Jyotsna Mehra

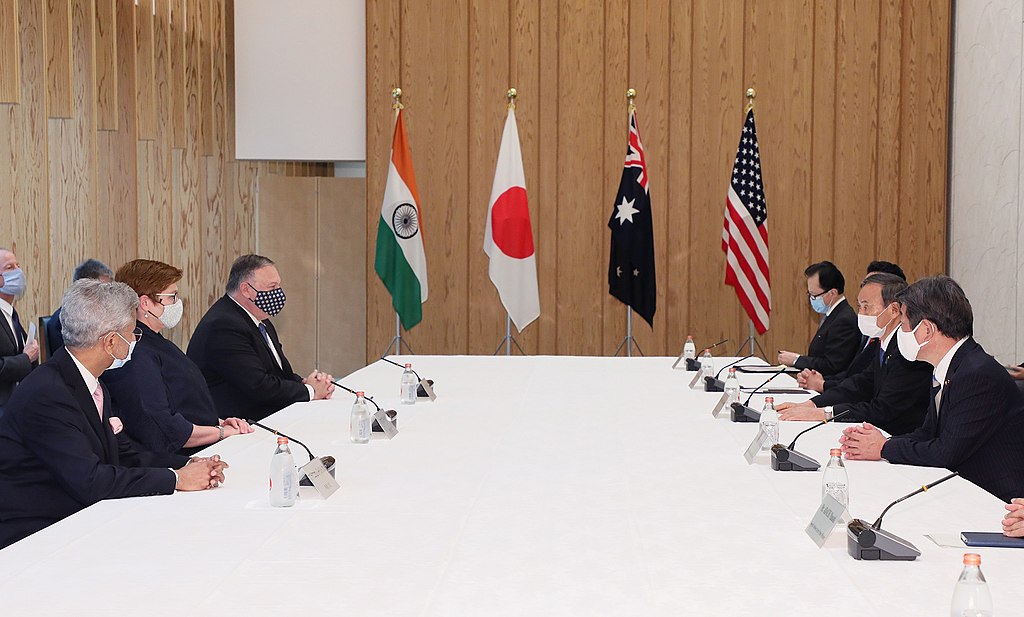

The informal “Quad” group of major Indo-Pacific democracies—Australia, India, Japan and the United States of America (USA)—has been energized in recent years, with virtual summits in March and September 2021 affirming their commitment to the Indo-Pacific region. Nevertheless, the Quad countries are at a critical juncture for articulating the value of the partnership. Quad leaders must develop a robust agenda that delivers meaningful success to justify the Quad as a “force for global good.” Under the three broad themes of pandemic cooperation, emerging technologies, and defense and security, this policy memo identifies initiatives and specific recommendations that can build out this agenda.

The informal “Quad” group of major Indo-Pacific democracies—Australia, India, Japan and the United States of America (USA)—has been energized in recent years, with virtual summits in March and September 2021 affirming their commitment to the Indo-Pacific region. Nevertheless, the Quad countries are at a critical juncture for articulating the value of the partnership. Quad leaders must develop a robust agenda that delivers meaningful success to justify the Quad as a “force for global good.” Under the three broad themes of pandemic cooperation, emerging technologies, and defense and security, this policy memo identifies initiatives and specific recommendations that can build out this agenda.The informal group of major Indo-Pacific democracies, Australia, India, Japan and the United States of America (USA)—the Quad—has received tremendous impetus over the last four years. The Quad Leaders’ virtual meeting, held in March 2021, and the Leaders Summit, held in Washington, DC in September 2021, saw the four countries embrace their partnership, and affirm their commitment to the Indo-Pacific region.1

A key factor that has driven the reemergence of the Quad in recent years has been the four countries’ largely shared outlook on China’s rise in the Indo-Pacific.2 The Quad has repeatedly stressed the importance of the rules-based international order, and freedom of navigation and overflight across the Indo-Pacific—a veiled reference to China’s activities in the region. During the March 2021 Quad Leaders meeting, President Biden and Prime Ministers Modi, Morrison and Suga vowed to establish expert working groups on vaccines, emerging technologies and climate change, paving way for a “formalization” of the partnership. This renewed focus on “soft” security issues raises questions about the role of the re-energized Quad. Some observers worry that this focus on global issues over security concerns vis-a-vis China “would encourage China to step up its coercive diplomacy through heavy-handed use of military and economic power.”3

Since its inception, the Quad has not played an active defense-and-security role with respect to counter-balancing China. With the Quad navies having played a pivotal role in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the roots of the partnership lie in providing vital public goods such as Humanitarian and Disaster Relief Assistance to the region.4 Beijing and some domestic constituencies within Quad countries have portrayed the Quad as a militarized anti-China bloc, or an “Asian NATO.”5 A related concern among Quad states has been that developing the group will jeopardize their bilateral relationships with China. Although the Quad was first formally convened in 2007, these issues have limited the full development of the grouping since then.6

With its grey zone activities across disputed maritime and territorial flashpoints, weaponization of trade, technological advances, and predatory financing across the Indo-Pacific, an increasingly belligerent China is one of the biggest security threats facing each of the four nations. However, there are various ways China can be counterbalanced.7 One of those ways is working on global issues identified during the 2021 Leaders Meetings where—as four democracies that account for about 35 percent of the Global GDP and geographically corner the Indo-Pacific—the Quad vowed to work on functional challenges facing the Indo-Pacific. However, even as the Quad develops structural capacities to deal with these functional challenges, it must not exclude defense and security issues from its purview. As the Indo-Pacific security environment becomes more complex, the Quad countries have been enhancing the interoperability between their militaries.8

Since 2017, the Quad countries have been signaling their renewed interest in working together. However, skeptics of the group have argued that it places “symbolism over substance,” while critics, including Beijing have underplayed its importance, saying that the Quad—like “sea foam”—is set to “dissipate.”9

The Quad countries are at a critical juncture for articulating the value of the partnership. Quad leaders must develop a robust agenda that delivers meaningful success in order to justify the Quad as a “force for global good,” maintain momentum behind its development, deepen cooperation among the Quad countries and strengthen partnerships outside the Quad.10 This policy memo identifies some initiatives that could become a part of this agenda. Under three broad themes of pandemic cooperation, emerging technologies and defense and security, this policy memo lays out specific recommendations for Quad deliverables. As an increasingly aggressive China works towards building a Beijing-led regional order, the Quad could jointly tackle reducing supply chain dependencies on China for critical technologies and pharmaceuticals, comprehensively increasing collaboration to deter security threats presented by emerging technologies, and substantially increasing its capability to monitor maritime Indo-Pacific.

Deliverables

Health Cooperation

The enormity of challenges that accompanied COVID-19 brought pandemic cooperation central to the Quad’s agenda over the last two years. The Quad vaccine experts’ group was formed to implement plans to jointly finance COVID-19 vaccine production in India and supply it to the region.11 The Quad has vowed to deliver at least a billion vaccines globally by the end of 2022.12 However, with ongoing discussions about the “endemic” and the world beginning to “learn to live with COVID-19,” Quad pandemic cooperation will fade into health security cooperation beyond COVID-19.13

Health Cooperation Beyond COVID-19

COVID-19 has illustrated the impetus the governmental agencies of the Quad countries have to coordinate containing future pandemics and sharing regulatory best practices as democracies facing similar pandemic challenges. This could mean that the various national public health agencies, departments of pharmaceuticals, departments of biotechnology maintain regular contact to monitor and share information on emergence of new epidemics and establish an early warning alarm mechanism. In this regard, the Quad’s partnership could partner with bodies such as World Health Organization, Gavi, CEPI, World Health Assembly and UNICEF.

The COVID-19 pandemic has helped the Quad develop “habits of cooperation” which would be useful in managing future global contingencies where the four countries, and their like-minded partners need to quickly convene to discuss a variety of issues. This could include the spread of the virus, the development of variants, lockdowns and repatriation efforts, financing of vaccine research, development and production, supply chains vulnerability and economic recovery.14

Addressing Vulnerabilities in Medical Supply Chains

The Quad countries have made two major announcements on initiatives geared toward supply chain resilience: the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative launched in 2020 by Australia, India and Japan; and an executive order on supply chain resilience signed by President Biden in February 2021. While the Quad has set up a working group on addressing supply chains vulnerabilities in critical technologies, it could also work on identifying vulnerabilities in medical supply chains, especially in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Herein, the Quad could partner with like-minded nations such as Israel, Singapore, UK, France, Germany that have relevant capabilities regarding API manufacturing. This would involve assessing manufacturing capabilities of Quad countries and their partners, drawing financing and investment solutions towards reducing dependencies on China.

Emerging Technologies

During the Leaders’ Summit, the Quad established a working group on emerging technologies, recognizing that the issue of developing, governing, and operating new technologies according to shared values and interests is central to their wider strategic objectives. Implicit in this initiative is the four countries’ concern about China using its tech advancements to directly undermine the security interests of the four countries.

Shaping the Standards Debate

Global technology standards are the crucial benchmark for the development of the technology regime and are fast becoming a tool of exerting global control. Quad Working Group on technology has developed a statement of principles on technology design, development, and use.15 This could form the foundation of a common narrative that the Quad could push at standard-setting organizations, such as International Telecommunications Union (ITU), International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).

Beijing has released “China Standards 2035,” a 15-year blueprint that will lay out its plans to set the global standards for the next-generation of technologies.16 Beijing has been honing its primacy in essentially all three primary standard-setting international organizations—the ISO, the ITU and the IEC. Chinese government officials serve or have recently served across all three as heads. In 2019 alone, China submitted 830 standards proposals to the ITU.17 According to Zhang Xiaogang, former President of the ISO, China had set 495 standards by 2020, even as it had planned to initiate 395, becoming the largest contributor to international standards over the past five years.18 Internationalizing Chinese technical standards is also one of the fundamental aims of the Belt and Road Initiative.19 Chinese advances in technologies such as facial and voice recognition, quantum communications, and the commercial drone market have heightened the urgency to create a framework of standards to govern the development and use of technologies that could be used towards autocratic goals, and to undermine national security of Chinese adversaries.

The Quad could work with partners from the informal Democracy-10 or D-10 group, which is made up of the current G-7 members, plus South Korea, India, and Australia. Although the D-10 is not built solely around the Indo-Pacific construct, technology issues vis-a-vis China are considered critical to its agenda. 20

QTN Track 1.5 Dialogue

The Quad Working Group on Critical and Emerging Technology could establish a Track 1.5 Dialogue with the Quad Tech Network (QTN), an Australian Government initiative to promote research and dialogue on cyber and critical technology issues-currently at Track 2 level. QTN has put up an array of proposals to strengthen Quad cooperation in the tech sector including on cyber security, deployment of beyond 5G technologies, setting up of a multilateral research cloud on Artificial Intelligence and initiatives to close the digital divide in the Indo-Pacific.21 The Dialogue could also involve participation from Quad Fellows, allowing them to work with a wide array professionals from other Quad countries, strengthening linkages between the Quad countries’ scientific communities.22

It would be counter-productive to establish a set agenda for a dynamic space such as technology. This dialogue would play a pivotal role in identifying more areas of cooperation in this sector for the Quad.

Strengthening Partnerships on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Supporting Systems

While the four countries have recently finalized bilateral mechanisms to enhance their AI partnership, there is scope to direct this partnership towards monitoring and countering security threats posed by emerging technologies.23 The Quad could finalize AI-related defense and intelligence cooperation agreements either bilaterally or quadrilaterally—as stand-alone agreements or within the existing security cooperation arrangements.

In addition, Quad could work on building AI systems that do not require large centrally managed data sets by investing in “less than one” or LO-shot learning methods that learn from smaller volumes of data, as well as investing in methods that work on distributed and/or encrypted data that allow greater privacy and are less susceptible to “top down” management.24 This is important because current AI systems that benefit from large data sets that make it easier for authoritarian states such as China with advanced AI capabilities and access to a data on citizens of countries where these technologies are deployed to weaponize it to tighten control at home and carry out influence operations abroad.25

The Quad could also act as a platform for coordinating investment policies towards addressing vulnerabilities in supply chains of critical technologies such as semiconductors, which are critical for developing AI capabilities.26 This may involve working with partners such as Taiwan and South Korea for semiconductors. The Quad could further direct investments towards Rare Earths Elements (REE), which are key for manufacturing semiconductors and many other technologies—and are available in significant reserves in India and Australia.27 China has a monopoly over the production and supply of these elements and has threatened to weaponize their export to target Western companies, including defense manufacturers.28

Defense and Security

Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) in the Indian Ocean has received greater attention over the last few years, with India working on enhancing it in the aftermath of the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks. However, MDA remains critical to manage a wider range of challenges including those that feed into the Quad’s climate objectives such as regulating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. A key challenge among developing nations in the Indo-Pacific has been identified to be the lack of resources and an absence of whole-of national approach towards MDA, resulting in limited MDA.29

Underwater Domain Awareness (UDA) has been even more difficult to achieve, requiring high tech acoustic capabilities, even as there have been increasing underwater threats.30 Acoustic analysis capabilities, critical to enhancing UDA, have remained limited to a small group of countries, including Australia, France, Japan, the United States. India could work within the Quad/Quad Plus arrangements to draw investments and build these capabilities, enhancing UDA in the Indian Ocean Region. Dr. Arzan Tarapore, Research Scholar, Stanford University argues that Anti-Submarine Warfare is one domain where the Quad’s capability “is greater than the sum of its parts,” as a result of the Quad’s advantageous geographic spread, making it easier to track adversary submarines.31 Critical for the security of the sub-surface domain, the Quad has been increasingly focusing on ASW as a part of joint naval drills.32

Beyond this, a wider array of stakeholders including those from national security, blue economy, science and technology and disaster management authorities may be involved to achieve greater interest in/better understanding of the under-sea domain33 Dr. Frank O’ Donnell, Deputy Director of the South Asia Program at Stimson Center suggests that for the Indian Ocean Region, this could be organized around the Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) in Gurugram, India.34 IFC-IOR already hosts liaison officers from the other Quad nations, in addition to those from other partner countries. In addition, as Dr. Satoru Nagao of the Hudson Institute suggests, the Quad countries need to expand their real time maritime information sharing.35 Maritime intelligence sharing among the Quad countries and their partnership through arrangements such as IFC-IOR could focus both on “commercial” white shipping as well as “illegal” dark shipping.

The Quad nations have stated that they will deepen their space cooperation, including exchange of satellite data.36 This could be expanded to leveraging space-based technologies for developing MDA.37

Quad and Friends: Enhancing Interoperability between Forces

Quad participation in the MALABAR exercises is becoming increasingly routinized, just as these drills have become more sophisticated.38 In future, the Quad MALABAR exercise could also include more partners that are playing or seeking to play a more active role in the Indo-Pacific theater as observers: the United Kingdom, Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, France, Bangladesh. Another way the “Quad maritime plus” can be imagined is by facilitating coordination on functional maritime challenges. This would function within a loose Quad Plus framework that focuses on tapping the niche capacities of partners: Japan for economic infrastructure; Australia for fisheries protection; India for securing coastal and littoral areas in IOR, the US for data management and joint operations; and France and Vietnam for their experience in Western Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia, respectively. The Quad countries could also expand their annual slate of other bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral exercises to enhance interoperability between their forces. Jeff Smith, an expert at the Heritage Foundation, suggests that the Quad could consider land and air exercises and invite Quad partners to bilateral exercises of their armies and air force, such as Japan and Australia as observers to US-India Yudh Abhyas.39 To sustain tactical cooperation between their forces, the four must put their logistics agreements to use by allowing access to airfields and bases for refueling, crew rest and confidence building to an extent where, as Dr. Tarapore suggests, the practicing of these agreements itself does not become a “newsworthy” event in its own right.40

Further Recommendations

Recommendations in this section carry a degree of near-term political difficulty in their implementation (for intelligence sharing and climate policy cooperation) and require the establishment of an underlying framework of cooperation, internally and with other partners (for development partnership).

The Quad could consider the creation of a four-way classified information sharing network, that goes beyond maritime intelligence. As Dr. O’ Donnell argues, at the Quad level, the four may decide on a case-by-case basis to share sensitive intelligence within the group.41 Further, Dr. Nagao argues that China has been responding to changes in military balance in Asia [French withdrawal from Indo China, U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S. withdrawal from the Philippines] to expand territorially into South China Sea. Therefore, he argues, the Quad must not allow a power vacuum to exist in Indo-Pacific, and it must work to maintain a military balance in the region.42

Even though the Quad has established a Climate Working Group, climate would be a particularly difficult theme to jointly work on, considering differing climate policies and ambitions.43 It may be easier to approach climate objectives as a part of a wider agenda that includes emerging technologies and defense and security. As iterated above, enhancing MDA would help the Quad regulate IUU fishing. The Quad could work with Indian Ocean Island nations and the Pacific Island countries on blue economy and climate technology initiatives by considering extending credit lines for specific projects.On the development partnership, Quad members could explore how they can work on different parts of infrastructure projects, overcoming limitations of varied sets of regulations. India could consider joining the Blue Dot Network, a certification mechanism for quality infrastructure, which under the Trump administration, the United States, Australia, and Japan joined.44

Conclusion

The wisdom in seeking close cooperation with like-minded democracies in responding to the enormity of global challenges posed by COVID-19 has brought these transnational issues to the Quad agenda. It is also guided by a change in administration in the United States wherein the focus on what could be seen as “Democrat agenda items” has allowed President Biden to divorce the Quad from perceptions of it being an “anti-China club,” making it more palatable to President Biden’s voter base.45 This has also made it easier for countries such as India and Japan to embrace the group more openly.

However, as this policy memo illustrates, the expansion into global issues is not zero sum: there remains a widening scope for the Quad to cooperate on defense and security issues in the Indo-Pacific. Concerns about China fundamentally drive Quad cooperation across several areas-from technology to maritime security, connectivity to development partnership even if they are packaged differently.

The expansion into addressing global issues and functional challenges discussed in this policy memo would allow the Quad to develop an agenda— the lack of which has previously limited the robustness of the partnership.46 As this agenda develops, the Quad partnership can become more broad-based, moving beyond foreign ministries towards a “whole of government approach” with defense and home ministries facilitating cooperation on information sharing, counter terrorism, cyber security, and trade ministries working on supply chains.47

Importantly, a flexible agenda would allow the Quad countries to develop greater familiarity and “habits of cooperation.” Sustained partnership around this evolving agenda would keep pushing the boundaries of what is politically acceptable for the Quad to work on collaboratively. This increasingly level of familiarity will be critical when the four decide to work together in face of an emergency that threatens security and stability in the Indo-Pacific.48

No comments:

Post a Comment