Gil Barndollar

One year after the stunningly swift collapse of its government and the return of the Taliban, Afghanistan has faded to the edge of world attention. Despite a crippled economy, massive food insecurity, an earthquake, and an ongoing insurgency by the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISIS-K), the West isn’t interested. With only slightly less speed than the Taliban’s 2021 return to power, Afghanistan has plummeted down the list of Western security concerns.

The United States entered Afghanistan to disrupt and decimate Al Qaeda, and to teach its Taliban backers a lesson. Despite an intermittent, unserious, and wholly quixotic attempt to apply flawed Western counterinsurgency doctrine to Afghanistan, counterterrorism was always the overriding U.S. interest in the country. As maximalist U.S. aims of a united, democratic, peaceful Afghanistan slowly proved unattainable, it was counterterrorism—really, the fear of a successful attack on U.S. soil under the watch of a president who had had the resolve to order a final withdrawal—that kept an American military presence in Afghanistan.

When President Joe Biden finally summoned that resolve and withdrew the remaining U.S. troops, the ensuing implosion of the Afghan government removed a final hedge against terrorists: the ability to both gather intelligence and attack potential transnational terrorists through Afghan proxies.

The CIA’s “Zero Units,” direct action Afghan commando units funded and run by agency officers, had provided both a highly effective means to harry and attrit Al Qaeda and a platform for intelligence collection throughout some of the most violent and insecure corners of the country. The Zero Units were also one of the bright spots of the Afghanistan evacuation last August. The CIA, according to the Washington Post’s David Ignatius, managed to evacuate more than 20,000 of its Afghan partners and their families.

Both before and after the withdrawal, the Biden administration promised to contain terrorism through “over-the-horizon” capabilities, primarily strikes by armed drones flying out of bases over a thousand miles from Afghanistan. Critics dismissed this as an empty promise; “fictitious,” even. Former U.S. Central Command head Gen. Kenneth McKenzie stated in December that the United States now had “about 1 or 2 percent of the capabilities” it previously had to surveil Afghanistan. Intelligence officials warned of Al Qaeda or the Islamic State reconstituting themselves in an Afghan safe haven and being able to strike beyond Afghanistan’s borders in as little as six months.

Without either a military footprint or capable local proxies, the United States will not be able to “mow the grass” of mid and low-level terrorists in Afghanistan with anywhere near the efficacy with which it could do so even a year ago. What regular counterterrorism does take place in Afghanistan will be in the nature of a gangland war, with the Taliban summarily executing any ISIS-K fighters it can get its hands on. But the killing of Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri on July 31 suggests that claims of the unseriousness of American over-the-horizon counterterrorism were overwrought.

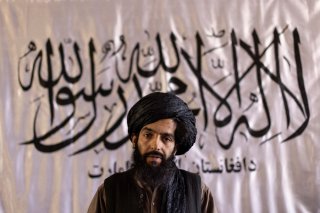

Zawahiri, emir of Al Qaeda since 2011 and the subject of a worldwide manhunt for an entire decade before that, was killed on the balcony of a house in Kabul by a pinpoint drone strike, his body likely shredded by bladed R9X Hellfire missiles, with no civilian casualties. The precision of the attack speaks to a patient and penetrating intelligence collection effort. A pattern of life was established and Zawahiri’s death was confirmed by a CIA ground team. The Taliban, of course, immediately disclaimed any knowledge of Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul. Their spokesman reiterated that they would not allow a threat to any other country to emanate from Afghanistan.

That this strike could be pulled off successfully in a denied environment like Afghanistan—and at a home owned by a top aide to Taliban deputy leader Sirajuddin Haqqani, no less—proves that over-the-horizon counterterrorism is far from “fictitious.” It is not a panacea, as many experts rushed to insist, but targeted drone strikes in Afghanistan remain a viable and useful U.S. capability.

Even in Washington, though, Zawahiri’s death was a blip on the radar. By noon that day, it was off the top of the New York Times’ website. To both elites and the average American, transnational jihadist terrorism is far, far down the list of major worries. Fewer than one percent of Americans listed it as their top concern this summer.

In the wake of the September 11 attack, terrorism was, for a time, successfully portrayed as a near-existential threat. The foreign policy conventional wisdom in Washington immediately became interventionist. Extremism and ungoverned spaces around the world could not be ignored or contained; problems would not stay “over there.” The Middle East was the original swamp that needed draining.

The events of the succeeding two decades, however, have largely made the opposite case. The wars came home to America not through enemy attacks (with the exception of a handful of “lone wolves”), but by perverting and radicalizing American culture, society, and politics. The Covid-19 pandemic then exposed a superpower that lacked production capabilities, public health competence, and basic societal concurrence. The threat from a few foreign fanatics seems trivial by comparison.

Afghanistan’s problems are now her own. Absent a major, credible transnational terrorist threat, Afghanistan has returned to where it should have always been within a year of the Taliban’s overthrow in 2001: a peripheral concern of the United States and the West. Whether this relegation will ultimately help or hinder the 40 million Afghans now living under Taliban rule is another question altogether.

No comments:

Post a Comment