Adam Segal

In June, even as the war in Ukraine raged, the head of the UK's National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) warned in a speech that the "biggest global cyber threat we still face is ransomware." "That tells you something of the scale of the problem. Ransomware attacks strike hard and fast," said Lindy Cameron, CEO of the NCSC, the government's main cyber defense organization. "They are evolving rapidly, they are all-pervasive, they're increasingly offered by gangs as a service, lowering the bar for entry into cyber crime."

The war in Ukraine has sparked a debate among analysts about the uses and efficacy of cyber operations during the conflict. Some have argued that cyberattacks have under-delivered; others that attacks, especially the attack against ViaSat, a provider of broadband satellite internet services, have in fact been disruptive and effective. Microsoft has released two reports not only detailing Russian cyber espionage efforts, but also stating that cyberattacks are “strongly correlated and sometimes directly timed with its kinetic military operations." Still others have argued that the most effective cyberattacks have been those mobilized by Ukraine's IT Army, though the use of hacktivists and proxy actors raises serious questions about the development of norms of responsible state behavior in cyberspace.

CFR's new Task Force on U.S. cyber policy first convened before the war in Ukraine started and finished its report in May (you can read the final report here). One of the first findings Task Force members put to paper echoes Cameron's speech: Cybercrime is a national security risk, and ransomware attacks on hospitals, schools, businesses, and local governments should be seen as such. The members of the Task Force thought it too early to reach any final conclusions about the efficacy of Russian cyberattacks on the conduct of the war, but were clear that the conflict in Ukraine demonstrates how closely intertwined cyber and information operations are. This has long been central to Russian and Chinese cyber operations; the United States has traditionally separated the two, though this may be gradually changing. Remarking on the conflict, Lieutenant General Charles Moore, Cyber Command deputy commander, noted, “Without a doubt, what we have learned is that cyber-effects operations in conjunction—in more of a combined arms approach—with what we call information operations traditionally, is an extremely powerful tool.”

In addition, the Ukraine-Russia war has reinforced another of the task force's major findings: norms of state behavior in cyberspace are more useful in binding friends together than in constraining adversaries. The United States and its allies have had some success in defining norms of behavior through the United Nations and other multilateral forum. Yet major actors have flouted the norms that they signed off on. Russia’s tolerance of ransomware gangs, for example, violates the norm of state responsibility, and operations against the power grid in Kyiv in 2015 and 2016 contravene the norm of noninterference with critical infrastructure during peacetime.

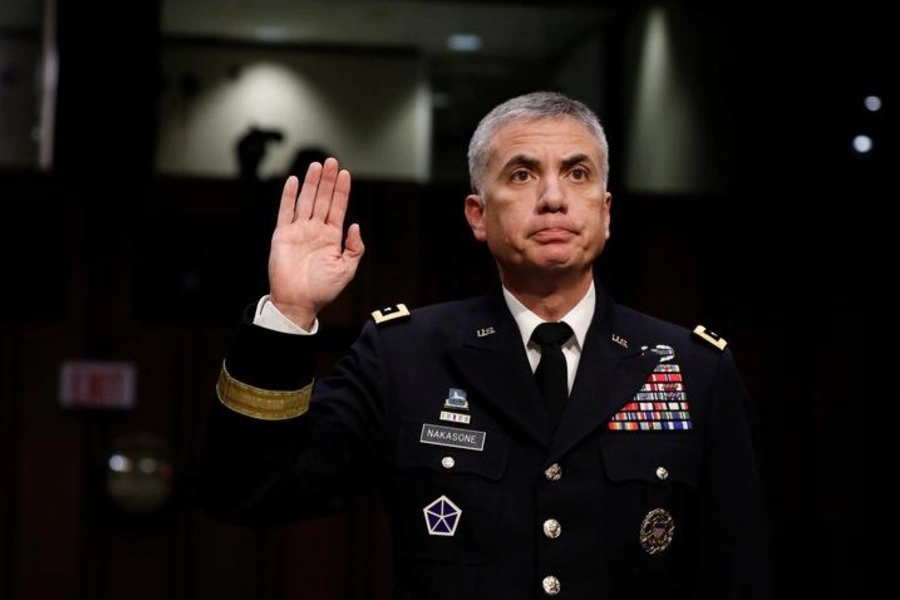

So how should U.S. policy evolve in the wake of the Ukraine-Russia war? The task force embraces the "defend forward" position developed by Cyber Command under the Trump administration along with targeted diplomatic pressure and self-imposed restraints on some U.S. offensive operations. In particular, the United States should develop a broad effort to erode adversarial capabilities, making them less effective by taking out infrastructure; exposing tools; and creating political, diplomatic, and economic pressure on finances, authorities, and leadership.

These efforts to disrupt adversary hacking operations would be paired with a clear statement that the United States will not conduct destructive attacks against electoral and financial systems. The United States and its partners should promote a norm regarding disruptive attacks against election infrastructure, banning efforts to disrupt voter registration, voting machines, vote counting, and election announcements. It should work with coalition partners to prevent, mitigate, and, when necessary, respond to destructive attacks on election infrastructure.

The global financial system is highly interconnected and depends on trust. Cyber operations directed at the integrity of any one part of the system could cascade into others, threatening the entire system and international stability. Washington should declare that it will not conduct operations against the integrity of the data of financial institutions and the availability of critical financial systems. Given that norms exert a weak limit on state actions in cyberspace, the United States and its partners should be prepared for their violation by increasing the resilience and redundancy of these critical systems. Financial institutions should regularly run exercises to restore the integrity of data after a cyberattack. The declaration of these norms, however, signals that these types of attacks will be considered off limits and would mobilize coalition partners quickly to respond if the norm is violated.

Moreover, to address the problem of states that actively harbor cybercriminals or ignore third parties using their digital infrastructure in offensive and criminal campaigns, the United States and its coalition partners could set a policy similar to the response to international terrorism that they will hold accountable any states that provide safe havens or do not cooperate in the takedown of criminal infrastructure or in law enforcement investigations, arrests, and extradition. Washington should exert diplomatic and economic pressure, but under certain circumstances could also reserve the right to take action against infrastructure used by these groups if the countries hosting it will not do so.

These policy recommendations are evolutionary, not a radical break from what the United States has been doing. Although a modified strategy assumes that the United States will more proactively use cyber and non-cyber tools to disrupt cyberattacks and that norms are more useful in binding friends and allies together than in constraining adversaries, the strategy also takes into account that the major cyber powers share some interests in preventing certain types of destructive and disruptive attacks. As with the Task Force's recommendations around digital policy (you can read about here), this strategy is more limited, more realistic, and more likely to succeed in achieving critical but finite goals.

No comments:

Post a Comment