Steven Pifer

Twenty-six years later, Russia is more than three months into a massive invasion of Ukraine. This has understandably led Ukrainians to question the wisdom of giving up those nuclear arms, and Vladimir Putin’s war has dealt a blow to future efforts to arrest nuclear proliferation.

Ukraine’s path to denuclearization. When the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991, Ukraine found itself with about 4,400 nuclear warheads on its territory—1,900 strategic and 2,500 non-strategic or tactical warheads—as well as the SS-19 and SS-24 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and Blackjack and Bear bombers to deliver the strategic warheads. Russia quickly arranged the transfer to its territory of Ukraine’s non-strategic weapons, which was completed in May 1992. But the strategic weapons remained.

The government of then-newly-independent Ukraine was inclined to become a non-nuclear weapons state. Ukraine’s July 1990 declaration of state sovereignty said that the country would not accept, produce, or purchase nuclear arms. But, before giving final assent to their removal, Ukrainian officials set out a number of questions to be addressed. First, nuclear weapons were viewed as conferring security benefits, and Kyiv sought guarantees or assurances for its security after they were gone. Second, Ukrainian officials wanted compensation for the value of the highly-enriched uranium contained in the warheads. Third, as a successor to the Soviet Union for purposes of the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), Ukraine would have to eliminate the ICBMs, ICBM silos, bombers, and other nuclear infrastructure on its territory—but Kyiv was unsure how to cover the costs of doing so given its uncertain economic prospects.

Ukrainian and Russian officials negotiated in bilateral channels on these questions in 1992-1993. They kept US officials apprised, in part because Kyiv hoped the United States would join in providing security guarantees or assurances. Washington agreed to do so, but insisted on the term “assurances” instead of “guarantees,” as the latter implied a commitment of military force that US officials were not willing to provide to Ukraine in the event of a violation of its sovereignty or territorial integrity.

In September 1993, following a meeting between Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and Russian President Boris Yeltsin, the two sides reported that the issues over the transfer of the strategic nuclear warheads to Russia for their elimination had been resolved. However, this agreement collapsed within days.

Fearing Kyiv and Moscow alone might prove incapable of reaching agreement, US officials subsequently decided to engage more directly. The United States was also concerned about the entry into force of START after the Russian government had conditioned it on Ukraine acceding to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapons state. Russian officials welcomed US participation, because they understood that Washington shared their goal of getting the nuclear weapons out of Ukraine. Ukrainian officials also welcomed US participation, believing they would have support from the United States on certain issues.

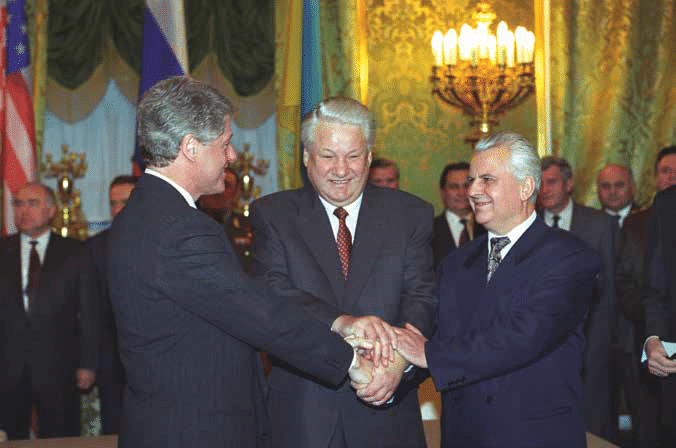

Following trilateral discussions in Kyiv in mid-December 1993, US officials saw the possibility of coming to closure and invited Ukrainian and Russian officials to Washington in early January 1994. Negotiations there produced the Trilateral Statement, signed by Kravchuk, Yeltsin, and US President Bill Clinton on January 14, 1994, in Moscow.

Terms of the deal. The Trilateral Statement reflected a number of points, including Ukraine’s commitment to accede to the NPT as a non-nuclear weapons state “in the shortest possible time,” agreement on the simultaneous “transfer of nuclear warheads from Ukraine [to Russia] and delivery of compensation [for the value of the highly-enriched uranium in the strategic nuclear warheads] to Ukraine in the form of fuel assemblies for nuclear power stations,” as well as the US commitment to provide assistance to help Ukraine eliminate the strategic delivery systems on its territory as required by START.

The Trilateral Statement also contained the specific security assurances that the United States, Russia, and the United Kingdom would provide to Ukraine once it acceded to the NPT. Security assurances included commitments “to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders” of Ukraine and “to refrain from the threat or use of force” against Ukraine. These commitments were later reflected in the Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances signed in December 1994.

In addition to signing the Trilateral Statement, the three leaders exchanged confidential letters. These reflected Kyiv’s agreement that all remaining nuclear warheads would be transferred to Russia for elimination by June 1, 1996, and Moscow’s agreement to provide compensation to Ukraine for the non-strategic nuclear warheads that had already been removed.

In February 1994, Russian and Ukrainian officials met bilaterally and agreed on schedules for the transfer of the strategic nuclear warheads to Russia and the transfer of fuel assemblies to Ukraine. They also agreed on the compensation that Ukraine would receive—a debt write-off—for the value of the highly-enriched uranium in the non-strategic nuclear warheads. The first transfers began shortly thereafter.

In November 1994, Ukraine’s parliament—Rada—approved its instrument of accession to the NPT. That set the stage for Clinton, Yeltsin, newly-elected Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, and British Prime Minister John Major to receive Ukraine’s instrument of accession to the NPT and sign the Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances on December 5, 1994. Ukraine and Russia completed the respective transfers of nuclear warheads and fuel assemblies a year-and-a-half later.

Russia’s betrayal and its consequences. In February 2014, however, Putin’s Russia—in a gross violation of its own commitments laid out in the Budapest Memorandum—used military force to seize Crimea from Ukraine and subsequently annexed it. Shortly thereafter, in March 2014, Russian security and military forces became involved in the conflict in Donbas in eastern Ukraine—a conflict that claimed approximately 14,000 lives prior to February 2022, when Russia launched a full-scale invasion of its western neighbor.

Had Ukraine kept nuclear weapons, its relations with the United States, Europe, and organizations such as the European Union and NATO would most likely not have developed as they have over the past 25 years, and Kyiv would have had a huge problem with Moscow—but the underlying facts of the case would have looked different. Consequently, Ukrainians understandably now look back and question the wisdom of giving up nuclear arms. Would Russia have acted as it did in 2014 and 2022 had Ukraine kept some of its nuclear warheads? Russia’s betrayal of its security commitments to Ukraine—not to mention the brutality of the war that the Russian military has waged—will almost certainly make Kyiv leery of any future agreement with Moscow.

Meanwhile, consistent with what US officials had told their Ukrainian counterparts at the time of negotiating the security assurances, Washington has provided significant military assistance to Ukraine, including anti-armor missiles, armored vehicles, heavy artillery, and large amounts of ammunition—an assistance package worth more than $4.5 billion since January 2021 alone. In addition, in May 2022, the US Congress passed another multi-billion-dollar package of military aid and economic support for Kyiv. The United States has also worked with the European Union and other states to impose major economic sanctions on Russia.

The war is a tragedy for Ukraine, which has suffered the deaths of thousands of soldiers and civilians and immense physical damage. But it is arguably also a disaster for Russia, which has lost many more thousands of soldiers, will suffer great economic pain as a result of Western sanctions, and faces a rejuvenated—and very likely soon to enlarge—NATO.

Non-proliferation efforts may turn out to be another important casualty of the war. Russia’s blatant disregard for its 1994 commitments to Ukraine has discredited security assurances in the toolkit of non-proliferation efforts. What Russia (which has the world’s largest nuclear arsenal) has done to Ukraine (a country that gave up its arsenal) likely will rank high in the mind of those in future countries who consider whether to acquire, or to give up, nuclear weapons.

No comments:

Post a Comment