In the preface of ‘Mes Rêveries’, Marshal Maurice de Saxe states the following: [i]

“War is a science so obscure and imperfect that custom and prejudice confirmed by ignorance are its sole foundation and support; all other sciences are established upon fixed principles… while this alone remains destitute.”

However, this belief is a stand-alone in the Age of Enlightenment, a time in which it was commonly believed that war, just like any other domain, must surely obey some laws and scientific principles. Besides, this quest for the principles of war did not spare other eras. From Sun Tzu and Xenophon to Fuller and Foch, an abundant literature in strategic thought offers various perspectives on what these principles might be and how many can we account for.

One can wonder, however, what utility these principles have for the strategist when there are so many. Indeed, no two wars are alike, and in the absence of fixed principles of war, the precepts provided by some famous strategic thinkers in an older era within a completely different context would hardly seem to have any relevance in a present-day conflict.

Then why are we still producing principles of war and what are they for? How can they be of any use to the strategist?

I argue that while there are no fixed principles of war but rather an infinite multiplicity of principles, depending on the era, author, strategic culture and context; it is neither their number nor even their content that matters most.

The utility of the principles of war lies in their confrontation with one another, fostering innovation. Their strength, indeed, is conditional, and “they are only useful once we understand how relative they are”.[ii]

Consequently, they are mostly ways for the strategist to feed his intuition. They allow him to internalize features, deepen his expertise and improve his judgement. But the strategist needs to be aware of the relativity of those concepts and understand what their practical assumptions are. Thus, it is all about how these principles are delivered and how they are understood.

In this essay, I first look at the principles of war themselves, where they come from and how they are reflective of different understandings of war. Then, I argue that only their confrontation with one another can lead to a useful reflection for the strategist. Finally, I show that this phase of internalization of knowledge into the strategist’s own intuition is what is really at stake regarding the principles of war, since strategy is, first and foremost, an art of synthesis.

The Principles of War

The search for principles governing the phenomenon of war is a long historical journey. We can dissociate, however, different approaches depending on one’s understanding of the nature of war. One of these approaches is to consider war as a science, obeying a clear set of laws and fixed principles. Principles, in this case, are axioms that act as general laws and rules, applicable to any conflict. This approach was especially fashionable during the 18th and 19th centuries, starting with the works of French marshals such as the marquis of Puységur, Folard, Joly de Maizeroy and Guibert.[iii] War was then sometimes merely considered as a branch of applied physics and mathematics. This perspective on war reached its pinnacle with the works of the Welsh general Henry Lloyd and Prussian theorist von Bülow[iv], aiming to completely erase the role of chance and hazard in the conduct of warfare. Jomini, although moderating their excesses, would greatly inspire himself from these theories by presenting war through a geometrical lens and believing in fixed principles.[v]

The legacy of these authors goes a long way, and the quest for a scientific understanding of war remained an attractive idea. Indeed, in 1926, British officer J.F.C Fuller categorized nine principles of war that highly influenced the current military doctrine of the United States[vi] and the United Kingdom[vii] : objective, offensive, mass, economy of force, maneuver, unity of command, security, surprise, and simplicity.[viii] In France, Marshal Foch posited three principles that are still constitutive of the French military doctrine: concentration of force, economy of force and freedom of action.[ix]

But these principles are, in many aspects, arbitrary. Fuller’s own principles went from six, to eight, to nineteen, to nine over the years. Despite some consistency from one country to another, these disparate principles simply reflect a particular understanding of the world and most importantly in the case of doctrines, a specific strategic culture.

For instance, Chinese principles of war differ considerably from western ones. Relying on the works of two PLA colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui,[x] its doctrine puts considerable emphasis on alternative methods to conventional confrontation. It also relies on a Confucian strategic culture which puts typical emphasis on indirect approaches to a problem.

Consequently, principles of war are never fixed, and their refinement is continuous. They always depend on a certain understanding of war situated within a specific context. Principles of war devised by Brodie, Sokolovski or Morgenthau regarding nuclear warfare obviously differ from principles of war devised by Mao Tse Tsung for revolutionary warfare. The same goes for Liddell Hart’s principles for indirect warfare or Ludendorff’s principles for total warfare.

New phenomena such as conflicts in the cyber domain, outer space, the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and hybrid warfare potentially call for new principles which do not make previous principles of war irrelevant, but simply account for a change in context.[xi]

In that way, Robert Leonhard fails to understand, while making a very interesting suggestion of new principles for the information age[xii], that principles of war are nothing else than a demonstration that, as Clausewitz stated, ‘war is a chameleon’.[xiii] The introduction of new principles is useful not because they are better than older ones – after all, they are subject to the same biases and arbitrariness – but because the contrast they bring with the older ones is thought-provoking. Most importantly, it is not stubborn adherence to the principles that makes them useful and helpful. Adhering to fixed principles would likely reduce the engagement of the strategist with other principles and partially blind his understanding of war. I shall now argue why the utility of these principles lies in their confrontation.

Confronting principles and the essence of strategy

If strategy shall be considered as a science, then it can only be “a science of accident” according to the Aristotelian sense of the term.[xiv] It means strategy is entirely dependent on the context and the project it serves. As a theory of action, strategy combines every available idea to arrive at concrete conclusions. Consequently, it is the creative confrontation of ideas that allows the strategist to devise innovative ways to reach his goals. This is why French general V. Desportes calls strategy “the art of synthesis”.[xv]

Principles of war are useful ways to frame general concepts, ideas and features regarding the nature and conduct of war. But because strategy is all about contexts, it does not stand any universal truth. This is why the strategist cannot make use of a single set of principles of war, since they will never accurately account for the particular context of the war he will have to lead. He must confront various sets of principles; understand the tensions between them and what kind of conclusions they lead to. There is no systemic way to do it, and these confrontations will yield different conclusions for every individual. Indeed, “our knowledge and understanding of warfare is a science, but the conduct of war itself is largely an art.”[xvi] Confronting principles leads to innovative thought. Principles are thus mostly pretexts for discussion and creative thinking. Since strategy is an art where one must constantly come up with new ideas and solutions to new problems, principles of war constitute a very efficient intellectual tool in times of peace to think about these problems.

But the strategist does also make use of theoretical principles whilst conducting war. Chess, as a strategy game whose nature as a science or an art was long debated, is a perfect example of this. Our knowledge and understanding of the game of chess can be considered as a science but playing a good game of chess is definitely an art. Chess principles are numerous, and they evolve over time as we understand the game better, for instance thanks to AIs such as AlphaZero.[xvii] Throughout the course of a game, these theoretical principles come in and out of use. But it is not the player who has picked the best set of principles before entering the game who wins, but rather the one who is able to confront them through the course of the game and follow the ones most adapted to the situation on the board. Indeed, there are times when two good general principles, such as keeping a healthy pawn structure or developing pieces on active squares, come into conflict and the player must choose between them. By confronting them according to the unique necessities of the situation, he can make the right choice. In the conduct of war, the same thing happens. For instance, Fuller’s principles are interesting, but because resources are always limited it is never possible to maximize all of them: you have to make trade-offs. It is only by confronting the principles according to the situation on the ground that the strategist might be able to make the best decisions. All the value of the principles of war comes from this confrontation.

The form to leave the form: Internalization & Intuition

This essay so far has focused on the necessity of confronting principles in order to make use of them in actual action. But it must also take into account that in the conduct of a war, the time available to make a decision is extremely limited, and this process of confronting principles has to be quick. Principles, for this reason, were quickly ruled out as an efficient tactical device for US military personnel, and the top brass moved instead toward processes and systems of system analysis in order to teach decision-making to its military commanders.

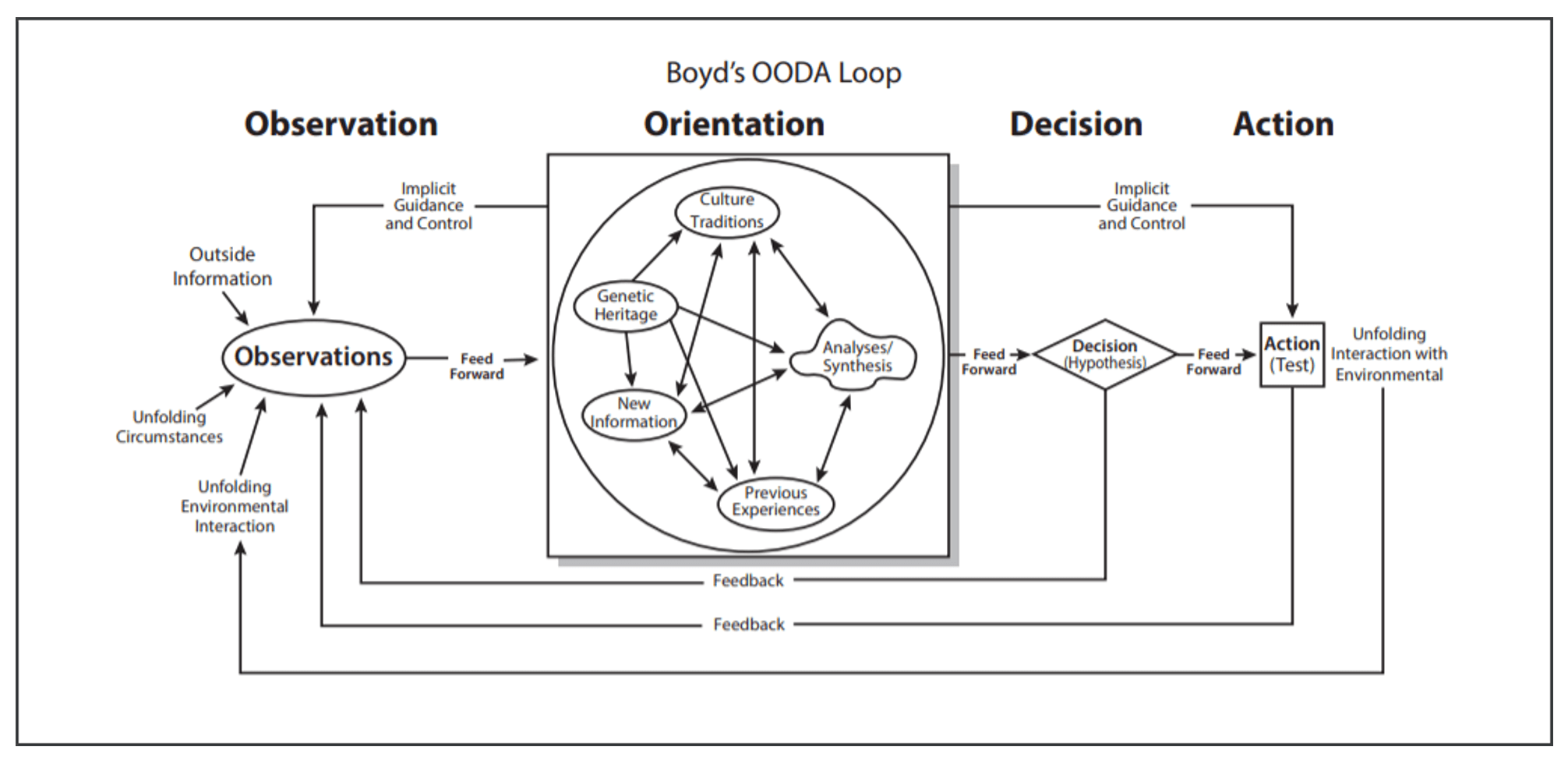

The example of the OODA loop, developed by US Air Force colonel John Boyd, is a good instance of these methods.[xviii] It aims to unify the contextual character of warfare and the need to act quickly with the theoretical tools the strategist is provided with and its own singularity. The OODA loop consists of a phase of observation (context), orientation (theory + singularity), decision and action.

In this loop, we can posit that principles of war are still part of the elements in the ‘orientation phase’ that will lead the strategist to a synthetic assessment of the situation so that he can make a decision. They are being internalized into a large number of components that together constitute the strategist’s intuition. It is this internalization process that ultimately matters in order to assess the utility of principles of war. Indeed, as long as those remain distant theoretical concepts, they will never be truly taken into account in the orientation process. In ‘The Art of Learning’, chess master and martial art champion Josh Waitzkin suggests that a central aspect of high-level performance success is to be able to internalize complex knowledge and principles deeply enough so that one can access it without thinking about it.[xix] It then becomes part of one’s intuition and can thus be used effectively and efficiently in any context. He calls this process of internalization into intuition ‘to learn the form to leave the form’.[xx] Principles of war are no different: we learn about them to leap away from them.

Principles of war can hardly be useful to the strategist if he cannot have a practical grasp of them first. The problem is that at times of peace, there is no way to really experience the true utility of these principles and get a natural understanding of them. This is why it matters all the more to actively place principles in confrontation with each other, instead of simply learning how they apply in theory one after the other. The fact of thinking about these principles, why one sounds more appealing than another, confronting them while analysing a historical or fictional situation, or even better, using them directly while playing wargames, allows for a more intimate understanding of them and of their potential uses. This is a very personal process, and it requires an active engagement before these principles can be internalized and be used in a practical situation. Thus, I assert that doctrines are not of any use if they remain abstract references and distant guides for action. They are only useful when put in comparison with each other, especially with a potential adversary. To quote German historian Hans Delbrück, “since everything is uncertain and relative in times of war, strategic actions cannot come from doctrines, they come from the depth of one’s character”.[xxi]

Ultimately, principles of war are what we make out of them. Some principles will have greater resonance in some minds than others. Blind adherence to any set of principles will lead to the worst results. What matters is not their content, but the thoughts and reactions these principles provoke. As such, they can be an excellent starting point for deeper intellectual investigation of some features of war, and eventually improve one’s natural understanding of the conduct of war. Once internalized, they can prove to provide a useful unconscious mental framework in order to find creative solutions to a specific problem. Their whole point, in the end, is to provide the strategist with a better-nuanced intuition when the time comes to make difficult decisions.

Conclusion

This essay started with a quote from Maurice de Saxe, implying that no principle of war can truly be defined. This is true from a logical point of view, since strategy, being always concerned with contexts, cannot stand any universal law. However, it does not mean principles of war are useless.

They are always shaped according to one’s perception of the nature of war, strategic culture and understanding of a certain context. When confronted with one another, these principles are great ways to generate critical and creative thinking about deep features of war, and allow strategists a better grasp of what strategy is all about: the combination of means and ideas to reach a certain goal.

Discussing, comparing, and contrasting these principles allows for their progressive internalization into intuition as a useful framework for actual decision-making. This process of internalization is essential in order to be able to readily draw inspiration from these principles, but also to leap away from them when they seem irrelevant to the current situation. In that sense, world chess champion Garry Kasparov was accurate in saying that ‘rules are not as important as their exceptions’ – but it takes a deep understanding and internalization of the rules in order to spot these exceptions.

This relative utility of principles of war, and the fact that conducting warfare is all about continuously breaking these rules when necessary, is perhaps the reason why Napoléon never made a formal list of the principles behind his understanding of the art of war. He encompassed, however, the importance of imagination. And it is also by imagining new principles for new contexts that, eventually, we develop a better awareness of the strategic issues of tomorrow and how we can work our way through them.

No comments:

Post a Comment