Christopher Carothers Huan Gao

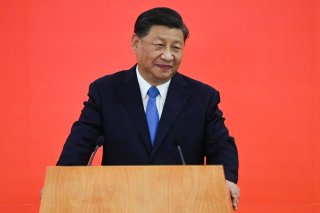

For decades, capable management of the economy and policies that promote strong growth have been the cornerstones of the Chinese Communist Party’s strategy to maintain social and political stability. But President Xi Jinping’s policy decisions, especially since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, show that this era is likely over.

Slaughtering one sacred cow after another, Xi has destroyed profitable industries with a word, shut down major cities for months at a time, and sought to cut China off from international markets. Analysts have often portrayed these moves as blunders that open Xi up to challenges from within the party. Yet it is time to embrace the reality that Xi prefers it this way. His vision for maintaining stability calls for extreme political and ideological control, and he is more than willing to sacrifice economic progress to achieve it.

Last year, the party leadership surprised observers by launching a sprawling regulatory crackdown on China’s tech sector, real estate, cryptocurrencies, the private tutoring industry, and much more. The silencing of billionaire Jack Ma and investigations against his company, Ant Group, was just the first salvo in a clampdown on tech giants that has cost investors over $1 trillion and left the industry stagnant. A blizzard of fines, purges, and regulations has led to a funding crunch in the property sector, dragging down overall growth numbers. Harsh and unexpected decrees preventing tutoring companies from pursuing profits, going public, or raising foreign capital wiped out much of the value of leading companies and created an “existential crisis” for the entire industry.

Yet the single costliest choice has been Xi’s insistence on adherence to a “zero-Covid” policy, now termed “dynamic zero-Covid.” As the rest of the world has opened up and accepted some level of coexistence with the virus, China has held out. This has meant imposing long lockdowns in dozens of cities—Shanghai being the most prominent example. Businesses have failed at unprecedented rates across the country, especially small and medium-sized ones. Moreover, zero-Covid has shut China’s doors to the outside world, which is often portrayed in state media as a dangerous source of infection. Xi has sent clear signals that there will be no retreat from zero-Covid, especially not before the Twentieth Party Congress later this year.

“Even if there are some temporary impacts on the economy, we will not put people's lives and health in harm’s way,” Xi Jinping said in June.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, Xi’s “no limits” partnership with Russia and soft support for Russia’s actions have created additional economic risks. As Russia’s economy is being pummeled by international sanctions, Xi’s policy opens Chinese firms up to secondary sanctions and other uncertainties. Nor is it clear that closer trade relations with Russia can compensate for losses. China’s position on the Russo-Ukrainian War has also strained relations with Brussels, stalling negotiations on the long-awaited EU-China Comprehensive Investment Agreement. In addition, China has levied sanctions against European, American, and other foreign companies and individuals in recent years, often in response to criticism over its policies toward Hong Kong or Xinjiang.

The collective economic cost of Xi’s policies has been substantial, including reduced industrial output, severe capital flight, and unemployment rates that in the past would have been a five-alarm fire, especially in the key urban youth demographic. Surveys of economists suggest that China’s growth will slow to around 4 percent this year, missing its 5.5 percent target.

But Think of the Children!

Xi’s detrimental economic policies extend far beyond misguided attempts to correct real estate bubbles or local governments’ overinvestment in infrastructure; they decimate prospering industries in the name of social goals.

The starkest example of this is the July 2021 national policy aimed at reducing the workload of K-12 students. Under the banner of protecting children, the policy permanently ends supplementary educational services for K-12 students, effective immediately; no new business permits will be issued, and existing services must be converted to non-profit organizations.

Private education and training had been a booming industry, with total revenue in 2020 estimated to exceed $30 billion. As late as the second quarter of 2021, with the additional demand created by the pandemic, companies boasted the fastest-growing number of job openings.

The impact of Xi’s new policy was immediate and severe. New Oriental Education & Technology, a flagship education service company, reduced its number of learning centers from 1,669 in May 2021 to 744 by May 2022 and saw a 51.6 percent drop in revenue across the same period. New Oriental has been able to adapt somewhat, such as by expanding education services for adults, but numerous smaller companies have simply gone under and are now feeding China’s unemployment pool.

Yet, as critics have noted, this crackdown does nothing to solve the underlying economic and societal pressures that drive so many Chinese parents to sign their children up for round-the-clock tutoring in the first place.

Another industry suppressed supposedly for the sake of the kids is gaming. China has the world’s largest gaming market and the most developed esports market. China’s gaming industry generated $45.5 billion in domestic revenue in 2021 and the total export revenue was $17.3 billion.

The 2021 policy document, China Children’s Development Outline, limited gaming time for those under the age of eighteen, and strong enforcement mechanisms were imposed on all licensed games in China. The policy was built on past moves by Xi to eliminate violent, pornographic, or otherwise immoral content in video games that have rattled the industry since 2017. Its announcement led to a sharp and immediate drop in gaming companies’ stocks.

In addition to draconian regulations, there are also arbitrary interruptions. The government has been severely restricting the number of game licenses it grants, and between July 2021 and April 2022 it approved none. This regulatory uncertainty has devastated the industry; between July 2021 and July 2022, China lost 14,000 gaming companies.

Politics in Command

Why has Xi led so many policies that directly harm China’s economy? Analysts have often portrayed Xi’s moves as misguided attempts to avoid larger economic ills. Xi’s crackdowns on the technology and real estate sectors aimed to prevent bubbles and rebalance the economy. Zero-Covid is an attempt to protect the country’s weak healthcare system from going overboard. New rules on the education and gaming industries are investments in the health of China’s future workers.

Yet these explanations miss the big picture. Economically costly policies have all served to enhance the regime’s political and ideological control, both over the economy and over society.

Crackdowns on tech giants are driven less by distaste for monopolies, as in the United States, and more by fears that these companies are “insufficiently committed to promoting the goal advanced by the Chinese Communist Party,” as Harvard researcher Josh Freedman found. Similarly, restrictions on real estate borrowing and cryptocurrencies reflect fears that private market forces are too powerful, and that the state is losing its leading role in the economy and its free hand to dictate policy.

Zero-Covid has given Xi a perfect excuse to increase the government’s direct control over how Chinese people live, work, and travel. This control has been aided by the rollout of new forms of digital surveillance, such as the health code apps that citizens are required to download.

Clamping down on private education gives the party more complete control over what young people are learning, which is a key vector for propaganda. Over the past year, “Xi Jinping Thought” has been integrated into the national curriculum at all levels, including elementary schools.

Some of Xi’s mission of greater control is motivated by fears of foreign—meaning Western—influence in China. This is by no means a new concern but there has been a distinct rise in nationalism and xenophobia in China since the Covid-19 pandemic began, fanned in part by state media. Many of Xi’s economic crackdowns have a cultural decoupling effect, including preventing companies from raising foreign capital, making it difficult for foreigners to enter and stay in China, and increasingly discouraging Chinese students from studying abroad.

Xi’s desire to increase political and ideological control has accelerated over the last two years but such control has been a central goal since he came to power in 2012. Early on, critics noted that Xi’s sweeping anti-corruption campaign, the rollback of partial freedoms for civil society in person and on the internet, and China’s increasingly assertive actions on the world stage would have economic repercussions. That Xi has willingly borne those costs and is now going even further is evidence enough that for the first time since Reform and Opening, the party leadership is abandoning Deng Xiaoping’s old adage of “get rich first.”

That said, Xi’s program is no return to the Mao Zedong era. Xi’s authoritarianism has inspired many comparisons to Mao’s but both the party and China have changed immeasurably over the last half-century. What Xi aims to do is draw on general ideas and practices from the Mao era—the importance of ideology, propaganda, and putting politics in command of the economy—and adapt them to a new era.

No comments:

Post a Comment