Antonia Colibasanu

The G-7

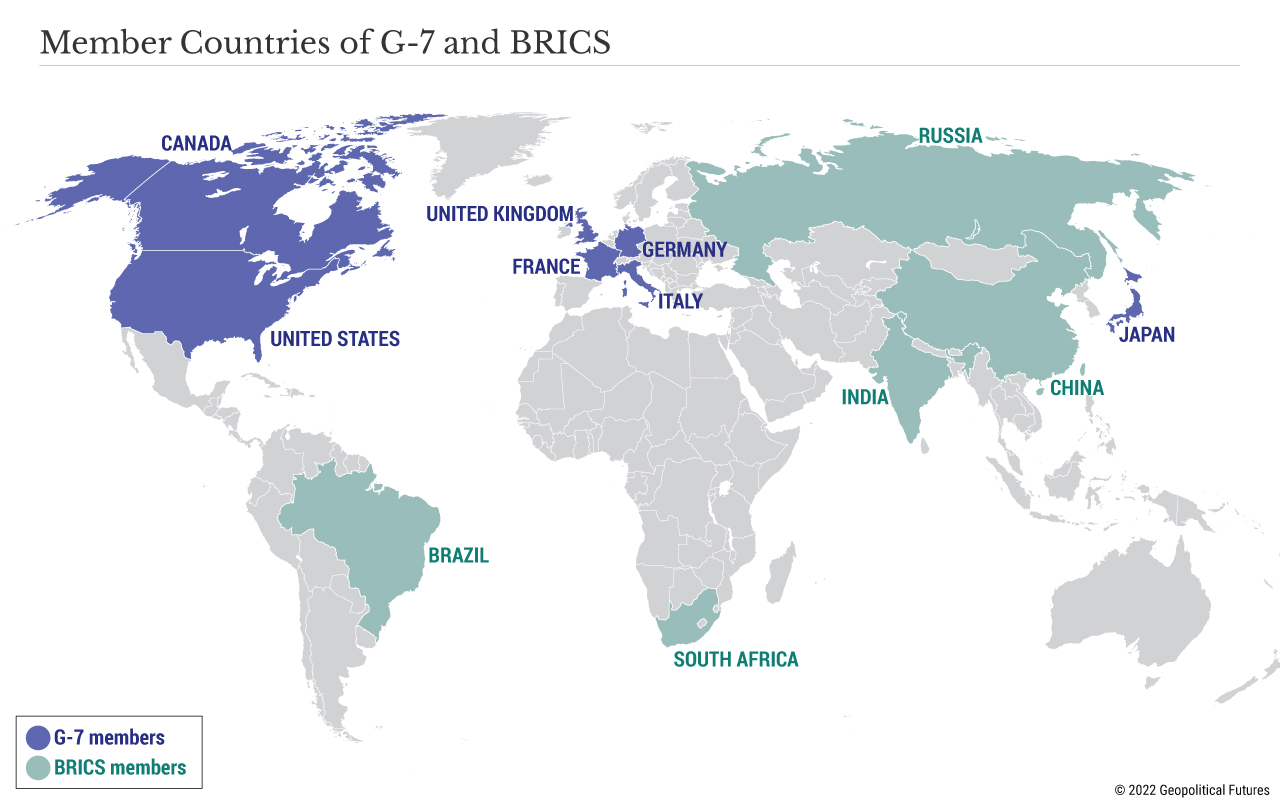

The Group of Seven consists of the world’s wealthiest democracies – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States – plus the European Union. Since Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, these countries have coordinated to support Kyiv in various ways while launching an economic war against the Kremlin. However, sanctions and Russian countermeasures have helped to drive up energy prices, exacerbating already high inflation and creating serious social and economic risks in much of Europe, which depends heavily on Russian energy. The war has also severely hampered Ukrainian grain production and exports, while high energy and fertilizer prices affect production elsewhere. The scale of these crises calls for high-level, coordinated solutions. The G-7 hopes to mitigate the economic pain on everyone except Russia while turning up the pressure on Moscow to end the war.

One element of that pressure campaign is a gold embargo, which was agreed to on Tuesday. Russia has used its enormous stockpile of gold to blunt the effect of sanctions and support its currency. With the West searching for new ways to pressure the ruble and the Russian economy without European energy sanctions, banning Russian gold imports is a logical step. The U.S. has prohibited gold-related transactions involving Russia since March.

Another measure, far from finalized, concerns a cap on the price of Russian oil. Revenues from energy exports have helped fund the war, and sanctions to date have only forced the price higher. The U.S. and others have already banned imports of Russian oil, but much of Europe is too reliant on Russian supplies and thus resistant to adopting similar bans. A price cap would in theory ensure that flows continue – Russia willing – while eating into Russia’s revenues. However, many questions remain about implementation, and Moscow has meaningful leverage. For instance, it could refuse to sell its oil at the mandated price, or it could shut more natural gas pipelines to Europe under dubious pretenses, as it is threatening to do with Nord Stream 1 to Germany. These countermeasures would come with their own costs for Russia, and it’s simply impossible to know which side could tolerate the pain for longer. What is clear is that the West has struggled to secure alternative energy supplies and is thus in a tough spot.

Zooming out, something more important is happening. The G-7, and the so-called West more generally, needs allies to help it defend existing international rules and norms and to help it reduce its reliance on Russian energy. It also needs allies against the potential food crisis, which is orchestrated by Russia – itself a massive food producer – via its destruction of Ukrainian grain storage facilities and a Black Sea blockade. To that end, the German hosts of the G-7 summit invited Argentina, India, Indonesia, Senegal and South Africa to join. In a statement, the G-7 countries announced their intention to pursue so-called Just Energy Transition Partnerships with the guest countries, indicating that all or some of them may help the West decouple from Russian energy. In the meantime, Germany and Senegal are discussing ways to jointly explore and develop Senegalese natural gas reserves. Argentina formally offered to become “a stable and reliable substitute supplier of Russian gas to Europe and of food to the world.” And India announced the relaunching of free trade talks with the European Union after a nearly decadelong freeze.

At the same time, there’s plenty of reason for caution. For example, most of Argentina’s gas reserves are undeveloped, and it needs significant investment to live up to its promises. For its part, India has yet to condemn Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. Tough discussions lie ahead. Not all players have chosen a side, and convincing the convincible will require compensation.

Russia’s Summits

While the West is recruiting allies, Russia seems to be having problems keeping its partners together. Earlier this month, Russia held its St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, gathering government and business leaders interested in working with Russia. The number of participants has declined significantly since Russian operations first began in Ukraine in 2014, but the forum still included leading figures from the Eurasian Economic Union as well as China, India, Venezuela, Cuba and Serbia.

During the event, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev made headlines when he said Kazakhstan would not recognize the breakaway Ukrainian Donetsk and Luhansk republics. He also said most non-G-7 countries preferred not to choose a side, while arguing that Russia has much to offer “friendly” countries. Over the weekend, apparently trying to limit the damage from deviating from the Kremlin’s script, Tokayev called Russia an important ally and said he had had a “nice meeting” with President Vladimir Putin. Russian repairs on a Kazakh oil pipeline will probably be completed this week, he added. (Western officials doubt that the pipeline is undergoing needed maintenance.)

The St. Petersburg forum followed the 14th annual summit of leaders from the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), a “southern” rival to the G-7 and U.S.-led blocs generally. At the summit on June 23, Putin asked his counterparts for support and closer economic ties to counteract Western sanctions.

So far, his calls have fallen on muffled ears. Though only Brazil voted to condemn Russia’s attack on Ukraine at a U.N. vote in March, the other BRICS members have stalled for time and avoided clearly choosing sides. They have taken advantage of Russia’s willingness to do business, while staying open to Western trade and investment. India has significantly increased purchases of Russian energy since the war started, but it also attended the G-7 and restarted trade talks with the EU. South Africa typically aligns with Russia, but it too attended the G-7, where it discussed energy projects with Germany. And Argentina, as mentioned, sought energy and agricultural investment from the G-7.

Putin also promoted the idea of a BRICS basket-based currency and alternative to the SWIFT interbank messaging system, noting that Russian trade with the BRICS group had increased by 38 percent in the first quarter of 2022. The effort is intended to help Russian trade partners avoid becoming subject to Western sanctions, which remains a significant concern for them. For example, cargo dispatchers in China that want to send goods to Europe need to choose whether to do so via Russian or Kazakh territory.

Based on available data, more and more are choosing the latter. The Kazakh national railway company reports that the Aktau Sea commercial port, the Kuryk port and the Aktau Marine North Terminal have doubled their shipping volume since the beginning of the year. China’s Belt and Road Initiative already envisaged Kazakhstan as a transit zone for trade to and from Europe. The war in Ukraine is only accelerating the process and augmenting Kazakhstan’s regional importance. The strategic partnership between Kazakhstan and Turkey also supports this new transport map. On May 10, Tokayev and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met to discuss diversifying oil export routes to China and Europe, “including the use of Turkish transport corridors.”

This is important context for Tokayev’s remarks in St. Petersburg. More than ever, the Kazakh president has important leverage in his relationship with Putin. This also helps to explain why Putin is attending the Caspian Summit in Ashgabat on Wednesday, where investment projects will be further discussed. The Kremlin doesn’t think proposed new corridors will be effective – the Caucasus is too unstable – but worries about the development of regional initiatives without its participation.

The concluding BRICS statement referred to members’ positions expressed at the U.N. Security Council and U.N. General Assembly, and reiterated their support for U.N. humanitarian assistance to the region. Such nebulous statements only reaffirm the hesitation countries have in siding outright with Russia. However, neither are they eager to side with the West. In an economic environment ruled by uncertainty, flexibility is priceless.

No comments:

Post a Comment