THERESA HITCHENS

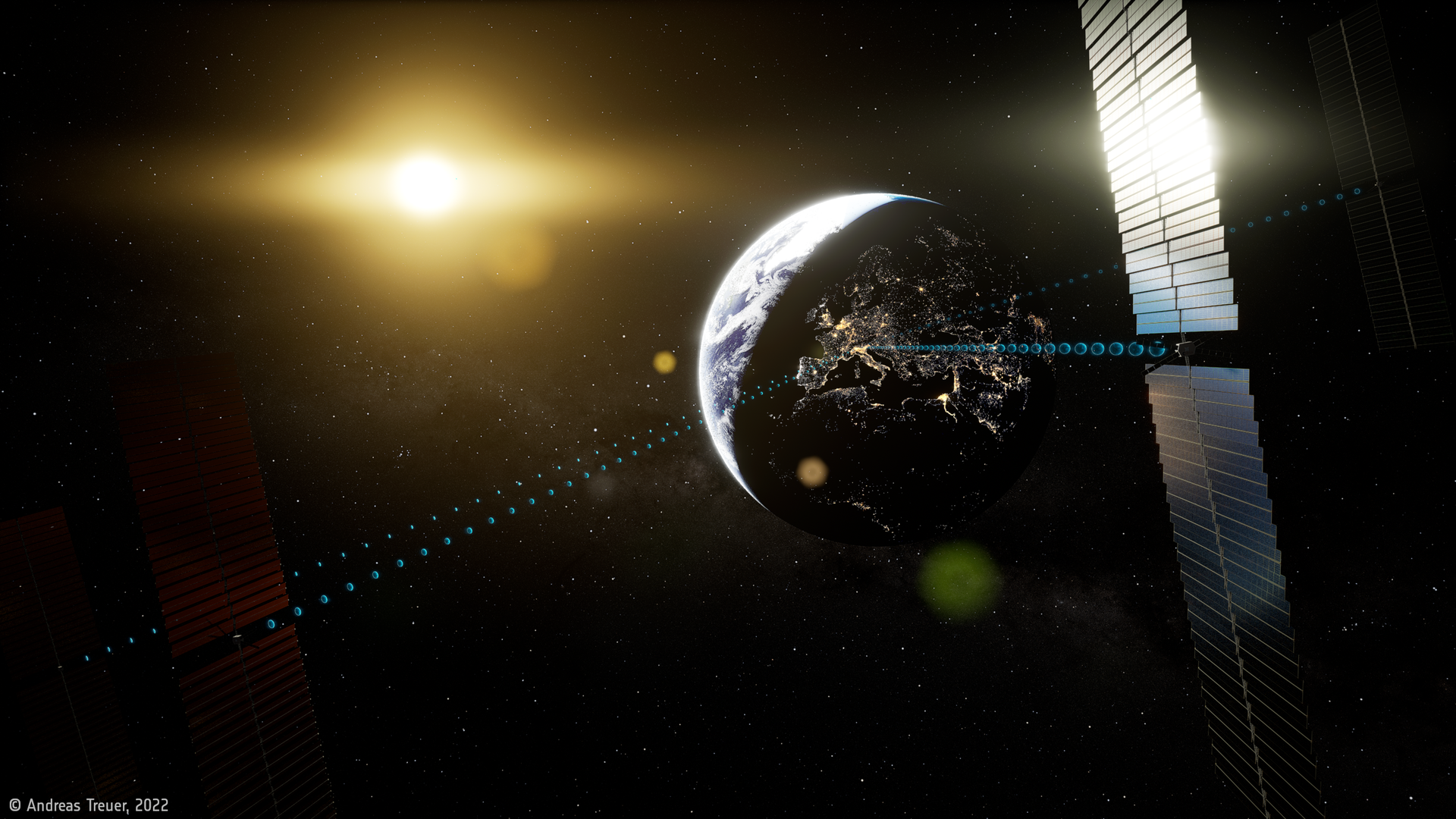

WASHINGTON — The idea of using satellites to capture solar radiation in space and beam it back to Earth to use as energy was first posited in 1968, and first caught the US government's interest during the mid/late-1970s “energy crisis.”

After a number of technology development initiatives by NASA and the Energy Department fizzled out due to technical and funding challenges, the Defense Department picked up the baton 40 years later. A 2007 report by the now defunct National Security Space Office dubbed space-based solar power a “strategic opportunity that could significantly advance U.S. and partner security, capability, and freedom of action.”

But ultimately Pentagon leaders at the time in essence tagged the issue as “not my problem,” and the report was filed away on a shelf somewhere deep in the five-sided building to molder.

Now, 15 years after the last failed push, the concept of solar power satellites seems to be back in fashion — not just in the US with initiatives at DoD and NASA, but around the globe — despite continued technical challenges involved in developing an operationally effective system, as well as lingering questions about the high investment costs of the supporting architecture.

Most recently, for example, the European Space Agency (ESA) in mid-August announced that it would be seeking funding from its decision-making ministerial council in November to launch a feasibility study program, called SOLARIS. In an Aug.16 YouTube video, ESA explained that the effort is part of the European push to find clean energy sources for the future that can help mitigate the climate crisis. If successful, SOLARIS would result in a fully-funded development program starting in 2025.

ESA hasn’t yet released its proposed budget for SOLARIS, with ESA officials currently engaging with representatives of member states to suss out their level of interest, an official at ESA’s European Space and Technology Research Centre in the Netherlands told Breaking Defense.

With the right tools to fill in gaps in data when it’s not available, or when the aircraft OEM is unwilling to participate, it’s possible to generate technical data packages that become the customer's property.

European and US officials with hands-on experience say up to now no European military has expressed interest in the concept. Instead, the continental focus is firmly on climate and future energy independence. The latter issue currently weighs the minds of leaders in European countries, like Germany, that are heavily dependent on Russian natural gas — as Moscow continues to throttle back exports to Ukraine’s supporters in the ongoing war.

However, in the United Kingdom, which is no longer a member of the European Union but continues to participate in ESA, there is support for the concept both from the UK Space Agency and the Ministry of Defence.

The UK Space Agency on Aug. 26 updated its July guidance document for a Space Based Solar Power Innovation Competition comprising a handful of planned projects worth up to £6 million ($6.9 million). And speaking July 14 at the Global Air and Space Chiefs’ Conference in London, MoD’s first-ever director of space operations waxed eloquent about the concept’s promise including for the armed forces.

In particular, Air Vice-Marshal Harv Smyth noted that China is now two years ahead of its own 2030 schedule for deploying an operational satellite designed to harness solar power — echoing concerns voiced by DoD supporters of space-based solar power that Beijing intends to dominate the future energy market.

According to a 2020 report by The Aerospace Corporation, China intends to become a “global leader” in developing solar power satellites, viewing their use as a “a strategic imperative to shift from fossil-based energy and foreign oil dependence.”

Japan, Russia and India also are pursuing development efforts but none as ambitious as that by Beijing, the reported noted.

In the past few years in the US, it is the military that re-invigorated government interest. After all, the US military has a huge financial stake in finding cheaper energy sources. DoD is the biggest single consumer of energy in the US, and the world’s single largest institutional consumer of petroleum, found a 2019 study by Brown University’s Watson Institute of International Public Affairs. Between 2001 and 2018, the military “has consistently consumed between 77 and 80 percent of all US government energy consumption,” the study said.

But for the moment, space-based solar power efforts in the US remain similarly small and confined to the realm of scientific study and demonstration — aimed at working out the myriad technical obstacles that remain in the path of developing an operational capability.

NASA in May announced that it is starting a study to review various approaches to power-beaming in space — for example, either microwaves or lasers can be used to transfer radio frequency energy converted from solar radiation on-board the satellite — to determine whether, and to what degree, the civil space agency should support new efforts. According to a May 28 report in Space News, NASA will compare space-based solar power to terrestrial alternatives and will examine the potential costs in the light of technological advances, such as lower launch costs.

Meanwhile, the Air Force Research Laboratory is gearing up for its next test under its ambitious Space Solar Power Incremental Demonstrations and Research (SSPIDR) initiative to develop a suite of foundational technologies.

Northrop Grumman is partnering with AFRL on SSPIDR, having put some $15 million of its own research funds into the project. The company also received slightly more than $100 million from AFRL in 2018 for the initiative’s flagship mission, an experimental satellite called Arachne due to launch in 2025.

The test, slated for late this month, is focused on the rectifying antennas, or rectennas, that are needed to convert electromagnetic energy to usable electricity on the ground, an AFRL spokesperson said.

AFRL and Northrop Grumman first “successfully demonstrated RF to rectenna wireless power beaming in early May 2022″ that was “an important step in validating the work that has been completed as SSPIDR progresses towards a fully functional space-based flight experiment,” said Paul Matthews, a Northrop Grumman fellow working on the project.

“A more complete demonstration will be performed in late September which will prove the ability to steer the RF beam and direct energy to multiple remote rectennas,” he added in an email.

Another SSPIDR sub-experiment, called SPIRRAL for the Space Power Infrared Regulation and Analysis of Lifetime, remains on track to launch in the summer of 2023. SPIRRAL will test “Variable Emissivity Materials, or VEMs onboard the International Space Station,” the AFRL spokesperson said. Such materials are needed to manage the intense heat from solar radiation bombarding the satellites systems.

No comments:

Post a Comment