Oliver Alexander

"Problems in pumping arose because of the sanctions imposed against our country and against a number of companies by Western states, including Germany and the UK. There are no other reasons that would lead to problems with pumping,"1

With this quote to Interfax, Russian Press Secretary Dimitry Peskov clarified that Russian natural gas to Europe won’t be turned back on until sanctions are lifted. Russia now faces the task of attempting to sell its massive natural gas reserves to other markets, China being the main player.

Standing between Russia and successfully selling a large amount of natural gas to China are two large and seemingly unsurmountable hurdles:

Russian Gas Pipeline Infrastructure

Russian Liquid Natural Gas Infrastructure

Natural gas cannot simply be transported as easily as oil, coal or other fossil fuels. There are two ways to move large amounts of natural gas. The first is through a network of gas pipelines. The second is by using a natural gas liquefaction plant to turn it into “Liquid Natural Gas” (LNG), which can then be transported on specially designed LNG carriers. Both of these require large amounts of complicated and expensive infrastructure to be in place.

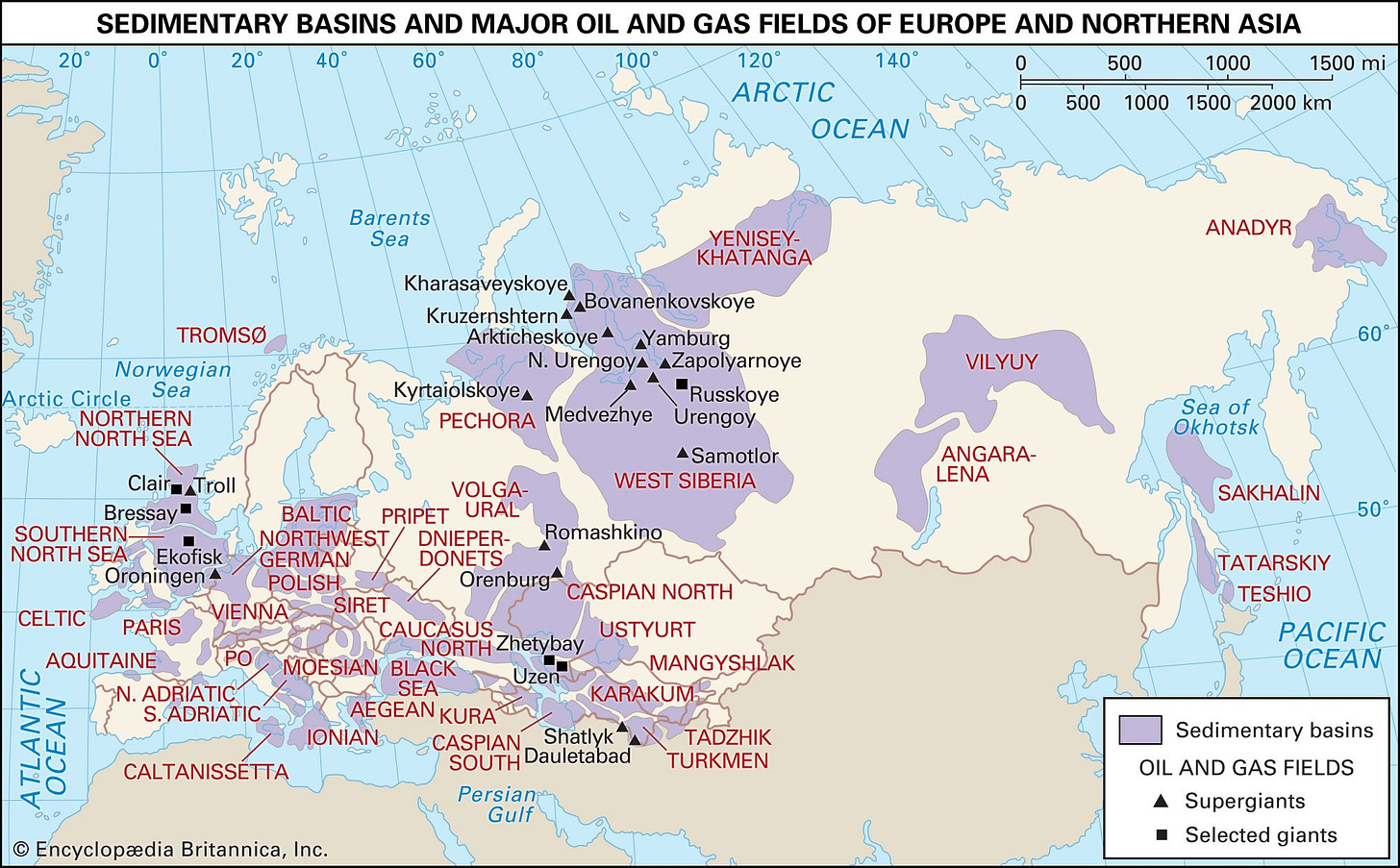

In order to make an accurate assessment of Russia’s ability to redirect gas flows form Europe to China, we must first look at the location of the major gas fields in Russia. As seen from the map below, most of Russia’s large gas fields are located in the West Siberian petroleum basin, the largest hydrocarbon basin in the world2. Russia’s two largest gas fields, the Urengoy and Yamburg fields, are located in the north of this area in the relatively remote Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. These two fields are the second and third largest natural gas fields in the world respectively, with only the South Pars/North Dome Gas-Condensate field in the Persian Gulf being larger.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

In the far east of Russia, the main gas field is the Chayanda gas field, located in the Republic of Sakha and is part of the Vilyuy basin. The Chayanda gas field is estimated to contain a total of approximately 1.24 trillion cubic meters of gas3. While large, this is 6.5 times smaller than the Yamburg gas field and 8 times smaller than the Urengoy gas field.

Russian Gas Pipelines

Current pipeline infrastructure in Russia reflects the concentration of natural gas fields in the northwest of the country compared to the far east. As Wood Mackenzie's map shows, most of Russia’s gas pipelines go from the Urengoy and Yamburg gas fields west to supply European nations. The only currently operational export gas pipeline of note in the East is the Power of Siberia pipeline, which transports gas from the previously mentioned Chayanda gas field to China.

The Nord Stream 1 pipeline alone supplied 59.2 billion cubic meters of natural gas to Europe in 20214. It is planned for the Power of Siberia pipeline to export 38 billion cubic meters of gas to China by 2030. Currently it is exporting around 10 bcm a year, though exports have increased to approximately 7.5 bcm for the first half of 2022.

On the September 7th, Russia agreed to a deal with China to begin the initial stages of the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, which will be able to supply China with 50 bcm annually from the Yamburg via the Yamal gas production center5. While this will assist Russia in becoming less reliant on Europe, this is a long term solution to a problem with very real short term consequences for Russia.

Construction of the original Power of Siberia pipeline was a decade long process that started with the approval of the Eastern Gas Program by the Russian Ministry of Industry and Energy in September 20076. Construction on the 2200km pipeline began in September 2014 and it was completed in December 2019, with construction taking just over 5 years.

The Power of Siberia 2 pipeline will be longer at 2800km and is currently scheduled to begin construction in 20247. The current completion date is in 2030, but as with many current Russian natural gas infrastructure projects, western sanctions may greatly impact the timeline, delaying the project further into the future.

The best case scenario for Russia is that they are able to export the same approximate volume as the Nord Stream 1 pipeline to China in 8 years through the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline. In the scenario where both the Power of Siberia and Power of Siberia 2 pipelines export natural gas to China at full planned capacity they will combined be able to export 88 billion cubic meters of natural gas to China per year. This is still only just over half of the 155 billion cubic meters of Russian natural gas that the European Union imported in 20218.

Russian Liquid Natural Gas Infrastructure

As the required pipeline infrastructure for Russia to transport gas from its largest Western gas fields does not exist at this time, and would require a decade or more to be constructed, they will need to make use of their liquid natural gas (LNG) terminals. Here Russia faces a different, but equally serious set of challenges that make the shifting the majority of the former European bound gas flows from the Western gas fields eastwards an impossibility.

At this time Russia has two main “Liquid Natural Gas” (LNG) terminals for the liquification of natural gas into tanker transportable LNG. These are the “Yamal LNG Terminal” and the “Sakhalin II LNG Terminal”

Yamal LNG Terminal

The Yamal LNG Terminal is located in Sabetta on the Yamal Peninsula in the far north of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. It consists of 4 separate “trains”, or liquefaction plants. There are 3 main “trains” each capable of producing 5.5 mmt per annum of LNG. A forth smaller “train” was launched in May 2021, capable of producing an additional 0.9 mmt per annum. The total annual output of the plant is 17.4 mmt of LNG9. This makes it the largest LNG liquefaction plant in world in terms of annual output.

Sakhalin II LNG Terminal

The Sakhalin II LNG Terminal is located on Sakhalin, Russia’s largest island, North of the Japanese archipelago. It consists of 2 “trains” each capable of producing around 5.4 mmt per annum of LNG for a total of 10.8 mmt per annum10. A third train was planned with an additional capacity of 5 mmt per annum, but this has currently been set on hold indefinitely11.

On top of these two main LNG liquification terminals, Russia has two smaller terminals, the “Vysotsk LNG Terminal” and the “Portovaya LNG Terminal”.

Vysotsk LNG Terminal

The Vysotsk LNG Terminal is located about 100 km northwest of St. Petersburg in Russia’s Leningrad Oblast. It is a small gas liquefaction plant that is only able to produce 0.66 mmt per annum12. It was originally planned that it would receive a second "train" in 2020 capable of increasing production by an additional 1.1 mmt per annum. Since 2020 there has been no update on this second "train" and no indications that initial stages of any construction have begun. It is therefore considered to be on hold indefinitely.

Portovaya LNG Terminal

The Portovaya LNG Terminal is Russia’s newest LNG terminal. It is located about 30km west of the Vysotsk LNG Terminal. The liquefaction plant was originally meant to be operational in 2019, but was delayed several times. It finally became operational on September 6th 202213. The plant is able to produce a total of 1.5 mmt per annum. Portovaya LNG Terminal is connected to and fed by the Portovaya compression station that also feeds the Nord Stream pipeline14. Due to this, prior to becoming operational, the terminal could be seen flaring excess gas on satellite imagery from June 14th onwards, after Russia reduced gas flow in the Nord Steam 1 pipeline to around 40%.

Copernicus imagery of Portovaya LNG Terminal from June 13th to 28th shows flaring starting at the same time as Nord Stream gas deliveries were cut to 40% on June 14th

Finally Russia has been in the process of constructing the “Arctic LNG 2 Terminal, which would become the world’s largest LNG liquefaction plant with an annual output at completion of 19.8 mmt of LNG.

Arctic LNG 2 Terminal

The planned “Arctic LNG 2 Terminal” site is about 70km east of Sabetta, on the Gydan Peninsula15. The terminal was initially planned to have 3 “trains”, each capable of producing 6.6 mmt per annum of LNG. Due to sanctions stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, construction on two of these “trains” has been halted indefinitely after Chinese yards working on modules for them were ordered to stop work16. The first "train" was scheduled to begin production in 2023, but sanction related issues have pushed this to at least 2024.

Combined, Russia’s current LNG liquefaction plants have the capacity of producing 30.36 mmt per annum of liquid natural gas. The conversion from million tonnes of LNG to billions of cubic meters of gas in its gaseous form is 1 million tonnes of LNG to 1.379 billion cubic meters of gas17. As such, the current annual Russian LNG capacity is the equivalent of 41.87 bcm of gas. Of this, 26.97 bcm (19.56 million tonnes of LNG) comes from Russia's western gas fields, previously supplying Europe with gas.

Russia’s western LNG liquefaction plants are only able to produce the LNG equivalent of 45.46% of the Nord Stream 1’s 59.2 bcm of gas flow in 2021. Even in optimal conditions, Russia does not have the LNG infrastructure to come close to shifting Nord Stream 1's former gas flow eastwards.

The Yamal LNG Terminal’s geographic location inside of the arctic circle is not ideal for the export of LNG to China and Asia. In previous years during the winter, the ice becomes too thick for normal shipping in the Northern Sea Route. This has meant that Russia has been forced to use the Fluxys terminal at Zeebrugge, Belgium to ship LNG from Yamal to Asia. This made the Yamal LNG Terminal very reliant on Europe for the exporting of LNG.

To combat this reliance Europe, Russia has commissioned 15 new ARC7 icebreaking LNG carriers. These new ACR7 carriers are able to break through up to 2.1m of sea ice, which opens up the use of the Northern Sea Route year round for exports to Asia directly from the Yamal LNG Terminal18. Each of these LNG carriers is able to transport approximately 170,000 cubic meters of LNG19, the equivalent of 68,850 tonnes of LNG20, meaning around 256 yearly trips are needed to export the terminal's full annual production.

Unfortunately for Russia’s goals of non-reliance on Europe for LNG exports, the ARC7 LNG carriers, as with many icebreakers, use ABB Azipods for propulsion21. This jeopardises the entire ARC7 fleet of potential future western sanctions on the export of parts and maintenance equipment for these Azipods. In that case, the export of LNG from the Yamal LNG Terminal will once again become heavily limited in the months where sea ice renders the Northern Sea Route unpassable to normal shipping.

An argument has been made by people, that Russia is or will simply re-export sanctioned LNG through China to Europe at inflated prices. Even if this was the case, Russia’s current LNG exports to China are miniscule compared to Europe’s current LNG imports. In the first half of 2022 China imported a total of 2.35 million tonnes of Russian LNG22. The European Union and United Kingdom averaged an import of 14.9 billion square feet of natural gas a day through LNG terminals. One million tonnes of LNG23. One million tonnes of LNG becomes 48 billion cubic feet of gas after regasification24. This means that the China's total imports of Russian LNG would only equal 7.5 days or 4.1% of Europe's LNG imports in the first half of 2022. Even if China was re-exporting the entirety of their Russian LNG imports to Europe at inflated prices, it would be a drop in the ocean of LNG that Europe is importing from other sources.

In summary, the majority of Russian natural gas infrastructure was developed with the intention of supplying gas to Europe through pipelines. Due to this most of Russia’s pipeline infrastructure and capacity is directed at Europe. This also means that there is currently no pipeline infrastructure in place to move gas from Russia’s western gas fields to China. Plans to remedy this will take the best part of a decade in the best case scenario and will only allow the export of approximately 33% Russia’s current European exports to China. Western sanctions may further hampered by limiting the exports of pipeline critical components to Russia.

In regards to liquid natural gas, Russia faces a similar series of issues. Current LNG infrastructure is not sufficient to reroute a significant proportion of the former European flows to China. Furthermore, western sanctions have effectively killed many of Russia’s short/mid term plans for the expansion of its LNG production capacity. At the same time, Russia’s attempts to get away from a reliance on the Europe has potentially backfired with their new fleet of ARC7 LNG carriers being reliant on critical spare parts from western manufacturers.

To answer the initial question of “Can Russia Shift Natural Gas Exports to China?”

No, not in a way that will make up the enormous deficit caused by stopping gas flows to Europe. To redirect the focus of their natural gas infrastructure will take Russia decades, cost hundreds of billions and may not even be possible depending on western sanctions on critical components.

No comments:

Post a Comment