Tim Brinkhof

“What can be expected of man since he is a being endowed with strange qualities?” Fyodor Dostoevsky asks in his 1864 novella Notes from Underground. “Shower upon him every earthly blessing, drown him in a sea of happiness, so that nothing but bubbles of bliss can be seen on the surface; give him economic prosperity, such that he should have nothing else to do but sleep, eat cakes and busy himself with the continuation of his species.”

“Even then,” Dostoevsky continues, “out of sheer ingratitude, sheer spite, man would play you some nasty trick. He would even risk his cakes and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive good sense his fatal fantastic element. It is just his fantastic dreams, his vulgar folly that he will desire to retain, simply in order to prove to himself—as though that were so necessary—that men still are men and not the keys of a piano.”

When Dostoevsky wrote these lines, Russian writers were obsessed with the idea of utopias. They wrote stories and treatises in which they envisioned how the increasingly dysfunctional czarist empire could be replaced by a society devoid of suffering or conflict. Their vision for the future sparked the imaginations of numerous individuals, from armchair philosophers to armed socialist revolutionaries eager to turn such speculative fiction into a political reality.

Dostoevsky, however, was not impressed. As explained by the quote above, the author of Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov believed that utopias were, by definition, incompatible with human nature, which gravitates toward freedom. People, he argued, would rather be free in an imperfect world than unfree in a perfect one. Since the line between utopias and dictatorships is unclear, the writer also believed that the planning one would inevitably result in the creation of the other.

Notes from Underground was not the first text to address this dilemma. The relationship between utopias and human nature has puzzled thinkers for centuries, with different time periods producing conflicting responses. Plato saw no contradiction between the two. Nowadays, thanks in part to the bloody legacy of the Soviet Union and other communist countries, most readers living in the Western world tend to side with Dostoevsky. But is the author’s conclusion really that convincing?

Life under Plato’s philosopher-kings

While Plato’s dialogues shaped the development of democracy in Europe and beyond, his ideal society as described in the Republic is hardly democratic. This society is ruled not through popular vote, but by philosopher-kings: rulers who govern through philosophy. Not every member of society is eligible to become a philosopher-king; rather, they are selected from a ruling elite. Eligibility is based not on strength, wealth or lineage, but on love for the truth and ability to reason.

“Until philosophers are kings,” the character of Socrates tells his interlocutors, “or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy…cities will never have rest from their evils,—no, nor the human race, as I believe,—and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day.” To modern readers, Plato’s trust in philosophers may sound short-sighted and supercilious. However, the Greek thinker had his reasons.

Plato divided the soul into mind, body and spirit. Founding a tradition that stretches from St. Augustine to the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, he saw bodily and spiritual urges like jealousy or lust as the roots of all evil; these urges – not to mention the pains they lead to – could be remedied by the faculty of the mind: reason. Just as Socrates used philosophy to reveal the benefits of self-control, so too would the philosopher-king have used philosophy to keep society in perfect balance.

The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius is often cited as an example of a philosopher-king. (Credit: Nicholas Hartmann / Wikipedia)

“In in Plato’s nondemocratic [Republic],” reads one article, “ensuring justice means that certain elements of the state (as in the soul) obey others. The spirited element in both the soul and the state (in the soul, anger and pride; in the state, the guardian class of warriors) together with the appetitive element (in the soul, the desires; in the state, the merchants and craftsmen) must be subjugated to the wisdom of the “best” class of people, the philosopher-kings, in whose souls rationality is triumphant.”

Reason governs all aspects of life in Plato’s Republic, even the production of art. When the Republic goes to war, says Socrates, its poets would not be permitted to write about cowardice as doing so might soften the resolve of the soldiers. Plato’s distrust of civil liberties may be linked to his experiences with Athenian democracy, a system in which voters were easily convinced by demagogues who coaxed them into entering the Peloponnesian War and authorizing the death of Socrates.

The Republic had a lasting influence on utopian writing in the West. St. Augustine, author of the 426 book City of God, also envisioned a universe in which existence unfolded according to the direction of a higher (this time religious) power. Thomas More, who penned the 1516 text Utopia, inherited Plato’s anti-democratic sentiment; his perfect world abolishes private property, a right which America’s Founding Fathers would etch into their country’s constitution centuries later.

Russian utopia before the Soviet Union

More and (to some extent) Plato never meant for their utopias to be realized; they were thought-experiments, not workable blueprints for actual regimes. This stood in stark contrast to 19th-century Russia, a country where books were generally written with real-world aspirations in mind. For this reason, utopian thought often stood at the forefront of political movements. One of the earliest examples of this were the Decembrists, who emerged after the sudden death of Czar Alexander I.

Like the socialist parties that followed in their footsteps, the Decembrists split into several branches. The more moderate of these branches drafted a constitution which would have turned Imperial Russia into a federal republic not unlike the United States. The underlying thought of this document, according to the historians Alexander Riasanovsky and Alvin Rubinstein, was that self-determination — not dictatorship — would lead to peace and prosperity.

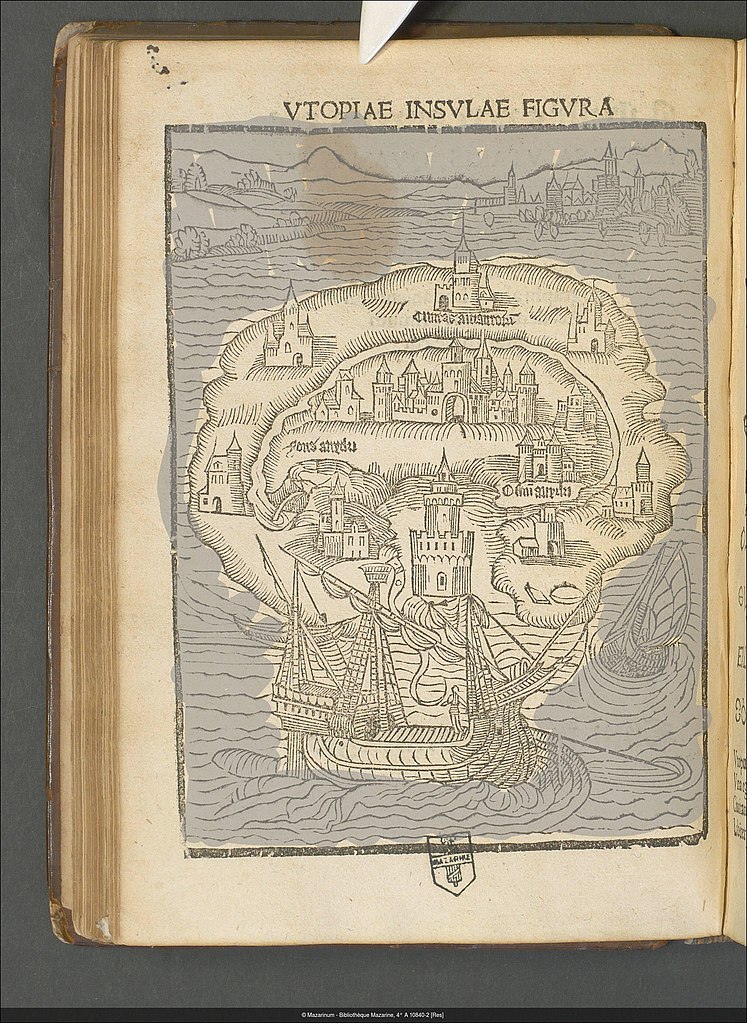

An illustration of Thomas More’s utopia. (Credit: Bibliotheque Mazarine / Wikipedia)

Another, more radical, branch of the Decembrists formed around the revolutionary figure of Pavel Pestel. In a treatise titled Russkaya Pravda, Pestel stated his belief that federalism was “alien to Russia’s historical experience” and would lead to “political disintegration.” His vision for the country’s future was a centralized republic. In this republic, citizens united under a single banner, language and culture, while minorities would be forced to chose between Russianization or deportation.

Pestel’s utopia, inseparable from national identity, resonated with Slavophiles and Orthodox Christians: determinists who, as Riasanovsky and Rubinstein phrase it, believed “Russia’s historical development was unique” and that, “by virtue of their true faith, [the Russian people] had a superior sense of communal responsibility, civic duty justice.” Though the Decembrists were squashed in 1825, Pestel and his chauvinistic ideas survive through the present-day regime of Vladimir Putin.

Vladimir Lenin found solace in the socialist writer Nikolai Chernyshevsky, whose 1963 book What is to be Done? shows how revolutionary heroes, having freed themselves from tradition and superstition, create a society free from economic exploitation. As with the Soviet Union, communism comes at the cost of individual liberties; the socialist way of life is the only way of life, and citizens must rotate jobs to ensure that everyone gets the same work experience.

Lack of agency is not just a common theme in socialist literature, but in theory as well. According to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, history unfolds according to class struggle: a clash of social forces beyond the individual’s control. The inevitable conclusion of this struggle, the duo declares in their Communist Manifesto, is an international uprising that will put an end to global capitalism. The average person has as little say in this process as they do in the governance of Plato’s Republic.

The irrelevance of freedom

Utopian thinkers throughout history were rarely concerned with free will. This is because they spent their lives in search for the answer to life’s biggest questions: the secret to lasting happiness, the administration of perfect justice or — more broadly — the underlying laws of human nature and the universe. They disliked mankind’s independence, which led to chaos and unnecessary bloodshed. Instead, they looked for something — a concept or principle — that could show them the right way.

The Bolsheviks, like Marx, believed the end of capitalism was inevitable. (Credit: A. Sdobnikov / Wikipedia)

Plato’s guide was philosophy – a tool that offered insight into the world of Forms. For St. Augustine, it was the belief in a benevolent and omniscient god. Chernyshevsky, meanwhile, put his faith in the unavoidable demise of capitalism. These thinkers were unconditionally devoted to their ideals. In spite of this, they did not think of themselves as enslaved. Quite the contrary, actually. By serving what they took to be the truth about the world, they believed themselves liberated from falsehoods.

This mindset is illustrated by the Bolshevik Aleksandr Arosev, who wrote in his diary that he was “in awe of the tenacity, durability, and fearlessness of human thought, especially that thought within which—or rather, beneath which—there loomed something larger than thought, something primeval and incomprehensible, something that made it impossible for men not to act in a certain way, not to experience the urge for action so powerful that even death, were it to stand in its way, would appear powerless.”

History, however, seems to have granted victory to Dostoevsky. After all, every attempt at creating a utopia as pictured by humanity’s greatest thinkers has ended in failure. Many were full-blown catastrophes, giving rise to regimes that were far more destructive and disorganized than those they replaced. But while utopian fiction has birthed some real-world dystopias, it has also inspired readers to think creatively about solving social problems of their day — and that’s a valuable thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment