Julian Spencer-Churchill Liu Zongzo

Domestic resistance to Chinese president Xi Jinping is currently manifesting in a wave of sensitive data leaks from within China. This is decisive for two reasons. First, it reveals a sharp value divergence between the policies and practices of the Communist Chinese regime and the rapidly changing political culture of the Chinese people. If this critical vulnerability is escalated by agents within or outside of China, it could lead to a crisis of legitimacy in Beijing. Second, these data leaks reveal China’s asymmetric susceptibility to cyber warfare. Beijing’s hyper-sensitivity to attacks on its legitimacy, both historically and with the current government, provide a powerful retaliatory instrument against hybrid Chinese aggression and China’s cyber espionage and public diplomacy campaigns.

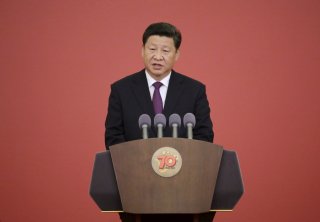

A recent spate of classified file leaks from China is a strong indicator that there is a factional struggle in the lead-up to the crucial 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that will determine whether President Xi Jinping will secure an indefinite appointment as General Secretary. Xi Jinping, whose support base is narrow within the party but benefits from strong popular support, faces those targeted by his successive anti-corruption campaigns, including the business-oriented Shanghai Gang of Jiang Zemin. For example, Jiang Zemin’s grandson, Jiang Zhicheng (Alvin Jiang), and Jack Ma’s relationship can be traced back to 2012 given Alibaba’s close affiliation with the Jiang faction. In April 2022, a book entitled China Duel, authored by a princeling with the pseudonym Yang Xiang, revealed extensive details on the Jiang faction’s attempt to have Xi demoted and dismissed at the end of Hu Jintao’s tenure in 2012.

In early 2022, well-connected British journalist John Sudworth, who has nearly ten years of experience reporting from mainland China, obtained highly classified documents known as the Xinjiang Police Files from a database containing more than five thousand photographs of Uighur detainees from between January and July 2018. Although some allege the files were hacked by an external actor, the prevailing evidence suggests that it was released from within a government agency, possibly the Ministry of State Police (MSP). The release of these files was likely intended to intensify foreign and domestic indignation against Beijing for its human rights abuses and undermine government claims about their benign social engineering practices.

In June 2022, an audio recording of the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee’s War Transition Mobilization Meeting from May 14, 2022, was leaked to a well-known independent human rights journalist Jennifer Zeng. The file covers mundane policy issues but it exposes a serious lack of security that could only come about by deep political divisions within the CCP. Zeng holds a large follower base on social media and is believed to not have any contact or formal connections to high-ranking military officials. The most likely explanation for her to have obtained such a clandestine recording is by someone motivated to undermine Xi Jinping’s apparent intent to choreograph a victorious Taiwan crisis as a historical achievement to cement his rule.

Most recently, in July 2022, a twenty-three terabyte JSON database file was offered for sale for ten Bitcoins (the equivalent of approximately $200,000), containing the detailed personal information, personal addresses, criminal offenses, and judicial records of 970 million Chinese citizens. According to the founder of the threat intelligence firm Shadowbyte, Vinny Troia, the data was made available for more than a year before being withdrawn for unknown reasons. On July 3, 2022, the executives and senior technicians of Alibaba, through whose servers the data would have been removed, were summoned by Shanghai police. Unlike regular JSON database files, the type of special Chinese characters used indicates that these files were tailored for internal use. The file may have been intended to be used for database searches through ES (Elasticsearch Service).

The most likely explanation is that someone with access to the files of the Ministry of State Police, decrypted, merged, and then deliberately placed the file for public discovery on an open server. What is interesting is that the data had enormous potential for blackmail but was not wielded for this purpose; its sale value was far below an extortionate market value. The price tag seems to have been a means of garnering attention for the leak rather than to secure proceeds since collecting such a small ransom would hardly justify the risk. The release of private information of Chinese citizens was also meant to trigger outrage among the wider population, exposing government intrusiveness and data security incompetence. The timing of this leak suggests, once again, that it was intended to humiliate Xi Jinping during the politically sensitive commemoration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Hong Kong’s administrative transition.

The modality of these leaks reveals an uncoordinated political, rather than criminal, motive to embarrass Xi. The unprecedented pace, sensitivity, and risks involved in releasing the leaks suggest that there is profound resentment within the CCP bureaucracy. As the 20th Party Congress moves closer to its November 2022 commencement, more leaks are expected. The cohort most damaged by Xi’s anti-corruption campaign are middle-ranked and regional officials, whose own power arrangements have been damaged by Xi’s assertion of central influence in the provinces. Anticipating a perpetuation of reforms by Xi, these bureaucrats have found common cause with the Jiang faction, in what can be described as a reputational scorched earth struggle (玉石俱焚). Xi’s principal weakness is that given Beijing’s poor tax collection practices, the provinces have been left to their own devices to raise capital, and are thus financially independent and have an incentive to remain so.

It is not at all certain that Xi will be granted indefinite tenure and what it will cost in concessions to other factions and newly empowered influence brokers. Xi is sensitive to the widespread recognition in China that leaders are most likely to be deposed when failing to address ecological crises, which are emerging with increasing frequency in an age of climate change. It is unclear whether the draconian methods used to eradicate the current Covid-19 variants have yielded a net legitimating benefit to the regime. China, a net importer of food, is persistently vulnerable to supply shocks and inflation caused by the Russo-Ukrainian War. China’s labor force began its contraction in 2012 and China’s total population is expected to begin shrinking in 2025, despite generous three-child family policies. Beijing is also facing an energy shortage and hazardous oil dependence on suppliers like Venezuela. Rising inflation, overvalued real estate, the erosion of public confidence in the security of deposits in China’s banking system, and a decline in foreign investment are creating an unprecedented challenge to Xi’s goal of stability. These leaks are a public demonstration that Xi is incapable of maintaining the image of a cohesive society in China.

Senior communist officials view the reliability and support of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as key to maintaining their positions of power in times of crisis and transition. During the June 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, Deng Xiaoping doubted the loyalty of the local Beijing PLA commander, Gen. Xu Qinxian, and he instead mobilized the 12th Army from the Nanjing military district, along with eight other armies from three other military districts, to intervene. Xi has actively promoted loyalists within the PLA and granted considerable foreign policy influence to the military, particularly over Taiwan, in exchange for their support, as the June 13 announcement of a law pertaining to military operations other than war indicated. However, coup attempts are rare in China and military support is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition to remain in power. In August 1971, Chinese Army Marshal Lin Biao attempted a coup against Chairman Mao Zedong and died in flight with his family.

These security breaches should remind foreign policymakers that Beijing’s principal vulnerability is not its dependence on energy, food, or investment. During a crisis, the nationalist Chinese population may well accept short-term deprivation for long-term security and stability. Rather, it is the persistently clumsy handling of modernization by the Communist Party, despite the legitimacy won by fostering unprecedented economic growth. That China spends as much on domestic security as it does on its military signals this weakness. Exploiting this social fracture is complex, however, as any perceived Western involvement will almost immediately trigger popular support for the Communist Party among nationalist elements of society, including the military. Instead, fostering a climate of constant political scandal in China may prove to be a decisive contributing factor if it undermines the widely held myth of the CCP’s infallibility.

No comments:

Post a Comment