AADIL BRAR

In the past weeks, visuals of police and health workers in Shanghai forcing themselves into people’s homes and spraying massive quantities of disinfectant captured headlines worldwide. But what justifies China’s authority over people’s personal space under Xi Jinping? Han Fei, an ancient Chinese political philosopher, may have some answers to offer.

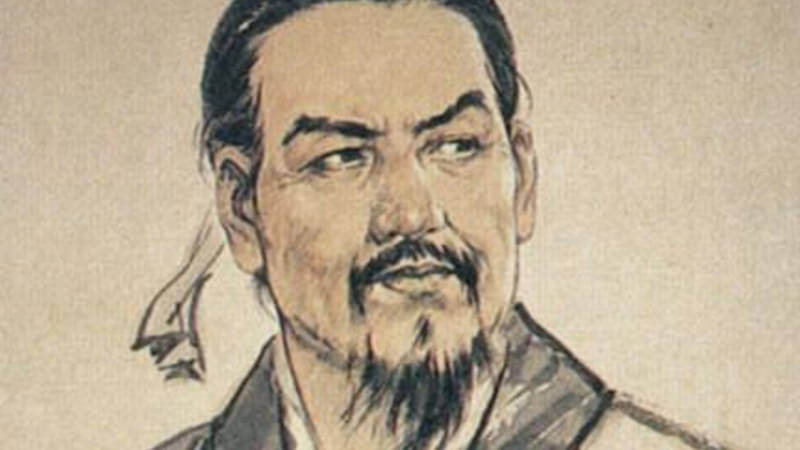

Confucius and Sun Tzu are probably the most well-known Chinese political philosophers outside China. But the philosopher who has grown very popular lately among elite Chinese politicians is Han Fei. Sometimes referred to as China’s Machiavelli, Han Fei—of Korean origin—was a prince of the ruling family of Han and is known to have lived during the Warring States period.

The books that leaders read impact their governance style—leaving a long shadow. And Xi Jinping regularly quotes from Han Fei.

“When the law changes with the times, it is governed well, and when the law and the world are appropriate, there is merit,” Xi Jinping said quoting Han Fei on the need for legislation to keep up with time.

Even Mao Zedong admired Han Fei’s ideology. “What Han Fei meant by ‘force and strength’ was power,” Mao said about Han Fei’s work, concluding, “A smart emperor must control power.”

Punishment and reward

The Warring States period from 475–221 BC was a brutal phase of Chinese history when small kingdoms were fighting amongst each other for supremacy. But the period saw the origins of philosophical traditions, including Confucius thinkers such as Mencius and Xunzi. The rich history of this period laid the foundation for governmental structures and philosophical traditions that define the relationship between people and the State to this day.

Han Fei is attributed as one of the founders of the ‘legalist school’ of Chinese philosophy. Han Fei’s ‘Defining the Standards’ (Ding fa) is the primary text of the legalist school. Han Fei takes a materialist and a realist view of politics, which he supports with a maximalist legalistic action to shore up a sovereign’s authority. Other philosophers of the legalist school are Shang Yang and Shen Buhai, but Han Fei has emerged as the modern-day face of the legalist school.

Unlike Confucius, whose philosophy prescribes a patriarchal morality at a more personal level, Han Fei is more concerned with macro legalism that he forwards as the basis of the State’s authority. The core tenant of Han Fei’s philosophy is the legalistic adherence to agriculture and war, which requires a militaristic fervour to maintain the State’s power. Han Fei promoted a system of rewards and punishment by the State to govern the people. He suggests using the harshest punishment for minor infringements to condition the subjects of a State and stop them from breaking the law.

“Therefore, an enlightened ruler will make use of men’s strength but will not heed their words, will reward their accomplishments but will prohibit useless activities. Then the people will be willing to exert themselves to the point of death in the service of their sovereign,” Christopher Rand quotes from the original text of Han Feizi.

The Warring States period was marked by new militarism defining the legalist school’s preoccupation with harsh punishment and some rewards. These ideas underlying the philosophy would return at different periods of Chinese history.

Collective morality in China

Han Fei’s philosophy had a profound impact on emperor Qin Shi Huang, the leader who finally united the small states (approx. 221 BCE) into the kingdom of Qin – known as the Qin dynasty. Qin Shi Huang even adopted the legalist governance model by issuing maximum punishments to alleged criminals for petty violations.

But Han Fei wasn’t entirely devoid of morality in the political context. He argued for collective morality by the State power, which works for the ‘good of the subjects’.

“Hanfeizi believes that human beings are selfish; hence, conflict cannot be eliminated, and only if a state is strong can it uphold state interests,” Yan Xuetong summarises Han Fei’s views.

One of the modern-day applications of the legalist philosophy in China is the Social Credit System (SCS). The SCS has an in-built system of rewards and punishment to nudge people into following a collective morality in different sectors of society.

“As with the legalist ideal, these schemes do not apply a single behavioural code to every area of society. Rather, there are sector-specific criteria. There are different rules, rewards, and punishments for the healthcare sector, heavy industry, tourism, business, and education. This mirrors the ancient system of ‘names and tallies’,” Samuel Parsons writes about underlying legalist philosophy in the Social Credit System.

Legalism began to fall out of favour under Emperor Wu of Han between (141–87 BCE) as the philosophy came under criticism for its excessive harshness and oppression of the people.

Han Fei’s end was tragic. Han is said to have been poisoned while in custody King of Qin, and some experts speculate his poisoning was approved by the king – the same person Han wanted to serve.

Why Xi quotes Han

The legalist school of philosophy has been used to justify a more hierarchical control of the Chinese Communist Party. When Xi was consolidating his rule in 2014, he quoted Han Fei several times to justify his power consolidation campaign.

“No country is permanently strong, nor is any country permanently weak. If those who impose The Law ding fǎ are strong, the country will be strong; if they are weak, the country will be weak,” Xi’s top quote from Han Fei reads.

The gilded age of wealth accumulation under Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao (1989 to 2013) witnessed the rise of a new entrepreneurial class that considered itself above the law. Xi views his rise as part of a course correction by reenforcing the State’s authority through the legalist school of governance – and in the process, justifying his policies.

Xu Zhangrun, a law professor who was detained in 2020, has reflected on Han Fei and the legalist school’s influence on Xi’s governance style. “An evolving form of military tyranny that is underpinned by an ideology that I call ‘Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism’, one that is cobbled together from strains of traditional harsh Chinese Legalist thought,” Xu wrote about Xi’s handling of the Covid pandemic.

The tension between a people-centric approach to governance and a legalistic control, flows through Chinese history. The kicking and screaming of local residents during the Shanghai lockdown have reminded Chinese people about the legalist excesses of the State.

No comments:

Post a Comment