John Pollock

After a brief interval, the roof of the world is once again the venue for tensions between Asia’s continental rivals. Eighteen months on from the withdrawal of forces from Pangong Tso, China has returned to the area and done so with its telltale signature seen across the Himalayas: infrastructure. Where in January 2021 the light infantry and main battle tanks of the Peoples Liberation Army were deployed to foxholes and temporary encampments, today observers are seeing the signs of a more permanent Chinese presence. Bridges, roads, and upgraded military cantonments are appearing in proximity to the disputed lakes of Pangong and Spanggur, replicating a pattern seen across Ladakh and Aksai Chin.

Ladakh, which in August 2020 seemed on the cusp of a high-altitude conflict not seen since Kargil in 1999, has witnessed a sustained increase in ‘dual-use’ infrastructure by China upon the ground occupied by its egress across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) two years ago. On the Depsang Plains, near India’s strategic Daulat Beg Oldi airbase, all-weather encampments are being constructed by the PLA alongside new defensive revetments and roads. At Hot Springs and Gogra, similar cantonments are appearing equipped with solar panels. Across the Tibetan plateau, but tellingly near both Doklam and Ladakh, new helipads are being constructed which can facilitate the rapid deployment of the PLA to contested areas. The pattern emerging should come as no surprise. The proliferation of such infrastructure mirrors those at Doklam and along the Sino-Bhutanese border where a PLA presence remains active to this day despite claims of drawback in 2017. Indeed, the developments on the Doklam plateau feel increasingly like a precursor to China’s renewed buildup along the LAC.

Pangong Tso: A Reinforced Presence

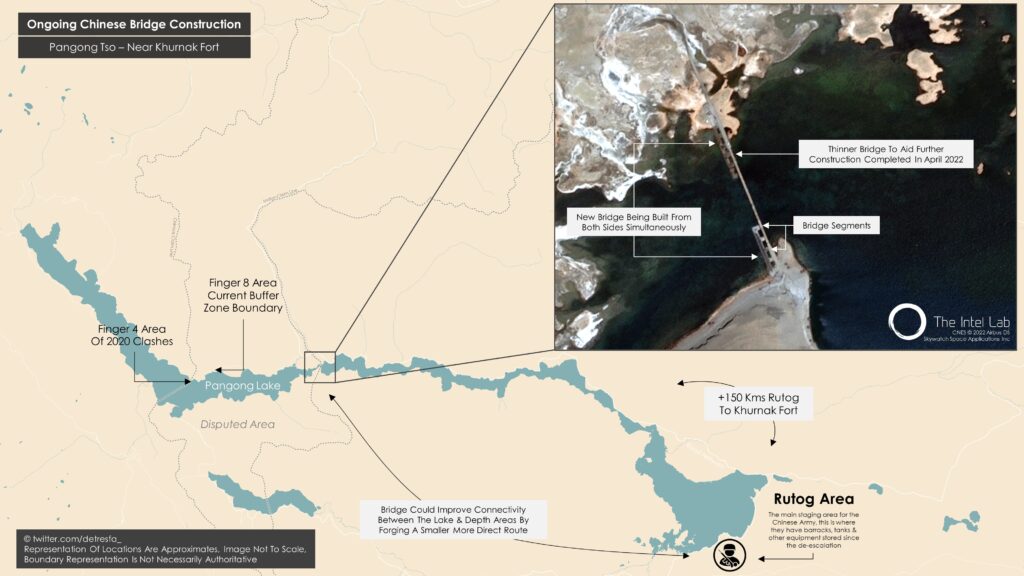

Since the first satellite images became publicly available in January 2022, two bridges are now visible at Pangong Tso. Both sit 20 kilometers east of Finger 8 on the Chinese side of the LAC. The first, the smaller of the two, was completed in April and seems designed to facilitate the movement of foot traffic between the north and south banks. While initially thought to be part of an effort to move infantry more quickly towards Fingers 4 through 8, open-source intelligence analyst Damien Symon has noted that the bridge appears to be in support of a far-larger second overpass. When completed, the second bridge will enable the lake to be crossed by heavier traffic, likely PLA vehicles.

With the Indian army able to deploy from their encampment at Dhan Singh Thapa, between Finger 2 and Finger 3, the choice of location is no accident. Both bridges are in proximity to the contested Khurnak Fort, an area captured by China in 1959 ahead of the Sino-Indian border war. In the last few months, Khurnak has seen an expansion in PLA activity, including expanded living quarters and a new vehicle park. More importantly, the bridges at Pangong Tso are located near a section where the 134 km lake narrows to just 350 meters. The new bridges thus look set to provide the Chinese military ease of access to both Khurnak and the Sirijap complex, a flat plain that serves as a staging ground for the PLA to deploy to the ridges overlooking Pangong Tso. Given the proximity of the PLA’s Rutog military garrison to these two overpasses, it appears local Chinese commanders have recognized the need to reduce the distance it takes to deploy from Rutog to Khurnak and Sirijap which the bridges will accomplish by cutting the journey by 150 km. At the present rate of work, PLA engineers seem intent on delivering this shortened route to Pangong Tso by the end of the summer.

Image courtesy of Damien Symon (Twitter @detresfa_)

Image courtesy of Damien Symon (Twitter @detresfa_)Near Rutog, more expansion is visible with a large helipad under construction, with shelters for up to a dozen helicopters and new command and control facilities. At the Rutog garrison itself, photographs published by Chinese state media, as well as satellite images, show the base is being reinforced. New accommodation units are being constructed alongside munitions depots, and surface-to-air missile batteries, with the facilities expected to increase the capacity of the garrison from a reported strength of 5,000 in 2019 to potentially as high as 18,000. In the event of a “surge” by the PLA, Rutog would thus be able to host two to three brigades in a location just 100 kms from Pangong Tso. Such a force, which would also be reinforced by new support facilities at the sister lake of Spanggur Tso, would increase the size and scope of the PLA’s capacity to deploy to Pangong Tso and give China further leverage at Moldo, where direct face-to-face negotiations concerning conduct on the LAC are held by Indian and Chinese flag officers.

Doklam: A Template Being Repeated?

The latest moves by China at Pangong Tso are consistent with a now recognized pattern of recent behavior in the Himalayas. Once the PLA are established in an area, they rarely leave without lengthy negotiations and when they do a residual presence invariably remains, sometimes directly in the contested area and other times adopting an “over the horizon” approach. Tellingly in both scenarios, once tensions have reduced and the troops have withdrawn, engineering equipment, roads and accommodation blocks soon take their place. This has been the modus-operandi for the PLA near the Doklam tri-juncture with Bhutan for the last five years, which despite its distance from Pangong Tso, follows the same pattern and may yet indicate what lies ahead.

First the context. Following the 72-day standoff at Doklam in 2017, the Modi administration has made clear since that it achieved a return to the status quo ante, with Indian forces withdrawing to Sikkim and the PLA returning to Tibet. This was presented in the immediate days and weeks after the withdrawal by the BJP and sympathetic voices as a nationalist victory for Indian military prowess and diplomacy. It wasn’t for the first time however that a declaration of victory was premature. Almost immediately after the drawdown in the summer, China poured reinforcements into the Chumbi Valley adjacent to Doklam. PLA patrols resumed and continued to test the response times of the Royal Bhutanese Army, as well as the Indian mountain brigades deployed near Nathu-la in Sikkim.

The result of a more active PLA shifted the domestic strategic discourse within Bhutan. The Bhutanese government, mindful of anti-Indian sentiment among younger Bhutanese, returned to a policy of overt silence on all border incursions.

Despite the Bhutanese governing elite being sympathetic towards India, popular opinion within Bhutan remains anxious of the country being caught between two regional superpowers, with a limited agency to influence events occurring within its territory. These anxieties have fertile ground given the long-standing concerns by Bhutanese over India’s leverage over the country’s leaders and its role in New Delhi’s defense plans that see the kingdom as a buffer with China. The result is that incursions by PLA patrols in the contested northern areas of Jakarlung and Pasamlung have since gone unacknowledged by Thimphu and have only been made public by the work of researchers. Work by Robert Barnett and his team at University London SOAS revealed last year that the PLA has been preventing access to Dermalung, a key artery into Tibet for Bhutanese pilgrims for example. Unconfirmed reports were also circulated of more aggressive patrolling by the PLA at Sinchulung, Dramana, and Shakhatoe. All of which are claimed by China and are just north of Doklam. Tellingly Bhutan has not invoked the mutual defense clause of the 2007 treaty in response to these incursions, despite the presence of the Indian Military Training Team in the country, and the support it might offer the Royal Bhutanese Army. The result is a more wary Bhutan and an uncertain level of Chinese activity within the kingdom. A return to the status quo, this was not.

Rather than deescalate after Doklam, the PLA’s Tibetan Military District has seemingly upped the pressure on Bhutan. In the years after the Doklam standoff, Chinese villages, such as Gylaphug and Pangda, and other settlements, including roads leading to and from China, have been identified within Bhutan by open-source intelligence analysts. In the west of Bhutan, within the Chumbi valley, as well as on the Doklam plateau and in contested border areas, the comparisons with Pangong Tso bode ill for any hope of a PLA de-escalation. Satellite images from Maxar/Google Earth reveal that China has built a series of projects, with a clear reorientation of military forces towards Doklam, increasing connectivity with Tibet and allowing PLA and civilian contractors to rotate in a permanent presence that can exploit gaps along the Bhutanese border and deploy with enough strength and speed to prevent any reversal of China’s gains.

Work undertaken by CSIS in 2019 highlights the construction of fighting positions, communications towers, ammunition bunkers, helipads, roads and powerplants in proximity to the Doklam plateau and likely even on it, and all in place well before the PLA’s foray into Ladakh. The presence of large amounts of Chinese vehicles and the deliberate attempts to camouflage the buildings denote a clear military intent despite its ‘dual-use’ nature. Alongside the revelations relating to Chinese villages within internationally recognized Bhutanese territory, there is also evidence of surface-to-air missile batteries being established at the Naku La and Doka La passes. Weapons intended not only to give the PLA further reach within the kingdom but to deter Indian Air Force P-8 Poseidon surveillance flights, as Bhutan has no air force to deter.

A Changed Status Quo

The lessons for Pangong Tso from Doklam are stark. Once China secures the territorial gains it has acquired, it will then move towards an increased presence with growing capabilities. PLA patrols will soon have the infrastructure in place to be more frequent, better equipped, and deploy with faster response times. The status quo that existed at Pangong and Spanggur Tso prior to April 2020 is thus gone and unlikely to return. Comparable to what we are seeing along the Bhutanese frontier, at Pangong Tso the bridges, roads, and all-weather accommodation are key signals that the PLA will be present along the contested lake for the medium- to long-term. The inevitable implication is that in the near future, China will, once again, conduct sorties that will bring it into contact with India’s XIV Corps, headquartered at Leh. Having been outmaneuvered when India’s Special Frontier Force scaled the heights of the Kailash mountain range, overlooking Chinese camps at Spanggur Tso, and with its deployed troops suffering from frostbite and altitude sickness, it now seems as if the PLA has learnt the value both of maneuverability in mountain warfare and the logistical means to support such operations. The result is that the PLA is working to secure the avenues for delivering their own fait accompli, should tensions with India’s Northern Command reignite.

In many ways this signals the recognition that the Central Military Commission is finally taking India seriously as a military actor. At Pangong Tso, but also on the Depsang Plains, Hot Springs, and Gogra, the PLA is looking to retain the option to escalate should another clash occur along the lines seen at Galwan. The developments on the LAC however are also a recognition that China sees at Pangong Tso and Doklam vulnerabilities that it can exploit to India’s strategic detriment. A pressure point, that if enacted, would inevitably draw New Delhi’s attention further north. In doing so any strategically minded foreign policy would instead be replaced by nationalistic impulses and ensure that India’s bloated defense budget continues to favor the Indian Army’s two-front land doctrine towards China and Pakistan. To undertake this path would ignore the very means with which India can actively challenge Beijing in the Indo-Pacific and perhaps even give the leadership in Zhongnanhai pause, namely, an expanded and modernized Indian Navy equipped with three aircraft carriers, nuclear attack submarines capable of operating beyond the Indian Ocean, and an operational alignment with Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force and the United States 7th Fleet.

No comments:

Post a Comment