Giangiuseppe Pili and Fabrizio Minniti

Russia’s Zapad military exercises have often been viewed as evidence of the country’s ability to fight at scale. Yet recent developments in Ukraine, where the Russian armed forces have faced significant logistical and operational problems, raise serious questions about Moscow’s preparations to fight a major conflict.

While a variety of factors such as poor political assumptions and corruption in the military have no doubt contributed to Russia’s lacklustre performance, Russia's focus on large-scale operations is only a recent feature of its Zapad exercises. In fact, prior to Zapad 2021, the Russian armed forces had not practiced or undertaken any operations on this scale in the Western Military District since 1981, when between 100,000 and 150,000 troops took part in Zapad 81, the largest military exercise of the Soviet era.

Moreover, even Zapad 2021 – the only recent exercises that match the current invasion in scale – focused on mobile active defence on friendly soil. In other words, the experience and institutional knowledge required to conduct operations at this scale may be more limited across the Russian armed forces than many analysts had previously assumed.

The Russian army has routinely conducted two types of military exercises: annual strategic command staff exercises and combat readiness inspections. Through these drills, Russian forces test military readiness, refine operational concepts, evaluate new equipment and technologies, and improve command-and-control capabilities. The concepts tested and elaborated during these drills reflect how the Russian military plans for upcoming military operations.

Russian strategic command staff exercises take place at the end of the Russian army's annual training cycle, testing large-scale projection and operational capabilities. The exercises usually rotate through Russian military districts: western (Zapad), southern (Kavkaz), central (Tsentr) and eastern (Vostok). Each district hosts an exercise every four years.

Figure 1: Map of Russia’s Military Districts

CreditRUSI

CreditRUSIDuring recent iterations of major exercises, Russia applied new ideas elaborated in Georgia and Syria, and in Ukraine in 2014. But the Russian armed forces only started testing massive mobilisation in the latter part of the last decade, while mobilisation at the scale needed to successfully rehearse the invasion of Ukraine only appears to have started in earnest in 2021. This lack of experience – particularly in the area of logistics and combined arms warfare – may partially explain Russia’s current challenges in the field.

Zapad 2013: Joint Military Exercises with Belarus

In 2013, Russia held joint Zapad exercises with Belarus that sought to integrate lessons learned from the 2008 war in Georgia. The general in charge, Valery Gerasimov, sought to improve interoperability, integration and projectability of the joint armed forces, and considered these the main operational objectives of Zapad 2013. However, the scenario of the exercises was premised on the deterioration of inter-state relations, and the enemy was hypothesised as a number of non-state actor terrorist groups and not a peer adversary.

Several years earlier, the 2008 Georgian war had taught a number of important lessons to the Russian armed forces. As such, Zapad 2013 focused primarily on remedying some of the shortcomings revealed over the course of the war, particularly with respect to delivering effective command and control. During the exercises, the increased efficiency of the chain of command made use of more flexible units with high operational readiness and those more capable of joint operations.

Figure 2: Russian main battle tanks taking part in the Zapad 2013 exercise

Creditkremlin.ru / CC BY 3.0

Creditkremlin.ru / CC BY 3.0Four new commands replaced the six former military districts, while divisions were replaced by lighter and more flexible brigades. The exercise’s declared objective was to address the ‘deterioration of inter-state relations due to inter-ethnic, ethno-religious disputes and territorial claims’. Its primary objective was to improve the operational readiness of the Russian armed forces at the joint level.

From the doctrinal point of view, Zapad 2013 was a stress test for the defence of the combined forces of Belarus and Russia in response to a ‘political-military situation’. Two phases were conducted in each country. The first phase, which lasted one week, concerned the initial Russian and Belarusian reaction to the hostile forces, with the creation of a joint contingent; the second phase was the Russian-Belarusian military operations in response to the crisis. In addition, Belarus tested its ability to mobilise troops for homeland defence.

The exercises of 20–26 September involved all sectors of the Russian armed forces, including air defence, special forces, Ministry of the Interior personnel, logistics and medical support. They also changed the air force command structure in order to improve interoperability between Russian and Belarusian forces. The restructuring of commands led to a redefinition of military districts, mobilising reserves and high-readiness ground forces.

The comprehensive overhaul of command-and-control systems allowed more significant integration of the Belarusian armed forces, enabling the mobilisation and deployment in the theatre of around 40,000 troops (along with the mobilisation of a further 20,000 from the reserves and Ministry of the Interior, in the St Petersburg area). The scenario of the exercise was premised on terrorist groups coming from the Baltic Sea and targeting Belarus. We might assume that ‘terrorists’ in this case was a euphemism for foreign-backed anti-government movements.

The Russian air defence supported the ground forces, while the Baltic Fleet operated a naval interdiction operation to deter the terrorist attack. An urban warfare scenario included the western part of Russia, Belarus, Kaliningrad on the border with Lithuania and Poland, and the Baltic Sea.

Apparently, the exercise considered the deployment of unconventional enemy troops (NATO), which were ‘equalised’ as terrorist groups to be matched by activating units of the Ministry of the Interior. Therefore, integration between counterterrorism units and conventional operations of the armed forces was presumed in the organisation of the exercise and tested. Zapad 2013 was also notable as it involved all branches of the Russian armed forces, with a deployment capability that included Belarusian amphibious troops in large-scale conventional operations that combined joint operations, missile strikes and urban manoeuvres.

Zapad 2013 was limited to a confrontation of ‘Middle Eastern’ numbers in terms of units deployed. Hence, the exercise was intended to be one of limited scale and focused on state-backed unconventional threats to a Russian client. That said, the planners conceived a conventional conflict scenario in tandem with counterterrorism. The number and type of forces differed significantly from the numbers notified to the OSCE (amphibious troops, UAVs for intelligence, monitoring, battle assessment activities, electronic warfare systems, and interceptor fighters for neutralising bombers entering Russian air space).

Though ambitious in terms of its goals regarding cross-service and cross-government integration, Zapad 2013 was limited in scale and did not focus on the sustainment of combat operations. Nevertheless, the exercise represented Russia’s first attempt to put the reforms initiated by former defence minister Anatoly Serdukov (2007–2012) into practice, essentially aiming to professionalise the Russian military through a reduction in the size of units.

Zapad 17: Lessons Learned by Russia in Georgia and Ukraine

Zapad 2017 was the first major Russian exercise after the country’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent hostilities with Ukraine. As such, the exercise occurred within a different political context and during a time of heightened tensions with the West and NATO.

Notably, Russia did not restructure any of its command-and-control chain, while the scenario and actual drills conceived of a conventional war, with massive use of electronic warfare and air defence assets, including anti-access/area denial (A2/AD). Although the exercises involved the air forces and air defence, airborne subunits, Spetsnaz, the Baltic Fleet, and a number of other units, total troop numbers were still compatible with previous international agreements, operating within the constraints of international law.

Figure 3: A Russian T-72B3 taking part in the Zapad 2017 exercise

Creditmil.ru / CC BY 4.0

Creditmil.ru / CC BY 4.0The exercise in 2017 focused on defending Russia against an attack by a number of hypothesised hostile states, and was centred on political pressure imposed by the West, without any major change in Russia’s chain of command and control or military capabilities.

The Veyshnoria exercise scenario covered Belarus’ northwest, not far from the Suwałki gap, a corridor on the Lithuanian-Polish border separating Kaliningrad from Belarus. The area of 12,000 km2 covered the Grodno, Minsk and Vitebsk region, which is where special forces operated and the more tactical part of the drill took place. The location of the exercise near the Suwałki gap may have been a hint that what Russia views as defensive operations could involve limited operationally offensive actions like the seizure of key arteries.

The scenario started with a foreign-sponsored 'hybrid war' attack on Belarus and the Russian Baltic enclave of Kaliningrad by subversive elements supported and supplied by three enemy countries. The exercise involved the air and air defence forces, airborne subunits (represented mostly by the 76th Guards Airborne Division at Pskov), Spetsnaz and the Baltic Fleet, along with the 11th Army Corps by Kaliningrad, subunits of the 6th Army (St Petersburg), and subunits of the 20th Guards Army of Voronezh. According to the commander of the Western Military District, General Andrei Kartapolov, in the Zapad 2017 scenario, the Russian military command utilised lessons learned from its experience in the Syrian civil war.

The scenario and actual drills were conceived for a conventional war, with massive use of electronic warfare and air defence assets. They tested the ability to resist and defend against air and missile attacks on the entire Russian territory, using methodologies already tested in Syria. For instance, A2/AD strategies that the Russian army used in Syria were included. A2/AD was used to create a multi-layered air defence buffer. This was not intended for preparation for a large-scale air attack but for preventively maintaining escalation dominance capability during an escalating conflict. The scale and conduct of the exercise, then, suggested preparation for a rapid fait accompli in a fairly constrained geographical area, utilising a combination of early escalation dominance and subsequent efforts at anti-access to win a quick, limited war – a local war in Russian parlance.

Finally, in comparison with Zapad 2021, Russia still tried to comply with international agreements on military exercises, at least superficially. Indeed, Russia's official notification to the OSCE stated that Zapad 17 involved only 12,700 people – 300 less than the 13,000 or 300 tanks covered by the Vienna Agreement.

Russia's Military Modernisation and Capabilities in Zapad 2021

The drills involved 200,000 military personnel, more than 80 aircraft and helicopters, up to 760 units of military equipment including more than 290 tanks, multiple-launch rocket systems, and 15 ships. The scenario was based on a massive operation and conventional war in response to an allied invasion by three different countries, similar to the Baltic states and Poland. Strategically, the presence of Chinese troops – albeit in small numbers – was clearly of note. At the tactical level, massive numbers of units were deployed in complex joint force operations, meaning that the exercises could be interpreted as the real prelude to the current conflict in Ukraine.

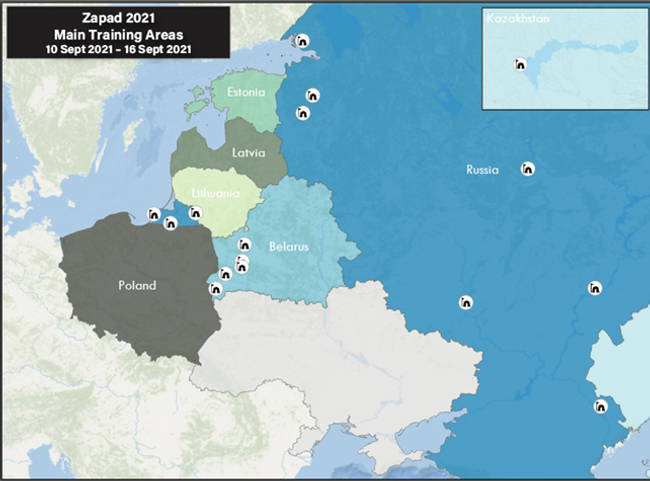

Figure 4: Zapad 2021 main training areas

CreditInstitute for the Study of War / RUSI Project Sandstone

CreditInstitute for the Study of War / RUSI Project SandstoneZapad 2021 was Russia’s first preparation for operations on a scale comparable to those undertaken in Ukraine a year later. Its conduct also underscores Belarus' growing dependence on Russia to deter internal opposition and any possible Western or NATO action. The exercise was conducted in the former Kaliningrad enclave and along the Ukrainian border. In comparison with the other two Zapads, it involved every Russian military district, including southern, northern and central.

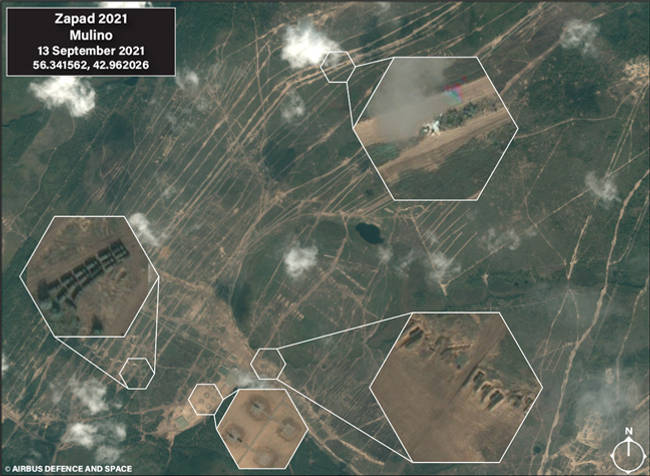

Figure 5: Zapad 2021 at Mulino, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia

CreditAirbus Defence and Space / RUSI

CreditAirbus Defence and Space / RUSIAt the time of Zapad 2017, Western experts estimated that 65–70,000 Russian troops participated, though Russia declared only a fraction of these.

The exercises also coincided with Russia’s abandonment of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe and the Russian withdrawal of the OSCE mission on Ukraine's state border with separatist-controlled regions. Notably, Minsk for the first time characterised the Zapad exercises as part of its strategy against potential NATO aggression.

The Kremlin focused Zapad 2021 on closer integration with the Belarusian army, framing it as a 'joint strategic exercise' with Belarus. With hindsight, this served as the first harbinger of Russia both attempting conflict at scale and attempting to integrate Belarus explicitly into its war planning. Previous exercises hinted at this latter function, though it was framed in terms of counterterrorism – which might have been a cover for attempts to secure the Belarusian regime against internal dissent coupled with external support.

All 'Zapads' have had an active phase of about a week with tactical scenarios of the most significant combat operations, preceded by months of deployments and individual exercises that create the stage for each participating unit to perform its role. However, for the 2021 exercises, the Russian military conducted an unusual number of activities preliminary to and in preparation for the active phase of Zapad, beginning as early as March 2021. Meanwhile, Russia planned the deployment for the active phase for the end of July. In comparison, Russian forces deployed just one week before the active phase in Zapad 2017. In other words, it was not until 2021 that Russia began to truly simulate planning for warfighting at scale.

That said, the scenario planning for Zapad 2021 was still conceived to face a Western coalition consisting of three states that sought to undermine the alliance between Belarus and Russia by force, triggering a regime change in Belarus by occupying its western part. The Western coalition, consisting of Nyaris, Pomorie and the Polar Republic, could be interpreted as representing Lithuania, Latvia and Poland. This coalition was intended to test Russian multi-layer defence by conducting air and missile attacks, crossing the Belarusian border, and penetrating deep into the country. The exercise seemed geared towards operationalising active defence – a strategically defensive but operationally offensive concept based around both mobile and positional defence coupled with area denial and deep strikes. All of these activities were geared towards halting the advance of a superior force and imposing unacceptable costs on the homelands of their adversaries.

In contrast with Zapad 2017, there was no reference to terrorist groups, even in the rhetoric of the mission, as the drills were explicitly conceived for a conventional conflict between the Polar Republic and the Central Federation. The latter has well-employed capabilities of escalation dominance by reacting to massive air offensives, and the enemy penetrated inside Belarusian territory but was halted in its advance by Federation forces.

The Federation forces, supported by airborne infantry, counterattacked the enemy, trying to fragment its penetrated units with conventional and electronic strikes. In the second phase of Zapad 2021, the situation was stabilised with a manoeuvre defence aimed at degrading the forces of the Polar Republic, while the strategic forces attacked the enemy’s critical infrastructure, pushing it to abandon the conflict.

The overall objective was to degrade the adversary's ability and willingness to sustain a long-term military campaign. Consistent with the concept of active defence theorised and put into practice by Gerasimov, the enemy is confronted with decisive, pre-emptive military forces acting as a deterrent. Multi-layered defence, already widely used in Zapad 2017, was again tested using combined ground-to-air operations, close air support and air superiority missions (lessons learnt in the Syrian theatre), along with a rapid deployment of better integrated troops with command-and-control systems.

Zapad 2021 was focused on the mobility of forces on friendly soil, with ground operations combined with lighter paratroopers and amphibious units, while support units made use of electronic warfare, cybernetics and military robotics as part of Gerasimov's active defence concept. The goal of the exercise was to implement the ability to mobilise Russian forces towards a well-defined strategic objective by coordinating with all assets that could potentially be involved.

The need for unity of command meant that the Western Military District had operational control of the troops of the Central Military District, mobilising reservists and security forces. This level of control over large numbers of forces from other military districts, as well as nonmilitary assets and reservists, was a first. In effect, then, it is unclear that Russian district commanders had a great deal of institutional knowledge regarding the coordination of assets on a scale comparable to the Ukraine invasion before this point.

Conclusions from Zapad: Poor Preparation for Ukraine?

It would appear, then, that until recently, Zapad did little to prepare Russia for the logistical and material demands of the war it is currently fighting. The exercises evolved over the last decade from an initial focus on interoperability to the conduct of more localised operations. Meanwhile, the scale of Zapad was fairly limited even up to 2017, and before 2021 commanders of the Western Military District had only limited experience of coordinating large formations from other districts at scale. Only recently have exercises been conducted at a scale comparable to the current conflict.

Despite this, even Zapad 2021 provided poor preparation for a strategic offensive. Its guiding assumption was a defensive political goal – the preservation of a friendly regime. While this involved offensive military actions including deep strikes against enemy homelands and aggressive manoeuvres at the tactical and operational level, many of these were planned in support of a manoeuvre defence on friendly soil. In this context, seemingly inexplicable actions, such as the use of Russian air force assets in risky assaults, might actually have made sense given that the putative scenario would have involved fighting an opponent that was advancing and not defending, and which therefore could not prepare the ground.

In summary, part of the reason that Russia’s supposed preparedness for war at scale has failed to produce results in Ukraine may well be that until very shortly before the war, Russian exercises simply were not geared towards preparations for fighting at scale with the whole of the army. Moreover, the active defence concepts on which the exercises were predicated, while suited to defensive operations, limited wars and faits accompli, were poorly adapted for the large-scale strategic offensive that the Russian armed forces have undertaken in Ukraine, and this may well help to explain their recent performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment