Catrina Doxsee

Chairman Lynch, Ranking Member Grothman, and distinguished Members of the Subcommittee on National Security, thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Subcommittee on “Putin’s Proxies: Examining Russia’s Use of Private Military Companies.” As this testimony highlights, in recent years Russia has increasingly used private military companies (PMCs) such as the Wagner Group as a tool of irregular warfare to exploit instability around the world in pursuit of its own geopolitical, military, and economic goals.

Still, Russian PMCs have a mixed record of operational success, have engaged in human rights abuses, contributed to regional instability, and have plundered natural resources from fragile states. These actions have created opportunities for the United States and its partners to exploit Russian vulnerabilities, limit the spread of Russian influence, and hold PMCs accountable for illegal activities.

This testimony is divided into three sections. The first provides a brief overview of Russian PMCs, including the Wagner Group, and the tasks and objectives they most often pursue. The second provides examples of Wagner’s operations in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including their successes, failures, and the evolution of Russia’s PMC strategy across deployments. The third provides implications for the United States.

I. Russian Private Military Companies

PMCs linked to the Russian government regularly provide training and operational services in order to spread Moscow’s influence, expand its military and intelligence footprint, and to secure access to natural resources and other economic gains. As a study conducted for the U.S. Army’s Asymmetric Warfare Group concluded: “Russian PMCs are used as a force multiplier to achieve objectives for both government and Russia-aligned private interests while minimizing both political and military costs.”1

PMCs are appealing to Moscow based on their deniability, the lack of state accountability for their actions, perceived expendability in comparison to Russian forces, and lower costs.2 PMCs are technically illegal under Article 359 of the 1996 Russian Criminal Code, which states: “Recruitment, training, financing, or any other material provision of a mercenary, and also the use of him in an armed conflict or hostilities, shall be punishable by deprivation of liberty for a term of four to eight years.”3 Because of this, Russian PMCs are not legally registered organizations and do not pay taxes to the state—meaning that they are not recognized as a Russian entity and do not officially exist.4

Nonetheless, PMCs are closely linked to Russian oligarchs close to Putin, such as Wagner-owner Yevgeny Prigozhin, and most operate via unofficial links to the Russian government. This includes the Kremlin, Russian Ministry of Defense (particularly the Main Intelligence Directorate, or GRU), Federal Security Service (FSB), and Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). Wagner, for example, operates a training facility adjacent to the location of the 10th Special Mission Brigade of GRU Spetsnaz in Mol’kino, Russia. The satellite imagery that follows indicates the main base, including a headquarters, barracks, airborne training and obstacle courses, weapons and munitions storage, and other military facilities, as well as the six-acre Wagner facility located north of the main base. This Wagner base includes approximately nine permanent structures of varying sizes, and cargo trucks, small trucks, and civilian vehicles are present.5

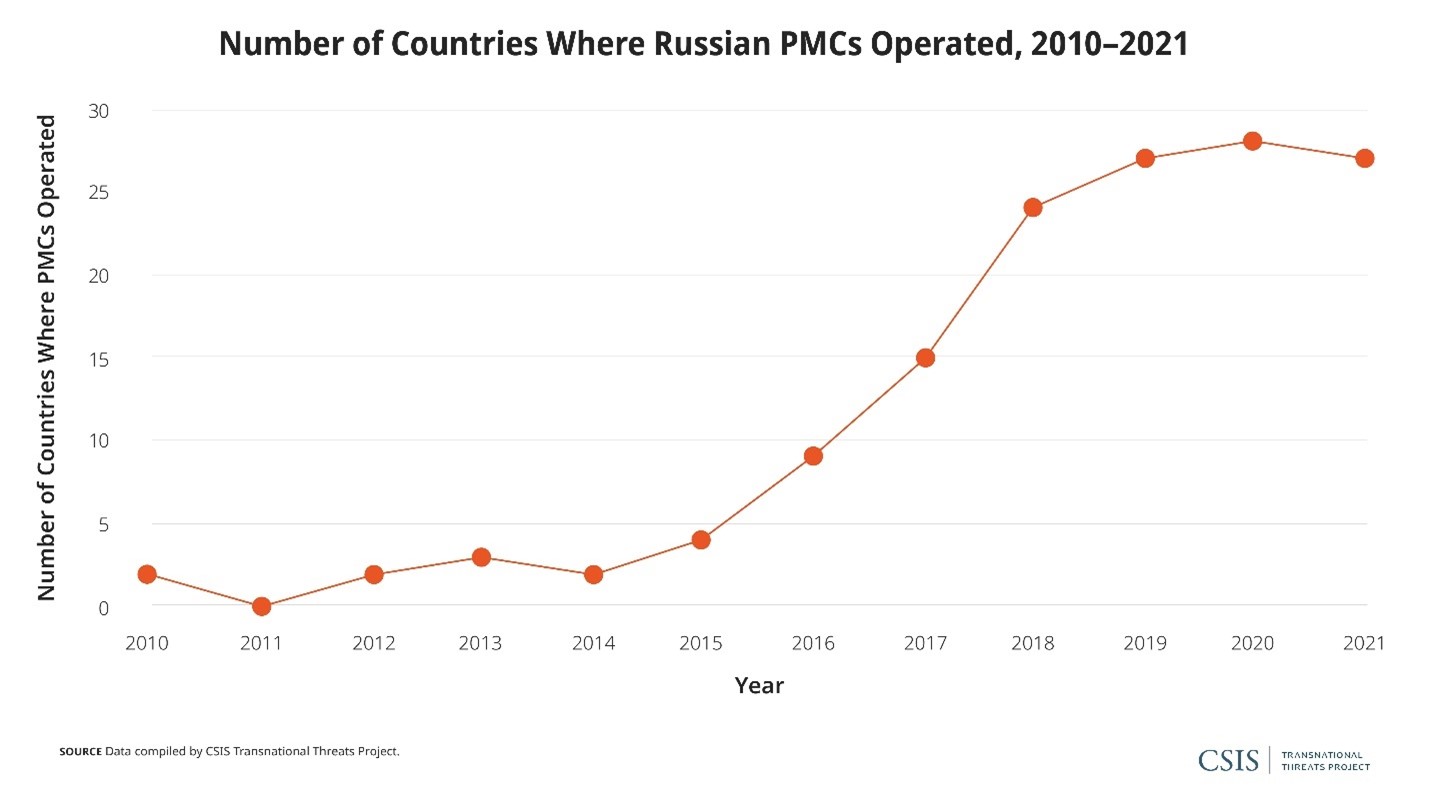

Russia has increased its use of PMCs as a tool of foreign policy and irregular warfare since approximately 2015. This growth was likely driven by Moscow’s desire to expand its influence after it annexed Crimea in 2014 and then started a war in eastern Ukraine, where PMCs played a key role.6 As the following figure highlights, the number of countries where PMCs operate around the globe increased sevenfold between 2015 and 2021, from 4 countries in 2015 to 27 in 2021. Russian PMCs are reportedly now active in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Asia, and Latin America—including in such countries as the Central African Republic (CAR), Libya, Sudan, Mali, Syria, Ukraine, and Venezuela. There is substantial variation in PMC organization, scale, roles, tasks, and funding arrangements across different deployments. Common tasks include training and equipping local forces, combat operations, site and personnel security, intelligence collection, and information operations.7

II. Wagner Group Activities in Sub-Saharan Africa

More than half of the countries in which Russian PMCs operated between 2016 and 2021 were in sub-Saharan Africa. In this region, Russia has targeted resource-rich countries with weak governance, including Sudan, the CAR, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Mali. In each of these countries Russia has exchanged military and security support for economic, geopolitical, and military gains. These include influence, basing rights, financial contracts, and access to natural resources, such as gold, gemstones, and energy reserves.8

PMC deployments in sub-Saharan Africa often fulfill the terms of or facilitate agreement to diplomatic and security cooperation deals with the Russian state. The scale and scope of PMC deployments—and the corresponding security cooperation goals—vary widely across locations. Some deployments are small, consisting of roughly 10 to 15 troops tasked with facilitating arms transfers and training local personnel to use Russian-supplied equipment. Others are larger, involve more significant benefits for the Russian state, and may to some extent be internationally recognized or approved. For example, Wagner began its activity in the CAR, which has been under a UN arms embargo since 2013, after the United Nations granted Russia a waiver to send trainers, weapons, and equipment to Bangui in December 2017.9

Moscow accelerated its efforts to forge cooperation agreements with sub-Saharan African countries with its first Russia-Africa Summit in Sochi in 2019. Preparations are currently underway for the second Russia-Africa Summit, which will be hosted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in Fall 2022. Moscow’s relationships in Africa have become more important since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions against Russia. Access to raw materials via mining concessions and other economic opportunities in partner states in Africa may allow Moscow to skirt sanctions. For example, Meroe Gold, a Wagner-linked shell company, runs gold mining operations in Sudan. Russia is reportedly smuggling gold out of Sudan to buoy the Kremlin’s $130 billion dollar gold supply and lessen the impact of Western sanctions.10

However, PMCs have achieved varying levels of success in different countries and with different types of missions. In most cases, Russian PMCs have been more concerned with achieving their own geopolitical goals and securing financial gain rather than resolving the security challenges they were deployed to address. This dynamic is exacerbated in cases in which a local, autocratic regime is more concerned with using Russian PMCs for its own preservation—referred to as “coup-proofing”—than for achieving security goals. The remainder of this section provides examples of Wagner deployments in sub-Saharan Africa that have been relatively successful, have experienced mixed success, or have failed.

One of Wagner’s most successful deployments is in the CAR, which has faced a decade of security challenges from armed rebel groups. Originally dispatched to facilitate arms transfers and to provide training and protective services, Wagner personnel have become an integral part of military operations to repel rebel groups. Wagner-linked companies have also established widespread mining operations as well as a steady stream of pro-Russia propaganda and disinformation to further Moscow’s interests and the longevity of their own deployment.11

However, this “success” has been predominantly on the part of Wagner and the Touadéra regime; the local population has suffered growing violence and human rights abuses at the hands of Wagner personnel. In a June 2021 report, UN Security Council investigators documented extensive violations of international humanitarian law by Russian PMCs in the CAR, including excessive use of force, the murder of civilians, rape, torture, occupation of schools, and widespread looting, including of humanitarian organizations.12 A similar pattern of human rights abuses has emerged in Mali, where Wagner deployed in December 2021.13

Other Wagner operations have resulted in more mixed success. Wagner personnel deployed to Madagascar, for example, to support and advise candidates in the 2018 presidential election, as well as to provide military training, security assistance, and information operations.14 Although Wagner initially intended to support incumbent president Hery Rajaonarimampianina’s reelection bid, they redirected their efforts among at least five candidates several times, none of which proceeded past early rounds of voting.15 The PMC analysts lacked sufficient background knowledge about Madagascar, and some had no prior experience conducting political field work.16 These operatives eventually supported the victor, Andry Rajoelina, in the later rounds of the election—more through process of elimination than strategy. In addition to political failures, PMC mining operations in Madagascar were met with worker strikes and public opposition. Still, Russian operatives successfully established a news platform through which to push propaganda and likely have benefited economically from revitalization projects in Toamasina.17

Finally, some Russian PMC deployments have failed outright. Roughly 200 Wagner troops arrived in Mozambique in September 2019 to provide equipment and combat support to counter the ongoing Islamist insurgency in the country’s northernmost province of Cabo Delgado, as well as propaganda and disinformation support, in exchange for access to liquified natural gas reserves and other natural resources, including diamonds.18 Wagner had little experience conducting counterinsurgency operations in the dense bush of northern Mozambique and difficulty coordinating with local forces, including because of language barriers and mutual mistrust.19 Following several failed joint offensives with local troops and significant casualties, Wagner troops retreated south in November 2019.20 Although additional Wagner troops arrived in early 2020 to support a new advance, it was too late.21 In April 2020, the Dyck Advisory Group—a South Africa–based PMC with more experience in the region—was hired to replace the Wagner Group.22

III. Implications for the United States

The spread of Russian PMC activity poses a moderate but concerning threat to U.S. interests and calls for a coordinated response. PMCs are one of many options in Moscow’s irregular warfare toolkit and should be considered alongside other Russian capabilities, as well as threats posed to the United States from states such as China, Iran, and North Korea; terrorist groups and other non-state actors; and transnational challenges, such as pandemics, climate change, and migration. The primary U.S. concerns related to Russian PMC operations include:Displacement of U.S. and partner presence and influence, including intelligence collection capabilities;

Spread of Russian military power projection and intelligence capabilities, as exhibited by efforts such as Moscow’s pursuit of a naval base with access to the Red Sea;

Destabilizing effects on local and regional security, which may allow terrorist organizations and other violent actors to expand their activities; and

Growing frequency of U.S. military and intelligence personnel encountering Russian PMC troops and operations in the field.

PMCs such as the Wagner Group have distinct weaknesses that the United States and its partners and allies are well-positioned to exploit. Opportunities to hold Wagner and other PMCs accountable include financial targeting, accountability under local and international law, transparency and information sharing, and offering viable alternatives for assistance.

Financial targeting: PMCs are profit-driven and rely on revenue for their existence—making them vulnerable to sanctions and other financial limitations. Moreover, Wagner’s relative monopoly over the Russian PMC market is a vulnerability. The United States, United Kingdom, and European Union have all sanctioned Prigozhin and others connected to Wagner operations, including due to their connections to the Internet Research Agency and interference in U.S. elections. This is a commendable step forward, and the expansion of a multilateral sanctions campaign against Russian PMCs would likely apply continued pressure to their ability to operate. However, Russian PMCs’ financial structures are intentionally complicated and opaque. Most rely on a series of financial facilitators, cut-outs, and front companies to mask their operations and origins.23 For instance, despite the inclusion of “group” in its name, the Wagner Group is best thought of as a loose, clandestine network of companies and financial intermediaries with links to Prigozhin and the Russian state. This structure complicates the efficacy of sanctions and other financial targeting, which PMCs can evade by shifting their operational structure and redirecting and obfuscating their financial activities. Therefore, expansion of sanctions would be most useful as one of several strategies to disrupt PMC operations.

Accountability under local and international law: PMCs lack government legal protections in foreign countries and they have engaged in illegal activities, including widespread human rights abuses. Without embassy protection, PMC contractors are susceptible to legal penalties, incarceration, and personal financial burdens. The United States and its partners should encourage the leaders of countries where PMCs are operating to take appropriate action against companies and their employees when they are engaged in illegal activities. International organizations such as the United Nations have played an important role in documenting the abuses committed by Wagner and other PMCs, and such efforts should continue.24

Transparency and information sharing: In addition to continuing to document human rights abuses and other malign activities linked to Russian PMCs, this information should be made widely available to the public and to nations that may wish to partner with PMCs, as well as information on PMCs’ previous failures. Through this information-sharing process, Western nations are well-positioned to focus their argument against Russian PMCs on transparency and local interests. Tensions with local societies have been common across PMC deployments, and prospective partners should know the true costs and risks of partnering with Moscow. For example, in the CAR, Wagner mercenaries have been regularly accused of crimes against the local population, including the rape of teenage girls in villages near PMC encampments.25 They also have been criticized for elevating the role of warlords and contributing to insecurity and human rights abuses.26 Local opinion articles have expressed frustration at Russians for treating the CAR as an economic opportunity to exploit without reciprocal development support or as a power piece in the competition between Russia and the West.27 Even a former member of the CAR government remarked, “In 2017, many thought that the Russians would do what France had not done: clean up the country. There was a lot of hope, but for the moment it is disappointment that dominates.”28

Offering viable alternatives: Many countries, particularly in Africa, viewed Russian PMCs as an appealing solution to security challenges because of their relatively low cost and easy availability. However, these PMCs prioritize their own interests and rarely seek to address underlying causes of violence and instability—and can in fact cause local violence to worsen. The United States and its allies are well-positioned to offer alternatives to Russian assistance through diplomacy, foreign aid, and long-term commitments to addressing root causes of instability while prioritizing needs identified by local partners.

The United States needs a coordinated strategy toward Russian PMCs that includes a wide range of diplomatic, intelligence, financial, military, and other actions. Unless disrupted, Moscow will likely continue to utilize PMCs as one of several tools to increase Russian influence and undermine U.S. and partner interests.29 The Russian government currently has little incentive to reduce its use of PMCs unless the United States and its partners increase the costs and risks.30 Russia uses PMCs such as Wagner to expand influence, build local partner capacity, and secure financial gains. Consequently, U.S. goals should be to raise the costs and risks of using PMCs so that Russia fails to significantly increase its influence, fails to strengthen local capacity, and fails to generate profits.31

No comments:

Post a Comment