Mohammadbagher Forough

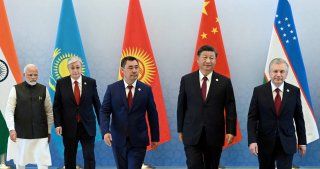

Leaders of Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) countries met in Samarkand, Uzbekistan on Sept 15-16 for an annual summit. It is becoming a common trope in mainstream Western media and think tanks to describe the SCO as an “anti-Western,” “anti-American,” “anti-NATO,” and “authoritarian” bloc, or even just an “ineffective talk shop.” While there is a hint of truth to each of these labels, they do not provide a clear picture. These labels reductively distort the SCO’s multi-layered nature as a platform and lead to misguided policies.

The problem arises from different conceptualizations of “security.” Western references to the SCO reduce security to a commonsensical notion of geopolitics as “hard,” or military power (hence, the NATO comparisons). The conception of security at the core of the SCO’s mission is much broader. Driven by China’s multi-faceted discourse on security, this conception subsumes not only hard geopolitical security but also geoeconomic development. The latter is a long-term strategy that might be called “security through development” that affects all SCO member states’ global and regional strategies.

In the past two decades, there has been no shortage of geoeconomic initiatives intersecting with the SCO, including China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC, driven by Iran, Russia, India, and Azerbaijan), and the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). The SCO is increasingly becoming a platform to facilitate the materialization of these initiatives.

More precisely, the SCO has evolved into a platform for sociality. There are two types of processes bonding SCO countries together: one is negative short-term bonding based on common geopolitical grievances (such as sanctions or NATO-related concerns) against the West, mainly the United States. This bonding is surface level and receives considerable media coverage in the West. Second, and more importantly, there is the long-term positive geoeconomic bonding that takes place through infrastructure initiatives. Infrastructure cements relations, both literally and metaphorically, between all SCO-affiliated actors, including member states, observer states, and dialogue partner states.

Unlike negative geopolitical bonding, geoeconomic bonding does not get enough (if any) media coverage. Nor does it define itself in reference to the West but to an overly romanticized conception of “Eurasia.” Terms such as “Eurasianism,” “continentalism,” or “Silk Roads” have been bandied around to describe this loose community. Such a community, needless to say, is always a work in progress. Geoeconomically, it works through the alignment of SCO-related states’ developmental visions and strategies with one another.

To begin, Chinese president Xi Jinping started his first trip since the pandemic with a visit to Kazakhstan, the country where he introduced the BRI as his main foreign policy initiative. This speaks to how indispensable Central Asia and Kazakhstan are to China’s worldview. In a thinly veiled warning to Russia (and possibly the West), Xi said that China will defend Kazakhstan’s “sovereignty and territorial integrity.” A major aim of the meeting was to further “synergize development strategies” between the two countries.

After leaving Kazakhstan, Xi went on to Samarkand, Uzbekistan, to join the SCO summit. During the summit, China signed agreements worth $15 billion with Uzbekistan and emphasized the two countries’ “shared future.” On September 14, the day before the summit, China signed a long-anticipated agreement for the construction of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railroad. After being dormant for a long time, the CKU has received new momentum thanks to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s desire to have alternative corridors.

When completed, the CKU could give China access to Europe—via Iran and Turkey or exclusively through the Turkish Middle Corridor and the Caspian Sea on to Europe. Thus China-European Union (EU) connectivity can be secured independently of the Russia-dominated Eurasian Land Bridge. China already has created one such corridor through Central Asia and Iran that leads to Turkey and Europe, the so-called “China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor.”

Just before the summit, China also started a three-month trial run for the China-Afghan Rail Corridor, which also passes through Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. According to the agreement, the corridor reduces the time it takes for the goods to go from China to Afghanistan from two months down to two weeks. Remarkably, this corridor bypasses Pakistan, China’s “all-weather friend,” again to avoid dependence. All these dynamics are brought under the umbrella of the BRI.

Overall, since 2013, the BRI has been the most significant geoeconomic force producing a sense of sociality among SCO-affiliated countries and beyond. In fact, all SCO member states (with the exception of India), all observer states (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia), and all dialogue partner states (such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Nepal, Cambodia, Egypt, Armenia, Sri Lanka, Armenia, and Azerbaijan) have enthusiastically endorsed the BRI and more or less aligned their developmental strategies with the BRI. The SCO serves as a platform that gives institutional reality to this loose sense of community.

Iran also made headlines by signing the SCO’s memorandum of obligations to officially start its full membership acceptance process. It is expected to become a full member state in 2023. Under the new president, Ebrahim Raisi, Iran has clearly pivoted to Eurasia. Central Asia is no stranger to Iran as the two sides share many historical, cultural, and linguistic affinities. The region is part of what Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, refers to, rather romantically, as “greater cultural Iran.”

In a September 16 op-ed for China’s CGTV, Iranian foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian celebrated the SCO as the manifestation of Asian regionalism, continentalism, and multilateralism. He went on to boast of Iran’s geographic location in the middle of the SCO’s “like-minded” countries—an obviously exaggerated term. He referred to Rudaki, the Persian poet of the nine century from Samarkand, to point to the cultural and historical affinities between the two countries.

Those affinities are slowly being cemented through transport infrastructure and trade. During this summit, Iran and Uzbekistan signed seventeen memorandums of understanding (MoUs) and agreements covering a host of issues such as energy, transit, sports, and science cooperation. Arguably the most important motivation for landlocked Uzbekistan and other Central Asian actors is to gain access to international waters via the Iranian port of Chabahar, which India (another SCO member) has been investing in and modernizing to overcome its own geoeconomic challenges.

India needs Chabahar to gain connectivity to the Eurasian landmass via Iran. Pakistan, another SCO member which does not exactly find India to be a “like-minded” partner, has denied the latter access to transit routes via its land. In his speech at the SCO meeting, Indian leader Modi implicitly criticized Pakistan for denying India “full transit rights,” which are necessary for resilient supply chains.

Global supply chains were disrupted thanks to Covid-19 and the Russo-Ukrainian War. In a March 18 article, I predicted that INSTC would become indispensable for Russia, Iran, and India. Isolated from Western geography, Russia would need this initiative to redirect its geoeconomic orientation towards the east and south. It did not take long for that prediction to come true.

When the initial fog of war settled in Ukraine, the three countries started rapidly revamping the INSTC, Russia being the most desperate. Their efforts have recently involved Azerbaijan, an SCO dialogue partner, as well. On September 9, Iran, Russia, and Azerbaijan held their first trilateral meeting to ink a joint declaration on the development of INSTC and announced their intention to construct the Rasht-Astara Railway in northern Iran, which still needs to be built for INSTC to become fully functional. The countries also announced their intention of linking INSTC to the port of Chabahar.

During the SCO summit, Vladimir Putin also announced that Russia will send delegations from eighty of its major companies and corporations to Iran for trade deals. There has been a flurry of bilateral trade visits and agreements between Iran and Russia since the Russo-Ukrainian War started.

Iran is also in the process of finalizing a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EAEU, which is Russia’s geoeconomic initiative to bring former Soviet satellite states into its orbit. Iran signed an interim FTA with the EAEU which has been extended until 2025. Given all the above processes, Iran’s vision is to become the SCO’s transit gateway.

Iran’s relations with Pakistan have also warmed in recent years, thanks in no small part to geoeconomic dynamics driven by Chinese investments. Pakistan and Iran are close strategic partners of China. The latter hopes the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) can connect to the Iranian, Turkish, and even European markets. The Islamabad-Tehran-Istanbul (ITI) railway, which became operational last December, should be understood in terms of deepening China-Pakistan-Iran connectivity.

Geoeconomics and Geopolitics

There is much more to be said about the SCO’s geoeconomics. The preceding was only a limited number of examples to show that the SCO cannot be reduced to geopolitics alone. The SCO is a platform where a geoeconomic project of sociality is unfolding. This project produces romanticized notions of the self, others, the region, and the continent; “Silk Roads” is increasingly becoming such an overly romanticized trope.

No comments:

Post a Comment