that cover Ukrainian territory, several sources said, although it has plans to be able to provide capacity there at the end of next year.

“They don’t have the capacity right now,” said one industry expert.

OneWeb last July announced it had started operations covering regions north of 50 degrees latitude (including the Arctic), but according to the company’s website, its full constellation, including satellites that cover lower latitudes, will not be operational until next year. Ukraine lies just below 50 degrees north.

Amazon’s similar network, called Project Kuiper and to comprise some 3,236 satellites, hasn’t even launched yet and won’t begin service until sometime in the 2026 or 2027 timeframe. The launch of the first two satellites was planned for late this year, but has been delayed due to schedule slips in development of the United Launch Alliance’s heavy-lift Vulcan rocket. That launch is now planned for early next year, according to Amazon’s website.

Grady said that in the non-geostationary satellite market, Luxembourg-based telecommunications firm SES’s O3b and future O3b mPower constellations, which are stationed in MEO, come closest to meeting Starlink’s current capabilities. (The company reportedly is a main provider of satellite television in Ukraine and has employees on the ground there.)

A Matter Of Receivers

As Grady and other experts noted, SpaceX’s greatest advantage is that Starlink terminals are low cost, highly mobile and, all-importantly for warfighters, simple to set up and use. GEO networks in particular require large, heavy and expensive terminals. But even many terminals designed for satellite networks in lower orbits haven’t quite matched the specifications for Starlink’s small size, weight and power, known as SWaP.

According to SpaceX’s website, Starlink’s dish antenna weighs about 2.9 kilograms (6.4 pounds) and the terminal has very few moving parts.

“It’s a question of terminals,” industry analyst Farrar said “The closest thing is, there are some portable terminals for Inmarsat Global Express. But they’re not self-installing. They don’t set themselves up. You have to know where to point them at the satellite. They’re really big, and [they cost] tens of thousands of dollars.”

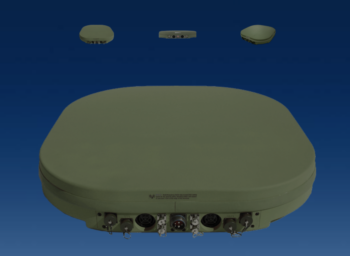

Kymeta’s new Osprey u8 flat-panel antenna can link to satellites in both low Earth orbits and in geostationary orbit. (Kymeta)

A number of companies are working to bring new, smaller flat-panel antennas to the market that are electronically steered, and can pick up signals from satellites in across GEO, MEO and LEO. However, many of those new terminals are not yet ready for primetime — either in development or only being deployed in small numbers.

For example, Intelsat for the first time is developing its own antenna specifically for cross-orbit connectivity, called the multi-orbit, tactical terminal, or MOTT, said David Micha, president of Intelsat General Communications.The reason is that DoD is increasingly interested in “hybrid” architectures for satcom that include satellites in all multiple orbital planes, he told Breaking Defense on Oct. 12.

“That’s under development, 100 percent funded by Intelsat and will hit the market about a year from now. It’s been under development for six or nine months, and it’s going to be really a state-of-the-art satellite terminal,” he said.

Antenna maker Kymeta also is focusing on multi-orbit, steerable antennas, with a particular focus on flat panel antennas for mounting on vehicles, Walter Berger, the company’s president, told Breaking Defense on Oct. 12.

While the Osprey u8 terminal, put on the market in April, is much heavier than Starlink’s, weighing in at 100 pounds, Berger said it sports military-grade cybersecurity. And because it can switch “within milliseconds” from connectivity with LEO sats — Kymeta has an agreement with OneWeb to link to its constellation — to satellites in GEO, he stressed that the Osprey u8 is much harder to jam.

“So, it gives the military that kind of redundant pathway when shit hits the fan. We’re gonna stay connected,” he said.

Berger noted that more than 1,000 of the terminals will be deployed by the end of next year, not just by DoD and the Army, but also by the defense ministries of other nations — although he was coy about which ones.

As for SpaceX’s somewhat understandable concern about long-term losses to the company as the Ukrainian war stretches far beyond the timeframe almost anyone could have imaged in February, the bottom line is going to be just how much of that pain it can negotiate away.

SpaceX’s letter, according to CNN, specified that Starlink operations would cost more than $120 million for the rest of the year and could cost close to $400 million for the next 12 months. Specifically, CNN quoted the letter as saying that about 85 percent of the 20,000 terminals [provided at the letter’s time] in Ukraine were paid — or partially paid — for by the US, the United Kingdom, Poland or private entities. Those entities also paid for about 30 percent of the internet connectivity, which SpaceX says costs $4,500 each month per unit for the most advanced service.

But in an Oct. 7 tweet, Musk said that the company’s operations in Ukraine has cost $80 million and will exceed 100 million by the end of the year.

“I think everyone agrees that if there’s a reasonable cost-based argument that paying for use does make sense,” Farrar said. The problem, he said, is that the company’s “numbers are constantly changing. … I think Elon has made that more difficult rather than less difficult because you don’t normally negotiate your weapons contracts on Twitter.”

No comments:

Post a Comment