In the early hours of 18 April, Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) launched a military operation inside Northern Iraq dubbed Claw-Lock. Simultaneously, Turkey intensified its military activities in Syria. Furthermore, on 23 May, President Tayyip Erdoğan announced that Turkey will soon start a new military operation in Syria. These moves reflect Turkey’s new military strategy, based on area control, against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). So far, this new approach has yielded military success. However, it is precisely military success that is reinforcing the tendency to deal with the Kurdish problem only in terms of security and military solutions and to rule out any long-term political solution to the problem. Europe should continue to support efforts towards seeking a solution that also addresses the political dimensions of the problem.

Claw-Lock is the latest in a series of cross-border operations by Turkey into Iraqi territory over the last three decades. These operations typically take place in spring, when climate conditions are more beneficial for military moves. Operations in spring also prevent the organisation and regrouping of the militants, who usually spend the winter passively waiting. This year Turkey is simultaneously attacking forces of the People’s Defense Units (YPG) in north-eastern Syria. Turkey’s Kurdish policy does not differentiate between Syria and Iraq, as Turkey considers them to be different theatres of the same struggle. During this struggle over the last years, Turkey has developed a new military approach with two geopolitical aims.

Pushing the Fighting into Syria and Iraq

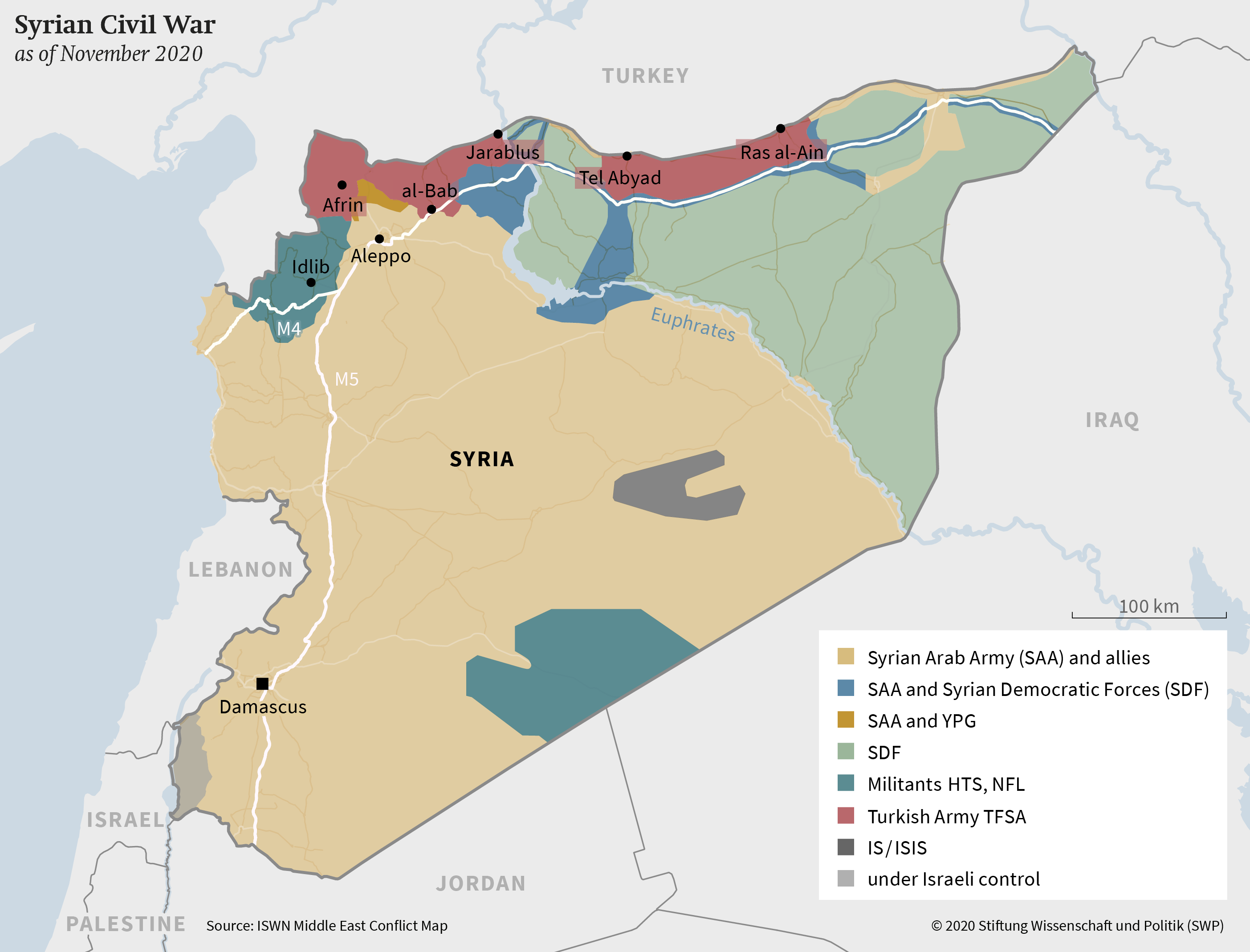

The first aim is to keep the PKK away from the territory of the Republic of Turkey. Instead of chasing PKK militants inside the country, Turkey has gone from being defensive to offensive and now aims to create area control beyond its southern border so as to prevent the massing of PKK forces near its territory. This overall strategy was implemented in different ways in Syria and Iraq. In Syria, Turkey conducted three military operations (in 2016, 2018, and 2019) that specifically aimed to prevent the formation of politically autonomous regions along the Turkish border controlled by the Kurdish-dominated YPG militants.

Table 1

Turkey’s military operations in Syria in comparison

Operation

Region

Start

Euphrates Shield

al-Bab region

24 August 2016

Olive Branch

Afrin region

20 January 2018

Peace Spring

Between Ras al-Ayn and Tel Abyad

9 October 2019

Spring Shield

Idlib region

27 February 2020

A fourth operation in 2020 in the Idlib region did not specifically target PKK affiliates, but it was in line with Turkey’s desire to maintain territorial control and create a buffer zone along the Turkish-Syrian border. As a result of these operations, Turkey is now controlling significant chunks of territory in Northern Syria. Moreover, Turkey has been engaged in state-building attempts in these regions, providing education and healthcare along with security. The Turkish lira is the official currency in these regions, and the administration of the regions is conducted by the governors of Turkish cities on the other side of the border.

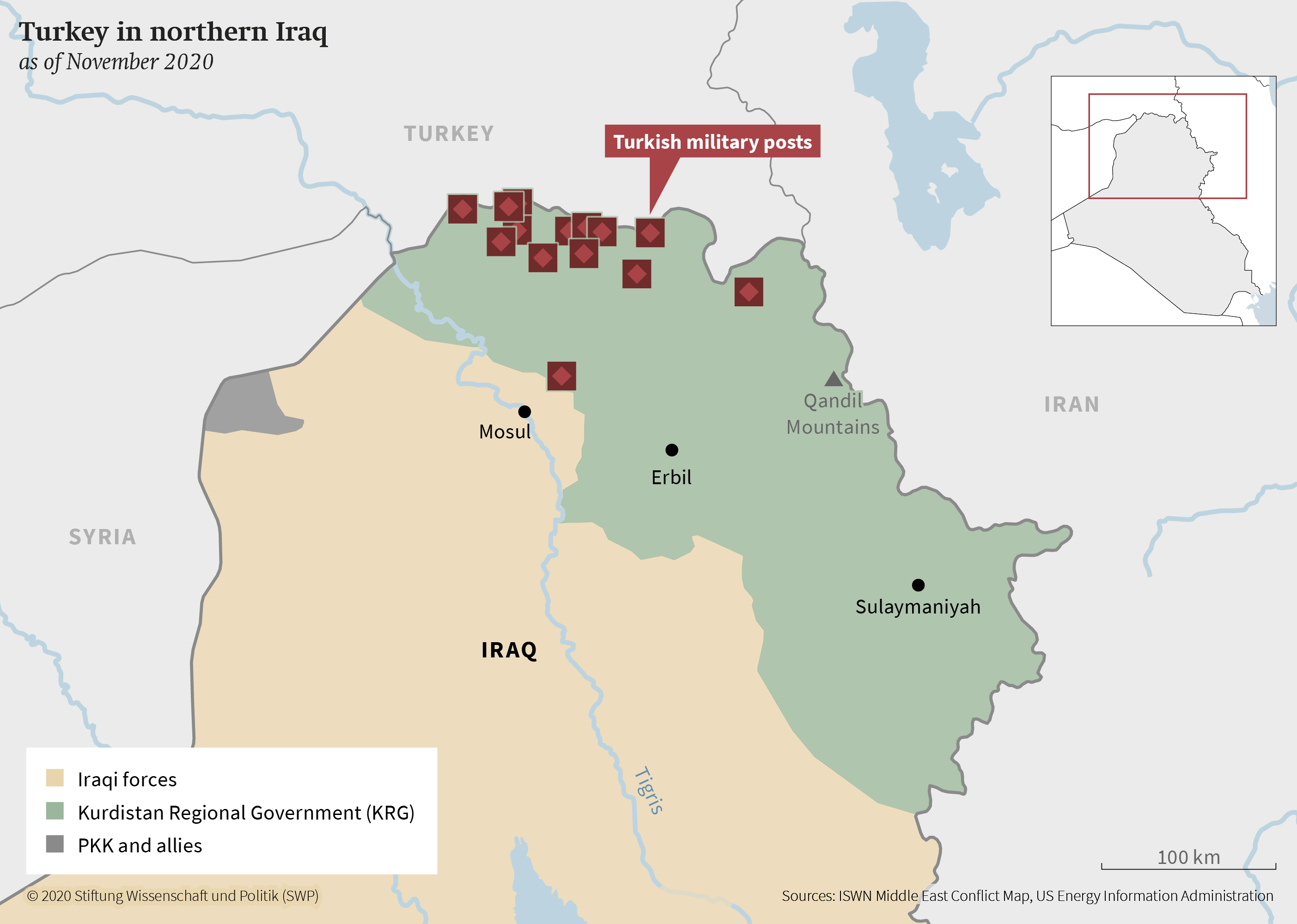

Unlike Syria, where PKK affiliates have never targeted Turkey, Northern Iraq has been the PKK’s launching pad for decades. Thus, Turkey has a long history of cross-border operations inside Iraqi territory that goes back to the 1990s. However, in recent years, the nature of Turkey’s military moves has changed significantly. Previous operations in Iraq were temporary offensives in which Turkey’s air force raided supposed PKK camps in mountainous terrain. Occasionally, air raids were supported by ground troops as well. A couple of permanent Turkish bases in Northern Iraq had been established through informal agreements between Turkey and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), despite a lack of approval and the occasional objection from Baghdad. However, neither these operations nor the limited number of permanent military bases had managed to weaken the PKK’s presence along the Turkish border.

As of 2019, Turkey had changed strategy and started to seek area control with operations named Claw, Claw-Tiger, and Claw-Eagle. Since then, Turkey has maintained a permanent military presence in Northern Iraq that is sustained by a much larger chain of military bases and smaller forward-operation posts along the Iraqi-Turkish border. While numbers are hard to verify, open sources indicate that Turkey has a permanent deployment of 5,000–10,000 soldiers in Iraqi territory.

Unlike in Syria, Turkish area control in Iraq does not amount to the invasion of large territories and the creation of proto state structures. But through these bases, Turkey has created a de facto secure zone and managed to move the armed struggle forward onto Iraqi soil. Turkey is now even building roads in Iraqi territory to connect its military bases in order to achieve more effective area control.

The current Claw-Lock operation is the latest stage of this development. Already its name suggests continuity with the previous operations and the aim to establish long-lasting area control. So, instead of several different military operations, we are witnessing a single, continuous, and long-term military operation interrupted only by winter conditions. The declared aim of Claw-Lock is to maintain area control in the Zap region in the central part of Northern Iraq so as to seal the Iraqi-Turkish border completely.

name suggests continuity with the previous operations and the aim to establish long-lasting area control. So, instead of several different military operations, we are witnessing a single, continuous, and long-term military operation interrupted only by winter conditions. The declared aim of Claw-Lock is to maintain area control in the Zap region in the central part of Northern Iraq so as to seal the Iraqi-Turkish border completely.

Disrupting Logistics and Manoeuvring Capabilities

Map 1

A second aim is to prevent the emergence of a contiguous land corridor controlled in Syria and Iraq by the PKK and its affiliates. Putting it another way, Turkey is prioritising the disruption of logistical connections between various PKK-controlled areas. Turkey’s initial aim was to prevent such a corridor reaching from Iraq to the Mediterranean. The first two operations in Syria managed to push the YPG from the area west of the Euphrates and to confine the territories controlled by the YPG to the east of the river. Later in 2019, Turkey tried to disrupt this land corridor east of the Euphrates with only partial success. Turkish forces captured a thin land corridor between Ras al-Ayn and Tel Abyad. From these corridors and from the Turkish side of the border, Turkey is conducting drone operations and artillery strikes in order to minimise the YPG’s manoeuvrability. Turkey’s military bases in Northern Iraq have also served to limit logistical connections between various PKK camps in Northern Iraq and between the Qandil Mountains, where the PKK headquarters are located.

PKK camps in Northern Iraq and between the Qandil Mountains, where the PKK headquarters are located.

Map 2

Turkey is also aiming to prevent a connection from being established between Iraqi and Syrian territories. To this end, for quite some time now Ankara has been targeting the Sinjar area, which is an important crossing point between Iraq and Syria. The current operation is the culmination of efforts to disrupt the logistical connection between PKK bases in Iraq and SDF-controlled territories in Syria. Two days after its onset, the Iraqi army started its own operation in the Sinjar region against the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS), a Yazidi group closely allied with the PKK. Yazidis are an ethno-religious minority residing mostly in Northern Iraq. Upon the capture of Sinjar in 2014 by the “Islamic State” (IS), Yazidis became the victims of mass persecution, as thousands of Yazidi men were killed and Yazidi women were raped and enslaved by the IS. While the plight of Yazidis led to the emergence of a multinational rescue operation, it was essentially the PKK and YPG fighters who came to the rescue of the Yazidis and managed to open a humanitarian corridor for the evacuation of the besieged Yazidi civilians. Since then, the YBS and the PKK have been closely allied with each other. Ankara has been pushing Baghdad to carry out coordinated operations since 2017 in order to remove PKK and YBS forces out of Sinjar. While Baghdad condemns Turkey’s incursion onto Iraqi soil on paper, it is hard to imagine that these two operations are unrelated.

The Sinjar region is also an important cross-border point for Iran and its “axis of resistance,” which stretches from Iranian territory to Lebanon. Currently, the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), a pro-Iranian militia alliance, is the dominant force in the Sinjar region, and the YBS had been operating under its protection. In recent years, this indirect alliance between the PKK and Iran has become a point of contention between Iran and Turkey. It is possible that Iran and the PMF have also changed their position vis-à-vis the PKK-YBS presence in the region since the PKK’s presence creates the risk of this region being targeted by the TAF. The current operation of Iraqi forces against PKK allies and affiliates appears to be a preemptive move by Iran and Iraq to prevent further Turkish advances on Sinjar.

Outcome of the Operations

This series of military operations has had partial success. Along with the establishment of military bases, they have managed to keep the PKK away from the Turkish border. This can be best measured through the declining number of military conflicts in Turkey. Today, most military conflicts between Turkey’s army and the PKK take place on Iraqi and Syrian soil, pointing to the fact that the main military aim of pushing the PKK away from Turkish territory has been largely successful. Moreover, the use of drones in particular has appeared to be very effective in limiting the PKK’s logistics and manoeuvrability in the region.

Turkey wants to make extensive use of its current technological edge and get decisive military results. However, although these operations have clearly put the PKK in a defensive position and pushed PKK activity further to the south of the Turkish border, they have so far failed to deliver a fatal blow to its fighting capacity.

Moreover, as the fight between the TAF and the PKK moves to Syria and Iraq, Turkey’s Kurdish question becomes more internationalised and draws in other actors. In Syria, despite three military operations and large deployments of Turkey’s military, almost one-third of the Syrian territory still remains under SDF control. While Turkey conducts targeted drone attacks against the SDF high command, it cannot break the SDF’s control in these regions without another massive ground operation. Turkey’s ongoing reconciliation efforts with its Middle Eastern rivals may extend to Syria if both countries manage to agree on a joint operation against SDF forces. According to recent rumours, Turkey is demanding control of the border zone in exchange for political normalisation with the Assad regime. However, it is unlikely that the Syrian regime will accept this in the short run. Until such an agreement is reached between Ankara and Damascus, all Turkish operations in Syria are contingent on, and limited by, approval from the Russians and Americans. Russia is the dominant military force in the Syrian theatre, whereas a small contingent of United States (US) forces is deployed in the region east of the Euphrates under SDF control. On 23 May, Erdoğan announced that Turkey is preparing for a new ground operation in Syria without disclosing the exact locations. This statement should be understood that Ankara sees an opportune moment to expand its territorial control, as it feels that Turkey currently has leverage against Russia and the US.

Most recently Turkey has closed its airspace to Russian planes to and from Syria. This is more about the conflict in Syria than Turkey going along with Western policies against Russia. Through such moves, Turkey is trying to pressure Russia to comply with a new Turkish military operation in Syria. However, for Turkey to be able to target SDF-controlled regions, it also needs the approval of the US. Although Turkey considers Syria and Iraq as different areas of the same struggle, the US consciously makes a distinction between the two arenas. Also, while listing the PKK as a terrorist organisation, the US considers the SDF as its main ally in Syria in the war against ISIS. Therefore, unless the US makes a strategic shift in its Syria policy in general – and particularly in its policy towards the SDF – the complete military eradication of the SDF remains impossible. Most recently, Turkey has declared that it will veto Sweden’s and Finland’s applications for NATO membership on the grounds of the support that these countries give to the YPG/SDF. Although Turkey is publicly accusing Sweden, the real message is being delivered to the US, as Turkey is concerned about the support that the US is giving to the SDF. This strategic difference in approaches vis-à‑vis the SDF so far has been – and will likely remain – one of the biggest obstacles in Turkey-US relations. By announcing the preparations for a new military operation in Syria, Ankara is testing Washington’s commitment to the SDF and trying to use its veto card to push the US to re-evaluate its policy towards the SDF.

The Iraq Front

In Iraq, Turkey so far has had a relatively free hand, as Russia is absent in the region and the US considers Turkey’s military presence to be a counterweight to Iran. However, to get a decisive military victory against the PKK in Iraq, Turkey would need to extend the scope of its operations all the way south to the Qandil Mountains. Such a move has the potential of increasing tensions with Iran. So far, Iran has tolerated Turkish incursions in the north, yet it considers the area further south and the Qandil region to be its own sphere of influence. It is unlikely that Iran would remain passive in the case of a permanent Turkish incursion into Qandil, and it might even decide to support the PKK, leading to renewed and more intense fighting.

Moreover, the PKK’s move further to the south due to Turkey’s area control along the borderline creates new complexities among local actors as well. First of all, as PKK forces move southward, tensions between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the PKK rise, since the KDP sees this as the PKK’s encroachment into territories under its own authority. Moreover, as the PKK moves southward, so do Turkey’s operations and military bases. Additionally, the fight has shifted from the sparsely populated mountainous regions in the immediate south of the Iraqi-Turkish border to more populated settlements, creating a huge security problem for local inhabitants of the KRG.

This is the reason why, in past years, the KRG and the KDP have occasionally condemned Turkish operations in the region. However, over the years the KDP has become increasingly dependent on Turkey for the economic survival of the Kurdistan region. In addition, the alliance with Turkey is important for the KDP to maintain the upper hand toward the Iranian-backed Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Furthermore, the PKK has also become a security challenge for the KDP due to its southward move. This changing power balance between Turkey and the KDP has resulted in the KDP now supporting Turkey’s operations. However, due to local sensibilities and the power of Kurdish nationalism among the population as well as the Peshmerga forces (the official militia of the KRG), KDP support for Turkey remains passive, such as encircling PKK areas and creating logistical obstacles to the PKK’s mobility. However, the KDP purposefully avoids getting involved in military clashes.

Moreover, despite their limited and relatively short-term military success, Turkey’s military operations in Iraq undermine Turkey’s long-term political goals in the country, namely to uphold the territorial integrity of Iraq, and second to maintain its alliance with the KDP. These sometimes conflictual aims are informed by the desire to limit the public appeal of the PKK and Kurdish nationalism in Iraq. However, by freely wandering through Iraqi territory and establishing military bases throughout the entire Northern Iraqi region, Turkey is undermining both Iraq’s territorial integrity and the KDP’s legitimacy among the larger Kurdish population. While the KDP’s popularity declines, the PKK is appearing as the champion of Kurdish nationalism in Northern Iraq and Syria.

The Domestic Dimension of Turkey’s military incursions

While Turkey’s operations follow their own military logic, they are also based on political calculations, as they have significant effects on domestic politics. Here, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) aims to make three gains. First, by further steering the Kurdish conflict, it is trying to create rifts within the opposition. Opposition constituencies in Turkey are quite heterogeneous in their approach to the Kurdish question, and the alliance of opposition parties is trying to maintain a delicate balance between Turkish nationalism and a democratic approach to the Kurdish questions, so as to gain the support of the nationalist / conservative constituencies while not entirely antagonizing the political Kurdish movement. Military operations make this position increasingly untenable.

Second, military operations lead to an increased securitisation of the Kurdish question. This creates a political atmosphere that enables the AKP to criminalise and suppress the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). While the international public knows the case of Selahattin Demirtaş – former co-chair and presidential candidate of the HDP who has been in prison since 2016 – the political oppression against HDP members is massive in scale and includes several MPs, mayors, and a large number of party activists. By the end of 2021, 41 per cent of all party members had been detained at least once in the preceding six months, whereas 17 per cent of all party members were in prison.

So far, the HDP has proven resilient to these pressures, both in terms of party organisation and in terms of popular support. All reliable polls suggest that the HDP maintains approximately 12–13 per cent of the vote. This share is more than sufficient to pass the electoral threshold, which was recently lowered to 7 per cent. Therefore, the AKP will most probably increase the pressure on the HDP to achieve what it has failed to so far: paralyse the party. There is already an ongoing party closure case against the HDP, and one can expect that the oppression conducted against HDP cadres will intensify in the run-up to next years’ elections. Moreover, the continuing securitisation of the Kurdish question and the criminalisation of the HDP are preventing other opposition parties from challenging the AKP’s attempts to paralyse the HDP.

A third political gain for the AKP would be to create a “rally around the flag” effect, as the AKP’s share of votes normally increases 3 to 4 per cent with such military operations. However, these gains are very short-lived, and the polls show that the increase wanes after a month or two. To achieve a sustained political gain, military success on a quite different level is necessary, such as a fatal blow to the PKK’s military capacity or the capture of members of the PKK high command. Achieving this would require extending Turkey’s military control further south in Iraq to include the PKK headquarters in the Qandil Mountains. Given the seasonal timing of the operations in the spring as well as scheduled elections in the summer of 2023, one would expect that next year’s operations will be more sensational and crucial due to domestic electoral calculations. Thus, Claw-Lock can be considered preparation for laying the ground for next year’s more comprehensive military operations.

Conclusion

All in all, Turkey is not using its current military superiority to bring a political solution to the Kurdish question on its borders, but instead considers this as an opportune moment to crush the entire Kurdish political and military movement. Given the regional context that allows Turkey, particularly in Iraq, to move forward with its militaristic approach, and the domestic political climate that favours the AKP’s militarism, it is reasonable to expect the continuation of these operations. However, even though these operations have been successful from a military standpoint, they further complicate the political dimensions of the Kurdish problem. Europe should support a political solution to the Kurdish question that is more stable and long-term. This requires a more regional approach that involves not only Turkey but also its southern neighbours. Therefore, Europe should also focus on the inclusion of Kurdish groups into the reconciliation process in Syria and the rapprochement between Erbil and Baghdad in order to limit Turkish leverage there while continuing to support a de-securitised approach to the Kurdish question within Turkey’s own borders and pushing for a democratic solution to Turkey’s own Kurdish problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment