Shuli Ren

China’s industrial policy seems to have fans across the Pacific. The US’s $280 billion Chips and Science Act is a direct response from the Biden administration to Beijing’s spending to help key industries. But just as the likes of Intel Corp. and Micron Technology Inc. jostle for a slice of US government support, the perils of relying upon public money are sending shock waves through China’s chip industry.

In recent days, corruption investigations have engulfed top officials in a sector that is integral to President Xi Jinping’s “Made in China 2025” ambitions. At least three senior executives from a $20 billion state-owned private equity fund, set up in 2014 to invest mainly in chip manufacturing, were detained; so was Xiao Yaqing, the head of the agency in charge of the nation’s industrial policy and the most senior sitting cabinet official ensnared in a disciplinary probe in almost four years.

It’s intriguing that the anti-corruption agency is looking into a top venture capital fund that has yielded substantial results. Phase 1 of the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund raised billions from the Ministry of Finance and China Development Bank Capital. Between 2014 and 2019, the so-called Big Fund invested in 23 chip companies, churning out one national champion after another. It backed Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., whose advanced chipmaking abilities may put it ahead of its US peers. It also seeded Tsinghua Unigroup Co. subsidiary Yangtze Memory Technologies Co., China’s best bet in NAND flash memory manufacturing.

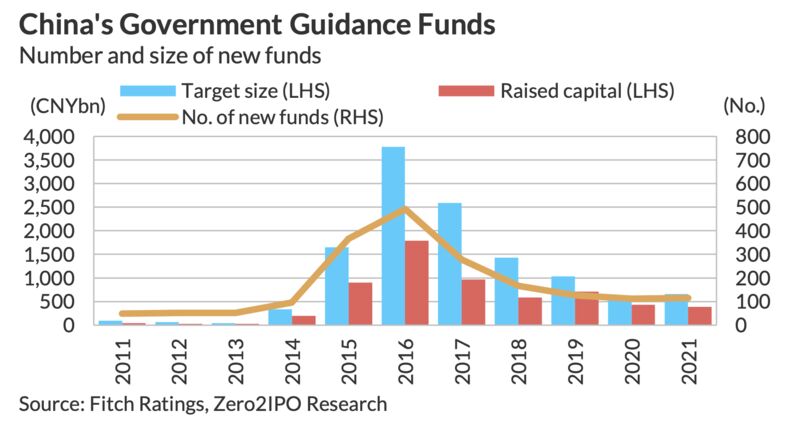

Does this mean the state-run venture capital model, which flourished during Xi’s reign, no longer works? Government-owned venture capital funds raised about 6.2 trillion yuan ($920 billion), almost all in the eight years through 2021. These funds have emerged as a key funding source for private companies, contributing about 10% of total capital raised last year.

Bloomberg

The Big Fund and thousands of so-called government guidance funds are designed to mimic venture capital. The ultimate investors — for instance, the Ministry of Finance in the case of the Big Fund — are not involved in daily fund operations or investment decisions. And the funds themselves are largely passive stakeholders in the companies they seed.

The Big Fund’s involvement in the flash memory maker YMTC is a good example. It contributed 49% of the initial capital, much more than the 13% from parent Unigroup. But it didn’t control YMTC.

This model was intended to encourage best practices in corporate governance. After all, what do bureaucrats know about running companies? However, with government investment — and the prestige that comes with it — the portfolio companies can easily go haywire. That guidance fund’s prestige opens doors to loans but can lead to excessive borrowing.

Big Fund’s entanglement with Unigroup ended in tears. At its peak, Unigroup’s empire had close to 300 billion yuan in assets and 286 consolidated subsidiaries. But it also touted a net debt-to-equity ratio of 125%, defaulted in 2020 and then went into a bankruptcy restructuring. Its long-time chairman Zhao Weiguo was detained in mid-July, possibly for investigations into related-party transactions, reported financial media outlet Caixin.

Guidance funds are known for the use of their reputation as leverage. An initial contribution from the government - often seen as a stamp of approval - can attract many multiples of the sum from other investors, the thinking goes.

Gavekal Research gave a good example: the massive Yangtze River Industry Fund that Hubei province established in 2015. The provincial government initially injected 40 billion yuan into the parent fund, with the aim of raising 200 billion for a group of sub-funds. These sub-funds, in turn, aspired to catalyze 1 trillion yuan of additional capital, the equivalent of almost one-third of Hubei’s annual economic output.

But who are the co-investors? A sizeable chunk came from banks’ wealth-management products, a form of shadow financing. Local governments’ financing vehicles, which are largely shell companies funded by loans, are big participants, too.

In other words, these state-sponsored venture capital funds enabled China’s already indebted corporates to borrow even more. Guidance funds’ investments, including those in strategic emerging sectors, are expected to slow this year, according to Fitch Ratings.

Upon the passage of the Chips act, there’s still nagging debate as to whether the US government is doing enough. The legislation includes $52 billion of grants to support advanced chip manufacturing as well as research and development in the US. That’s not much for cutting-edge manufacturing plants that cost more than $10 billion to build. And its scale matches only the Big Fund and its co-investors, which collectively expanded China’s chip manufacturing capacity by $70 billion in the five years between 2014 and 2019. There were thousands of other Chinese guidance funds out there, propping up nascent industrial technology firms.

No comments:

Post a Comment