Mathew Burrows

The war in Ukraine, combined with the lingering effects of the pandemic, means that 2022–23 has become a watershed moment for the growing gap between rich and poor countries. Owing to the increased political instability in many regions, the democratic backsliding that has occurred in Africa, Latin America, and other regions throughout the developing world in recent years is likely to intensify. The stakes are high for the West: China will be the default winner unless Western countries do more to support developing countries. Bearing little responsibility for the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the developing world should not be victimized by it. Nor can the West afford to see its own weakening economic growth prospects exacerbated by the collapse of developing economies.

At least 107 developing countries—home to 1.7 billion people—are now being threatened by at least one of three crises: food, energy, and/or finance. Sixty-nine countries, or 1.2 billion people, are severely affected by all three crises, according to a report by the Deputy United Nations (UN) Secretary-General. The World Bank now predicts that a quarter of a billion people could be pushed into extreme poverty this year—an upwards revision of 77 million—due to the fallout from the war in Ukraine.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization and its World Food Program have also cited the Ukraine war as exacerbating the already steadily rising food crisis with Ukraine unable to export its grain supplies, which account for 12 percent of the planet’s wheat, 15 percent of its corn, and half of its sunflower oil. The Western embargo on Russian oil has stoked market fears about maintaining adequate energy supplies, boosting the global price for energy, even in countries such as the United States, which are not dependent on Russian imports.

The flawed international financial system—which is unprepared for the worsening conditions of the Global South—is greatly in need of reform. The increasing costs borne by the developing countries as a consequence of the sanctions and slowdown in global growth could drive an even deeper wedge between advanced and developing economies than that caused by the pandemic. Without efforts by the Biden administration and other Western governments to assuage their growing plight, developing countries risk becoming more dependent on China, even as Beijing has fewer resources to expend on development assistance due to its own economic slowdown.

A growing debt crisis

Borrowing heavily at low interest rates to handle the health crisis, developing countries are now in the worst possible position while Western central banks raise interest rates, the dollar appreciates at the most rapid rate in years, and inflation is sending the prices of essentials like food and energy beyond easy reach. Sri Lanka recently became the first Asia-Pacific country in decades to default on foreign debt; unfortunately, other developing countries are likely to follow suit.

Having borrowed record amounts to offset the COVID pandemic’s health and social costs, developing countries’ capacity to service their external debt deteriorated during 2020. The external-debt-to-export ratio increased in 121 out of 127 developing countries for which data exist between 2019 and 2020. In 51 countries this indicator stood above 250 percent in 2020, which lies above the risk threshold of 240 percent used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for low-income countries in its Debt Sustainability Framework (DSF). Thirty percent of poorest countries’ debt is at variable rates, increasing the exposure to central bank rate hikes, according to the World Bank. Many developing countries are cutting spending in critical areas such as education, threatening their long-term economic growth.

Countries that appear vulnerable to a sudden crisis, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), due to a combination of large rollover pressures and a large debt-service-to-export ratio include Angola, Egypt, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Three of these—Angola, Egypt, and Pakistan—already have long-term IMF programs in place.

About 104 countries have been net food importers for some time. These countries had a total of $1.4 trillion in external public debt at the end of 2020, and they face $153 billion in projected debt-service payments in 2022, which can be jeopardized if international food prices continue to rise. Some economists warn that the magnitude of food supplied must be on the level of that provided under the Marshall Plan, which saved Western Europe from communism after the Second World War.

So far the Global South has not experienced any significant capital flight, despite signs that monetary policy will tighten substantially this year. Instead of waiting for another “taper tantrum” as happened in 2014 and 2018, the Biden administration and its allied partners should agree on a plan to deal with such an eventuality, which could happen without much warning.

The West should prepare for an extended crisis

The G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative expired at the end of 2021, leaving the Common Framework for Debt Treatment as the main debt-relief instrument despite only three countries having signed up, and none of these has gotten its debt successfully restructured. With the effects of the Ukraine crisis deepening these countries’ fiscal distress, the UN is recommending that the Debt Services Suspension Initiative be extended for at least two years and the Common Framework be dramatically enlarged. A broad range of middle-income emerging and developing economies that are currently ineligible should be considered for the Common Framework. In addition, access limits should be raised for the Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instruments, and those limits should be extended to at least 2024.

Overseas development assistance by advanced countries was at record levels in 2021. Nonetheless, the Ukraine crisis, coming on the heels of the pandemic, is putting an end to the brief economic recovery that many countries saw in 2021–22. The world’s economic prospects would be troubled even without the war in Ukraine and Russian sanctions. Inflation was already a growing worry because of the initial robust pandemic recovery and supply constraints, and with the lockdown spreading in China to counter the Omicron variant in 2021-22, global economic growth was already being downgraded in most forecasts before the Ukraine war.There remains a shortfall of some $15 billion in funding for the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator and the World Health Organization target of vaccinating 70 percent of the world’s poorer populations has still not been met. The pandemic started developing economies on a downward economic path. There is an assumption, because mortality is falling in the United States and Europe, that the threat is waning—but the spread in China and other Asian countries is a reminder that the pandemic has not been conquered. The possibility of more virulent variants appearing in the future poses an ongoing threat for further economic dislocation.

Humanitarian organizations worry that the war in Ukraine will divert too much aid from other urgent needs. Maurice Amollo, a Nigeria-based official with the humanitarian aid group Mercy Corps, praised the “swift” response to the Ukraine crisis and “the generosity in Europe and the United States and beyond.” At the same time, he told Voice of America “we are also getting a little concerned that resources and diplomatic support will inevitably be diverted away from millions of other deserving and vulnerable communities around the world into Ukraine.” For example, Denmark will defer 40-50 percent of its development aid that had been destined for West Africa to boost aid for Ukraine. Sweden—one of the few countries along with Denmark that provides more than 0.7 percent of its GDP in development aid (the UN-recommended level)—has recently announced cuts to its assistance for others due to its funding for Ukrainian refugees.

The appropriation of $58 billion for the baseline international affairs budget by the US Congress is only a 1 percent increase over last year’s appropriation despite growing inflation, and it’s less than both lawmakers and the White House had previously outlined. The bill includes $6.9 billion for the State Department and US Agency for International Development to assist Ukraine, which means reductions for other recipients. Five billion dollars in emergency COVID-19 funding for the rest of the world was stripped out at the last minute. There is a plan to vote on those funds separately later on, but “it’s not clear if there’s enough support to approve them.”

According to the IMF’s April 2022 economic update, “downside risks to the global outlook dominate—including from a possible worsening of the war, escalation of sanctions on Russia, a sharper-than-anticipated deceleration in China as a strict zero-COVID strategy is tested by Omicron . . . moreover, the war in Ukraine has increased the probability of wider social tensions because of higher food and energy prices, which would further weigh on the outlook.” Employment and output for all countries will typically remain below pre-pandemic trends through 2026. “Scarring effects are expected to be much larger in emerging market and developing economies than in advanced economies—reflecting more limited policy support and generally slower vaccination [rates]—with output expected to remain below the pre-pandemic trend through 2026.”

China “wins” out of default?

During the past decades, Chinese influence in the developing world, particularly in Africa and Asia, has grown quickly, making Beijing the most important external partner for many in the Global South. China is the largest trading nation in the world and, as shown by its current slowdown, developments there negatively affect trading partners in Africa and Latin America. How China fares can either lift other countries up or suppress growth elsewhere.

China is the world’s largest official creditor, with outstanding claims in 2017 surpassing the loan books of the IMF, World Bank, and of all other 22 Paris Club governments combined. In recent years, for the 50 most-exposed countries, Germany-based Kiel Institute estimates that debt owed to China has increased from less than 1 percent of debtor country gross domestic product (GDP) in 2005 to more than 15 percent in 2017. A dozen of these countries now owe debt of at least 20 percent of their nominal GDP to China. Most deals are opaque, making it hard to estimate actual amounts of debt owed to China. An estimated fifty percent of China’s lending to developing countries has been assessed to be unreported.

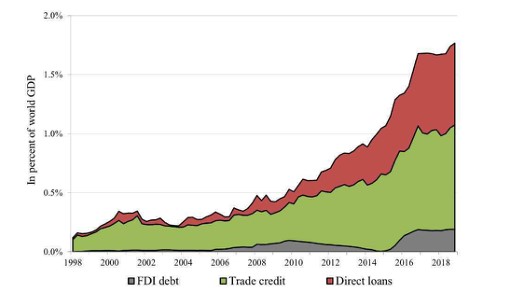

China’s overseas lending boom

The figure represent a subset of outstanding Chinese overseas debt claims as reported in China’s BoP Statistics. Trade credit includes short- and long-term trade credits and advances. Portfolio debt is excluded. From Kiel Institute Working Paper by Horn et al. (2019).

The figure represent a subset of outstanding Chinese overseas debt claims as reported in China’s BoP Statistics. Trade credit includes short- and long-term trade credits and advances. Portfolio debt is excluded. From Kiel Institute Working Paper by Horn et al. (2019).The Kiel Institute judges, however, that China’s lending boom has come to an end, having peaked in 2019. China announced that it had extended debt relief to developing countries worth a combined $2.1 billion under the G20 program—the highest among the group’s members in terms of the amount deferred—but much of the time it provides an extension on repayment. The restructuring and defaults have strongly risen since 2019, according to the Kiel Institute.

Many have criticized Chinese lending as an effort to entice developing states to take on more debt than they can handle and thereby become dependent on China. The London-based Chatham House undertook a comprehensive study of Chinese lending and concluded that “China’s development financing system is too fragmented and poorly coordinated to pursue detailed strategic objectives; and developing-country governments and their associated political and economic interests determine the nature of BRI [Belt-and-Road Initiative] projects on their territory.” The Chatham House study assesses that in the case of Sri Lanka and Malaysia—”the two most widely cited ‘victims’ of China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’”—the debt burdens “arose mainly from the misconduct of local elites and Western-dominated financial markets.”

US options for getting ahead of the unfolding crisis

The United States and other Western countries have an opportunity to demonstrate their concern to debt-ridden developing countries through immediate relief and pushing the G20 to take action over the medium term. Because of the dysfunction within the G20 over Russia’s participation, whether G20 finance ministers will even meet next month in Indonesia is unclear. The United States and other Western countries need to take the lead on their own. After all, it is in the West’s self-interest not to see its own weakening growth prospects further damaged by the collapse of the developing world. The amount of extra money to be distributed by advanced countries from the IMF’s $650 billion allocation of special drawing rights (SDRs) has unfortunately so far fallen short of expectations, after the G20 group of large economies reported combined pledges of $60 billion. According to a Financial Timesreport, “the amount, to be disbursed through the voluntary channeling of special drawing rights, does not match the $100bn set as a ‘global ambition’ by the G20 last year . . . and less than a quarter of the $290bn given to members of the G7 group of advanced economies.” China has pledged a quarter of its SDR allocation to Africa and is playing the role of a provider of liquidity by buying SDRs held by poorer countries. Meanwhile, Republicans in Congress have so far blocked the Biden administration from disbursing the US portion of SDR to poor countries. The administration should try to find ways around Republican opposition.

The United States also has an opportunity to help with lending through the International Development Association (IDA), the concessional lending arm of the World Bank. The United States ”reclaimed its position as IDA’s top donor, pledging $3.5 billion over three years to support pandemic response and an economic rebound in the world’s poorest countries.” Nonetheless, it is up to Congress to deliver on its past commitment and make a partial first installment this year toward the latest US three-year pledge. Donor contributions are a very good value because they typically mobilize four additional dollars in IDA commitments to poor countries. From 2010 to 2020, China went from being IDA’s thirtieth- to its sixth-largest donor. US contributions had been drifting down before this latest commitment.

Debt relief is a harder challenge. David Malpass, World Bank head, has called for a new global cooperative approach and mechanism for providing an early orderly resolution of debt problems and prevent unnecessary defaults. A more permanent solution would mean convincing Beijing to join an internationally agreed-upon mechanism and be transparent about all its lending. Moreover, low- and middle-income countries owe five times as much to commercial creditors as to bilateral ones. The G20’s common framework could be a vehicle so long as there is a common will to use it. Otherwise, creditors will worry it “will just become a covert means of redistribution to other lenders unwilling to play ball.”

It must be recognized that “China has provided more debt relief through the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative than any other country and has bilaterally negotiated up to US $10.8 billion of relief with debtor countries since the onset of the pandemic.” Debtor countries need to assume more responsibility, but the United States and its European allies need to take charge too and not allow a debt crisis, which is already roiling Sri Lanka, to expand and spread, becoming a major challenge for the global financial system. Germany as current G7 president and Indonesia as G20 head have a special responsibility, but the United States should also take a lead, demonstrating its concern for the plight of so many in the developing world.

Stiff costs for all

A “lost” decade for over half of humanity is in no one’s interest. The growing instability in Sri Lanka is a foretaste of what could happen in other countries that are increasingly leveraged and facing rapidly increasing food, energy, and other costs. The Associated Press and National Public Radio have reported that “people have been forced to queue for hours every day to buy essentials. Doctors have warned of a crippling shortage of life-saving drugs in hospitals, and the government has suspended payments on $7 billion in foreign debts due this year alone.” According to the World Bank, “Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has seen a series of massive setbacks to stability in regions across the world: from Asia and Africa to Latin America and the Caribbean and more recently in Eastern Europe.” Even before Russia’s assault on Ukraine produced a record number of refugees, as of mid-year 2021, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that “global forced displacement has likely exceeded 84 million by mid-2021, a sharp increase from the 82.4 million reported at end-2020.” Many went to other developing countries, but a significant number sought refuge in advanced economies.

Scraping by with higher debt servicing and the growing costs of food and energy supplies, developing countries have little to spare for investment in renewables and other climate-change-related mitigations and adaptations, particularly as advanced economies have not met their target of providing $100 billion in annual climate-change support for developing countries.

An opportunity, if not a responsibility

The West’s relatively poor record on getting vaccines out to Africa and elsewhere gave the impression of self-interest. Although the West is by no means responsible for the unprovoked Russian invasion, Ukraine should not be the only target for Western redress. The war in Ukraine may turn out to be an inflection point in more ways than anticipated. The West, which is currently taking care of its own economic problems and ignoring the plight of the developing world, is undermining its influence elsewhere among a majority of the world’s population. In recent years over half of the world’s economic growth has been powered by developing countries, giving others—principally China—an opportunity to expand their influence while undermining democracy prospects in developing nations. Without strong middle classes, democratization will be impeded, and the backsliding that has already occurred will be hard to overcome.

No comments:

Post a Comment